What is a fearsome protector?

A fearsome protector deity embodies a formidable force, a divine presence revered for its power to shield and defend. Often depicted with imposing stature and fierce countenance, these deities command respect and instill awe in believers. Their ferocity is not merely for intimidation but serves a crucial role in safeguarding devotees from malevolent forces and guiding them through trials. They are guardians of sacred realms, vigilant against threats both physical and spiritual. Yet, amidst their fearsome visage lies a benevolent purpose, for they are not only warriors but also nurturers of the righteous and champions of justice. In their fierce protection, believers find solace, knowing that in the face of adversity, they are not alone.

Aizen-Myōō, Wisdom King of Passion

Hanging scroll, ink, color, gold on silk

Artist unknown

H. 102cm, W 60.5cm

2017.101 (CMA)

Image courtesy of The Cleveland Museum of Art, Open Artstor

Aizen-Myōō, the Wisdom King of Passion is depicted here seated on a lotus throne, silks and jewels adorning his blood-red body. His lion sits upon his head, ready to devour the desires of those who pray to him.

Vajrabhairava, Tantric Form of the Bodhisattva Manjushri

Embroidery in silk, metallic thread, and horsehair on silk satin

Artist unknown

57 1/2 x 30 in. (146.1 x 76.2 cm)

1993.15 (MET)

Image courtesy of The MET’s Open Access policy

Vajrabhairava is a form of Yamantaka. The buffalo headed deity Vajrabhairava frightens away egotism and selfishness. Here, each one of his 7 heads wears a crown of 5 skulls.

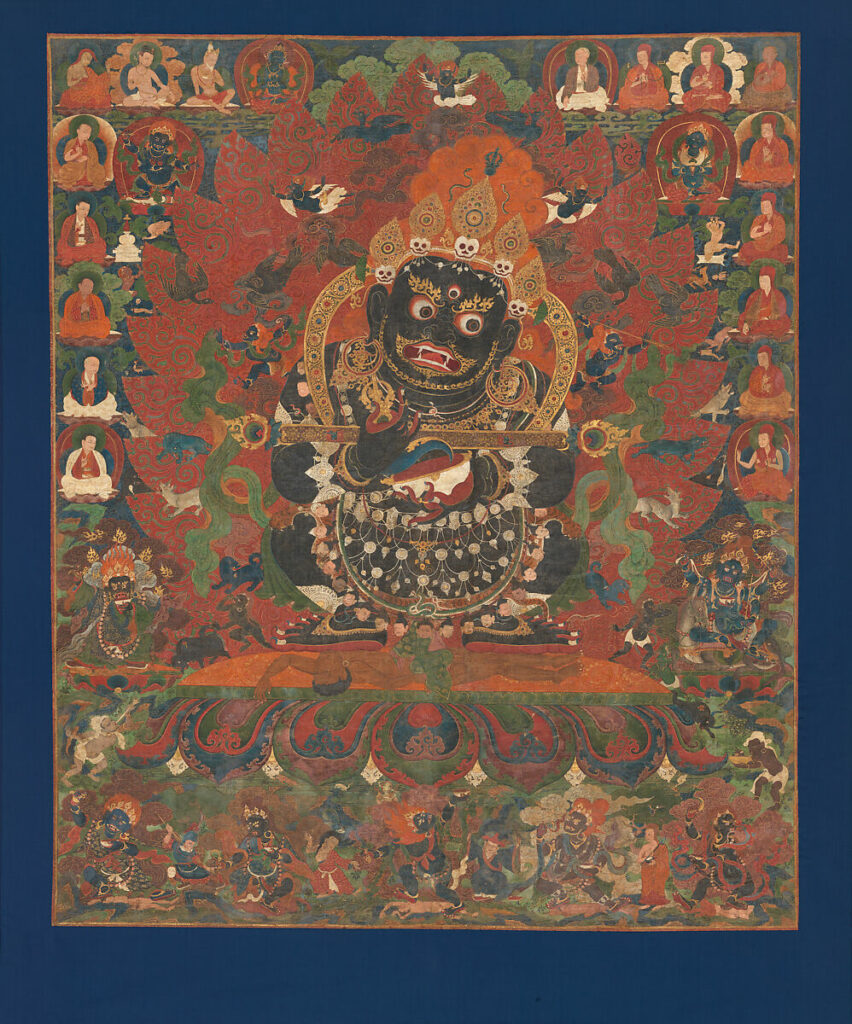

Mahakala, Protector of the Tent

Distemper on cloth

H. 64 in. (162.6 cm); W. 53 in. (134.6 cm)

Artist unknown

Central Tibet

2012.444.4 (MET)

Image courtesy of The MET’s Open Access policy

Here, Mahakala stomps on a corpse while wielding a knife meant for cooking. Mahakala protects his monks from spiritual ignorance, slicing through negativity with his knife.

Chamunda, the Horrific Destroyer of Evil

Sandstone

H. 44 1/2 in. (113 cm)

Artist unknown

1989.121 (MET)

Image courtesy of The MET’s Open Access policy

Chamunda is a dark form of the goddess Chandi, the Hindu Mother Goddess. This would have decorated the outside of a temple, scaring off potential wrong-doers. Here, she poses battle ready, her arms (now lost) most likely holding a litany of weapons.

Moving on from Buddhism, the next example is Chamunda. Chamunda is a violent, destructive form of the Hindu mother goddess Chandi. Her domain is war, epidemics, famines, natural and man-made disasters. She is an attendant of the warrior goddess Parvati, and is heavily associated with the goddess Kali.

While not painted in the sculpture shown, most likely due to weathering over time, Chamunda is usually shown with black or red skin. Broken off of this statue from age or travel, her many arms would hold an assortment of items- a Damaru drum, trishula, a diamond thunderbolt, and all assortments of knives, swords, and weapons made out of skulls. She is frequently shown flanked by evil spirits, who swarm her fallen enemies- they dance at her feet and eat their corpses, rejoicing in Chamunda’s wrath. She is often adorned with snakes, who curl around her garland of severed heads, and into her crown of matted hair and bones.

While the other deities would have very directly been associated with protection, Chamunda is almost always only associated with destruction. She is, after all, a gruesome figure to behold- her bulging eyes, full of fire, gaunt, skeletal body and bared tusks spark fear in the hearts of all. What classifies her as a fearsome protector is how her power is invoked. After all, the best defense is a good offense. Though there is limited information about where exactly the icons of Chamunda are placed, this particular statue was outside the temple. This, along with some photographs of other temples dedicated to Chamunda, appear to establish her as a form of gatekeeper. She is invoked as a ward, like a skull and crossbones label on a bottle. Simply put, to trespass on temples where Chamunda’s icons reside is to trespass on Chamunda- and good luck surviving that. It is a threat, a promise of a slow, agonizing end to would-be wrong-doers that try to close in on the temple. This is protection- perhaps not the direct, passionate affection we see for people, but a gift provided to her devout, should they prove faithful to her.

Pazuzu, King of the Wind Demons

Bronze figurine

H. 15cm, W. 8.6cm, D. 5.6cm

Artist unknown

MNB 467 (Louvre)

Image courtesy of The Louvre’s Terms of Use, Article 4.1

Copper statue of the Wind Demon King, Pazuzu. Here, he is shown with 4 splayed wings, horns, a dog-like jaw, and other animal features blended into his semi-human form. He also has a fully erect penis.

Pazuzu’s claim to fame is that he is more evil than his nemesis, Lamashtu. While it may be dangerous for a mother to invoke the power of Pazuzu, for fear of the demon’s wrath turning on her or her, Pazuzu simply hates Lamashtu so much that he will flat out ignore the mother and children in order to tussle with the lion-faced demoness. Why, on god’s green earth, would this be of any use to the person praying to Pazuzu? Well, it just so happens that Lamashtu is the demon that is invoked to bring harm to pregnant women, mothers, and children and is one of the most powerful malevolent forces in ancient Mesopotamian religion.

One of the reasons Pazuzu’s likeness is so well documented is because he is commonly depicted as small charms, pendants, and statuettes, like the statuette shown above. Physical images of deities, whether they be spirits, gods, or demons, were thought to attract the attention of the being displayed. It is important to note that these depictions are usually small- while Pazuzu was a household name, his power was not something to be taken lightly or invoked flippantly. With a flap of a wing, he could level a city with a thunderstorm or great flood. A wave of a hand could bring a swarm of locust upon a town. A murmured order could rally every single wind demon against his foes. To create a gargantuan statue of Pazuzu is to invite his gargantuan might- thus devastating whoever had the gall to attempt to invoke that much power.

Unifying Characteristics

- Animal aspects

- Tiger head companion, buffalo head, scorpion naval and snake jewlery, dog snout, horns, wings

- sAssociations with wisdom

- Protectors of wisdom, removing worldly dangers

- Otherwordly skin tones

- Red, blue, black, gray, green

- Violence as a means to an end

- Not seeking out violence, but being able to properly retaliate if and when the time comes

Bibliography

“Aizen Myōō / 愛染明王像.” n.d. https://jstor.org/stable/community.24628684. Barbre, Claude. 2012. “Art: DEMONIC DIVINE: HIMALAYAN ART AND BEYOND,” Journal of Religion and Health 51, 51 (1). Springer: 231–34. http://www.jstor.org/stable/41349880. Cunningham, Michael R. 1993. “Fierce Salvation: Comments on a Recently Acquired Japanese Sculpture,” The Bulletin of the Cleveland Museum of Art 80, 80 (4). Cleveland Museum of Art: 140–43. http://www.jstor.org/stable/25161402. Dalton, Jacob P. 2011. Evil and Ignorance in Tantric Buddhism. The Taming of the Demons. Yale University Press. http://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt5vkw2s.5. FAURE, BERNARD. 2022a. Front Matter. Rage and Ravage. University of Hawai’i Press. doi:10.2307/j.ctv1k3np30.1. ———. 2022b. Front Matter. Rage and Ravage. University of Hawai’i Press. doi:10.2307/j.ctv1k3np30.1. Goepper, Roger. 1993. “Aizen-Myōō: The Esoteric King of Lust: An Iconological Study,” Artibus Asiae.Supplementum 39, 39. Artibus Asiae Publishers: 3–172. doi:10.2307/1522701. Hirasawa, Caroline. 2008. “The Inflatable, Collapsible Kingdom of Retribution: A Primer on Japanese Hell Imagery and Imagination,” Monumenta Nipponica 63, 63 (1). Sophia University: 1–50. http://www.jstor.org/stable/20535182. Moorey, P. R. S. 1965. “A Bronze ‘Pazuzu’ Statuette from Egypt,” Iraq 27, 27 (1). British Institute for the Study of Iraq: 33–41. doi:10.2307/4199778. Rahmouni, Aicha, and Baruch A. Levine. 2016. “Deities Who ‘Turn Back’ from Anger,” Journal of the American Oriental Society 136, 136 (2). American Oriental Society: 235–45. doi:10.7817/jameroriesoci.136.2.235. Saggs, H. W. F. 1959. “Pazuzu,” Archiv für Orientforschung 19, 19. Archiv für Orientforschung (AfO)/Institut für Orientalistik: 123–27. http://www.jstor.org/stable/41637103. Unknown. 911–604BC. Pazuzu, Mesopotamian Demon Guardian of Children and Pregnant Women . Bronze Figurine. Paris: Lourve. https://collections.louvre.fr/en/ark:/53355/cl010120489#. ———. Early 15th Century. The Deity Vajrabhairava, Tantric Form of the Bodhisattva Manjushri. Embroidery in silk, metallic thread, and horsehair on silk satin. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art. https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/39742. ———. 1200. Chamunda, the Horrific Destroyer of Evil. Sandstone. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art. https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/38152. ———. 1500. Mahakala, Protector of the Tent . Distemper on cloth. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art. https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/78195.