Introduction

Musical instruments have long been depicted in Chinese visual arts such as painting, sculpture, and reliefs. This semester, I decided to choose the topic of the evolution of musical instruments in Chinese art. This paper aims to explore how depictions of musical instruments in Chinese visual arts have evolved over time and what these changes indicate about the transformation in musical practices and preferences in Chinese culture. Understanding the evolution of musical instrument depictions in Chinese art is important for people to discover the cultural, technological, and social transformations in China. This exploration reflects broader trends in artistic expression, societal values, and the philosophical framework within which music was appreciated and practiced. The analysis is supported by a review of artifacts from a series of collections such as the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Henan Museum, the Cleveland Museum of Art, and Gettysburg College Musselman Library. Additional scholarly resources include academic journals, such as Visual Arts and Music in Traditional Chinese Art System, and Musical Instruments of Chu and Zeng Excavated from Hubei such books on Chinese musical instruments and art history, ensuring a comprehensive understanding of the subject.

Literature Review

The first source from the Metropolitan Museum of Art discusses the discovery of bone flutes dating back to around 6000-7000 BCE found in Jiahu, a Neolithic site in China. These flutes, carved from the hollow bones of the red-crowned crane, are considered the earliest playable musical instruments ever found. They were likely used in rituals and ceremonies by early Chinese cultures.

The second source, a Nature paper by Zhang et al. (1999), provides more details on these Jiahu bone flutes.Through microscopic analysis, the authors confirmed that the instruments could be played to produce sound, making them the “oldest playable musical instruments” found to date. The flutes have between 5-7 holes and were made from the underarm wing bones of the red-crowned crane. Their discovery sheds light on the development of music and organized rituals in early prehistoric China.

The third source by Andrijauskas (2016) discusses the place of musical instruments more broadly within traditional Chinese art and culture. Music was seen as closely tied to cosmology, rituals, and the establishment of social order from very ancient times. Musical instruments thus had important symbolic meaning beyond just producing tones. Because of that literature, I am able to find connections between rituals and music back in prehistoric times.

The last source by Liu Yang focuses specifically on musical instruments excavated from ancient Chu and Zeng culture in Hubei province, dating back over 2000 years. These include chimes, lithophones, clay ocarinas, and bone flutes that demonstrate an advanced musical tradition in these regions during the Warring States period around the 5th – 3 rd centuries BCE.

Visual Analysis

The First Object: Bone flutes

Date: Neolithic Period (7000 BC to 5700 BC)

Culture: China

Medium: ulnae (wing bones) of the red-crowned crane

Dimensions: 10 1/16 in. x 10 ft. 2 3/4 in. (25.6 x 311.8 cm)

Credit Line: Gift of George D. Pratt, 1933

The image above displays a collection of ancient flutes, each made from bone, with various numbers of holes. These holes, typically ranging from 5 to 7 per instrument, suggest a sophisticated understanding of musical scales even in ancient times. The presence of such instruments indicates that music played a significant role in daily life, likely being used in rituals, ceremonies, and everyday entertainment. While the exact functionality and performance context remain unclear, their widespread presence indicates an early flowering of musical behaviors that are highly correlated with prehistoric spirituality. Also, the craftsmanship and preservation of these flutes show the technological advancements of their creators. Dating back to the Neolithic period, these flutes have burnished surfaces and carefully hollowed-out finger holes.

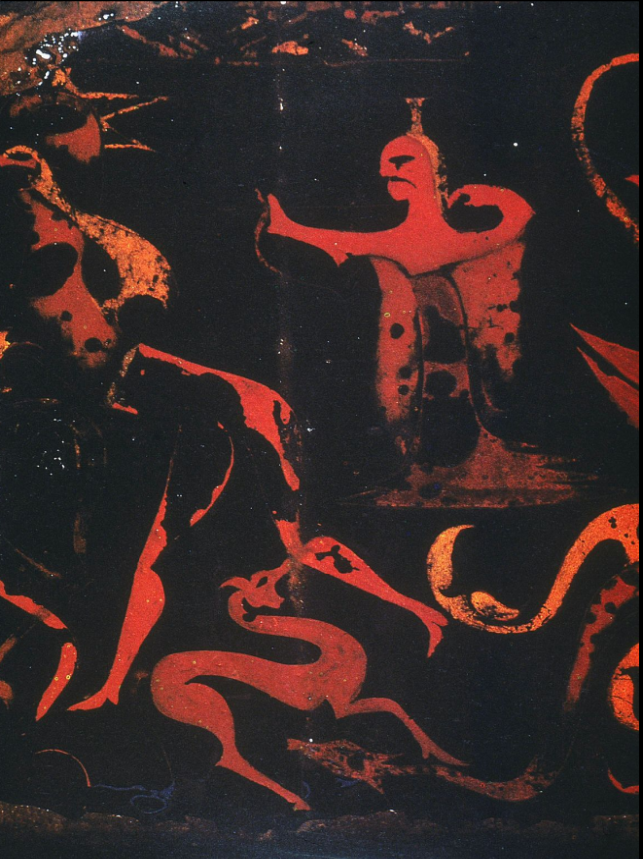

The Second Object: Partial Painting of the Tomb of Chu

Period: Zhou dynasty (1122–221 B. C.)

Culture: China

Medium: Lacquer

Dimensions: 40 * 100 cm

Credit Line: Henan Sheng Bo Wu Guan

Tomb of Chu: lacquer chinese harp: det.: mythical figures. Place: Henan Sheng bo wu guan.

The image above is a piece of ancient artwork featuring a figure amidst what seem to be serpentine forms or motifs. It comes from the Zhou dynasty. The dominant red color against a dark background suggests a vibrant and symbolic representation. The figure appears to be engaged in an expressive gesture, dancing, and performing a ritual. Surrounding the central figure are sinuous objects that resemble dragons, also in red, enhancing the supernatural theme and the importance of music at that time. Chu tomb artifacts are renowned for their sophisticated artistry,

The Third Object: The Seated Musician

Period: Tang dynasty (618–907)

Culture: China

Medium: White marble

Dimensions: H. 5 1/2 in. (14 cm); W. 3 1/8 in. (7.9 cm); D. 2 3/4 in. (7 cm)

Classification: Sculpture

Credit Line: Purchase, Friends of Asian Art Gifts, 2006

The image above depicts a sculpted figure of a seated musician, carved from marble or similar light-colored stone. The figure is sculpted with great details and naturalism since workers highlighting the animated poses and expressions. The musician is portrayed in a kneeling position, playing a flute-like instrument. The figure’s facial expression is serene, suggesting a peaceful and contemplative mood, that aims to convey tranquility and introspection. This sculpture came from the Tang Dynasty. Because of the detailed carving of the figure’s attire and the facial features, the artwork reflects the high artistic achievement of the period. Music got easier for the public to access, even though flutes were usually played in the court.

The Fourth Object: In the Palace

Date: Southern Song dynasty (1127 – 1279)

Culture: China

Medium: Handscroll; ink and light color on silk

Dimensions: Painting: 28.5 x 168.6 cm (11 1/4 x 66 3/8 in.); Overall: 29.7 x 306.1 cm (11 11/16 x 120 1/2 in.)

Credit Line: John L. Severance Fund 1976.1

The image above shows a traditional East Asian scroll painting, showcasing several female musicians participated in playing different instruments. The figure are depicted in a very linear style of ink paintings. The attire and hairstyle of the woman, along with the types of musical instruments, which include stringed and wind instruments, reflect the cultural context of the artwork. Culture is flexible at that time. Such images often aim to capture the elegance and serenity of musical performances within aristocratic or royal settings of the period.

The Fifth Object: Lady Su Hui and Her Verse Puzzle

Artist: In the style of Qiu Ying (Chinese, ca. 1495–1552)

Period: Ming dynasty (1368–1644)

Date: 16th century

Culture: China

Medium: Handscroll; ink and color on silk

Dimensions: Image: 10 1/16 in. x 10 ft. 2 3/4 in. (25.6 x 311.8 cm)

Classification: Paintings

Credit Line: Gift of George D. Pratt, 1933

The image above is a traditional East Asian painting in the Tang dynasty, depicting a group of musicians seated on a decorative rug, engaging in a musical performance. The setting appears tranquil, possibly a garden, as suggested by the floral motifs and rock formations in the background. Musicians are shown playing various traditional instruments, contributing to an overall scene of cultural and artistic activity. The style of painting, with its subdued color palette and detailed depiction of the figures and their attire, reflects the appreciation for music and art in Chinese culture.

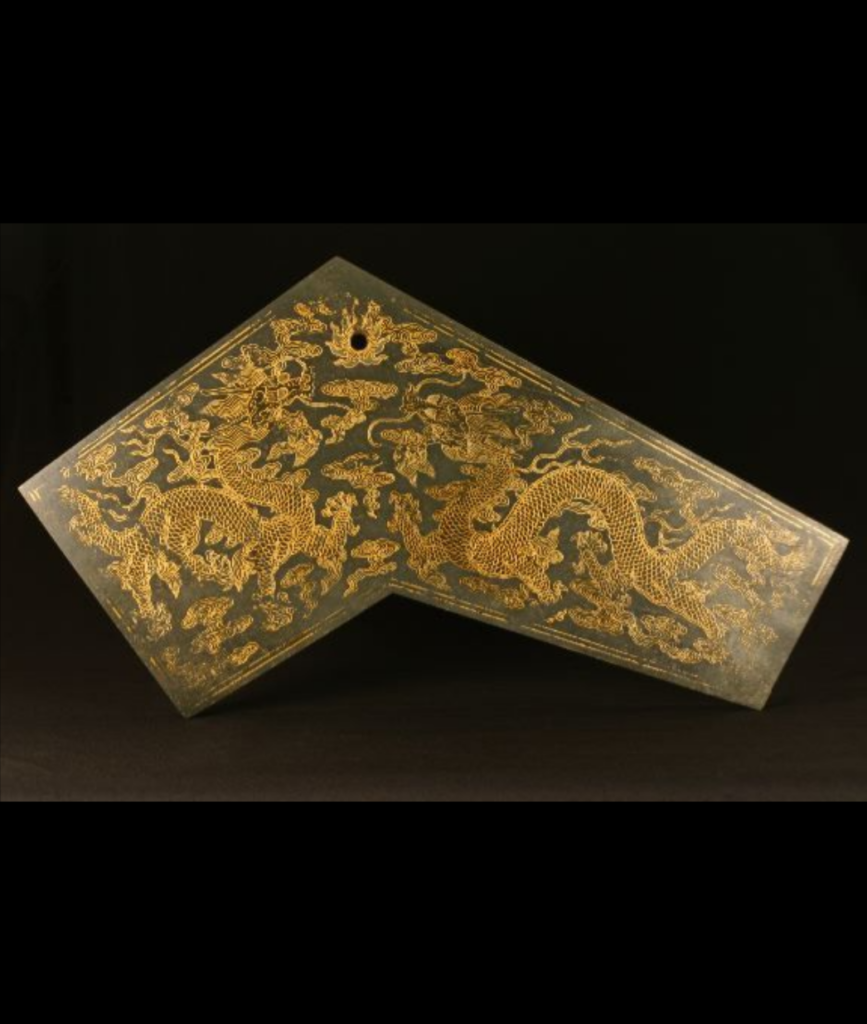

The Sixth Object: Chime stone Tê-ch’ing

Period: Qing dynasty (1644 –1911)

Date: 19th to 20th century A.D.

Culture: China

Medium: Jade

Dimensions: Length: 48.24cm; Width: 18.4cm; Thickness: 2.9cm

Classification: Jade

Credit Line: Special Collections and College Archives, Musselman Library, Gettysburg College

This chime stone Tê-ch’ing (or “single sounding stone”) has the shape of a carpenter’s square. It is one of the oldest musical instruments in China, dating back to the Shang Dynasty, and was often used in ritual music in temples. During the Qing Dynasty, the performance of ritual music also helped to legitimize the emperor’s rule. The shape of the tê-ch’ing was made to exact dimensions so that it could faithfully reproduce the sound of the triple octave below huang-chung when struck correctly with a special hammer. A hole was drilled in the apex through which a “gut cord” was inserted to suspend the instrument within a narrow frame (of wood, iron, or stone). The inverted V-shape of the gongs was the standard shape of a stone instrument known as the bian-ch’ing, which was generally smaller than the tê-ch’ing. It consisted of sets of 16 pieces, all of equal length and width, suspended from a single frame. Each side of the jade tê-ch’ing is engraved in the stone and filled with gold pigment. It is decorated with a detailed design of the auspicious dragon swirling among the clouds and pursuing a flaming jewel on the surface, as well as registers on the edges of the clouds and characters.Some faded areas on the surface of the bell reveal red pigment under the gold inlay. On the shorter edge of the instrument, the date of the piece is engraved in kai shu (regular script), meaning “made during the twenty-ninth year of Emperor Ch’ien Lung’s reign”. The longer edge bears two characters, also written in kaishu, meaning “golden bell” (huáng zhong).

The Seventh Object: Huqin

Period: Qing dynasty (1644-1911)

Date: 19th century

Geography: China

Culture: Chinese

Medium: Wood, python skin, cane, ivory (?)

Dimensions: H. 29 15/16 × D. 4 5/8 × Belly diam. 2 7/16 in. (76 × 11.8 × 6.2 cm)

Classification: Chordophone-Lute-bowed-unfretted

Credit Line: The Crosby Brown Collection of Musical Instruments, 1889

The image above is a traditional musical instrument known as a “morin khuur” or Mongolian horsehead fiddle. During the Qing dynasty, it is called huqin. It is a fiddle with two strings made of horsehair and a trapezoidal wooden body. This 19th-century instrument represents a traditional form, used both in classical and folk music settings, since huqin often associated with the nomadic lifestyle and vast landscapes of Mongolia. Huqin, also known as horsehead fiddle, holds a revered place in Mongolian musical traditions and is commonly used in a variety of performances, from folk music to symphonic orchestration.

Typology

My chosen objects are in chronological orders because I would like to see the evolution of the musical instruments throughout the history.

Historical Background and Intellectual Underpinnings

Neolithic Period (c. 8000 – 2000 BCE)

Some of the earliest evidence of musical instruments in China comes from bone flutes found in Neolithic burial sites like Jiahu. Music’s ritualistic role is important in prehistoric times. However, because of the far away time period, there are neither visual records of the instruments nor musicians artworks.

Zhou Dynasty (1046 – 256 BCE)

The Zhou is regarded as a formative period established musical theory and practices in the Chinese tradition. Writings in the Classic of Poetry and Records of Music describe courtly entertainment known as ya music (雅乐) and yayue dances accompanied by chimes, zithers, and drums. Music was tightly regimented based Confucian philosophy promoting social harmony. The Zhou period is considered the golden age that codified and instiutionalized music theory and ritual performance in ancient China. The philosophical writings of this era, particularly the Analects of Confucius and the Classic of Rites, expounded on the cosmic significance of musical harmoney and its role in maintaining social order.

Tang Dynasty (618 – 907 CE)

Following the prolonged political fragmentation after the Han dynasty, the Tang rulers purposefully revived and promoted traditional musical and artistic traditions as a mean of solidifying imperial legitimacy. Imperial academics compiled comprehensive musicological knowledge and performance canons. There are lots of musical entertainments and spectacles in the Tang court life.

Silk Road plays an important role in cultural exchange. The Tang capital Chang’an was a bustling cosmopolitan center linked to far-flung trade routes across Central Asia, India, and Persia. An influx of foreign merchants, emissaries, monks, and entertainers facilitated the reciprocal dissemination of musical styles, instruments, and performance traditions. Chinese percussive ensembles integrated Western instruments like oboes, lutes, and hand drums from regions like Kucha and Khotan.

On the other hand, there is also a rise in secular entertainment arts. In parallel to elite court traditions, vibrant streams of profane musical entertainment genres developed. Musicians began playing regional songs that are connected to the emergent medieval opera, such as theatrical arts.

Song Dynasty (907 – 1368 CE)

The Song period witnessed the ascendance of neo-Confusian thought and philosophies that emphasized cultivation of the arts as a path toward moral self-improvement. This helped drive renewed scholarly interest in reviving and reconstructing ancient musical theories. The imperial court sponsored comprehensive musicological systems and compositional rules.

With the blossoming of cities and maritime trade, a new class of wealthy scholars emerged at this time. This helped foster a vibrant musical culture centered around elite social gatherings called yaji where friends would come together to make music, compose poetry, and engage in shared aesthetic pursuits. Artistic depictions of such convivial musical scenes proliferated.

Even as imperial powers promoted reconstructed “orthodox” musical canons, the Song still have the flourishing regional folk opera genres. These popular performance traditions incorporated a diverse array of instruments with more plebian associations that contrasted the aristocratic yang and yayue ritual music. Visual representations preserved the instrumental combinations used in such regional operas.

The prosperous Song culture catalyzed innovations in musical instrument design and manufacturing techniques. There is new development of zither forms, Se adapted from ancient qin. Wind instruments in particular diversified with the advent of the Xiao and domesticated vertical bamboo flutes derived from influences across Southeast Asia and regions along the maritime trade routes.

Ming dynasty (1368 – 1644 CE)

The Ming era viewed the neo-Confusion philosophy as the official state ideology, leading to great effort to revive and reinforce ancient music traditions. While promoting Confusion ideas, Ming court culture still maintained an appetite for foreign musical influences absorbed during the preceding Yuan dynasty established by the Mongols. Imperial entertainments frequently featured dance performances choreographed in the Yuan zaju opera style accompanied by musicians playing lutes, oboes, and percussion of Central Asian/Persian origins dating back to Tang era introductions along the Silk Road.

The Ming also represented a high point of material cultural sophistication catalyzed by advances in manufacturing techniques and global maritime trade expansion. This enabled more elaborate production of musical instruments, such as the construction of monumental bianqing chime installations consisting of precisely calculated resonant bronze components. Meanwhile, rising gentry prosperity fostered greater accessibility of once aristocratic instruments like guqins.

Qing dynasty (1644 – 1911 CE)

The Qing dynasty represented an era of concerted imperial efforts to purify musical practices from perceived foreign influences that had accumulated over previous dynastic interactions with non-Han cultures. This inward focus institutionalized orthodox Confucian musical values manifested in ceremonial protocols, instrument construction, and pentatonic musical theory. However, folk musical streams continued flowing in parallel, evolving organically while periodically reviving ancient regional traditions as well.

Implication of Evolution

The evolving depictions of musical instruments in Chinese visual art shows a lot in the aspect of cultural, social, and technological developments throughout Chinese history. The portrayal of musical instruments in art illustrates the cultural exchanges, particularly the Huqin in the Qing dynasty, with the influence the Mongol people bring from the west. This cross-cultural interaction enriched the Chinese musical tradition, introducing new instruments and styles that were incorporated into the society. This blending promotes China’s openness in the music industry, and helps Chinese people adapt and integrate diverse cultural elements, which has been a key factor in the longevity and dynamism of its civilization.

Socially, the changing depictions reflects shifts in societal structures and values. For instance, during the Song and the Ming dynasty, both court music and local folk songs are popular in the public. Moreover, during the Qing dynasty, the depiction of ritual music in art underscores the use of music as a tool for reinforceing the emperor’s authority and promoting social harmony, aligning with Confusian values that were deeply embedded in the social and political life of the period.

Together, these aspects underscore how the artistic depiction of musical instruments serves as a window into the broader historical and cultural currents of Chinese society, reflecting its evolving values, and the complex interplay of local traditions with external influences.

Bibliography

Andrijauskas, Antanas. 2016. “Visual Arts and Music in Traditional Chinese Art System.” Music in Art 41 (1-2): 165–87. https://www.jstor.org/stable/90012994.

Artstor. n.d. “Artstor.” Library.artstor.org. Accessed May 12, 2024. https://library.artstor.org/#/asset/ARTSTOR_103_41822003075130.

“Chime Stone Tê-Ch’ing.” n.d. Gettysburg.contentdm.oclc.org. Accessed May 13, 2024. https://gettysburg.contentdm.oclc.org/digital/collection/p4016coll6/id/202/.

“In the Palace | Cleveland Museum of Art.” n.d. Www.clevelandart.org. Accessed May 13, 2024. https://www.clevelandart.org/art/1976.1.

Liu, Yang. 2011. “Musical Instruments of Chu and Zeng Excavated from Hubei.” Liu Yang, Homage to the Ancestors: Ritual Art from the Chu Kingdom, Sydney: Art Gallery of New South Wales, January. https://www.academia.edu/39060449/Musical_Instruments_of_Chu_and_Zeng_Excavated_from_Hubei..

Marius Masalar. 2017. “Photo by Marius Masalar on Unsplash.” Unsplash.com. October 12, 2017. https://unsplash.com/photos/tilt-selective-photograph-of-music-notes-rPOmLGwai2w.

Tedesco, Authors: Laura Anne. 2000. “Jiahu (Ca. 7000–5700 B.C.) | Essay | the Metropolitan Museum of Art | Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History.” The Met’s Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History. October 2000. https://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/jiah/hd_jiah.htm#:~:text=The%20flutes%20were%20carved%20from.

Zhang, Juzhong, Garman Harbottle, Changsui Wang, and Zhaochen Kong. 1999. “Oldest Playable Musical Instruments Found at Jiahu Early Neolithic Site in China.” Nature 401 (6751): 366–68. https://doi.org/10.1038/43865.

2020. Metmuseum.org. 2020. https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/73218.

2021. Metmuseum.org. 2021. https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/51584.