By Natalia Hall and Mia Webb

What was the original purpose of the torii gate and how has it changed throughout time?

The Torii Gate is an iconic and significant symbol of Japan and the Shinto religion. It originated in Japan, and its significance and function have evolved and changed many times. The torii gate has been a symbol of life, growth, vitality, protection, and renewal for thousands of years. In the Shinto religion, it is believed that all people are inherently good and that if someone is evil, that is because of evil spirits. Originally, the torii gate was associated with Shintoism, Japan’s indigenous religion. So, one of the original purposes of the Torii Gate was to protect those around it from evil spirits. This is because, in Japan and Shintoism, the color red (specifically bright, vermillion red) is said to repel evil spirits. In tandem with this purpose of the Torii gate, another one of its original functions is that it marks the entrance to a sacred space and a separation between the spiritual world and the secular world. It was believed that those who passed through a torii gate were purified and protected by the gate.

A good and famous example of the connection between torii gates and religion is the “Itsukushima Shinto Shrine”. This torii gate was constructed by Saeki no Kuramoto during the 6th century. It is about 50 feet tall, made of decay-resistant camphor wood, painted red, and located in Itsukushima, Japan. Itsukushima directly translates to “island dedicated to the gods,” and the island and torii gate is dedicated to the Shinto goddesses of seas and storms. This torii gate is also a pure Shinto shrine, meaning no births, deaths, or burials are allowed on or near the island. If someone is pregnant and coming close to their due date, they must leave the island and go to the mainland to give birth. It is the same with those who have terminal illnesses or are of old age. They must leave the island and pass away on the mainland. This aspect highlights the identity of the torii gate. It seems as though the artist made this sacred torii gate for the island itself and not those who live on the island. This identity and the torii gates global influence contributes to “Japonism”, as it focuses on issues of cultural significance and religion.

Torii gates are also a large symbol of connection to nature. The Shinto religion has a profound connection to nature, which can be seen in the location and function of many torii gates around Japan. This connection comes from the belief that many Japanese deities and spirits inhabit different aspects of nature, like mountains, rivers, trees, and plants. Many Shinto shrines and torii gates were constructed at the foot of a mountain, outside of a forest, next to a stream, and around other natural settings. These sites are sacred and emphasize the connected nature of the Earthly and the spiritual world. Because of this, both the Shinto shrines and nature itself have much spiritual significance. The “Fushimi Inari-taisha Shrine” in Tokyo is a good example of this. It is a Senbon torii, meaning thousands of red torii gates are lined up together to make a path. This path leads to the base of a mountain. When people walk through the Fushimi Inari-taisha Shrine, they embark on a spiritual journey that represents a connection to Shintoism and nature. Surrounding the thousands of torii gates, is trees, bushes, flowers, rocks, grass, and dirt. All the aspects of nature encourage the visitor to ground themselves and take in the world and spirits around them.

A good example of how torii gates connect with nature in Japanese art is Japanese woodblock prints. The woodblock print “Noboto Bay (Noboto no ura), from the series Thirty-six Views of Mount Fuji (Fugaku sanjūrokkei)” by Katsushika Hokusai, highlights this connection. Created during the Edo period in Japan, a time when the Shinto religion began to expand and grow, Noboto Bay emphasizes the intrinsic connection between humanity, religion, and the natural world. Instead of the torii gate being the usual red color, it is painted green. The color green is associated with nature and represents vitality, growth, and spiritual renewal in Shintoism. This woodblock print contains views of mountains, hills, water, trees, and grass, which connects to the idea that a lot of Shinto shrines are placed near natural settings like these. The nature and torii gate imply that those who come to Noboto Bay are entering a sacred space or spiritual journey. Another aspect of this piece that emphasizes the religious and sacred context is the view of Mount. Fuji is in the background. Mt. Fuji is one of the most sacred places in Japan and the Shinto religion. The view of Mt. Fuji is seen through the torii gate, showing the connection between these two extremely sacred sites. This aspect displays the identity of this piece as Mt. Fuji has been a place for pilgrimage, meditation, and worship for centuries, just like the torii gate. Hokusai most likely put these two sacred sites together to show the relationship between humanity, nature, and religion. This aspect can also answer the question of “What is Asian Art”? because of the content of this piece and the relationship between the two sacred places that are highlighted in it.

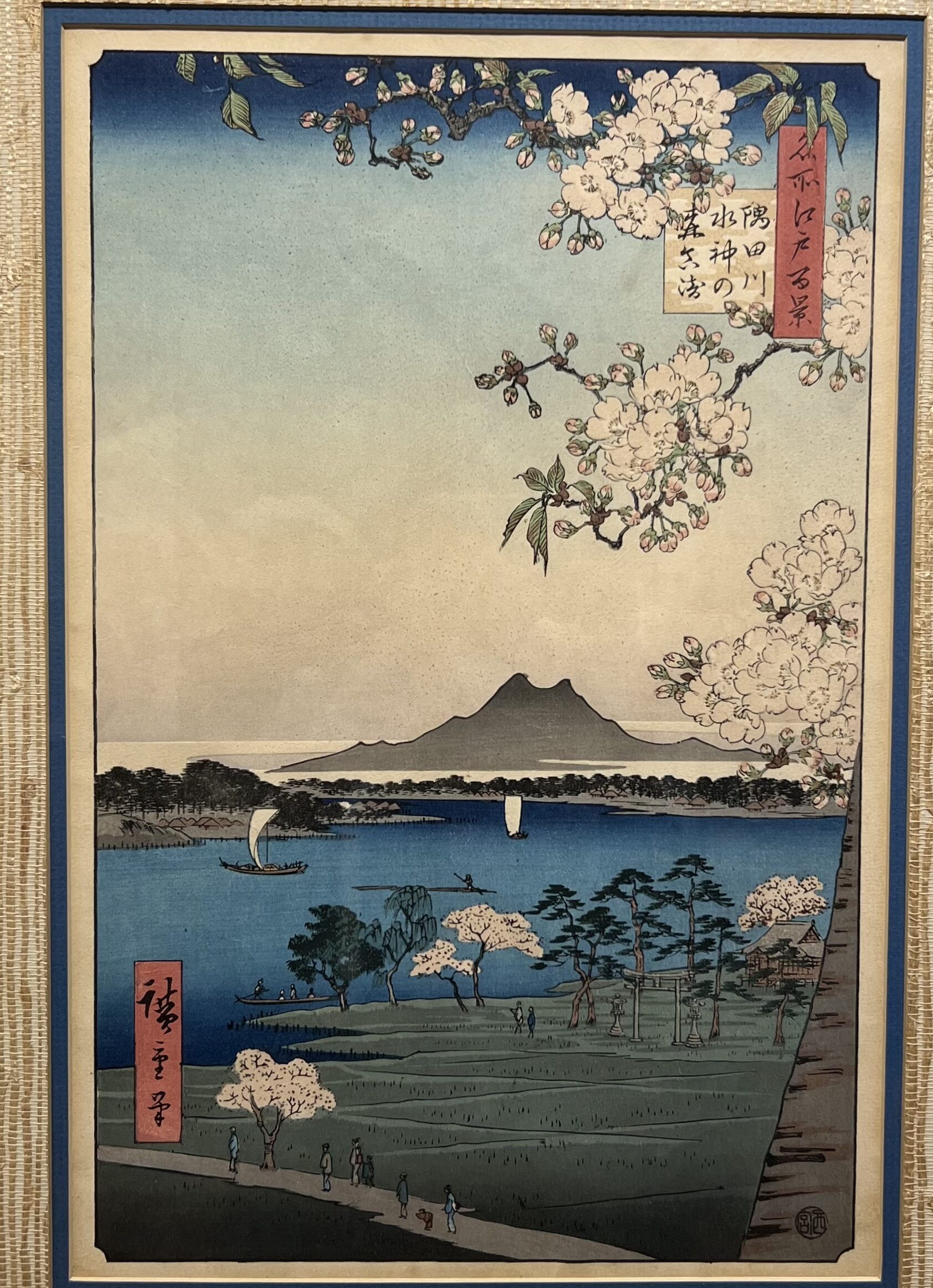

Similarly, the woodblock print “Towards Mt. Fuji” by Utagawa Hiroshige. Created during the Edo period, this woodblock print was influenced by Hokusai’s series of “Thirty-Six Views of Mount Fuji.” This piece also shows the significance and interconnectedness of nature and religion in Shintoism. Nature represents vitality, growth, and renewal, and this is a big part of the identity of this piece. It displays hills, mountains, trees, flowers, water, and grass, just like Hokusai’s piece. Both represent the sacredness of Mount Fuji and the torii gate. The cherry blossoms in the foreground signify the fleeting nature of life and how important spirituality is in a person’s life. If a person is able to feel connected to nature, they are connected to their religion. “Towards Mount Fuji” shows a reverence for artistic tradition as well. The act of stamping art shows a sense of respect for ancestral customs and values. This cultural practice gives a sense of the context for this woodblock print. It is important to view this piece in its cultural as well as geographical context to understand its meaning.

Since its conception, the symbolism of the torii gate has gone beyond its original meaning and is now not only an iconic symbol of the Shinto religion but also an iconic symbol in Japanese art, literature, and media. They have also expanded outside of their religious context and can be seen in non-religious contexts like parks, gardens, and transportation hubs inside and outside of Japan. In modern times, torii gates are found in spiritual and secular contexts but are still commonly found at Shinto shrines. At these shrines they have been and will continue to be a symbol of the energy of life, growth, vitality, protection, and renewal. The torii gate has transformed from its original form and function and is now widely recognized as an integral part of Japanese culture and religion. The original and new functions of torii gates answer the question “What is Asian art?” and highlight Japonism because of their profound spiritual significance, symbolism of cultural heritage, and connection to people and nature.

Has the religious significance changed? And if so, how?

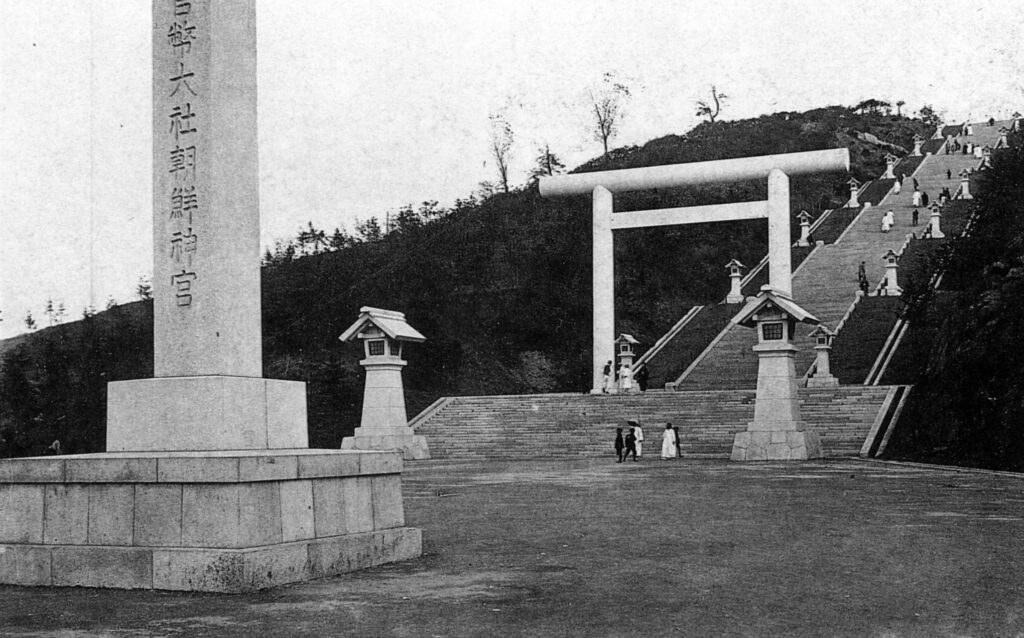

As was previously mentioned, Shintoism originated in Japan and can be traced back to 300 BC. Regarding the religious significance of a Torii gate, the most significant shift in Shinto practice was during the Japanese colonial period in Korea (1910-1945). During this time, the Japanese government established government-sponsored Shinto shrines in their colonial territories to indoctrinate people into Shinto. An example of a colonial-period Shinto shrine is The Chōsen Shrine. Built in 1925, the shrine resided in Seoul for 20 years until its destruction in 1945. The torii gate in the Chōsen shrine is white with a simplified form. Void of the standard traditional torii gate features, such as an additional horizontal bar, the Chōsen torii embodies the changing values of Shinto. State Shinto was Imperial Japan’s ideological use of traditional Shinto practices where the state-controlled shrine finances and training regimes for priests. The Japanese government exploited Shintoism to combat foreign resistance, emphasize the emperor’s divinity, and impede the practice of local traditions.

Today, a big part of the shift from pure spiritual significance to being placed in non-religious contexts stems from tourism and modern adaptations of the Torii gate. With the rise of tourism in Japan, torii gates have become an iconic symbol of Japanese culture. They attract tourists worldwide and are often featured in travel brochures, advertisements, and social media to show Japan’s rich cultural heritage. Many modern interpretations of torii gates can be found in non-religious settings, like at the entrances of schools, businesses, neighborhoods, or train stations, like the following example.

Kanazawa Station-Eastern Facade, Architect: Ryuzo Shirae, Shirae Associates, ca. 2005, Wikimedia Commons, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.

phptitle=File:Tsuzumimon_Gate_in_front_of_Kanazawa_

Station_in_the_morning_20150121.JPG&oldid=503254174 (accessed March 4, 2024).

Located in Kanazawa, Japan, the Tsuzumimon Gate in Kanazawa station has visual and functional similarities to a traditional torii gate. Though there is no apparent religious significance, through wood, vertical pillars, and a horizontal crossbar, the shape of the gate resembles a torii. The structure is fluid, with the vertical wooden pillars in an outward spiral. As the entrance to an essential transportation hub, the gate stays true to its authentic purpose: to serve as a threshold between states of being.

Torii gates have also been used as art pieces and sculptures outside of Japan. Two examples can be found in Benoît Maubrey’s unconventional Shrine Torii and Michael Le Grand’s abstract Steel Torii. For the 2015 Kobe Biennale in Japan, sculptor Benoît Maubrey utilized recycled speakers to form an interactive torii gate. With connected speakers, amplifiers, mixing boards, Bluetooth receivers, and telephone answering systems, individuals could play music or call and speak through the sculpture. The intention behind Maubrey’s design is to amplify voices and encourage connections. Located in Japan, the speaker Shrine Torii maintains geographical roots while opening up lines of communication for those who interact with the piece.

In contrast, Michael Le Grand’s Steel Torii lacks many qualities defining a torii. Created in 1999, the Steel Torii is placed at the entrance of the Australian National University School of Art and Design. The intention behind the modern torii is to serve as a symbolic gateway into the art world. Somber and dramatic with calligraphic curves, Le Grand’s sculpture dismantles the stability and confidence that typically emanates from a traditional torii. While aesthetically captivating, the modern interpretation and symbolic usage of the gate in front of the ANU art school brings into question the authenticity behind the sculpture. Regarding ties to Japan, ANU is the most international university in Australia and has Australia’s largest network of scholars with expertise in Japan. Despite this, it is essential to question Le Grand’s intention: Is the Steel Torii a genuine attempt to connect to Shinto/Japanese culture, or is it yet another example of Japonism?

_front_of_the_ANU_School_of_Arts_building,_by_Michael_

Le_Grand.jpg&oldid=679799910 (accessed April 28, 2024).

Because of tourism and modern interpretations, torii gates have become a symbol of national pride. Still, this shift to a tourist attraction versus a symbol of the indigenous religion of Japan begs a big question: Is the use of torii gates in modern/non-religious settings and as tourist attractions religious/cultural appropriation or appreciation? Torii gates have a deeply rooted sacred nature, marking spiritual journeys in Shintoism. When these symbols are taken out of their original context and used non-religious or commercial, there is the risk of disrespecting their sacred meaning. Using a torii gate only for aesthetic consumption without understanding or trying to understand their spiritual meaning and original function can be seen as appropriation and sacrilege. If torii gates are used in non-religious contexts, their spiritual ties and sacred practice in Japanese culture must be acknowledged. The exploitation of religious symbols can lead to disrespect, marginalization, and the reinforcement of stereotypes. This is not to say that one who does not practice Shintoism or live in Japan cannot use the symbol of a torii gate. It means that if they do, they must make sure they approach the use of torii gates with understanding and respect for their spiritual and cultural significance.

In our examples, it is essential to recognize the geographical location, like that of Hokusai’s Noboto Bay woodblock print; the current location is necessary when assessing historical context. Currently located at the Met, the woodblock print traveled from Japan to the U.S. This fact makes you ponder the journey of the print–how many hands did the piece go through before arriving at the Met? Similarly, for the Chōsen Shrine, an image of the torii gate alone does not reveal the historical background and socio-political status of Shinto shrines in the early 20th century. As previously mentioned, the Chōsen Shrine no longer exists–a truth we would not have acquired without accompanying written information. Our context becomes limited when viewing representations of torii through our computer screens. By examining the details of Hokusai’s Noboto Bay woodblock print in person, walking through the red torii of the Fushimi Inari-Taisha Shrine, or listening to the sounds of Benoît Maubrey’s speaker torii, our analysis would significantly change. Experience provides much more context than an image ever could.

We put our examples in the order that they are in to show the evolution of the physical and religious torii gate. They are split up into ancient/older examples and modern-day examples to signify how much has changed over time. Three out of four of the older examples are from the Edo period, a time when then Shinto religion was flourishing. The fourth example is from the Heian period which was a time more focused on Buddhism. The modern examples are all from the 20th and 21st centuries to signify that the power of torii gates still remains even if they do not look the same as when they were first created.

Bibliography and References

- KASULIS, THOMAS P. “Entering Through the Torii.” In Shinto: The Way Home, 9–37. University of Hawai’i Press, 2004. http://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt6wr417.7.

- This article speaks on the experiences of those who practice Shintoism and those who “feel Shinto.” Kasulis talks about how spirituality is met with a sense of mystery, wonder, and awe. This relates to our project because the Torii Gate is a shrine of wonder and mystery. People pass through torii gates in order to connect with the spiritual realm.

- Michio, Nakajima. “Shinto Deities That Crossed the Sea: Japan’s ‘Overseas Shrines,’ 1868 to 1945.” Japanese Journal of Religious Studies 37, no. 1 (2010): 21–46. http://www.jstor.org/stable/27822898.

- This article discusses how Imperial Japan used Shinto shrines to influence colonized Taiwan and Korea. The Japanese government established government-sponsored Shinto shrines in their colonial territories to indoctrinate native people into Shinto and convert them into followers of State Shinto. The Japanese government exploited Shinto to combat foreign resistance and impede the practice of local religious traditions.

- Itsukushima Shinto Shrine.” UNESCO World Heritage Centre. Accessed March 4, 2024. https://whc.unesco.org/en/list/776/.

- Keane, Marc P. “Japanese Entrances: Cultural Symbols in the Landscape.” Landscape Architecture 78, no. 6 (1988): 120–25. http://www.jstor.org/stable/44676721.

- “Torii.” Wikipedia, April 8, 2024. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Torii./

- Centre, UNESCO World Heritage. “Itsukushima Shinto Shrine.” UNESCO World Heritage Centre. Accessed May 12, 2024. https://whc.unesco.org/en/list/776/.

- Guide, Dive! Hiroshima Official. “About Itsukushima Shrine.” The Official Guide to Hiroshima – Travel and Tour Information. Accessed May 12, 2024. https://dive-hiroshima.com/en/feature/world_heritage-about_itsukushima/.

- Japanese, Katsushika Hokusai. “Katsushika Hokusai: Noboto Bay (Noboto No Ura), from the Series Thirty-Six Views of Mount Fuji (Fugaku Sanjūrokkei): Japan: Edo Period (1615–1868).” The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Accessed May 12, 2024. https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/56216.

- “Kanazawa Station.” Wikipedia, May 10, 2024. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kanazawa_Station.

- “Brany Torii.” Wikimedia Commons. Accessed May 12, 2024. https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?title=File%3ABrany-torii.jpg&oldid=831666815.

- “Torii Painted Steel Sculpture, Located at the Front of the ANU School of Arts Building, by Michael Le Grand.Jpg.” Wikimedia Commons. Accessed May 12, 2024. https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?title=File%3ATorii_painted_steel_sculpture%2C_located_at_the_front_of_the_ANU_School_of_Arts_building%2C_by_Michael_Le_Grand.jpg&oldid=679799910.