How did availability of resources and innovation impact artistic choice in ancient Asian Art?

and

How did cultural context and available resources impact artistic choice in ancient Asian Art? What does the future of Asian Art look like?

Pigments and artworks will be introduced to better elucidate the colorful history of the continent of Asia. It is important in our observation and analysis of artwork to remember that pigments and dyes had widespread use all over Asia, in attempts to bring more color to the understanding of historical art which has often been underestimated or forgotten. Oftentimes Asian art under observation from the western world is often watered down and simplified to the ancient manuscripts and artworks originating in East Asia, and the true scale of the continent as well as its rich history and cultural diversity is forgotten and untold. This disregard for the existence of other equally enthralling works from across the continent creates a grave mischaracterization of the history of Asian Art. Despite the difficulty in preservation of color and pigments on artifacts that are thousands of years old, the remnants of these colors take hold in the present cultivation of dyes and pigments, as they created traditions which may still be in use, or acted as the stepping stones for the creation of modern pigments which are now used globally. It is imperative that we, as scholars and researchers of today, give credit to our predecessors and acknowledge the effort and innovative methods of producing the pigments and dyes that make our past and present so colorful.

Han Purple

Han Blue and Han Purple, also known as Chinese Blue and Purple, are synthetic barium copper silicate pigments first discovered on artifacts from the Han Dynasty (206 BCE to 220 CE). These pigments were best known for their use as paint on the terracotta warriors, an army of ceramic soldiers created to guard the tomb of the first Chinese emperor. Despite being produced since 1050 BCE in Ancient China, the pigments deteriorated within seconds of being unearthed after more than 2,000 years. Han Blue shares similarities with Egyptian Blue, but the Chinese process involves an additional step using lead. It is believed that glass makers in Ancient China may have discovered these pigments while attempting to create a jade-like glass, a process that also involved the use of lead.

Kneeling Archer

Title: Kneeling Archer

Creator: Unknown

Material: Earthenware with traces of Pigments

Size: 48 in. (121.9 cm): W. 27 in. (68.6 cm); D.19 1/4 in. (48.9 cm); Wt. 304.2 lb. (138 kg)

Date: Qin Dynasty (221-206 BCE)

Culture/Location: China

Source: The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Credit: Lent by Emperor Qinshihuang’s Mausoleum Site Museum

Based on the figure’s gestures, we can assume he was an archer, although his crossbow is now lost. He is one of the few that still bears traces of color. Chemical analysis suggests the use of mineral pigments such as cinnabar, azurite, malachite, bone or lead white, and the artificially produced “Han Purple.”

Indian Yellow

Indian Yellow is a bright, deep-mustard pigment originating from India in the 15th century, noted for its intense luminance and best known for its use in Rajput-Mughal paintings from the 16th to 19th centuries. It made its way to the West in the 17th century through Calcutta merchants, where European artists loved its vivid yellow hue. Many famous artworks, including the stars of Van Gogh’s “Starry Night,” used Indian Yellow. The pigment was synthesized by feeding cows a strict diet of mango leaves and letting them urinate onto a special sand. Indian Yellow fell out of favor in the late 19th century, partly because an investigation found the cows’ diet to be very unhealthy and painful.

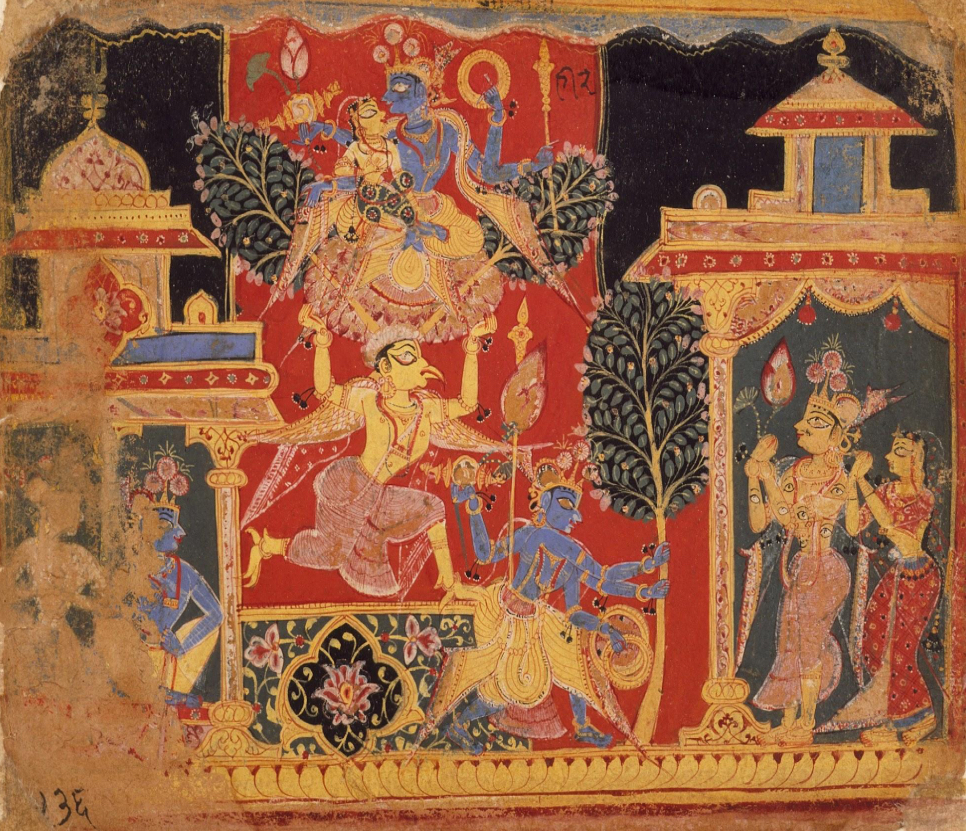

Krishna Uproots the Parajita Tree

India, Delhi-Agra region, possibly Mathura, circa 1520-1530

Creator: Unknown

Material: Opaque watercolor (including indian yellow) and ink on paper

Size: 7 x 9 1/2 in. (17.78 x 24.13 cm); Sheet: 7 1/4 x 9 1/2 in. (18.42 x 24.13 cm)

Source: Nasli and Alice Heeramaneck Collection, Museum Associates Purchase (M.72.1.26)

This depiction shows blue-skinned Krishna, the 8th incarnation of Vishnu, the god of preservation. Krishna, pictured as the four-armed Vishnu, uproots the celestial Parijaat tree from heaven and carries it to earth, upsetting heavenly deities. They feared that without a distinction between heaven and earth, people would stop worshipping immortals. Krishna was ultimately against any exclusive possession of wealth and resources.

Malachite Green

Malachite, a natural mineral and reliable source of pure pigment, is chemically a basic carbonate of copper and is abundant in Russia, Congo, and Chile. Known to the ancient Egyptians, who used it as eye-paint, malachite green became more prevalent in Japanese and Chinese paintings from the seventh century onwards. It was not commonly used in Europe due to the existing popularity of oil paint and because malachite, being a coarse mineral, became less vibrant when finely ground. However, it can serve as a permanent pigment in oil paintings, with little dulling and unaffected by light exposure.

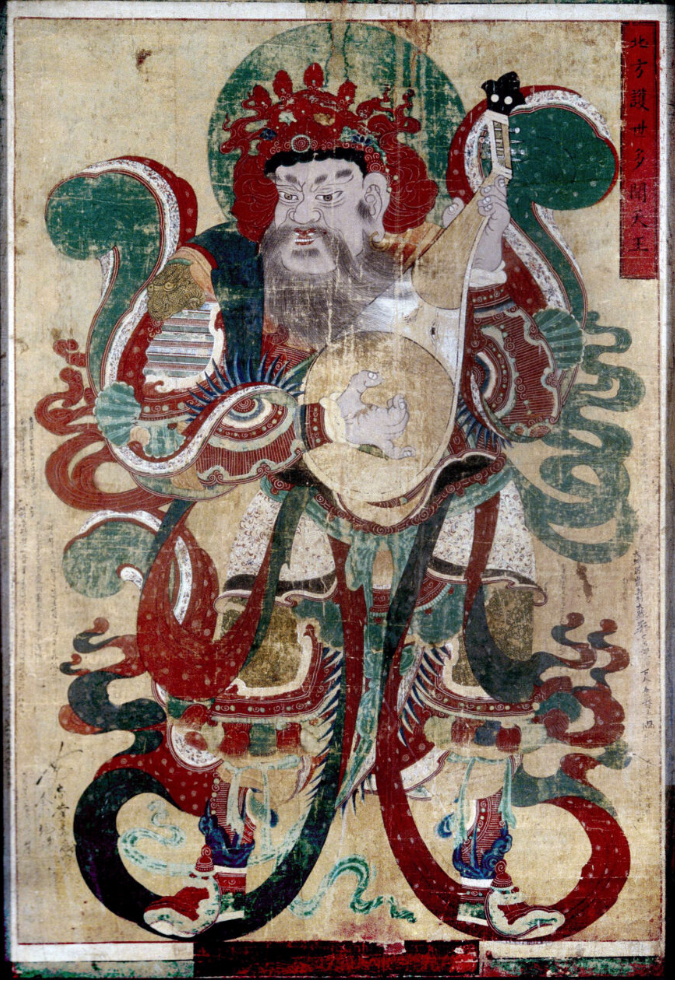

Dhratarastra, Guardian King of the East

Title: Dhratarastra, Guardian King of the East

Creator: Unknown.

Material: Paint on Hemp Cloth

Size: width: 207.00cm; height: 301.00cm

Date: 1796/1820 – Joseon Dynasty

Culture/Location: Korea

Source: Purchased from Yamanaka & Co

Credit: Trustees of the British Museum

This painting is from the late Choson period (1392-1910), when Buddhism became more active in government. The four guardians of direction (north, east, south, west) acted as defenders of Buddhism, and these protector images are found in painting and sculpture at temple entrances. The lute he carries is an attribute of Dhratarastra, the guardian king of the east. The huge canvas size, dynamic and decorative lines, and combination of mineral colors are typical of Korean Buddhist paintings, with malachite green being characteristic of 19th-century Korean Buddhist art.

Lapis Lazuli

The first known use of lapis lazuli as paint was found on two giant Buddha statues in Bamiyan, Afghanistan, more than 6,000 years ago. It was then exported along the Silk Road from the Sar-e-Sang valley in the Badakhshan mountains of Afghanistan. The gem, made from the complex salt mineral known as lazurite, appears in a range of colors from deep blue to purple to blue-green. Lapis lazuli has been found in countries such as Afghanistan, Chile, Siberia, Northern Myanmar, Baffin Island in Canada, and the western United States. Historically, besides its use as a pigment, it was used to make jewelry and as a mixture worn around the eyes to ward off infection. In the 13th and 14th centuries, lapis lazuli was often ground up to create a rich and deep ultramarine used by painters.

Crowned Buddha

Title: Crowned Buddha

Creator: Unknown

Material: Bronze inlaid with silver, lapis lazuli, and rock crystal

Size: H. 12 5/8 in. (32.1 cm); W. 7 1/8 in. (18.1 cm); D. 5 1/4 in. (13.3 cm); Wt. 7 lbs (7 lbs (3.2 kg)

Date: 10th–11th century Pala Period

Culture/Location: India (Bihar)

Source: The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Credit: Gift of Miriam and Ira D. Wallach Foundation, 1993

The crowned Buddha is seated touching the earth at the moment of his enlightenment. He is adorned with a crown and necklaces inlaid with silver, as well as silver-inlaid eyes and an urna (forehead dot). The interpretation of crowned Buddhas is much debated and varies among communities. The stepped throne he rests upon and the flaming mandorla are inlaid with lapis lazuli, although time has worn away most of the stones.

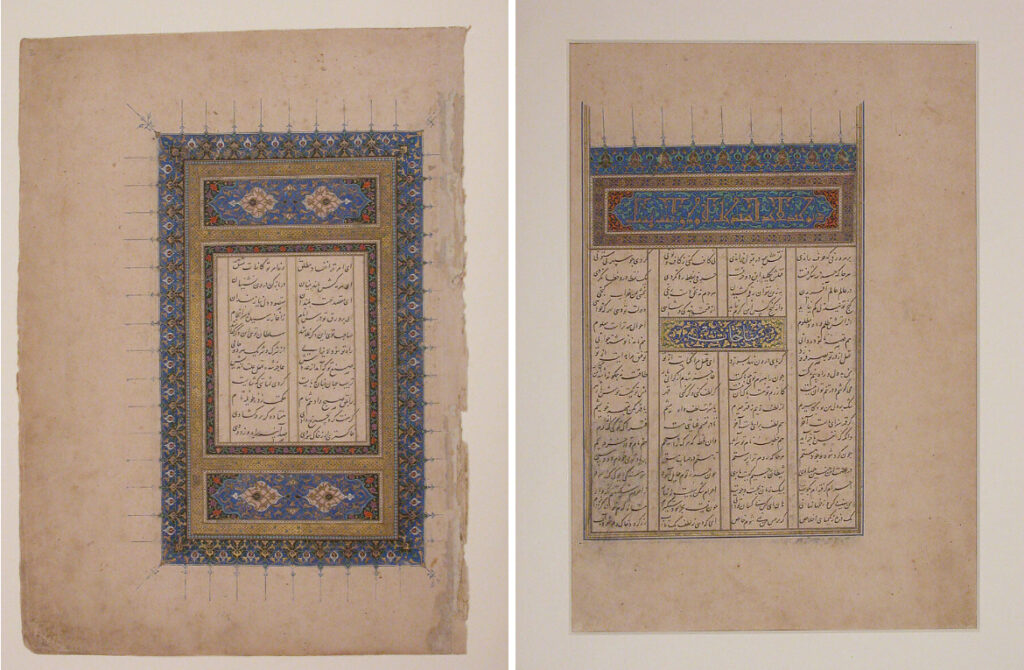

Laila and Majnun

Title: Illuminated Opening Page Titled Laila and Majnun from a Khamsa (Quintet) of Nizami of Ganja

Creator: Ja’far Baisunghuri

Material: Ink, opaque watercolor, and gold on paper

Size: Page: H. 12 5/16 in. (31.3 cm) W. 9 in. (22.9cm)

Mat: H. 19 1/4 in. (48.9 cm) W. 14 1/4 in. (36.2 cm)

Date: 835 AH/1431–32 CE

Culture/Location: present-day Afghanistan, Herat

Source: The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Credit: Purchase, Lila Acheson Wallace Gift, 1994

The fine manuscripts of Persia had a custom of surrounding the first two pages of text with intricate decoration. The framing bands and panels with cartouches are characteristic of these Persian scrolls. The rich blue colors in the background of the designs were made from lapis lazuli sourced from Afghanistan, combined with gold as the dominating colors of the ornate design.

Lapis Lazuli in Color and Function

Title: Snuff bottle in the shape of a gourd

Creator: Unknown

Material: Painted enamel with lapis lazuli stopper

Size: H. 3 1/4 in. (8.3 cm)

Date: Qing dynasty (1644–1911), Qianlong period (1736–95)

Culture/Location: China

Source: The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Credit: Bequest of Edmund C. Converse, 1921

The color of the snuff bottle is painted to match its stopper, which is made from lapis lazuli. The paints used to color the enamel are likely imbued with lapis lazuli to achieve this matching hue. The symbolic design of the gourd represents progeny, with multiple gourds growing from one vine symbolizing many children in one family line.

Sumi-e Ink

Sumi-e, meaning black ink painting, is described as art done in monochrome, embodying Japanese aesthetics through the use of simple black ink and carefully curated negative space. Zen Buddhist monks from China introduced this style of ink to Japan in the 14th century. It was used as a spiritual practice, as the strong contrast of ink on white paper brought together the harmony of heaven and earth. Sumi-e is made of pine soot ink sticks mixed with animal glue, with small amounts of water added until the desired tone is achieved. Over time, the brush strokes were simplified and often combined with poetry to create the style we know today.

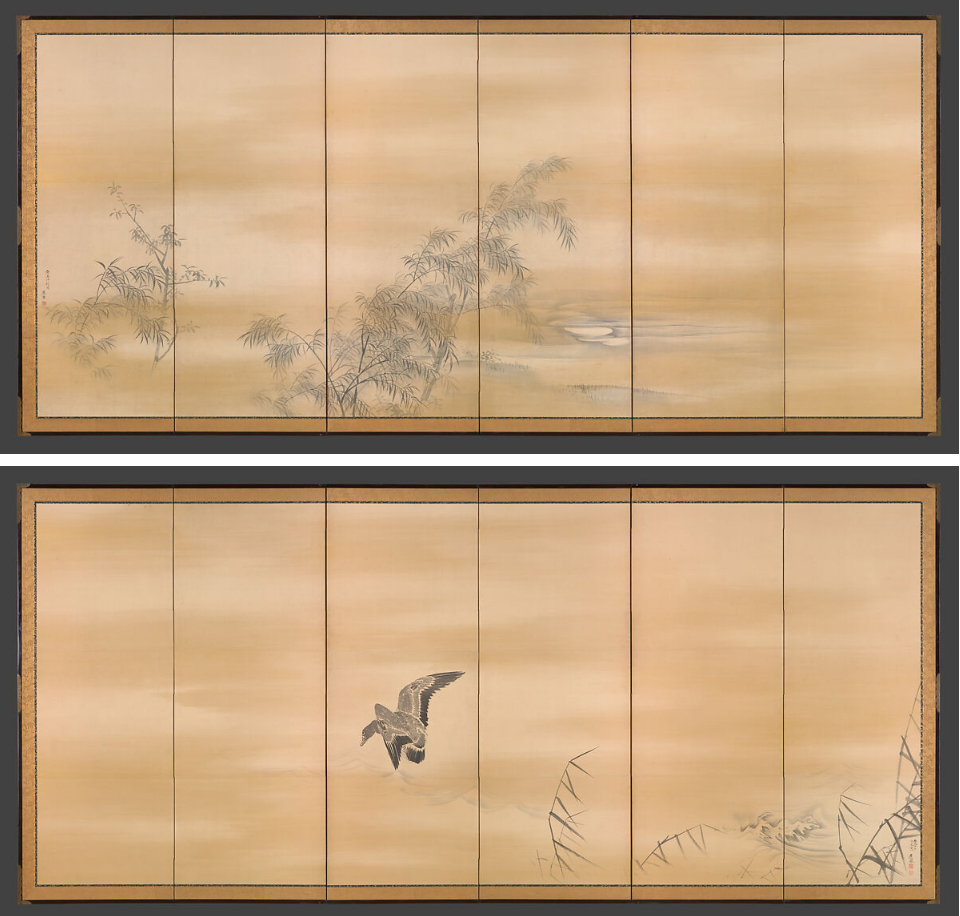

Goose and Reeds; Willows in the Moonlight

Title: Goose and Reeds; Willows in the Moonlight

Artist: Maruyama Ōkyo 円山応挙 (Japanese, 1733–1795)

Period: Edo period (1615–1868)

Date: right screen: 1774; left screen: 1793

Culture: Japan

Medium: Pair of six-panel folding screens; ink, color and gold on paper

Dimensions: Each: Image: 60 9/16 in. × 11 ft. 7 1/2 in. (153.9 × 354.4 cm)

Classification: Paintings

Credit Line: Mary Griggs Burke Collection, Gift of the Mary and Jackson Burke Foundation, 2015

Accession Number: 2015.300.197.1, .2

This painting depicts a goose with its wings half spread, swooping toward the surface of the water on the right-hand screen. The only indication of the shore is the tops of reeds bending beneath the wind. On the left screen, willow trees by the river stand in front of a lonesome reflection of the moon on the water. The viewpoint is low, and pictorial elements are closer to the viewer, giving depth to the background. Done in simple brush strokes with minimal crowding, it gives a sense of tranquility and almost an abstract or geometric perspective on nature.

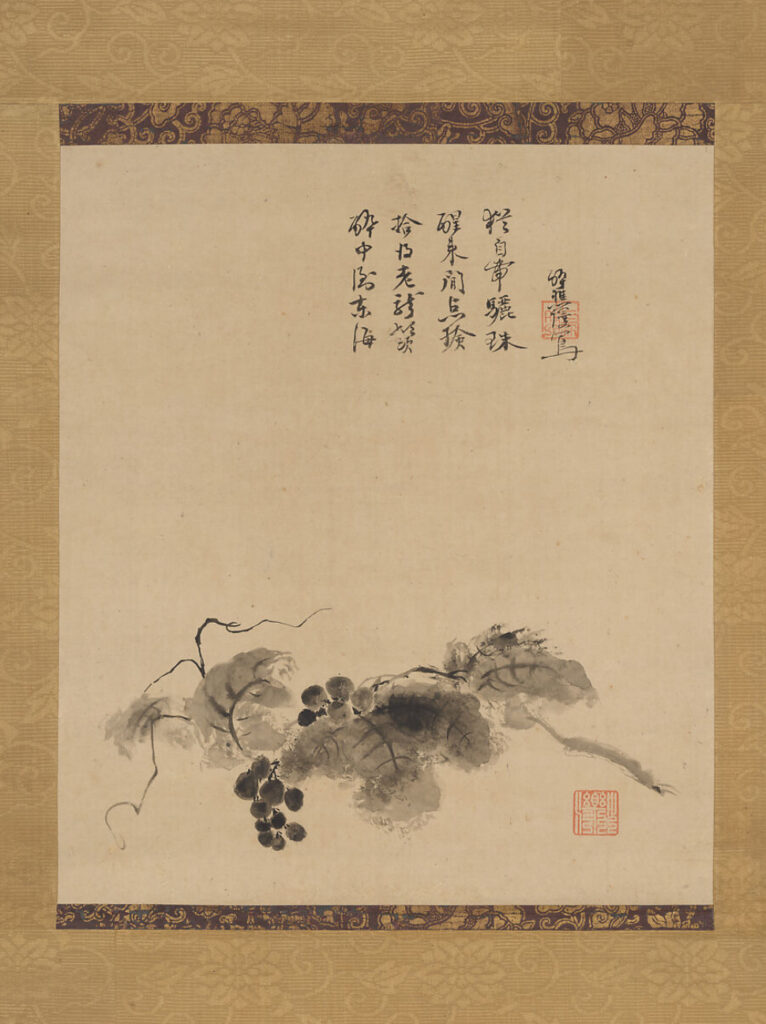

Grapes

Title: Grapes

Artist: Bokusai 墨齊 (Motsurin Jōtō没倫紹等) (Japanese, died 1492)

Period: Muromachi period (1392–1573)

Date: ca. 1480s–1492

Culture: Japan

Medium: Hanging scroll; ink on paper

Dimensions: Image: 17 9/16 × 15 3/16 in. (44.6 × 38.6 cm)

Overall with mounting: 50 7/8 × 20 9/16 in. (129.2 × 52.2 cm)

Classification: Paintings

Credit Line: Mary and Cheney Cowles Collection, Gift of Mary and Cheney Cowles, 2022

Accession Number: 2022.432.7

This painting is a still life cluster of grapes in various tones of ink by a Zen monk-painter. Compositionally, only the bottom third of the nearly blank surface is painted. For the finishing touches, the artist uses his own fingers to create the round grapes. A Chinese poem in calligraphy is included, meant to be read metaphorically, describing a spiritual journey the artist entered under his Zen Master. This painting reflects the origin of Sumi-e painting, known as the “Japanese style,” which was introduced by Zen Buddhist Monks. It begs the question “How can multiple cultural identities in Asian art be problematic? In what ways can it cultivate a larger community?”

醉中倒東海

拾得老龍鬚

醒來間点撿

獨自帶驪珠

While drunk,

I fell into the Eastern Sea,

reaching for and grasping

the aged dragon’s whiskers.

After finally awakening,

and examining things,

I am all by myself, carrying

The dragon’s black pearls.

(Translated by Tim Zhang)

Henna/Mehndi

Henna or Mehndi (Urdu) has been used for centuries in many cultures within South Asia, North Africa, and the Middle East, with roots traced back over 5,000 years. The leaves of the henna plant contain lawsone, a red-orange dye molecule that binds to the keratin in skin, hair, and nails. The process involves creating a paste from dried leaves, which is often mixed with essential oils and applied to the skin, leaving stains ranging from orange to deep red-brown.

How was Henna discovered ?

Originally used for its cooling properties in hot desert climates, henna has been embraced by various cultures worldwide. Each culture that uses the dye reflects its unique aesthetic symbolism and traditions. Similar to Sumi-e art, henna is both a dye and its own artistic style, seen across different cultures in Asia and beyond, fostering community connections. While “traditional” designs, mainly featuring florals and swirls, remain timeless, modern styles with a more tattoo-like appearance continue to emerge. Henna has a multitude of diverse uses beyond its decorative applications.

Comparison: Historic vs Modern Pigment

The aforementioned pigments served as stepping stones for the paints we all know and love today and the techniques discovered all those years ago still carry merit in the creation of pigments today.

Purple: Past purple pigments were synthesized from synthetic barium copper silicate and the modern equivalent still uses the mineral form as well as some hybrids of the color

Yellow: The practice of creating Indian yellow was stopped after the realization that the diet of the cows who were producing the pigment was unethical, and now the pigment is created from modern hybrids as well as mineral compounds

Green: Due to the instability of malachite green, modern day, consumers of the colors are usually using a hybrid of the mineral compounds that has achieved greater thermal calcination to perform better

Red-Orange/Brown: Henna is still used in present day art, as its composition as an effective dye and pigment is simple and timeless

Black: Sumi-E ink is also still a commonly used pigment, upholding its cultural permanence as well as newfound global recognition

Resources

- Liu, Z., et al. “Influence of Taoism on the Invention of the Purple Pigment Used on the Qin Terracotta Warriors.” Journal of Archaeological Science, vol. 34, no. 11, 2007, pp. 1878–83, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jas.2007.01.005.

- de Faria, Dalva L. A., et al. “A Definitive Analytical Spectroscopic Study of Indian Yellow, an Ancient Pigment Used for Dating Purposes.” Forensic Science International, vol. 271, 2017, pp. 1–7, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.forsciint.2016.11.037.

- Pantoja Muñoz, Leonardo. “Non-Invasive, Non-Destructive and Portable Identification of Indian Yellow: Moving from Highly Purified Standards to Real Watercolour, Oil and Historical Samples.” Journal of Cultural Heritage, vol. 62, 2023, pp. 441–48, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.culher.2023.06.022.

- “Colour in Art: A Brief History of Blue Pigment.” Art UK. Accessed March 6, 2024. https://artuk.org/discover/stories/colour-in-art-a-brief-history-of-blue-pigment.

- Rutherford J. Gettens,Elisabeth West Fitzhugh “Malachite and Green Verditer” Studies in Conservation, Vol. 19, No. 1 (Feb., 1974), pp. 2-23 (22 pages), https://www.jstor.org/stable/1505631

- Anilkumar, Smitha. “Henna.” Heart Views, vol. 22, no. 1, 2021, pp. 79–79, https://doi.org/10.4103/HEARTVIEWS.HEARTVIEWS_29_21.

- “Exploring Differences between Mineral & Modern Pigments.” Nancy Reyner. Accessed May 2, 2024. https://nancyreyner.com/2021/12/06/understanding-mineral-and-modern-pigments-for-painting/%0A .