Art is a powerful tool and a dangerous weapon. It gives voice to experiential truth, shaped by the social reality of a political landscape. Yet, how does one qualify the authenticity of artistic expression? According to Chinese contemporary artist and activist Ai Weiwei, “if [the art and literature of that society] is not questioning that authority, it’s a fake,” (Schindhelm 2016, 1:25:46). We can gauge the value of artistic messages, not by their general affect or critical reception, but by looking at how the means of self-expression are controlled and purged by the state. The official reaction and preemptive measures against art confirms its presence to be a threat to prevailing power structures.

While social resistance to authoritarian censorship is not terribly unique to China, per se, its effects linger in the cultural memory of those who witnessed the country’s historic transition into a modern superpower. The developments within the last fifty years have been instrumental to the emergence of the Global East, of which China is no exception.

One man who lived through this dynamic period is Dr. Uli Sigg, a Swiss expatriate and businessman. Following Chairman Mao’s death in 1976, new economic reform permitted a deregulation of trade policies through capitalist intervention. Coming to China in 1979, Sigg participated in the county’s rapid industrialization effort by building factories and selling elevators on behalf of the Schindler Group. His work involved extensive communication with PRC officials, including communist leader Deng Xiaoping. Schindler’s enterprise, headed by Sigg, became the first joint venture between the People’s Republic and any Western Company, creating an exemplary model for international trade between the world and China. After the Tiananmen incident in 1989, Sigg and his western colleagues opted to stay in China, citing professional responsibility and cooperation despite the country’s global unpopularity.

In 1995, Sigg was appointed Swiss ambassador to China, Mongolia, and North Korea. This new role allowed him to meet artists and purchase their works with less personal risk. His diplomatic duty required him to host many official visits to the consulate, where works from the Zürich school of Concrete art were on display. Sigg took notice of the reductive attitudes held by Chinese guests towards this style modern art, received with a general incomprehension of its abstract principles. “I actually wanted to bring in Chinese contemporary art,” notes Sigg, who “naturally knew that the Chinese didn’t know their own contemporary art, and definitely not the prominent Chinese,” (Schindhelm 2016, 0:45:54). After removing all the Swiss art, Sigg used the Beijing Embassy to showcase his growing collection of work produced in China. This exposure created new interest among influential figures in the art world, to whom these modern pieces would otherwise be inaccessible. An increased recognition for Chinese contemporary artists vitalized their working practices, taking their art from an underground movement to the international stage. Curator and critic Hans Ulrich Obrist describes a fantasy of sleeping overnight in a museum, being fulfilled by his time spent in Beijing, emphasizing that: “the Swiss embassy was an incredible museum, the first museum for contemporary art [in China],” (Schindhelm 2016, 0:52:18). While the last part is not necessarily true, it was probably the longest ‘museum’ of its kind to survive the wrath of censorship. Sigg’s amateur yet strategic curatorial skills birthed a demand for art generally unknown to most Chinese at the time.

My analysis is largely informed by two main sources. The hypertextual inspiration for my focused study, also the source for my eponymic title, is Michael Schindhelm’s documentary The Chinese Lives of Uli Sigg (2016). I refer to this article extensively, as it contains many valuable interviews with, besides Sigg himself, the artists whose personal relationships transcend the transactional nature of collecting. I will further explore Sigg’s intentions later, but it is imperative to acknowledge the intrinsic bias cultivated by the controlling of perspective through filmmaking. The other source is an article by Sheldon Hsiao-peng Lu, a Professor of Comparative Literature at the University of California, Davis. His literature review, ‘Art, Culture, and Cultural Criticism in Post-New China’ (1995), advances the understanding of the artistic movements Sigg collected. By using the scholarship of Chinese critics and historians Lu contextualizes the specific language used to interpret avant-garde as a particularized aesthetic of modern and post-modernity. Visualized concepts like cynical realism “(washi xianshi zhuyi)” and political pop “(zhenzhi bopu)” serve locally unique styles better than Western associations to those words (Lu 1997, 115). I’ve included other, ancillary texts that with strengthen my exposition on the avant-garde, contemporary art of China.

To understand the current iteration of Chinese contemporary art, it is necessary to look at the social context that shaped it. Strict regulations to limit artistic expression predated Mao’s regime and the Cultural Revolution. Before taking power in 1949, the Yan’an-based CCP laid out the principles of a single-minded aesthetic movement where, for art to be canonized, every work must be part of the Communist struggle. This severely limited what could be represented in art. Every piece was subject to the Party’s aesthetic and symbolic criteria, whose content was closely measured and surveilled. “And the Communists had a very clear idea; they said they gain the power by the gun and maintain stability by the pen—that means writing and art and self-expression and the media are always being censored or controlled,” (Ai and Cohen 2016, 156). Censorship, including the suppression and expulsion of the dissident intellectual class, is a form of propaganda and a powerful means of securing civil stability. Authoritative omission of all criticism cultivated the environment of excruciating self-surveillance and sacrifice many associate with Mao’s rule.

The Cultural Revolution, while cursing self-expression, raised its authority to monolithic status. As the Red Guard pillaged historical sites and banished tradition from the Chinese cultural imagination, new art flooded into the politicized sphere of public imagery. After the People’s Republic seized leadership of educational institutions, these images were restricted to a few thematic subjects, mainly: the proletariat struggle, communist utopia, and reverence for Mao Zedong. These representations placed the Party’s interest above all else, shrinking visual culture to a singular politicized artform. A former propagandist for the Nationalist Party, Chairman Mao understood how dissenting opinions and imagery could destabilize his national influence. Before he took power, his 1942 speech at the Yan’an Forum on Literature and Art became a formative blueprint for the CCP’s restrictions on free speech stating that, “The goal of art is to ‘awaken the masses, fire them with enthusiasm, and impel them to unite and struggle to transform their environment,’” (Thorp 2001, 394). Though his language is positive, there is no room in his conception of material culture for messages that do not serve the regime, disguised here as the ‘masses.’ His radical of Lenin’s Antagonistic Contradiction and an absolute and universal concept hardened an ideology that demanded political conformity. Thus, a flattening of identity for the sake of a unified national ego was imposed on the masses for the collective good.

An understanding of Maoist irreconcilability of class struggle frames the prevalent attitudes of the Cultural Revolution. The forms and styles of aestheticized tradition were appropriately reevaluated and dismantled as an iconoclastic gesture against the ruling class: a group presumably responsible for the maintenance of Chinese cultural identity for hundreds, if not thousands of years. Members of the landed gentry and intellectual elite, which included artists, were systematically exiled or executed by the CCP (Weiwei and Cohen 2016, 156). Impassioned citizens would resort to mob justice to inflict punishment on the surviving remnants of landowning families, as was the youth experience of Fang Lijun (b. 1963), who describes having stones thrown through his family’s windows while they were asleep (Schindhelm 2016, 0:21:55). This extreme state of Chinese society would reverberate through the works of the artists growing up under Maoist control.

Deciding to collect pieces after the Cultural Revolution, Uli Sigg aimed to document the changing atmosphere in China following Mao Zedong’s death. Chinese historians would consider this period the post-Mao “New Era…that begins with the Reform in the late 70s,” (Lu 1997, 122). Corresponding with Sigg’s introduction to China, Feng Guodong (b. 1948) painted River of Light1. Feng’s command of texture over the scene affects a haptic topology of light and color. These elements are integrated into an overlapping flow of form that comprise the vertical riverscape. Its fauvish palette is saturated with muted tones. The dotted particles and rhythmic waves covey the piece’s movement, containing the energy diffused across the composition and stretching off the canvas. A temporal pulse is felt throughout the structural dynamism. I like this piece a lot.

Trained in the manner of symbolist painting, River of Light is one of Feng’s last representational artworks before he shifted focus to purely abstract subjects. While his painting is beautiful, it is impossible not to apply a subtextual reading while mentally unwrapping the visible layers. A member of Stars group, Feng exhibited work at the infamous popup outside the National Art Museum of China in Beijing that same year. With his activism in the background, the historical reality River of Light captures is radically self-expressive. For me, there is a dyadic metaphor that capitalizes on seemingly disparate, yet complementary emotions: First of which is blissful sunlight gently sprinkled into the current, like joyful tears shed in celebration of Mao’s eternal exit. The other, more sinister reading looks at the red hues of the river and the sun’s oppressive glare, suggesting that Mao’s legacy will persist while the blood of millions continues to rush. This analogy is extremely likely when considering the multiple comparisons his delegate companions and personal friends made while visiting his hometown, such as: “Like the sun, [Chairman Mao] belongs to all mankind,” (Huan 1966). However, I think both interpretations are valid, and the fact they are achieved concurrently through Feng’s work is a testament to the subjective power he wields. The deification of Mao was a political tool to obfuscate the very real institutional abuse that is expressed in the artworks of the New Era.

Sigg’s first collected artwork was a large-scale propaganda painting hung from the ceiling of a Shanghai factory. He first noticed the piece in 1979 and returned to Switzerland with it ten years later, as a wedding present for his wife, Rita. Propaganda continued to dominate and inform the cultural sphere of public life, yet after the western economy became more involved in China the lives of its citizens had a new flavor. In the documentary, Sigg describes how, in the eighties, the first entrepreneurs began to spring with the growth of national commercialism. In the streets of say Beijing, one could see people repairing bikes or families operating restaurants. This new attitude towards growth was transformative, and yet artistic advancement staggered without the cultural foundation that was undone by the early PRC. Shao Fan’s (b. 1968) diagnosis of the Western influence on China’s cultural awareness uses a striking metaphor:

“Modern artists in China know the history of Western art better than they do traditional Chinese culture. Typical Chinese things vanish. Because Chinese culture is weak nowadays. Western culture forms the mainstream. If we compare both cultures to water, Western culture is like rain in China today. Whether we like it or not, if we go outside we get soaked by this rain. Chinese culture is more like groundwater,” (Schindhelm 2016, 1:11:10).

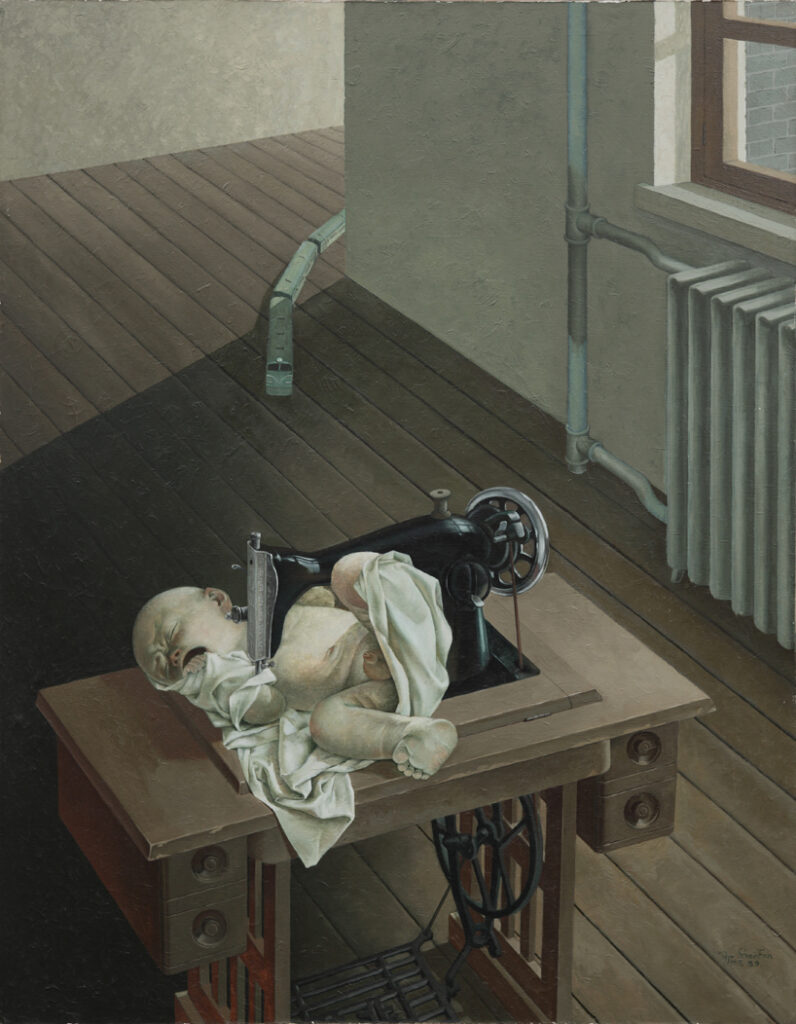

Shao Fan (b. 1964) is one of China’s most globally celebrated painters. While his practice extends into other design mediums, his visual art engages an extended dialogue with his country’s artistic history, reflexively opposed to Western practices and methodological perspective. Shao was born into an old family of renowned Beijing artists. His style is deeply intrenched in a native philosophy, which attempts to restore a challenged cultural identity. These words apply more to his series of animals than the brutally conscious example I’ve chosen. The Cradle2 is the only piece in my article that is not in the M+ Sigg collection. Although it appears in his collection, where it is currently held remains elusive. Appearing in his show, An Incurable Classicist (2010), the image is a horrific indictment of China’s adoption of late capitalism and global overconsumption. The symbolic content of this piece is densely overwhelming, yet the composition empties out to enhance our focus on the foreground. Depicted is an infant on a sewing desk being stitched into a cloth. Shao exerts incredible control over the elements around the subject: lighting perspective, and the construction of the grimly bare scene. Through expert use of classically western realist principles, he creates a statement with the style. The surrealist ambience is directly related to the same movement in European modernism, concretized through the train imagery. Western avant-garde paintings used train imagery in homage to futurist ideologies. A prominent example of this can be found in René Magritte’s La durée poignardée (Time Transfixed) (1938). Shao also employs signature visual themes that explore literati and Song-dynasty modes of thought.

As technology became more readily accessible, artists working outside traditional mediums could experiment with production techniques. Photographer Li Wen used the camera to stage his performance art. His piece Cut in Half3 places a seated row of people in front of a developing cityscape. On the right half, the men are coated in some sort of plaster while the women opposite to them are not. The subject sitting center is the odd one, as he is covered only on one side and aligned with the building behind him. There is a humor repressed by the subject’s expressions, or lack thereof. A considerably impressive effort, the image pays off visually and metaphysically. Daoist symbolism can be interpreted through the gendered organization and opposing colors representing yin and yang. The central figure could be read, then, to be analogous to everyone, including the viewer, that exists in unique balance of spiritual harmony.

The immediate historical context that pairs with all works after 1989 is the June 4th Tiananmen Square incident that signifies the end of New Era China. The post-New Era describes what I’ve already covered regarding new consumerism in the wake of the failed communist experiment. In addition to this, there are new forms of mass media and information technologies. The onslaught of electronically transmitted messages and signals effectively dulled the critically conscious public discourse. Cynical Realism, considered one of the major categories of post-89 art by curator and critic Li Xianting, is, in Lu’s words, “a roguish, irreverent travesty of ‘revolutionary realism’ in the Mao era,” (Lu 1995, 115). ‘Revolutionary realism’ was just the PRC’s style of Social Realism. Inverting Mao’s doctrine that art is a constructed means towards a political end, Cynical realists subvert that practice by representing the fallout of post-Tiananmen society. Fang Lijun’s series of baldheaded figures exude a sense of listless idleness. His painting Untitled (Serie/Köpfe)4 makes the disorienting void of purpose an off-frame subject, implied by the crowd of figures looking up in some type of desperate plea. This existential despair is accented by the mass of heads that are almost indistinguishable. A uniform styling restricts their individuality, as their collective forms resemble a feature of landscape.

Another figure of the Cynical Realist movement is Yue Minjun’s (b. 1962) series of sculptures, entitled 2000 A.D.5 A similar uniformity to Fang’s work is present among these figures, whose exaggerated smiles are reflexive of a more dispiriting reality. The depoliticizing element really comes through their closed eyes, an effect multiplied by the repetition of their form. Regarding Chinese tradition, there is a clearly slanting reference to the Terracotta Army, whose conception and execution worked towards the political end of Emperor Qin’s immortality. Yue illustrates the national consciousness during the cultural shifts of the furthering transformations of 1990s economic reform. Both Yue and Fang’s figures are icons of passivity that pledge not to repeat the events of June 4th through active intervention, though they painfully resist forgetting.

In a September 2013 issue of ArtAsiaPacific magazine, Uli Sigg published his taxonomy of collecting styles, in which he identifies five types: I Like art, Investor, Status, Focused, and Web. Though Uli’s collection was borne from an innate love of art, the purpose of study prohibited overindulgence. The first three types of collecting are self-defining. ‘Focused’ collecting seeks to bind works of art to create additional meaning in each other’s presence. What makes this a disciplined practice is understanding how one’s reasoning must be aligned to the goal of advancing comprehension of the focused subject. The ‘Web’ style of collection is the evolution of ‘Focus,’ where works contextualize each other to great compliment. Uli elaborates in mentioning how, “‘Web’ collecting is just as much about finding the pieces which may go unattended, or ascribed to artists considered second tier at times—which in itself is subject to change over time—to fill the perception gaps, to narrate the underlying subtexts and to ultimately bring a collection to the fore,” (Sigg 2013). This, I believe, accurately summarizes Sigg’s idealized strategy in building his collection. Whether it was realized or not is subject to interpretation. Yet official consensus believes that an entire museum should be erected to house his collection, materialized as the M+ museum for visual art in Hong Kong. His 2005 exhibition Mahjong at the Bern Kunstmuseum was regarded by European critics and artists as the ‘Bible of Chinese Contemporary Art.’

Though, as important global exposure is for the artists, it is Chinese culture that stands to benefit the most. “I created the collection to bring it to China,” said Sigg (Schindhelm 2016, 1:14:46). The critical lens offered by abstract art strengthens cultural identity through historic awareness. Chinese avant-garde is a movement discontinuous with western modern art. It is a document of the country’s ahistorical arrival in modernity. Sigg consolidated the artworks stowed in attics and basements and preserved their existence in the face of possible extinction. The art itself has power, as described by Ai Weiwei: “What [the government is] afraid of is art having different levels of meaning, or even unclear or indescribable conditions, which they would consider [potentially] dangerous,” (Ai and Cohen 2016, 159). Chinese contemporary art is one of the most interesting genres of art, since it is characterized by a critical awareness of its conditions. Art that targets the state and its institutions, especially when doing so is strictly prohibited, is conceived by a resilient will for the survival of the human spirit.

Schindhelm, Michael. The Chinese Lives of Uli Sigg. Brooklyn, NY: Icarus Films, 2016. https://docuseek2.com/if-uli.

Weiwei, Ai, and Ethan Cohen. “A Conversation.” Social Research 83, no. 1 (2016): 155–63. http://www.jstor.org/stable/44283402

Sigg, Uli. “How People Collect.” ArtAsiaPacific, no. 85 (2013): 59–60. https://search.informit.org/doi/10.3316/informit.738298350113728.

Thorp, Robert L., and Richard Vinograd. 2001. Chinese Art & Culture: Robert L. Thorp and Richard Ellis Vinograd. New York: Harry N. Abrams.

Lu, Sheldon Hsiao-peng. “Art, Culture, and Cultural Criticism in Post-New China.” New Literary History 28, no. 1 (1997): 111–33. http://www.jstor.org/stable/20057404.

Huan, Chiu-Chih. “Chairman Mao Is the Red Sun in the Hearts of the People of the World.” Peking Review. July 22, 1966, Volume 9 edition, sec. #30.

Image Source in order:

- https://www.trouw.nl/nieuws/de-collectie-van-verzamelaar-uli-sigg-staat-bol-van-verrassende-chinese-kunst~bd52ed77/ (Cover Painting, Zhao Bandi)

- https://www.mplus.org.hk/en/collection/objects/river-of-light-20121/

- https://www.designboom.com/art/shao-fan-an-incurable-classicist/

- https://www.mplus.org.hk/en/collection/objects/untitled-2012558/

- https://www.mplus.org.hk/en/collection/objects/untitled-serie-kopfe-2012320/

- https://www.mplus.org.hk/en/collection/objects/2000-ad-group-of-sculptures-25-figures-20121320/