In art, while most seated Buddhas are always seen as healthy, happy, and peaceful looking, a number of rare sculptures focus on illustrating the realities that wore down his body. These rare statues portray an event that took place before the Buddha’s enlightenment. Through comparing and contrasting three images of Emaciated Buddha from different contexts, this post will explore the meaning and history of Emaciated Buddha and fasting in Buddhism.

One of the oldest religions, Buddhism, was founded approximately 2,000 years ago. The earliest Buddhist sculpture was created according to the tenets of aniconism in North India dating back to the 1st century BCE. Buddha was not represented in human form but was implied through symbols such as footprints or an empty seat.

The sculptures of Buddha were not created until 400-500 years following the death of Guatama Buddha, who was Prince Siddhartha. Siddhartha led a privileged and wealthy early life. One day when he was hunting, he saw a sick man, an aged man, and then a funeral with many people crying. Moved by all the things he had experienced, the prince left the palace and became a beggar in order to search for enlightenment. In the pursuit of enlightenment, Buddha sat beneath the bodhi tree for seven weeks. Nearly dying from hunger, a young girl offered him a bowl of rice and milk. Buddha realized in this time that fasting and asceticism can not bring him enlightenment and therefore he abandoned the harsh practices for good. He came to view asceticism as an extreme and equally false path as that of the privilege and luxury which he had abandoned. He understood that mental cultivation and insight, not bodily deprivation, would lead to enlightenment. This is a significant moment in the history of Buddhism and one which many artists strive to capture.

Unlike other religions trying to avoid idolism, for example Islam and the iconoclastic variants of Christianity, it is common in Buddhism to make sculptures that are used in religious practice. For Buddhists, Buddha sculptures serve as visual imagery intended to narrate the various aspects of the Buddha’s life and lessons. This practice is somewhat similar to the use of icons in the Orthodox Christian churches.

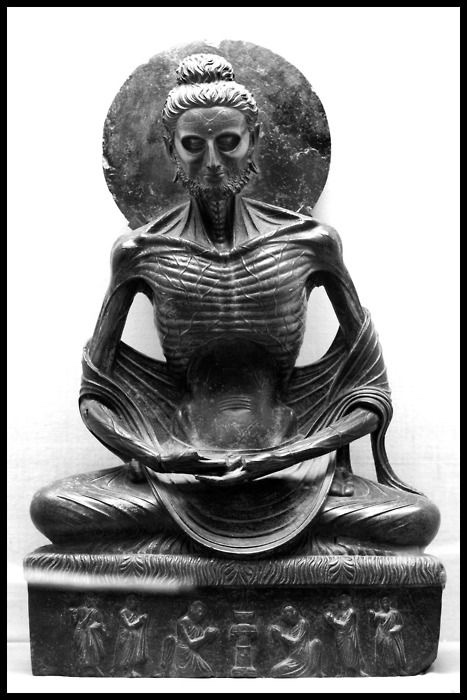

There are three emaciated Buddha sculptures particularly I would like to discuss, all of which belong to contemporaneous Gandhara art and its traditions, located in modern-day northern Pakistan and parts of eastern Afghanistan: the Schist head of the fasting Buddha from 2nd-3rd century; the Fasting Siddhartha from 2nd century; and Fasting Buddha Shakyamuni from 3rd-5th century. These sculptures include the body of a fasting Buddha seated in meditation poses without head, the head portion of Buddha without body, and the whole body of the Emaciated Buddha. After comparing and contextualizing three sculptures, we could indicate that the ancient Indian artists of the Gandhara region had some basic knowledge of human anatomy, which moreover resulted in a heightened realism in anatomical depiction. These early sculptures created a standard for iconic language, leading all the other emaciated buddhas to appear more naturalistically starved. The sculptures have shown that the artists had knowledge of the size and bones’ positions, and muscles of each part of the body. Additionally, they also seemed to have a basic idea about the physiological changes that occur during starvation, such as shown bones, skinny neck, and the thin stomach. These characteristics all showed the weakness of the buddha. Additionally, when images of Buddha began to emerge around the first century CE in India, artists were greatly influenced by Roman statues. Therefore, the subjects of these sculptures tend to have European physiognomies. As a result, in the 1970s, these sculptures were criticized by many experts for falling under the influence of Orientalism. The sculpture of Schist head of the fasting Buddha appeared reminiscent of Apollo, such as his youthful hair arranged in waves, and the look of his face.

These Fasting Buddha sculptures remind Buddhists how much Buddha went through to become fully enlightened. In popular East Asian culture, most depictions of Buddha focus on the contentment that comes from enlightenment, such as the smiling pot-bellied Buddha. Nothing is shown of his plight. However, Fasting Buddha focuses on the journey toward enlightenment. Since Buddhism is about self-perfection, this moment is important for showing how a difficult process is necessary for the desired result. The viewer thus has something with which to engage; the imperfect images are implying a difficult spiritual and physical journey. Like depictions of Jesus Christ’s suffering on the cross, the Emaciated Buddha evokes ideas of suffering and transcendence.

References

https://www.dawn.com/news/1115168

https://artsandculture.google.com/asset/_/QgGcgQazjovxxg

https://www.britishmuseum.org/collection/object/A_1907-1228-1

https://telanganatoday.com/century-old-idol-wastes-away-in-lahore-museum