Finn Boed and Spencer Crough

http://diluo.digital.conncoll.edu/Asianart/uncategorized/i-ghosts/

http://diluo.digital.conncoll.edu/Asianart/uncategorized/water/

http://diluo.digital.conncoll.edu/Asianart/uncategorized/vi-atomic-desert/

http://diluo.digital.conncoll.edu/Asianart/uncategorized/ix-yaizu/

http://diluo.digital.conncoll.edu/Asianart/uncategorized/xi-mother-and-child/

http://diluo.digital.conncoll.edu/Asianart/uncategorized/xii-floating-lanterns/

http://diluo.digital.conncoll.edu/Asianart/uncategorized/death-of-the-american-prisoners-of-war/

http://diluo.digital.conncoll.edu/Asianart/uncategorized/xiv-crows/

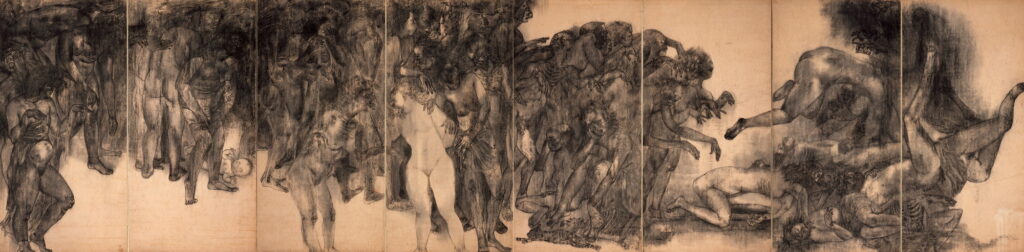

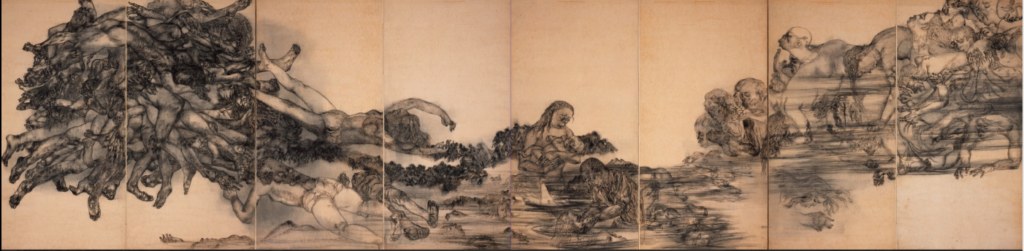

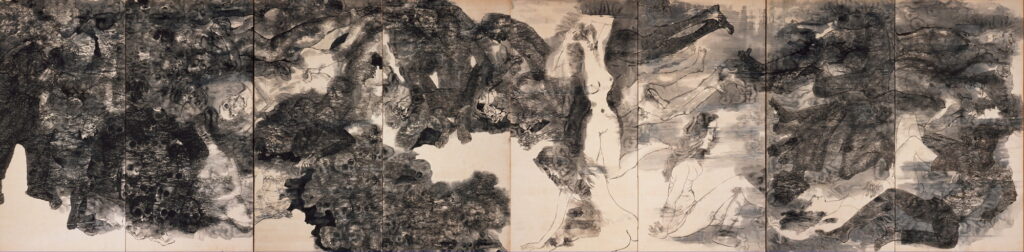

“The Hiroshima Panels” are in the context of the years-long aftermath following the atomic bombing of Hiroshima, Japan. Ensuing the deadliest conflict in human history, World War II, the United States decided to drop a newly created weapon, the atomic bomb, on Hiroshima on August 6th, 1945. The justification for the first-ever use of a nuclear weapon in war was that it shortened the conflict, and thus saving lives. Nevertheless, atomic bombs are not targeted weapons, and their impact is vast. The entire city was vaporized almost instantaneously, as over 100,000 people perished then, and have continued to perish since – due to the long-lasting effects of nuclear radiation. This necessary context sets the scene for the panels, which display sheer horror and misery, with little hope to be seen. The two artists, Iri and Toshi Maruki lost several family members in the bombing and experienced the death that consumed the entire city.

In our presentation, The Hiroshima Panels and Post Atomic Bomb Art in Japan, our goal is to delve into the historical and academic matter in a way that shows the audience a side of the event that most Americans have not experienced. The panels display the horror of the atomic bomb in such dark detail that it is impossible to ignore the consequences of the decision to drop the bomb. We believe that this is crucial in conveying the message to the class that the decision to drop the bomb in World War II did not only scar Hiroshima- it left a scar on humanity itself. As Americans, we have grown up largely shielded from the horror that our country caused and these paintings portray our own doing with a style that forces the audience to temporarily forget the context of the bombing, and to just witness in the moment the sheer misery that humans experienced.

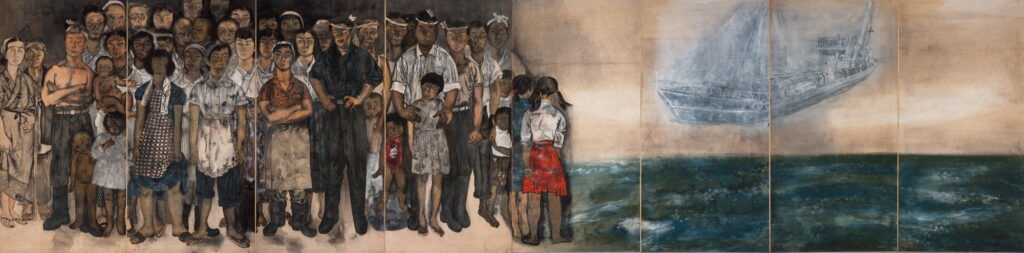

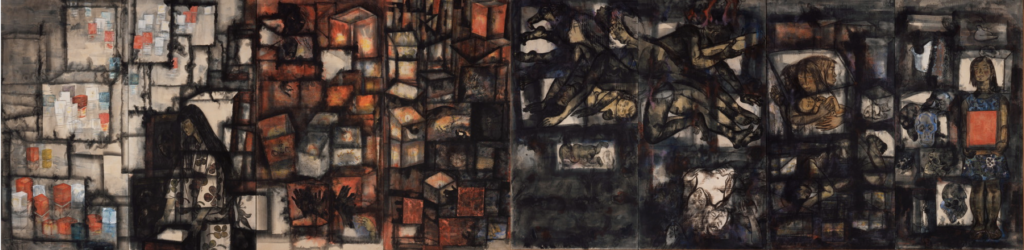

The panels we selected for this exhibit visually and thematically portray “The Hiroshima Panels” in their entirety – capturing the essence of the entire group of panels. In addition, specific panels we chose, such as Yaizu and Death of the American Prisoners of War, depict stories that are equally as appalling, but largely untold. Not only did these panels speak to the impact of atomic bombs on the Japanese people (largely innocent civilians), but how Americans and Micronesians were unwittingly exposed to the bomb, though they were not targeted specifically.

The panels challenge the notion that the atomic bombs saved lives as they show the audience that in a uniquely cruel way, they destroyed much more than a city. In the process, the atomic bomb revealed the darkest depths of human potential, while reducing innocent civilians to clamor for the most basic goods necessary for survival, such as water – the name of the third panel. In addition, a key theme of the panels is that the atomic bomb stripped people of their humanity. As a weapon with such a vast immediate impact, and such a long-term potential for lingering death, the atomic bomb did not discriminate between its victims. Civilians and soldiers, Japanese and Americans, and men, women and children were killed alike. Denied their most basic humanity, the panels largely display piles of humans both dead and alive, as the black ink and charcoal on the panels blur the individuality of each person present. It is impossible to tell who is who, and whether or not they had any involvement in the actual war. Thus, the panels challenge the America-centric notions surrounding the atomic bombing of Japan during World War II.

The visual presentation of the panels is deliberate and important to the viewing experience. The panels are 1.8 meters tall and 7.2 meters long so the viewer is completely immersed in these almost life-sized depictions. They are done on traditional byōbu screens that fold out, so, “tragedy literally unfolds before viewers” (Voon). Visual analysis also plays a role in identifying trends we see throughout the paintings. The panels were created from 1950 through the 1970s. The panels from the 1950s and 1970s are similar in their use of charcoal and sumi ink to create very dark and blurry paintings (the meaning of which is described above), whereas the paintings from the 1960s are more abstract and colorful, with geometric patterns such as repeated squares visible – a stark contrast from the style in the 1950s and 1970s. However, more academic research on this subject would further our understanding of why this arc exists in “The Hiroshima Panels”.

Annotated Bibliography

Maruki, Iri, and Toshi Maruki. “The Hiroshima Panels: Maruki Gallery For The Hiroshima Panels.” 原爆の図 丸木美術館 | Maruki Gallery For The Hiroshima Panels, 3 May 2020, marukigallery.jp/en/hiroshimapanels/.

Voon, Claire. “The Historic Painted Panels That Exposed the Hell of Hiroshima.” Hyperallergic, 6 Dec. 2015, hyperallergic.com/255344/the-historic-painted-panels-that-exposed-the-hell-of-hiroshima/.