Introduction

The Olympics is a world-renowned sporting event that has been taking place over 3,000 years. Every two years, the world of athletics and competition comes together to celebrate the unity of diverse backgrounds and cultures. The Olympics also create a stage for its host city, allowing them to showcase their advancements and achievements, ranging from infrastructure, technology, culture, economic standings, sustainability, and overall success.

As a striving up-and-coming city, Beijing chose to bid to become a host city for the 2008 games. For a host city, winning the bid to hold the games is not just a matter of high prestige, but also a chance to create a positive impact on the urban landscape. This process began in 1993, when the People’s Republic of China, led by (then) President Jiang Zemin believed that the Olympics would be the perfect opportunity to showcase the city. The proposal consisted of many things, such as its vision for the games, creating a slogan; “One World, One Dream”

During the years following their winning announcement, Beijing began to make improvements around the city to prepare for holding such a large-scale event. From 2002 to 2006, almost 40 billion dollars were invested into the infrastructure of Beijing. By studying the games that came before 2008, China was successfully able to create an action plan that included sports facilities, transportation improvement,, and overall urban revampage, while satisfying the International Olympic Committee’s demands.

Not only was Beijing hoping to become more of a world figure, but it also wanted to present its rich culture and traditions. Therefore, there are many examples of Chinese traditional cultural aspects intertwined into the inspiration, design, construction, and use of these Olympic structures.

This publication aims to examine how Beijing’s modern 2008 Olympic Games structures incorporate elements inspired by ancient Chinese ideals. The integration of traditional Chinese values into these contemporary architectural designs reveals the intricate connections between China’s past and present urbanity. These buildings not only hold these traditional aspects but also reflect on the social and cultural climate during the time of construction.

Additionally, the chosen architects to design these projects are important to further understand, as they participate in shaping Beijing’s goals of becoming a renowned city. This can be seen through studying these architects’ innovative approaches to sustainability and technological innovation. There are so many multifaceted layers to the creation of Beijing’s Olympic architecture, and this publication aims to shed light onto how these buildings supported traditional Chinese motifs, to transform Beijing into a more sustainable and advanced metropolis.

The buildings chosen to research range from iconic Olympic structures, to important transportation hubs and key buildings that emerged from Beijing around the same time as the games. Each of these buildings shows quality and care in design choices and reflects the city’s agenda for advancement. By examining the choices and design principles of these buildings, this broad narrative of Beijing’s transformation is revealed.

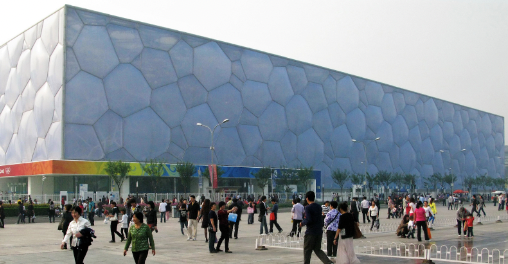

Project 1: Water Cube

The first of many iconic structures created for these games is the Water Cube. This project was created to host all of the aquatic events for the games. In 2003, the Australian-based architecture company PTW won the contract to design and create it. They also worked alongside Arup, a UK-based engineering firm (with a strong base in Australia), as well as the China State Construction Engineering Corporation (CSCEC). There were many reasons that these companies were design winners for this project. Ultimately, PTW had a long-standing reputation, as well as a greater amount of international presence with its other projects. They had also been chosen as the designers for the Sydney Olympic Park Aquatic Centre, used during the 2000 Sydney Olympics.

When designing the Water Cube, traditional themes of Chinese culture were greatly considered in various ways.

The connection of the Water Cube to water itself holds significant importance (especially with it being the main location for the aquatic competitions of the games). Water is highly valued in Chinese culture and comes about in traditional artworks and texts, as well as in Daoist, Buddhist, and Confucian ideas.

The Hawaii Journal of the Humanities offers detailed insight into some of these examples.

They discuss how water is linked to feelings of peace, freshness, and clarity of mind within Daoism and Chinese Buddhism. They also emphasize the simplicity of water, its soothing movement and sound, and its sense of expansiveness and relaxation.

It’s also important to note the Water Cube’s relation to the rest of the Olympic site, especially the Bird’s Nest stadium. Both structures are located about 800 feet from one another, making these two buildings not only physically close but also symbolically linked, creating an idea of unity. An important connection that Ben Sampson noted in his article about the legacy of these two structures is their connection between Yin and Yang. In traditional Chinese ideals, Yin and Yang represent complementary forces. This is because “In China red is male, blue is female, round is about the heavens, square is about the earth.” This directly matches up with the rigid, blue-lit exterior of the Water Cube, and the red, intertwined, round-shaped Bird’s Nest.

PTW’s innovative design visions for the Water Cube were also what pushed them to win the design bidding. A written interview with Tristram Carfrae of Arup goes into extensive detail on the mindset and design choices leading up its construction.

They started by discussing the properties of creating such a large indoor swimming pool, deciding that the best way to go about this would be to create “an insulated greenhouse with diffused natural light, and the main steel structure housed in a cavity, isolated from both the outside and the corrosive pool atmosphere.” Using a material to clad the exterior, such as ETFE, was the most efficient means of construction. This led to the design team making more decisions on how the exterior should behave. Overall, the team decided to create this notion of a “continuous skin” that enveloped the whole frame of the building.

As the design process continued, the designers became invested in the idea of repeating soap bubble figures. Carfrae states that “4,000 ETFE bubbles make up the Water Cube cladding, with some as large as nine meters across. The roof is made from seven different bubbles; the walls from fifteen bubbles, which are repeated throughout.” This ETFE material seemed to be close to perfect to create the Water Cube. It is a durable plastic, cleans itself during rain, and can span large distances.

Continuing off of this greenhouse inspiration, the Water Cube is known to allow large amounts of natural daylight into the space, using the sun to passively heat the interior. This allows for the Water Cube to reduce energy consumption by around 30 percent. Carfrae also stated that he “..wanted a square footprint, because it offered the most effective way of including the facilities necessary to ensure the pool gets used after the Olympics.”

Project 2: Bird’s Nest

The second notable project from the 2008 Beijing Games is the Bird’s Nest. Located across from the Water Cube, this stadium was designed for track and field sporting events, as well as the opening and closing ceremonies. The stadium can seat 90,000 guests, and is 2.8 million square feet in size, taking a little more than five years to produce. In 2002, the Swiss architecture firm Herzog & de Meuron (founded by Jaques Herzog and Pierre de Meuron in 1978) won the bid for the project. The firm underwent several struggles in trying to achieve this project, such as “conservative criticism, budget reductions – nearly 50%! – and cultural symbolisms”

Another thing to note is Ai Weiwei’s decision to distance himself from the project. Although he worked alongside Herzog & de Meuron on the Bird’s Nest, his renouncement symbolizes his discontent with the Chinese government’s use of the building for political agendas. Josh Niland in Archinect News states that Weiwei had realized that the Bird’s Nest motives of promoting social freedom and progress, became entangled with broader socio-political narratives.

Similarly to the Water Cube, the engineering firm Arup also played a significant role in the design and production of the Bird’s Nest. Arup helped greatly with the structural engineering and development of innovative solutions, necessary in making the Bird’s Nest a successful stadium.

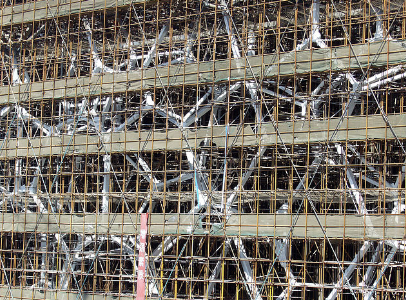

As the national stadium for the Olympics, The Bird’s Nest incorporates many traditional Chinese motifs, to present itself as a powerful symbol of cultural pride and power. The stadium’s design is rooted in the visuals of a bird’s nest, tying back to the importance of nature in traditional Chinese culture. Its metal lattice structure replicates the intricate weave of branches seen in natural bird’s nests, symbolizing unity and harmony. Other sources also reference the stadium as “an architectural forest,” as its beams and frames create imagery of that of a dense thicket. Again, the ideas of Yin and Yang come off strong from the Bird’s nest, as its circular shape opposes the geometric shape of the Water Cube. Although most believe that the Bird’s Nest is directly inspired by a nest figure, Arup states that much of the design inspiration comes from Chinese pottery. This helps to define the stadium’s seemingly random, yet advanced geometry pattern.

The design of the Bird’s Nest is unlike anything created in Beijing previously. A journal published by Arup, called The Beijing National Stadium Special Issue – The Arup Journal, the company goes into extensive detail on the stadium geometry, roof design, and overall dynamics needed to ensure its success. Arup states that their overall shape design had to respond to two main requirements; to have a moving roof (which ended up not being possible due to design constraints and costs), and to be able to withstand seismic events present in Beijing. As the design process continued, they found these exterior metal box-shaped curved elements to be tough to show. Many different design strategies were taken, such as the use of CAD, physical prototypes, and continuous reiterations. As mentioned before, thorough research was conducted to make sure that the roof could handle seismic forces.

Overall, the Bird’s Nest stadium is “purely structural: facade and structure are identical.” These exterior beams that intersect around the whole stadium seem to be organized in a random yet balanced manner, aiming to mimic the natural essence of a bird’s nest.

The Bird’s Nest emphasizes a dedication to sustainability as well, as seen through many of its design choices. Natural ventilation systems are used throughout the structure to keep spectators cool (especially during August– Beijing’s hottest month). Furthermore, the incorporation of ETFE material into the roof design allows more sunlight to enter, minimizing reliance on artificial lighting during the daytime. The stadium also includes rainwater harvesting technologies, and methods of solar power generation, to create usable energy.

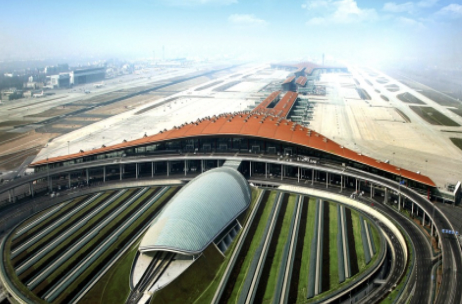

Project 3: Terminal 3 and South Railway Station

Two more projects that have significant meaning in the presentation of the city of Beijing are the creation of the new Terminal 3 at Beijing Capital International Airport, as well as the South Railway Station. Although these were not specifically put into action for the 2008 Games, they played an important role in the overall development of Beijing’s infrastructure, and ability to allow people to get to the games easily.

Construction for the terminal was brought up by the Chinese government in 2003, with construction starting in 2004. Its design was placed into the hands of several internationally renowned firms, like Foster + Partners, as well as Arup (once again). The construction phase of the project was extensive and was completed in March of 2008, right before the games, costing an estimated 625 million dollars.

As for the South Railway Station, construction began in 2004 as well and then completed soon before the commencement of the games. The detail on what firms designed the station is limited, although Arup also helped with the construction and engineering.

An airport is a very important place for design to reflect traditional Chinese motifs, as it is seen as the face of millions of visitors. These motifs can be seen in the overall shape of the roof, where sources state that its form represents the awe and thrill of a dragon. The yellow and red colors of the building also connect to those of traditional Chinese colors. Although there is no direct evidence of this, it seems as though the design takes inspiration from the principles of Feng Shui, as well as qi. These principles surround the idea that spaces are arranged to achieve a balanced harmony. The terminal reflects this and is arranged in a manner that allows travelers to best enter and move around the space, due to the orientation of the axis, and use of natural light.

The South Railway Station is similarly focused on its arrangement of space. Much of its design inspiration comes from the “Hall for Prayer for Good Harvests” in Beijing’s Temple of Heaven, according to Arup. Just as the temple is circular and tiered, the station is as well. The station’s qualities are also compared to traditional Chinese courtyard layouts, emphasizing a sense of openness and harmony with nature.

Project 4: National Indoor Stadium

Located North of the Water Cube, the National Indoor Stadium may not be as well-known, but played a vital role in the 2008 games. It served as the host for an array of sporting events, such as gymnastics, table tennis, and more. Designed by Glockner Architekten, a German firm, the stadium’s construction began in 2005 and was completed by late 2007.

While the National Indoor Stadium may reflect a more modern design, its inspiration draws from traditional Chinese ideals. When examining the building, it is believed to have taken inspiration from the shape and look of the traditional Chinese hand fan.

Hand fans formed different meanings in various Chinese cultures, according to the Atlantis Press’s research, exploring the culture and importance behind the hand fan. The article discusses the cultural differences between hand fans in the East and West. In the East, people of the upper class used the hand fan as a representation of status, and a ”tool of emotional sustenance.”

With this insight, the stadium hopes to evoke feelings of elegance and prestige. By resembling such an important cultural item, the National Indoor Stadium highlights the importance of cultural representation. In addition, its design connects to fluidity and movement, relating further to the properties of the hand fan.

Conclusion

In conclusion, there is a lot to uncover about Beijing’s modern buildings of the 2008 Olympic Games, and how they intertwine with traditional Chinese ideals. Each project serves its purpose in defining small traditional Chinese details. This was an especially important moment for Beijing, as it was able to showcase its use of innovative technology, materials, and design, while also tying in its rich historical culture. Hosting the 2008 Beijing Olympics not only allowed China to achieve this but also placed Beijing’s progress onto a global stage.

Bibliography

“Ai Weiwei Still Wants Nothing to Do with the Bird’s Nest Stadium Two Decades On.” Archinect. Accessed May 13, 2024. https://archinect.com/news/article/150297727/ai-weiwei-still-wants-nothing-to-do-with-the-bird-s-nest-stadium-two-decades-on.

Ancient Chinese philosophy and the wisdom of water. Accessed May 14, 2024. https://hilo.hawaii.edu/documents/humanities/journal/issues/Article2RonGordon.pdf.

Arquitectura Viva. “National Stadium, Beijing – Herzog & de Meuron .” Arquitectura Viva, January 14, 2021. https://arquitecturaviva.com/works/estadio-nacional-en-pekin-6#.

The Arup Journal. The Beijing National Stadium Special Issue, n.d.

“Beijing Airport – T3: Foster + Partners.” Archello. Accessed May 13, 2024. https://archello.com/project/beijing-airport-t3#:~:text=A%20symbol%20of%20place%2C%20its,yellow%20evokes%20traditional%20Chinese%20colours.

“Beijing Airport – T3: Foster + Partners.” Archello. Accessed May 7, 2024. https://archello.com/project/beijing-airport-t3.

“Beijing Capital International Airport Expansion, Chaoyang District.” Airport Technology, October 11, 2019. https://www.airport-technology.com/projects/beijingcapital/?cf-view.

Beijing National Stadium (birds nest) | download scientific diagram. Accessed May 7, 2024. https://www.researchgate.net/figure/Beijing-National-Stadium-Birds-Nest_fig5_335596459.

Carfrae, Tristram. “Engineering the water cube: a swimming pool made of bubbles. Tristram Carfrae of Arup outlines the engineering factors which led to the competition-winning Beijing Olympic Swimming Centre, by PTW, China State Construction and Engineering Co and Arup.” Architecture Australia, July-August 2006, 103+. Gale Academic OneFile (accessed May 13, 2024). https://link.gale.com/apps/doc/A150694572/AONE?u=connc_main&sid=bookmark-AONE&xid=179d63b3.

“The Bird’s Nest.” Never Enough Architecture, July 10, 2023. https://neverenougharchitecture.com/project/the-nest/.

“The Bird’s Nest.” Never Enough Architecture, July 10, 2023. https://neverenougharchitecture.com/project/the-nest/.

“Delivering Beijing South Railway Station – an Architectural Icon.” Arup. Accessed May 13, 2024. https://www.arup.com/projects/beijing-south-railway-station.

“Designing the National Aquatics Center (Water Cube) for Beijing Olympics 2008.” Arup. Accessed May 7, 2024. https://www.arup.com/projects/chinese-national-aquatics-center#:~:text=The%20building’s%20form%20is%20inspired,while%20appearing%20organic%20and%20random.

Digital, Carter. “Sydney International Aquatic Centre.” PTW. Accessed May 13, 2024. https://www.ptw.com.au/project/sydney-international-aquatic-centre.

Huang, Longshanshan. “Review of Development of Hand Fan in the East and West Cultural Backgrounds.” Atlantis Press, n.d.

“Jonathan Glancey Sneaks a Look inside Beijing’s New Olympic Stadium.” The Guardian, February 11, 2008. https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2008/feb/11/architecture.chinaarts2008.

“Jonathan Glancey Sneaks a Look inside Beijing’s New Olympic Stadium.” The Guardian, February 11, 2008. https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2008/feb/11/architecture.chinaarts2008.

“The Most Striking Structure of the 2008 Beijing Olympic Games.” Arup. Accessed May 13, 2024. https://www.arup.com/projects/chinese-national-stadium.

“One Flew over the Nest.” Center for Architecture, January 8, 2014. https://www.centerforarchitecture.org/news/one-flew-over-the-nest/.

Rose Etherington | 6 February 2008 22 comments. “Watercube by PTW Architects.” Dezeen, March 3, 2019. https://www.dezeen.com/2008/02/06/watercube-by-chris-bosse/.

Spa, Mondo. “The National Indoor Stadium in Beijing.” SpazioMondo | Mondo Spa. Accessed May 13, 2024. https://www.mondoworldwide.com/na/en/spaziomondo/olympics/project-the-national-indoor-stadium-in-beijing/.

Spa, Mondo. “The National Indoor Stadium in Beijing.” SpazioMondo | Mondo Spa. Accessed May 7, 2024. https://www.mondoworldwide.com/na/en/spaziomondo/olympics/project-the-national-indoor-stadium-in-beijing/.

“Water Cube – National Aquatics Center, China.” World Construction Network, June 2, 2023. https://www.worldconstructionnetwork.com/projects/watercube-aquatic-centre/?cf-view.

“Water Cube – National Aquatics Center, China.” Gallardo Architects, September 16, 2015. http://gallardoarchitects.com/water-cube-national-aquatics-center-china/.