Though we might overlook the clothes we wear as just a part of everyday life, they hold great power over how we present ourselves and interpret others. Historically, clothing has always been used as a way to communicate status, power, wealth, gender, and nationality. The ways in which clothing does this can also shift through time, and those changes can illuminate a lot about the ideals of society at that time. Chinese traditional clothing is no exception to this, and by examining the different types of traditional dress throughout history, we can see how fashion has impacted the politics and community of Chinese people across history. In this article, we will examine both how shifts in traditional Chinese clothing reflect dynamics of power, culture, and gender in Chinese history, as well as how traditional dress can unify or divide a diverse nation. This typological analysis will cover three main types of traditional clothing, Hanfu (1600 BCE – 1644 CE), Manfu (1644 CE -1911 CE), and Qipao (mid-1920s onward).

Hanfu

From the Qin to Ming dynasties, China was ruled by the Han people, the ethnic majority of China [DL: This does NOT apply to all dynasties–the Liao, for instance, was ruled by the Khitan/Qidan]. Han China was very prosperous and influential, and the art that was produced during that time was renowned for its high quality and careful craftsmanship. Since this was such a long span of Chinese history, Hanfu, the traditional dress of Han era China, has a large amount of variation and a wide collection of garment types within its definition. Some of these garments were gendered, and some could be worn by either sex. Evolving fashions did change some of the details of these garments, but overall Hanfu clothing is characterized by its layering of separate tops and bottoms, wide sleeves, crossed-collars, the use of ties and laces for closures, and the flat cutting of material for the garments (Wang, “From Niche Interest to Fashion Trend”).

One type of Hanfu is the Ruqun, which consists of a short jacket called a ru, and a high waisted skirt. We can see an example of this is Figure 1, a wall painting from the Liao dynasty. Here we can see several women depicted wearing ru jackets with their crossed collars, tucked into high waisted skirts, and paired with Yaoqun, or short knee-length overskirts. Since Hanfu is from such an early era of Chinese history, it can be very difficult to find extant garments from the earlier dynasties that survive in the material record. Because of this, wall paintings such as this are often our best way of understanding clothing of a given era. We can still see how clothes were worn, and get a sense for the different types of garments. However, when we can find extant examples, they can offer even more valuable information about construction and materiality.

A slightly later example of Hanfu is Figure 2, an extant Aoqun from the Ming Dynasty. This is another variation of women’s dress. Similarly to the Ruqun, it consists of a separate jacket and skirt, however the Ao jacket of the Aoqun is slightly longer and made to be worn untucked, covering the waistband of the pleated skirt. In this particular example, we can once again see the crossed-collar that is characteristic of Hanfu, as well as the Pipa style sleeves with their curved shape. Because this is an extant, we can also see small details like the ties on the side of the jacket used as a closure. This garment is made of silk, which was valued not only for its beautiful sheen and soft texture, but was also very practical as a textile for daily wear because it can help insulate in colder weather, while also breathing well in warmer weather.

Just like much of Han art and culture, Hanfu was highly admired and ended up influencing many nearby nations. In particular, you can see many elements of Hanfu that were adopted into the traditional dress of Korea and Japan. To an untrained eye, Hanfu can be confused with Korean Hanbok and Japanese Kimono, given that they share the crossed-collar, use of ties and laces, layering of jackets and skirts, and the flat-cutting techniques used in their construction (Wang, “From Niche Interest to Fashion Trend”). This shows how Hanfu was used by the Chinese as a symbol for their national unity and prosperity. Nearby countries aimed to emulate it in an attempt to build connection to such a powerful nation. In this way, Hanfu is an example of how clothes can become a symbol of cultural unity and strength.

Manfu

During the Qing Dynasty, the Manchu people of northern China rose to power and became the ruling ethnic group of China. The Manchu were in the ethnic minority, and were a nomadic people from outside central China. In order to enforce their rule, they utilized changes and regulations of traditional dress to try and shift the alliances of the Chinese people to be in line with their own ethnic group.

Figure 3 is an example of Manfu, or Manchu traditional dress. Manfu differs from Hanfu in its less layered outfit composition, and use of more long robes, worn over pants. The crossed-collars have also changed to have a more rounded shape, and the large flowing sleeves of Hanfu have now narrowed down, and feature the “horseshoe” style Manchu cuffs. Manfu was even more androgynous than Hanfu. While garments were still loosely gendered, there was less visual distinction between the long robes and trousers worn by men, and those worn by women. These clothes also display evidence of sartorial influence from the nomadic lifestyle of the Manchu people. Manfu robes often featured front and side slits, visible In Figure 3, which were originally made to allow for easier horseback riding. The wearing of trousers was also something influenced by the nomadic lifestyle, given that they would have been very practical and also more comfortable for horseback riding. (Bulag, “Wearing ethnic identity: Power of dress”)

This change in dress was not always received positively by the Chinese people. The Manchu tried to regulate clothing, but this was more or less effective, and often was received with great pushback by the general populace. One of the changes they tried to enforce was the banning of foot binding, a practice done by the Han people to shape women’s feet as they grew so they would stay small and in line with Han beauty standards. It would have been more difficult for women with bound feet to walk around and engage in daily activities, given that their feet were so small and contorted by the bindings they wore. Manchu women on the other hand, wore long flat shoes with wooden platforms and did not bind their feet. While some women stopped foot binding during the Qing era, many still clung to this long lasting Han tradition, and would continue to foot bind well into the 20th century.

In general, some of the more successful clothing regulations were those for men and aristocratic court dress. Manfu quickly took over as the court dress of the Qing dynasty, and men were forced to start wearing their hair in the Manchu style, where they shaved their foreheads and pulled the rest of their hair back into a queue or braid at the back of the head. While men’s regulations were more effective, mainly because they were more heavily enforced, many men protested the wearing of their hair in the Manfu style since it went against Confucian ideals of never mutilating the body. Cutting or shaving hair was seen as bodily mutilation, but eventually the Manfu style did take over across China. Overall, women had a lot more sartorial freedom in the Qing era, particularly due to the fact that their dress codes were less effective and less heavily regulated, as well as because their compliance with those regulations was not seen as being as important as men’s. Many women, particularly those who were not part of the court or who lived in villages on the periphery of China, could continue wearing their own ethnic dress or Hanfu with little to no repercussions (Bulag, “Wearing ethnic identity: Power of dress”).

Qipao

Another well known type of Chinese traditional dress is the Qipao, also known by its Cantonese name Cheongsam. The origin of the Qipao is a bit contested. Many scholars simply assume that it evolved from a long Manfu robe. Antonia Finnane, however, takes a closer look into the garments origins, and expresses her opinions on its development in her book Changing Clothes in China : Fashion, History, Nation. She believes that the garment may have actually come from the May Fourth style of clothing, from the early 20th century. This style of dress consisted of a short jacket and short wide leg pants. Some early photographs of women wearing Qipao vs. trousers and blouses, show that the silhouettes of the two are very similar to each other (Finnane, Changing Clothes in China, 141-145). Fiannane’s analysis of contemporary Chinese clothing is very in-depth, and covers a lot of the political nuance of many sartorial changes. She examines many other micro eras of Chinese fashion, but our analysis will focus on the main points of interest so as to cover a more overarching timeline.

Another thing that makes Qipao distinctive is the impact on westernization on its design. It shares the androgyny, rising hemlines, and figure-revealing qualities of western dress of the 1920s and 30s. Qipao designs also often implement the use of western materials, especially lace trim decorations along the hem and neckline (Finnane, Changing Clothes in China, 109). Both of these elements are visible in figure 4, an illustration from a Shanghai fashion catalog from 1928. The dresses here are not dissimilar from the classic “flapper” silhouette of the 1920s, and implement decoration concentrated around the necklines and hems. Shanghai was the fashion capital of China at the time, and saw a huge increase in textile production with a focus on silk lace production (Finnane, Changing Clothes in China, 110).

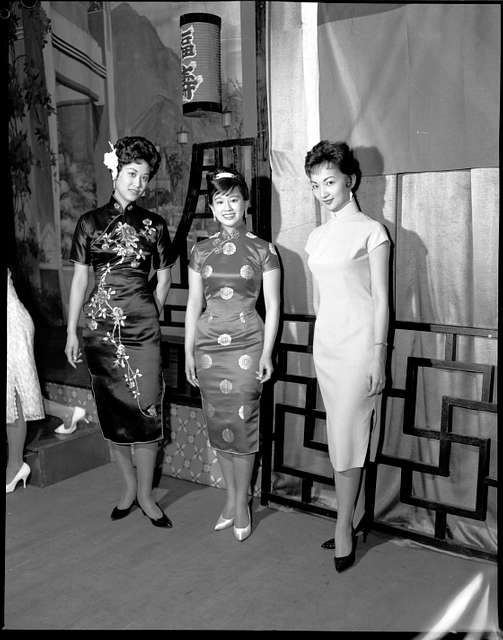

As Qipao evolved, the silhouette became more and more figure hugging, which sparked many debates on women’s fashion and what was acceptable dress. Figure 5 shows a later version of Qipao, worn by a group of women in the 1960s. We can see here that the shape has tightened, and shifted from the straight androgynous shape of the 1920s, into a much more hourglass shaped garment. This, along with the rising cut of the slit higher up the thigh, and discussion on whether to wear more western undergarments or to continue to bind down breasts in the traditional Chinese fashion, became the subject of many arguments for regulation of women’s clothing. Overall, there was no consensus in opinions, but instead there seemed to be a good amount of push and pull between movements for natural feet and unbound breast, vs. traditional foot and breast binding. All of this amounted to an era of both self-expression, and sexualization of Chinese women. Qipao offered more freedom, movement, and expression of sexuality for Chinese women, but this came along with political degradation, comedic satire, and Orientalism (Finnane, Changing Clothes in China). Overall, while this garment is often the first image to come into someone’s mind when they think of traditional Chinese dress, its history is very tangled and problematic, and its origins far more contemporary and western influenced than many people realize.

Contemporary Hanfu

After the cultural revolution, China lost a lot of its sense of identity, particularly where it related to traditional dress. During that time there was a movement to wear more masculine, uniform style clothing, which meant that many past cultural and historical modes of dress were tossed aside and forgotten in order to establish political conformity (Bulag, “Wearing ethnic identity: Power of dress,” 4). Now, Chinese people are at a loss of what constitutes their “traditional dress.” Because of this, many young people have started to dig into the past and revive Hanfu. An article by Xinyi Wang, François Colbert, and Renaud Legoux, titled “From Niche Interest to Fashion Trend: Hanfu Clothing as a Rising Industry in China,” discusses this resurgence, and some of the issues it faces. They offer both an outline of historical Hanfu, as well as an examination of how contemporary Hanfu communities are run and their ideals. It also discusses the impact of e-commerce and internet trends on the take off of contemporary Hanfu. However, I’d like to focus on the community aspect of the dress, and how it is being received by the general public.

Many young people in China have started to bring back the wearing of Hanfu in both everyday life, and for special occasions such as festivals and weddings. Figure 6 shows a large group of people wearing contemporary Hanfu during a convention. There’s also been a rise of Hanfu communities online, and people posting photos in Hanfu on social media. This has helped establish a new style of traditional dress, and a new way for Chinese people to express their culture and history through clothing. The new found interest has also pushed for deeper research and understanding of Hanfu fashion, which has allowed the discipline of fashion history to develop a deeper understanding of early Chinese fashion. However, since Hanfu is a style from such early years of China’s history, it can be very difficult to study given that the amount of surviving garments is small, and usually only from the later periods like the Ming dynasty. This has led to many debates among the Hanfu community on what is or isn’t authentic Hanfu, and if reproduction dress from earlier periods can be considered accurate given they are based on textual evidence or visual depiction instead of material culture. Sometimes this can cause rifts in the community, with gatekeeping of Hanfu to those who don’t maintain a certain standard set by some of the more picky members of a group. However, it does seem like there is a fair amount of push to be more educational than critical, allowing for deeper conversations instead of just dismissing someone for wearing something that is “incorrect.” (Wang, “From Niche Interest to Fashion Trend,” 85-87)

Another issue faced by the Hanfu community is the cost prohibitive aspect of obtaining accurate dress recreations. Because the aesthetic of Hanfu has become trending online, there is an influx of cheaply manufactured dress reproductions that do not take the same care in accurate recreation as smaller companies. However, those products can still be very popular because they are more affordable and accessible to those just starting out. This though can create issues where uninformed consumers develop an inaccurate understanding of Hanfu. That’s why many online communities work hard to curate the content they post about, and properly describe accurate Hanfu and where to get it so newer members can participate more fully (Wang, “From Niche Interest to Fashion Trend”).

Conclusion

Comparing all these era’s of Chinese history and the clothing that came along with them, we can see how dress was used to enforce political power or gender hierarchies, and control various ethnic groups. Clothing can be very divisive, separating “us” from “them.” It is a visual language just like any other. However, we have also seen how clothing can unite. It can bind a country together, crossing boundaries of ethnicity, power, and gender. Even today we see Chinese dress being shaped by the modern age and the connectivity of the internet. China is a vast and ethnically diverse nation, with a complex political history, which can make it hard to find commonality across the nation. Despite all that, dress gives us identity. It is so inherently tied to daily life, we all get dressed every day, and so if often one of the best lenses through which to examine the experiences of a society and its individuals.

Bibliography

Bulag, Uradyn E. “Wearing ethnic identity: Power of dress.” Berg encyclopedia of world dress and fashion 6, (2010).

Finnane, Antonia. Changing Clothes in China : Fashion, History, Nation. New York: Columbia University Press, 2008.

Wang, Xinyi, François Colbert, and Renaud Legoux. “From Niche Interest to Fashion Trend: Hanfu Clothing as a Rising Industry in China.” International Journal of Arts Management 23, no. 1 (2020): 79-89.