Wesoly Hanger – AHI 205

My goal in the exhibition and analysis of these artworks is to showcase the simple, aesthetic beauty in the pieces, to dive into the background of the artists, and further, to provide an argument as to what philosophy and mindset these artistic aesthetics and values derive from. I have brought together these five pieces from four different creators in order to highlight the differences, similarities, and inspirations among the works. I chose to include this amount of works in hopes of putting together a comprehensive and strong analysis of Zen Buddhist landscape art. These three chosen artists followed the school of Japanese Zen, a form of Buddhism. The Zen Buddhists were heavily devoted individuals who focused on meditation and enlightenment. The production of the artwork on display served as a form of meditation and inward contemplation for the Zen Buddhist artist, rather than being artwork with the purpose of being displayed and shown to the public (this is why the dates of the paintings are often ambiguous.) In visual analysis of these landscapes the viewer will find simple, natural subjects such as a tree amongst limited human civilization, heavy contrast between foreground and background, and often large portions of empty, blank space. The subjects and features of the paintings produce emotions in the viewer such as solitude, contemplation, and even aloneness, which can be attributed to the artists ability to express their inner values through a paint brush and ink. The first artist whose work is displayed in the exhibition is Toyo Sesshu, who is certainly the most historically influential of the group. Sesshu popularized the Haboku style of painting, which required a clear mind, and meditative strokes that claimed to capture the true metaphysical nature of the subject. During a time of social advancement in Japan, and as populations directed towards urban centers, some Zen Buddhists found fulfillment and enlightenment in the rustic lifestyle of solitude, and it is through these meditative paintings that we see these values and pleasures of life come through. I chose to exhibit these 5 images in specific because I believe they strongly relate to this point on the true metaphysical essence, and struck in me the greatest sensations that I have highlighted. In my research of the Zen Buddhists, the background of the paintings, and the general philosophies and values in Japanese culture, I came across the terms wabi and Sabi which I thought accurately encapsulated a lot of these feelings I had when analyzing the Zen Buddhist landscapes. A passage from the book Dancing Into Darkness: Butoh, Zen, and Japan explains it as ” Wabi (elemental grace, rustic and ascetic) and Sabi (objective, understated dignity and the delicate traces of time) infuse Zen.” To me, these terms are easily paired with the exhibited photos given the values and artists that they derive from. I argue that there is a heavy connection between this aesthetic concept of solitude; graceful aging; and the ever moving and delicate essence of the universe, and the scenic and contemplative landscape paintings created by these thoughtful men.

1) “Hatsuboku Landscape” by Toyo Sesshu

- 1495, Muromachi period

- 58.3 In. height, 12.9 in. width

- Located in the Tokyo National Museum in Tokyo, Japan.

- https://library.artstor.org/#/asset/HUNT_56443

“Hatsuboku Landscape,” the most famous of Sesshu’s works, establishes the monochrome ink painting style of Haboku which would become a signature style of Japanese Zen Buddhist artwork. This painting features a simple tree as the main subject, whereas more traditional Zen Buddhist painters favored religious figures or symbols as the main subject rather than more secular, natural objects like we see here. The “splashed ink” technique shows in the abstract depiction of the tree; Sesshu used this technique with a clear mind and the creation of this work served as a meditation for him, and an artistic method of grasping the true essence of nature. The subtle but ominous mountainous figures in the background provide an important contrast to the bold and sharp lines of the tree. The touches in the background also allow a feeling of completeness in the painting, and justifies the abundance of blank space around the border of the piece. The aloneness and simplicity of the tree subject inspires in the viewer feelings of solitude, clarity, and inner peace, a sensation that is consistent with the philosophy and lifestyle of the Zen Buddhist Sesshu.

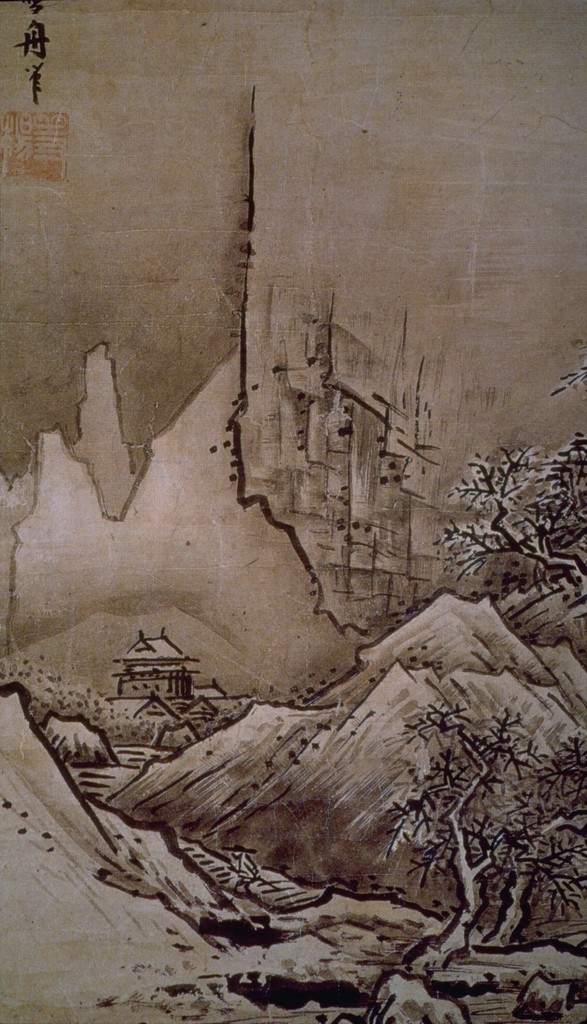

2) “Winter Landscape” by Toyo Sesshu

- ca. 1470 – 1480, Muromachi Period

- 18.3 in. height, 11.6 in. width

- Located in the Tokyo National Museum in Tokyo, Japan.

- https://library.artstor.org/#/asset/AIC_760024

This painting by Sesshu displays a cold and dark winter landscape. Similar to the first painting, Sesshu incorporates intentional ambiguity by leaving out detail in the blank sections of the mountains and sky, and rather paints abstract lines that mimic the form of the natural scenery. However Sesshu provides much more detail in the foreground and middle ground of this painting. On the left side, we see a lone human who seems to be traveling through the vast and cold landscape towards his lonesome abode in the mountains. This detail of human life inspires the philosophical thoughts of solitude, and appeals to the rustic and aged aesthetic or lifestyle that Sesshu and other Zen Buddhists value. In one’s isolation in this expansive scene of nature, there is space and time for meditation, self reflection which are said to lead to an understanding of one’s place and meaning in the universe.

3) Untitled Landscape by Tensho Shubun

- 15th century, Muromachi period.

- Data collected from UCSD

- https://library.artstor.org/#/asset/ARTSTOR_103_41822000270775

This painting by Zen Buddhist Shubun stands out in its lack of detail in the mid ground. The presence of human life with the solitary cabin in the woods balances out the towering natural scenery in the background. Like the “Hatsuboku Landscape” this painting allows an abundance of empty space while still retaining a feeling of completion. Nevertheless, the eyes are drawn to the small cabin, the only evidence of human civilization, which is likely where the artist spends his time meditating. Bold, monochrome lines draw the subject out from the atmospheric ambiguity of the middle ground, and ultimately create a well balanced image which appeals to the rustic and isolated lifestyle of the Zen Buddhist.

4) “Returning Home” by Kenko Shokei

- Mid 1500s, Muromachi Period.

- 65 in. height, 22 in. width.

- Located in the Cleveland Museum of Art in Cleveland, Ohio.

- https://library.artstor.org/#/asset/24628527

This painting by Shubun illustrates the theme of solitude and the rustic lifestyle that is valued by the Zen Buddhists. In the foreground we see a massive boulder, to which clings a tall, angling tree that provides a canopy over the small cabin. This is another painting that most likely depicts the humble abode of the artist, while also including the vast natural environment of mountains, valleys, and forest that encompass it. If you look closely, the viewer can spot two human figures who seem to be pulling a boat to shore, however Shubun obstructs the view with a rock, allowing only half of the bodies to be visible. The two are bent over, and seem to display exhaustion as they “return home” to this solitary cabin, perhaps from the labors of their long journey out into this wilderness. The mountains expand into the distance and eventually lost detail as the atmospheric background swallows them, giving the piece a true sense of the never ending expanse of nature.

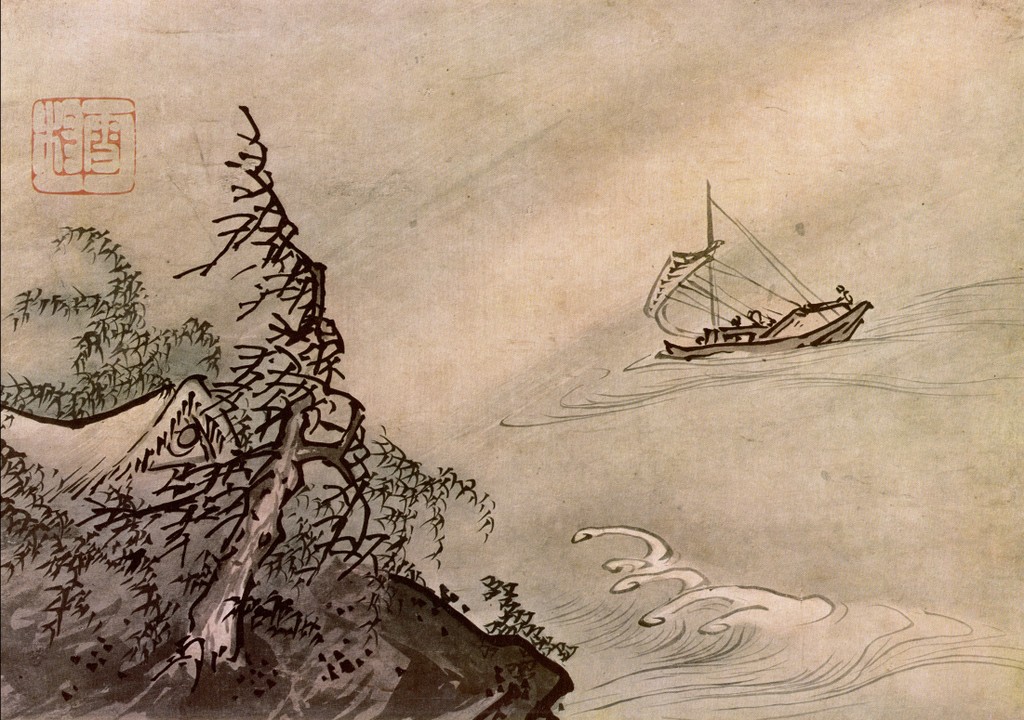

5) “Wind and Waves” by Season Shukei

- 1504 – 1589, Muromachi Period

- 8.7 in. height.

- Located in the Nomura Art Museum in Kyoto, Japan.

- https://library.artstor.org/#/asset/HUNT_56452

This painting has numerous differences from the four other paintings, yet is nevertheless important and relevant to the overarching collection of Zen Buddhist landscapes. I believe the painting is a fitting follow up to the “Returning Home” painting due to the subject of the boat. Perhaps this painting depicts the journey the Buddhist philosopher embarked on in search of this rustic and isolated lifestyle. The details of the sharp, barren tree and curling waves create a sense of movement and animation in the piece, yet with the balance of ambiguous space and left out details, the painting maintains this feeling of aloneness and careful contemplation. I think the inclusion of this piece allows the viewer to recognize the stillness in the four other chosen pieces. The animation in this work however can still be attributed to the concept of Sabi, which describes the delicate movement of time and the universe, and therefore fits into this collection for the purpose of exposing a deeper philosophical statement behind the thoughtful and simple landscape paintings of the Japanese Zen Buddhists.

Visual Sources

https://library.artstor.org/#/asset/HUNT_56443

https://library.artstor.org/#/asset/AIC_760024

https://library.artstor.org/#/asset/ARTSTOR_103_41822000270775

https://library.artstor.org/#/asset/24628527

https://library.artstor.org/#/asset/HUNT_56452

Textual Sources

Fraleigh, Sondra Horton. “Zen and Wabi-Sabi Taste: Setsuko Yamada’s Performance in Toronto.” In Dancing Into Darkness: Butoh, Zen, and Japan, 214-27. Pittsburgh, Pa.: University of Pittsburgh Press, 1999. Accessed May 14, 2021. doi:10.2307/j.ctt5hjp8s.27.

Lippit, Yukio. “Of Modes and Manners in Japanese Ink Painting: Sesshū’s “Splashed Ink Landscape” of 1495.” The Art Bulletin 94, no. 1 (2012): 50-77. Accessed May 14, 2021. http://www.jstor.org/stable/23209211.