Introduction

The spaces we inhabit hold profound significance, shaping not only physical surroundings but also our inner worlds. In an attempt to understand and harmonize these spaces, ancient people of China looked to the philosophy of Feng Shui, as it offers profound insight into the interplay between environment and the human condition.

Origins and call for Feng Shui

In the age of early vernacular dwellings, Chinese communities were clustered in nucleated systems, or scattered among fields and mountains (Figure 1). In these agricultural landscapes, the labor of the land sustained life itself and the fate of these communities was bound to the cycles of the natural world. The weather, sunlight, fertility of land, floods, and accessibility of water all directly dictated the lives of these people.

(Figure 1)

Peach Blossom Spring,

hand Scroll, ink and paper,

Image: 9 1/2 × 74 5/8 in. (24.1 × 189.5 cm),

Zhang Hong, Chinese, 1638

The call for Feng Shui arose as an organization to harmonize with the forces of nature. It acts as a symbiotic relationship between humanity and nature, where the layout and orientation of homes mirror the cosmic rhythms believed to govern the universe. The belief is that aligning with these cosmic patterns would offer protection and prosperity amidst the uncertainties of existence. For these communities, Feng Shui was more than a superstition; it was a pragmatic response to the challenges of their environment. By following these cosmic patterns, they believed they could ward off misfortune and cultivate prosperity, ensuring the well-being of their families. For in the harmonious alignment of space and spirit lies the key to unlocking the full potential of the human condition.

To define Feng Shui within an epistemological framework would be a pointless endeavor. Unlike Western disciplines that fit into categories of art or science, Feng Shui exists as an enigmatic entity, it is an unnameable discipline that defies classification. It exists as a melange of arts and sciences, weaving together principles of architecture, planning, geomancy, and philosophy into a cohesive whole. At its core, Feng Shui embodies an ancient cosmology–a worldview that recognizes the interconnectedness of all things and seeks to harmonize human endeavors with the cosmic order.

The significance of Feng Shui lies in attaining harmony within the symbolic realm of the cosmos, buildings, and settlements, enabling the Chinese to identify themselves within the vast expanse of time and space. Ultimately the aim is an auspicious existence, which for a believer in the cosmological system is obtained by working in harmony with it. In doing so, the satisfaction would be felt as an aesthetic pleasure because it would confirm one’s activities to be in harmony with the universe. By harnessing good influences and avoiding harm, humans seek to align themselves with the dynamic cosmic order embodied in the earth, positioning themselves to receive the positive influences of the universe. It is through the strategic placement of objects, structures, and landscapes that practitioners seek to optimize the flow of Qi, ensuring harmony and balance within the environment.

Understanding Feng Shui Elements

Central to Feng Shui is the belief in the cosmic force known as Qi. This force, both beneficial and malignant, shapes the landscape and influences human existence. The ancient text “Tsang-Shu,” dating back to the Chin Dynasty (265-420), defines the essence of Qi, stating that “it can be scattered when it meets wind and it could be stopped when it meets water” (Hwangbo pg. 112, 2002). Qi permeates the universe, infusing every aspect of existence with its unseen presence. Much like fish in water, humans are immersed in the ethers of Qi, carried along by its currents whether they perceive them or not.

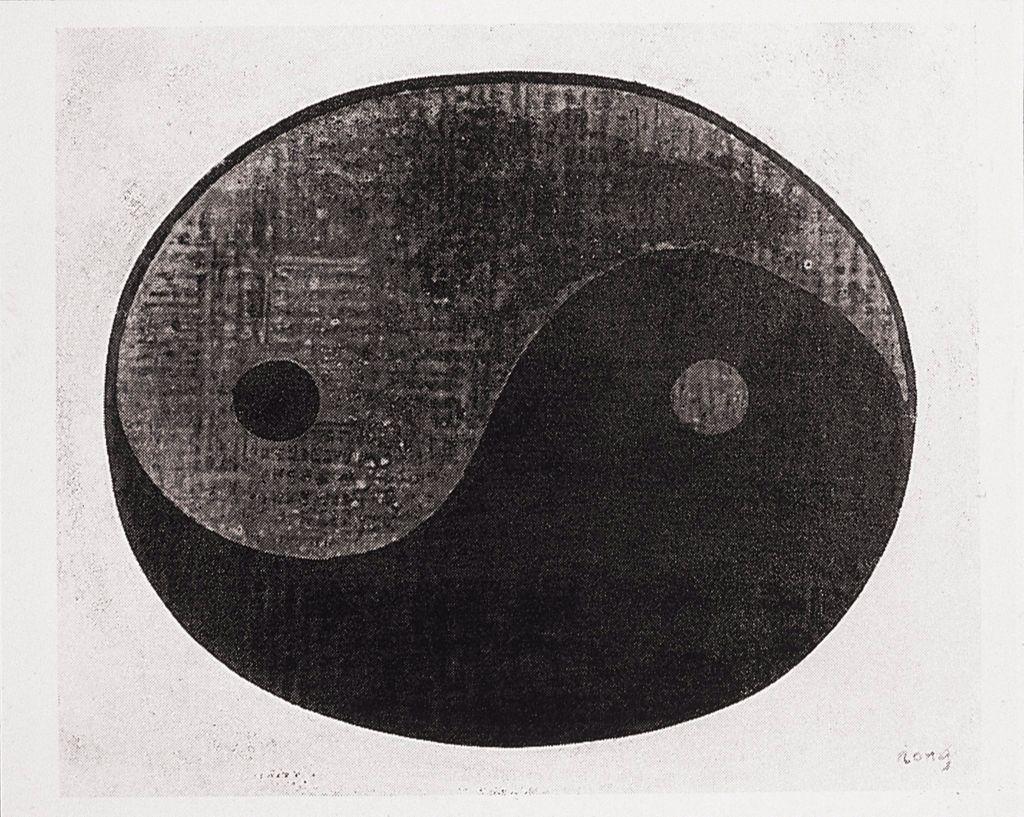

The concept of Yin and Yang emerges as a foundational principle, illuminating the dynamic interplay of opposing forces within the universe. Ancient Chinese philosophers regarded the universe not as a static entity, but as a living organism sustained by the flow of qi, the essence of life force. Within this framework, Yin and Yang are understood as complementary yet opposing states of Qi, embodying the dualistic nature of existence. Yin, symbolized by shade, represents darkness and receptivity, while Yang, symbolized by light, embodies brightness and activity (figure 2). This abstract duality of balance transcends to the natural world, where Yin and Yang manifest in succession – seen in the rise and setting of the sun, the blooming and withering of flowers, and the ebb and flow of tides. However neither Yin nor Yang exists in isolation, each contains within itself the seed of the opposite. A dot of the opposing color resides within each current (teardrop), symbolizing the incompleteness of Yin and Yang without the presence of the other. It is through the integration of these opposing forces that the concept of Tao, representing oneness and ultimate truth is realized, a state of existence characterized by perfect balance and harmony.

(Figure 2)

Composition,

1969-70,

oil and gold leaf on canvas,

18 x 21 1/2 in,

University of California, San Diego

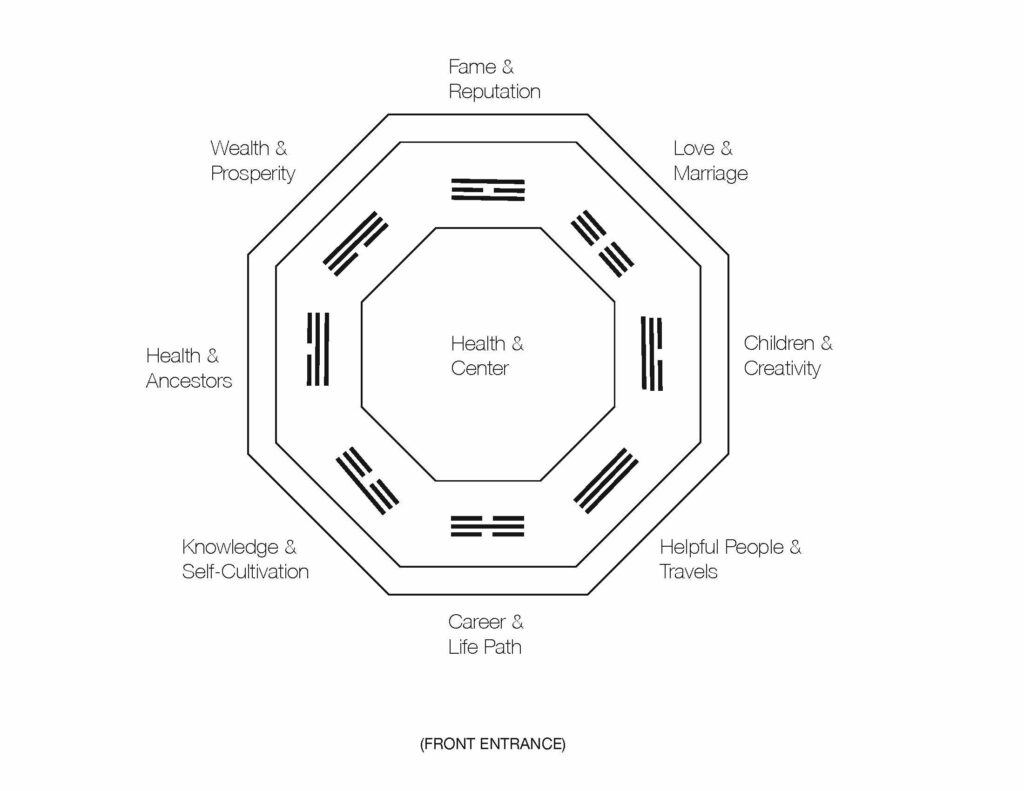

In the practice of Feng shui, the Bagua, or eight trigrams, is used to guide the flow of Qi within a space. Each facet of the bagua corresponds to a distinct aspect of daily life, ranging from career and family to health and creativity (Figure 3). When overlaid onto a floor plan, the bagua serves as a roadmap, revealing how Qi circulates through segmented surroundings and influences one’s experiences. Similar to how a dam upstream can obstruct the flow of water downstream, an excessive focus on one area of the bagua, while neglecting others may lead to disruptions in the flow of Qi. By aligning the bagua with our physical spaces, one can ensure a balance between Yin and Yang energies.

(Figure 3)

Actionable Principles

Humans are active participants capable of both preserving and manipulating the natural landscape. “[Feng Shui] not only interprets the environment on the basis of certain assumptions but also has practical implications for the environment itself” (Tsu, pg. 66, 1997) Feng Shui practices operate within a dynamic interplay, where humans exert influence on the environment and vice versa. It is through this two-way relationship that the principles of Feng Shui come to bear on the natural world. Efforts to preserve or modify essential features of the landscape are undertaken with the aim of enhancing the geomantic worth of a site, ensuring its vitality and longevity. Conversely, when the environmental integrity of a Feng Shui site is compromised, it falls upon the affected community to address/rectify the damage, thereby maintaining the balance between human intervention and natural harmony.

Central to Feng Shui principles is the orientation of buildings in relation to natural elements, with a belief that the surrounding environment serves as a vital source of Qi. it is customary for Feng Shui structures to align themselves with a water body in the front and mountains in the back, harnessing the dynamic energies of water and earth. Sunlight and natural ventilation further promote the flow of Qi within a space. Ample natural light not only illuminates interiors but also brings with it positive energy, creating a sense of vitality and warmth.

The arrangement of doors and windows also plays a crucial role in regulating the flow of Qi within a building. Direct alignment of doors and windows in a row is avoided as it may result in stagnation and discord. Similarly, doors that touch when fully opened are avoided, acting as barriers to the free movement of energy and potentially fostering disagreements within the household.

Curved walls and architectural elements are essential in facilitating the flow of Qi within a space. By incorporating gentle curves and organic shapes, architects create pathways for energy to circulate freely, promoting a sense of fluidity and balance. However, it is essential to strike a delicate equilibrium, as an excess of curves may lead to excessively high levels of Qi, resulting in discomfort.

Case Studies

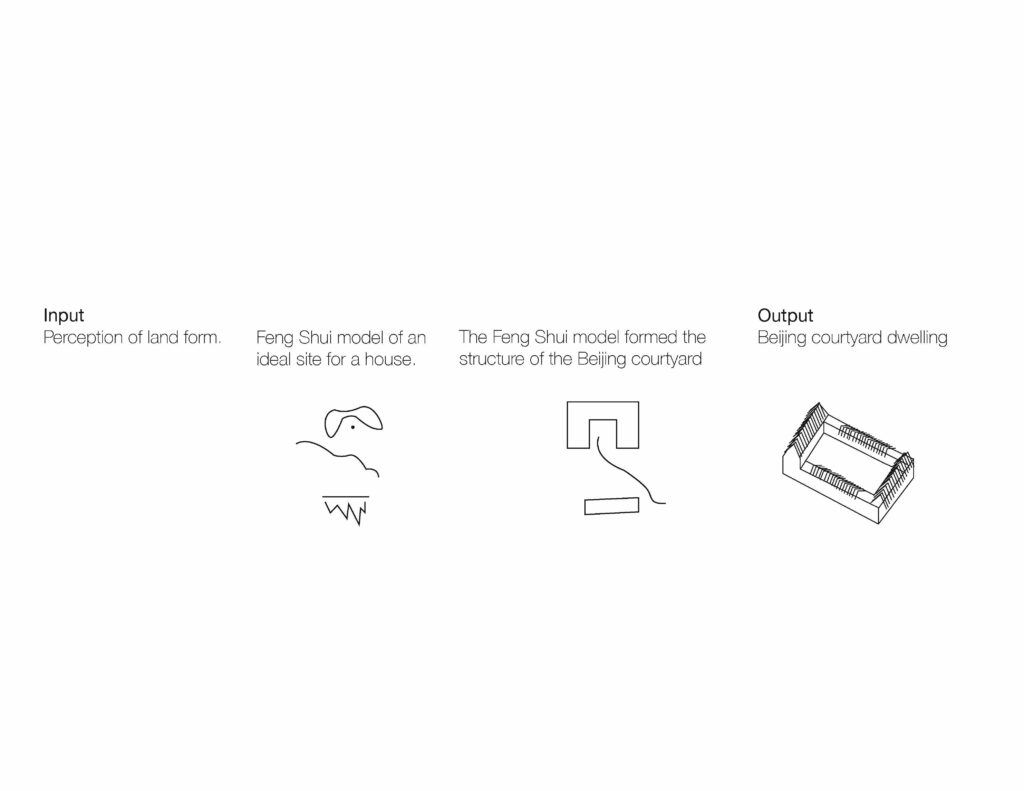

The Beijing courtyard house exemplifies the integration of Feng Shui principles into traditional Chinese residential architecture (Figure 5). Central to their design is the consideration of environmental factors, both physical and spiritual, which shape not only the physical space but also the social fabric of these dwellings. The application of Feng Shui principles to site selection involves two major aspects: dealing with landforms and arranging Qi. Dealing with landforms addresses the relationship of Qi with the surrounding mountains, hills, and water while arranging Qi emphasizes its relationship with orientations and positions. These principles influence the design of Beijing courtyard dwellings, shaping their layout and organization.

The ideal Feng Shui model of landforms dictates that a favorable site for a dwelling is embraced by surrounding hills, referred to as “tiger and dragon hills,” evoking the protective embrace of a mother. Facing southward, with a view of a prominent mountain peak, symbolizing ancestry and stability, the site is strategically positioned. An open space, typically featuring a lake or meandering river, lies in front of the site, serving as a conduit for vital Qi energy (Figure 6).

(Figure 5)

The organization of the courtyard house reflects the balance of Yin and Yang energies, with the courtyard representing Yang enfolded by surrounding buildings symbolizing Yin. The courtyard itself is enclosed by major rooms facing south. The two wings together form a “u” shape, mimicking a hill, the opposite screen wall with its hanging flower symbolizes a mountain, and the yard, the valley of an ideal Feng Shui landscape. The balance symbolizes family harmony and happiness and creates a harmonious microcosm within the built environment.

Visitors to the courtyard house are guided through an indirect spatial sequence, symbolizing a meandering river that accumulates Qi. It is believed that favorable Qi passes through a meandering path, while evil Qi prefers a straight line, embodying the harmonious equilibrium sought after in these dwellings.

(Figure 6)

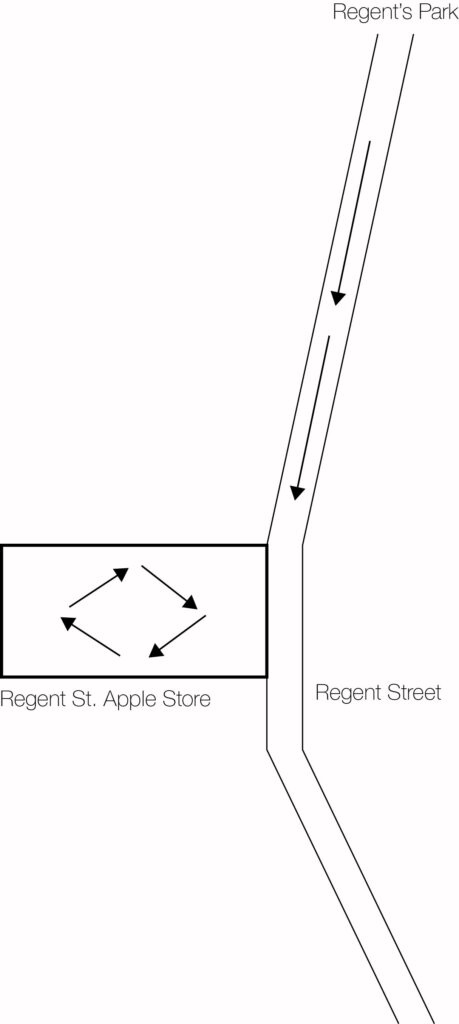

“Regent Street Apple Store, London”

Digital Photograph,

2007,

Marc Cluet

In stark contrast to the traditional Beijing courtyard houses, the Apple Store at Regent Street in London embodies a modern interpretation of Feng Shui principles within a commercial setting (Figure 7). Designed by Foster + Partners, the storefront harnesses the flow of energy in innovative ways to create a space that captivates and engages visitors.

Situated close to Regent’s Park and strategically oriented to receive energy from its surroundings, the store sits on a slight bend, enhancing its connection to the natural landscape (Figure 7). The energy that originates from the park flows down Portland Place and Regent Street and goes directly into the store. Once in the store, the energy is forced to move in a circular manner. Due to the open-plan layout and low benches, there is no object to redirect the flow of this energy. As the Qi enters the space, it flows in a clockwise direction through the store. It is believed that when Qi mirrors the flow of water in an area, it leads to a comfortable environment. In the northern hemisphere, water moves anticlockwise, so the Qi inside the Apple store should move anticlockwise. However, it is made to flow in the opposite direction instead, leading to confusion as opposed to comfort. This was done to encourage users to make impulse purchases and get reeled in by sales pitches more easily. If a buyer can’t think logically, they are likely to spend more money. Apple’s Regent street location makes more money than most of the company’s other stores in London.

(Figure 7)

Works Cited

Hwangbo, Alfred B. “AN ALTERNATIVE TRADITION IN ARCHITECTURE: CONCEPTIONS IN FENG SHUI AND ITS CONTINUOUS TRADITION.” Journal of Architectural and Planning Research No. 2, no. No. 2 (2002). https://www.jstor.org/stable/43030604searchText=&searchUri=%2Faction%2FdoBasicSearch%3FQuery%3Dfengshui&ab_segments=0%2Fbasic_search_gsv2%2Fcontrol&searchKey=&refreqid=fastly-default%3A8d36477ca5d07f112eefae47c1e5d6c4&seq=7.

Li Chang, William, and Peirchyi Lii. “”FENG SHUI” AND ITS ROLE IN CORPORATE IMAGE AND REPUTATION: A REVIEW FROM BUSINESS AND CULTURAL PERSPECTIVES.” Journal of Architectural and Planning Research 27, no. 1 (2010). https://www.jstor.org/stable/43030888?searchText=&searchUri=%2Faction%2FdoBasicSearch%3FQuery%3Dfengshui&ab_segments=0%2Fbasic_search_gsv2%2Fcontrol&searchKey=&refreqid=fastly-default%3A8d36477ca5d07f112eefae47c1e5d6c4&seq=2.

Tsu, Timothy. “Geomancy and the Environment in Premodern Taiwan.” JSTOR, 1997, www.jstor.org/stable/1178788?searchText=fengshui&searchUri=%2Faction%2FdoBasicSearch%3FQuery%3Dfengshui%26so%3Drel&ab_segments=0%2Fbasic_search_gsv2%2Fcontrol&refreqid=fastlydefault%3A938360d0ec72553da1d945728645c1c8&seq=1.

Xu, Ping. “‘FENG-SHUI’ MODELS STRUCTURED TRADITIONAL BEIJING COURTYARD HOUSES.” JSTOR, 1998, www.jstor.org/stable/43030469?searchText=feng+shui+in+Chinese+architecture&searchUri=%2Faction%2FdoBasicSearch%3FQuery%3Dfeng%2Bshui%2Bin%2BChinese%2Barchitecture%26so%3Drel&ab_segments=0%2Fbasic_search_gsv2%2Fcontrol&refreqid=fastly-default%3Af470fa09fad796244d9521f81d7ddb79&seq=1.

“Dr Michael Oon – the Feng Shui Consultant.” 2022. Michaeloon.com. May 28, 2022. https://michaeloon.com.