Overview

I have put the order of examples in a chronological order of how feng shui was first traditionally used and how it has then moved on to applying in a bigger and important contexts. I start by introducing the traditional tools of feng shui because they are significant in understanding how feng shui was practically developed which is from the use of Song south-pointing needle or the spoon placed on square base and circular form. Then I move on with one of the earliest examples used in the ancient mausoleum, then to the palace, to the courtyard and modern era use of feng shui. Following this chronology helps to understand how it was first introduced to how it was traditionally used and then how the concept became a popular and vital philosophy in the modern world.

Throughout Chinese history and cultural development, there has been a significant impact on viewing the relationship between man-made built space and the natural environment. During the class discussions on topics of pagoda, palaces, symmetries, I was drawn to exploring why and how structural foundations had eight sides or positioned in a particular direction in a particular angle. I always knew that there was more to an eight-sided (octagon base) pagoda symbolizing the noble eightfold path or the five-story pagoda representing the five elements (earth, water, fire, wind and sky). Therefore, understanding the concept of feng shui has helped in connecting the ideas together.

Feng Shui, the ancient Chinese art of harmonizing individuals with their surrounding environment, has long been intertwined with the concept of designing and constructing buildings. With its root tying back to the principles of Taoism and traditional Chinese philosophy, feng shui emphasizes the delicate balance between the natural and built world, seeking to create structures that carefully align with the energy of nature or “Qi” of the given site. With its outcome of bringing in positive energy, well-being and ability to achieve other personal goals, feng shui has been in use in different contexts. Apart from the traditional examples, feng shui has also been used for organizing urban planning to identifying the placement of main entrance into the house to redecorating or cleaning up homes for greater happiness, balance personality and interior design that not only brought good qi to the users but also enhanced their work performance and achievements. This holistic approach to architecture has profoundly shaped the iconic structures of China from the Forbidden City in Beijing to the winding streets of ancient villages, and continues to influence modern design around the globe.

From ancient times to even in the modern world, architects have carefully studied the topography, wind patterns and the flow of Qi to determine the optimal placement and orientation of buildings. Feng shui practitioners carefully examine the natural features of a site, such as the slope of the land, the presence of water, and the direction of the wind to determine the most auspicious location for a building (Xu). Similarly, going into the details, the placement and orientation of a structure in relation to the cardinal directions, as well as the positioning of the doors, windows and other architectural elements are considered crucial in feng shui design in order to maximize harnessing the positive flow of energy (Charvátová).

Feng shui was developed in two schools; form feng shui and compass feng shui. The form feng shui relied mostly on the natural topography and focusing on identifying the natural flow of qi from the mountains and hills, as well as bodies of water (X). Natural elements like water and mountains carried strong qi, thus they were used as an essential guideline as to how life can be best supported in the environment. On the other hand, the compass feng shui relied mainly on the Luopan, a magnetic compass to determine the direction according to compass point. The compass feng shui is more occupied with cosmological order and cosmological correlations, including the numerical proportions to the compass directions, potentially bringing the entire range of Chinese cosmological speculation into play when investigating a site (Charvátová). While the form feng shui was based on subjective interpretation of the landscape, the compass feng shui was based on mechanical application of its principles and is often very difficult to practice due to its complicated details and requiring years of mastering the study.

The compass feng shui is one of the earliest ways to introduce the concept of feng shui. In ancient China, a compass, a magnetic device pointing north-south, was commonly used for divination. During the Han dynasty (206 BC-AD 220), practitioners used spoon-shaped compasses made of lodestone or magnetite ore for this purpose. These spoons were placed on square brass plates with circles at their centers, representing one of the earliest forms of Chinese south pointers. The square plate symbolized the earth, while the circular shape symbolized heaven, reflecting the practice of using these symbolisms to connect life on earth with the heavenly

FIGURE 1.1

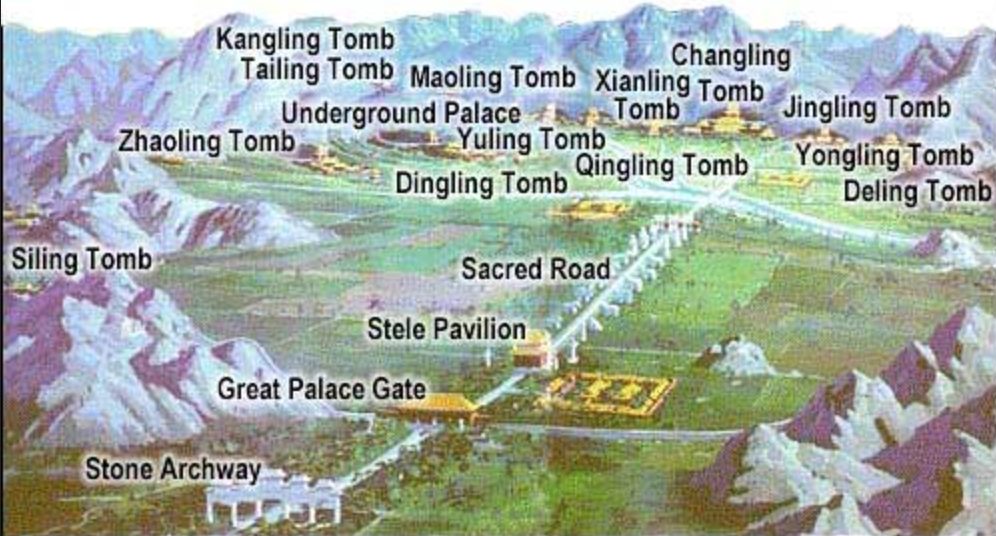

Title: The Ming Tomb

Date: 1368-1644

Culture: Ming Dynasty

Location: Beijing, China

Material: Timber and Brick

Photo Credit: Nathan Hughes Halimton

Hamilton, Nathan H. “Ming Tombs, 1987.” Flickr. Last modified January 31, 2016. https://www.flickr.com/photos/nat507/24375675899/in/photostream/.

Figure 1.2

Title: The Ming Tomb Sacred Way Stone Statues

Date: 1368-1644

Culture: Ming Dynasty

Location: Beijing, China

Material: Stone

Photo Credit: Nathan Hughes Halimton

Hamilton, Nathan H. “Ming Tombs, 1987.” Flickr. Last modified January 31, 2016. https://www.flickr.com/photos/nat507/24375675899/in/photostream/.

The Ming Tombs, located just north of Beijing, are a collection of mausoleums built by the emperors of the Ming Dynasty, known collectively as the Thirteen Tombs of the Ming Dynasty. Feng shui played a crucial role in determining their locations to maximize positive energy. The principles of feng shui were meticulously applied to harmonize the tombs with the natural landscape and harness the qi of the environment, creating an auspicious resting place for the Ming emperors. This careful organization and layout were believed to benefit not only the well-being of the deceased but also their descendants for generations to come

The Ming Tombs were situated in the Tianshon Mountains, which provided a natural protective barrier. The tombs were positioned at the foot of the mountains, with the peaks looming behind them. This ‘embrace’ of the mountains was considered an ideal Feng Shui arrangement, as it symbolized the protection and support of the natural world and perfectly harmonized with the natural elements. Similarly, the Baihe River that flowed in front of the tombs added more positive and spiritual energy into the site. The presence of water was seen as auspicious in feng shui, as it represented the flow of wealth and prosperity. The river’s sinuous path was also thought to guide the qi towards the tombs.

On the other hand, the tombs were carefully aligned to face the south, which was considered the most fortuitous direction according to feng shui principles. This particular orientation allowed the tombs to benefit from the warm, nurturing energy from the solar as well as the greatest protection from harsh north winds and sharp energies. The energy of the sunrise was considered as much more yang and stronger and life-enhancing than the sunset in the west which is yin or female energy.

In addition to the careful orientation of individual tombs based on feng shui principles, ancient architects and designers also emphasized the way people enter and experience the atmosphere and energies of the mausoleums. The entrance to the Ming Tomb complex features a grand ornate gate known as the “sacred way.” This gateway symbolizes a portal connecting earthly beings with the spiritual world of the Ming emperors. Lining the sacred way are rows of stone statues, including mythical animals and guardians, believed to possess protective powers that guide the spirits of the deceased emperors and ward off negative energies

Moreover, the paths are flanked by trees, enhancing a sense of peace and harmony. The intentional design of gentle curves in the paths and integration of natural elements aim to help the spirits of the Ming emperors transition smoothly from the earthly realm to the spiritual realm. Sharp edges and structures are avoided, as they conflict with feng shui principles and are believed to divert the flow of qi. Thus, the overall design of the Ming Tombs, from the entrance to the orientation of each tomb, is deeply rooted in feng shui principles, connecting earthly beings to the spiritual world through positive qi energy

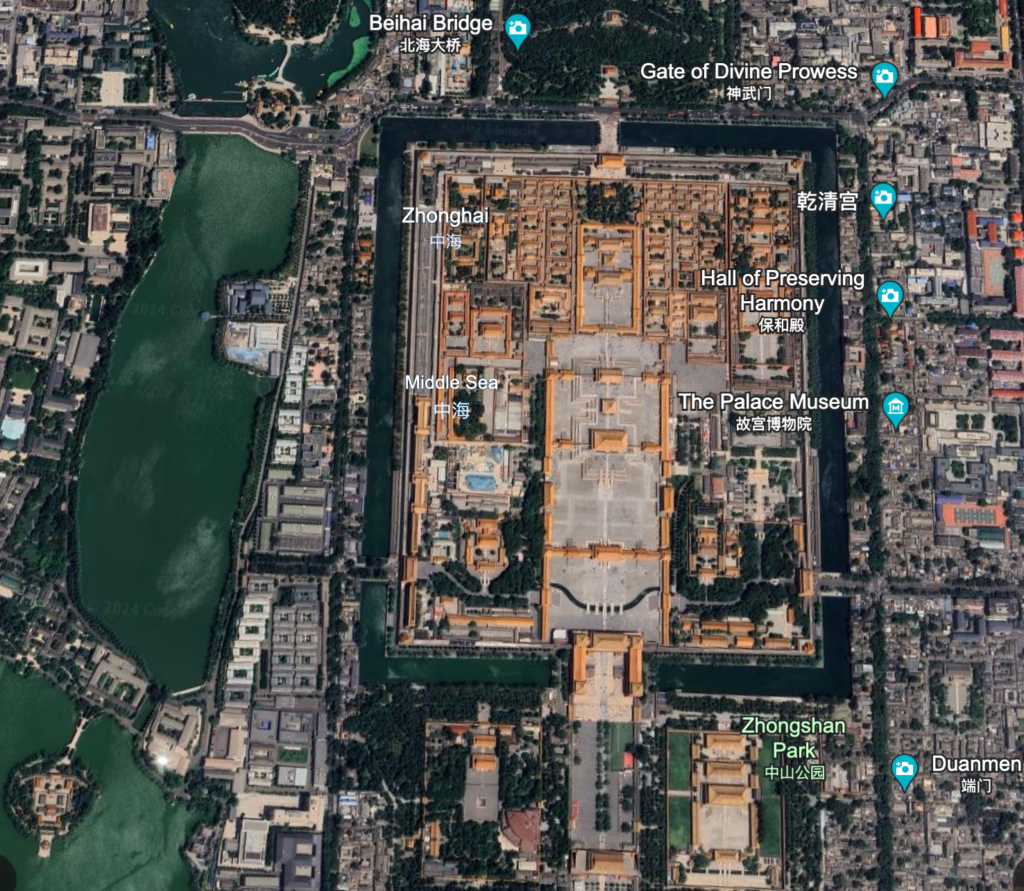

FIGURE 2

Title: The Forbidden City

Date: 1406-1420

Culture: Ming and Qing Dynasty

Location: Beijing, China

Material: Wood, Earth and Water

Photo Credit: Google Earth

The Forbidden City in Beijing, China, is a magnificent architectural wonder that showcases the seamless integration of traditional Chinese philosophy and design. At the heart of this harmonious blend lies the ancient practice of Feng Shui, which played a crucial role in the planning and construction of this iconic imperial palace complex (Baratta). The Forbidden City has used the form feng shui to observe the morphology of the mountains and rivers and of their relationship to winds in order to establish favorable places according to the presumed benign glow of qi. A ‘correct place’ in the form of feng shui must first of all have the tallest visible mountain to the north and a meandering river flowing to the south.

The Forbidden City was meticulously aligned along the north-south axis, ensuring that it was positioned in harmony with the cardinal directions. This alignment was a deliberate choice, as it was believed to harness the positive energies of the universe and bring balance to the imperial seat of power.

The layout of the Forbidden City is also meticulously symmetrical, with buildings and structures mirrored on either side of the central axis. This symmetry is a hallmark of feng shui, representing balance, harmony and the perfect union of yin and yang (Qi). This layout takes advantage of the natural landscape, with the Jingshan Hill to the north acting as a protective barrier and the Golden River to the south providing a natural moat. Mountains/hills and rivers were vital elements of boosting the principles of feng shui and getting the maximum positive energy out of it. Thus, these geographical features were carefully integrated into the overall design, enhancing the sense of security and reinforcing the power of the imperial court.

Apart from the overall layout of the city, feng shui principles are also used in organizing the details and decoration of the building in Forbidden City. For instance, the distinctive curved roofs of the Forbidden City’s buildings are not just aesthetically pleasing, but are intentionally designed to serve feng shui purposes such that they are believed to help deflect negative energy and channel positivity qi into the structures, promoting harmony and prosperity. Even the choice of materials such as timber, stone and ceramic tiles were carefully selected for their auspicious connection and ability to balance the five elements; wood, fire, earth, metal and water. These five elements and the colors associated with them are also used in sacred structures such as the Altar of Land and Grain and the Ancestral Temple that are used for making sacrifices to the Earth’s god. The temple sat in an open-air, three level square terrace of white marble and on the top, a basin containing soil of five colors:green (east), red (south), white (west), black (north) and finally yellow in the middle. The five-color soil symbolized the spiritual colors of feng shui but more than that the square base of the temple was associated with Earth and the round to Heavens, connecting the heavenly with the earthly through spiritual energy.

On the other hand, similar to the intentional designing of trees in Ming Tombs, the courtyard of the Forbidden City also incorporates natural elements such as ponds, gardens and trees, to create a harmonious blend of the built and natural environment. This integration of nature was a key aspect of feng shui, as it was believed to enhance the overall energy and wellbeing of the imperial residents.

FIGURE 3

Title:Beijing Courtyard Houses

Material: Wood and Earth

Culture: Ming and Qing Dynasties

Location: Beijing

Source: The Department of Architecture,Tsinghua University, Beijing

Xu, Ping. “‘FENG-SHUI’ MODELS STRUCTURED TRADITIONAL BEIJING COURTYARD HOUSES.” Journal of Architectural and Planning Research 15, no. 4 (1998): 271–82. http://www.jstor.org/stable/43030469.

The development of the courtyard reached its apogee during the Ming dynasty (1368-1644) and Qing dynasty (1644-1911). The courtyard house was the basic unit of the city; formal city planning arranged courtyard dwellings on a grid systemThe ancient Chinese brought the model of using natural elements to develop feng shui into their habitat when they needed to create a man-made space. Similar to the orientation of the Forbidden City and Ming Tombs, the courtyard houses were oriented along the north-south axis, with the main entrance facing south where the flow of qi was the strongest (Xu). According to the feng shui, a favorable site for a dwelling is enfolded by surrounding hills, called “tiger and dragon hills’ ‘ which symbolized the mother’s protection. Thus, with significant symbolism, the buildings correspond to mountains, roads to rivers and walls to hills.

The figure 3 courtyard shows the best example representing all the feng shui symbols discussed till now. The figure 3 Beijing courtyard is enclosed by buildings. The major rooms in the building face south, with the two wings together forming a U-shape, as a symbol of the tiger and dragon hills. The opposite screen wall with its hanging flower gate symbolizes the ‘facing mountain’. While the open space yard represents the natural landscape, the entrance is intentionally located at the southeast corner of the house, the direction from which, according to the feng shui masters, the vital qi comes. In the house, the courtyard (Yang) is enfolded by surrounding buildings (Yin); and the balance between them symbolizes family harmony and invites happiness and prosperity.

Conversely, the courtyard incorporates the concept of water/river in a unique way. The courtyards are designed and organized in such a way that when visitors enter through the main entrance, they would have to move around to the side and take turns as there would be a wall right when the visitor enters in order to block the view to the inside rooms. This indirect spatial sequence symbolizes a ‘meandering river’ which serves to accumulate qi rather than having an actual water flowing. Thus, the dictated circulation of the people becomes the flow of water, making the qi energy enter the space through redirections. Therefore, the Chinese developed their courtyard dwellings to represent miniature universes. Just like how the use of square and circle were associated with earth and heaven, the courtyard developers and users believed that the earth below (their courtyard) reflected the heaven above; mountains reflecting their stars, rivers reflecting milky way and leaving open courtyard to reflect heavenly sky. Thus, every design decision made towards creating courtyards were carefully planned and studied using the principles of feng shui.

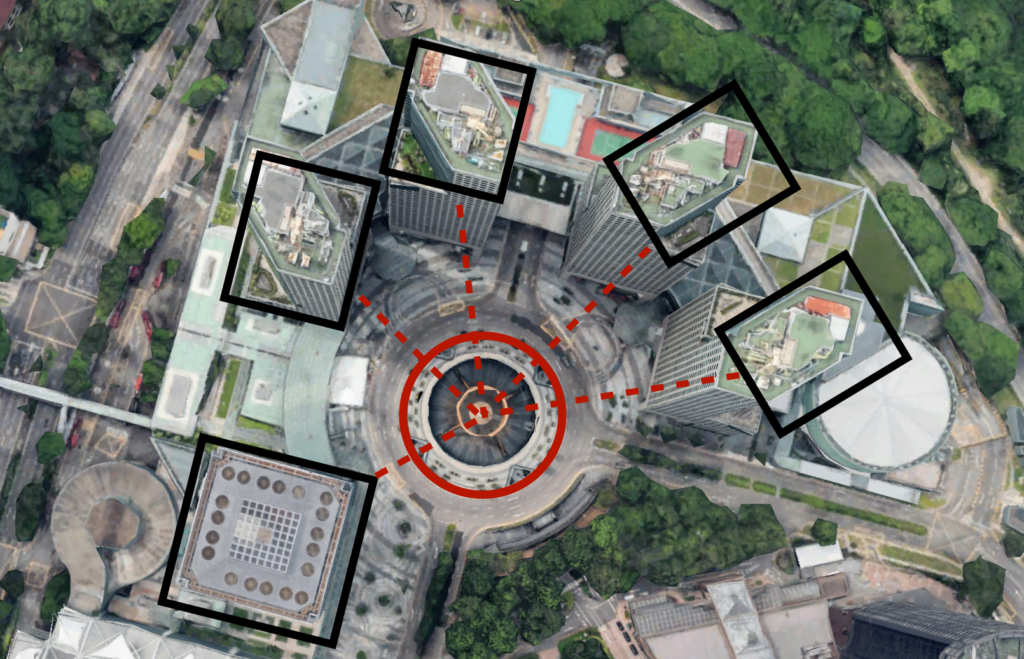

FIGURE 4

Title: Suntec City

Date of construction: 1995-1997

Location: Suntec City, Singapore

Dimension: 18-storey representing the thumb and four 45-storey offices towers the fingers

Architect: I.M.Pei and partners

Source: Google Earth; Edited by Kinley Yangden

The concept of feng shui was traditionally focused only on how to harmonize nature such as mountains, hills and water with the man-made landscapes and spiritual well-being. But in the modern days, more elements of feng shui are explored and ways to maximize these elements while still reaping the benefits are given more significance.

One of the most influential modern places that took the use of feng shui to a higher level is Singapore. Feng shui influenced the blueprint of some of Singapore’s major architectural structures, such as the layout and design of Suntec city. From an aerial view, the mall’s tower looks like an open palm with each tower representing five fingers. With the 18-storey representing the thumb, the four 45-storey office towers the fingers, and the convention center the wrist, while the Fountain of Wealth looks like a gold ring in the center of the palm. The circular design of the fountain is believed to be based on the Hindu mandala, which is a symbolic representation of the universal spirit. The fountain is also designed to capture the auspicious values of feng shui. According to the geomancers, the location of the fountain is the point of convergence of “five dragon heads” of Singapore. Water jets from the fountain’s bronze ring flow inwards, instead of outwards, into the center of the ring, symbolying the retention of wealth, bringing prosperity to both the building;s occupants and visitors. Since Suntec City Mall is one of Singapore’s largest shopping and entertainment centers, the use of feng shui principles not only helped in bringing positive qi energy but also elevated the ability to draw wealth into the commercial site.

The striking architectural design of Suntec City, with its bold and angular structure, reflects the Feng Shui element of fire. This element of passion, ambition and energy, inspiring a sense of dynamism and creativity within the complex. In the internal layout of the malls, all five buildings are interconnected and are designed to encourage the natural flow of energy. This layout is based on feng shui principles, which emphasize the importance of unobstructed movement and the avoidance of sharp corners or dead-end spaces. With the placement of fountains in the center of the five buildings, the qi energy would always have continuous flow around the circular path and go into the square buildings. The use of a circular water fountain and square five-finger representing buildings ties back to the traditional feng shui principles of circular symbolizing the heaven with squares symbolizing the earth. The connection of heavenly and earthly spirits and well-being are always put at the heart of design.

FIGURE 5.1

Title: The Gateway Building

Date of construction:1990

Location: Singapore

Dimension: 37-storey, 150m tall

Architect: I.M.Pei

Source: Google Earth; Edited by Kinley Yangden

FIGURE 5.2

Title: The Duo Tower

Date of construction: 2008

Location: Singapore

Dimension: 186 and 170 meters

Architect: Buro Ole Scheeren

Source: Google Earth; Edited by Kinley Yangden

Although the concept of feng shui is strongly rooted in the Singaporeran culture, modern and western architects and designers have often ignored the principles which have affected the surrounding environment. The Gateway Building, a renowned architectural landmark in Singapore, has long been the subject of discussion among the enthusiasts of traditional Chinese architecture and feng shui. Despite its striking design and prominence in the city’s skyline, this building has been criticized by some for its potential to disrupt the harmonious flow of energy, as dictated by the principles of feng shui. Thus, the building’s design may be considered to portray “bad” feng shui.

One of the main concerning features of the Gateway Building according to feng shui is its asymmetrical design. The building’s two towers are not perfectly aligned creating an imbalance in the overall structure and hence, disrupting the flow of qi. The unevenness of the buildings are also believed to create a sense of disharmony, as the uneven towers are seen to be ‘fighting’ against each other. Moreover, the sharp edges of the building resemble a lot to razor-sharp knives. In feng shui, such symbolism is often associated with negative energy, conflict, and the potential for ‘cutting’ or severing relationships and prosperity. Thus, the building does not harmonize in their structural placement and also with the surrounding environment, diverting from the principles of feng shui.

One way that the surrounding building and environment reacted towards this bad feng shui building is by creating ways to deflect the bad qi from its source. The Duo tower building was intentionally designed with concave exteriors to deflect the bad qi from the Gateway Building. Developers have also not constructed any other building in the neighboring area as the negative qi flow from the Gateway felt too strong that anything built in its radiance would not be in harmony with nature.

Conclusion

The ancient Chinese practice of feng shui has long been intertwined with the design and construction of buildings, from humble homes to grand imperial palaces. This profound philosophy, which seeks to harness the harmonious flow of energy, or qi, has left an indelible mark on architectural traditions across the world. In traditional Chinese architecture, the positioning and orientation of buildings were carefully considered in accordance with the principles of feng shui. Structures were often aligned with natural landscape features, such as mountains and rivers, to ensure the optimal flow of energy and to protect against negative forces. The use of specific colors, shapes, and materials were carefully practiced as they held deep and strong symbolic meaning rooted in the tenets of feng shui.

As the influence of Chinese culture has grown globally, the principles of feng shui have also become increasingly integrated into modern architectural design. Especially, in Singapore, architects and designers actively incorporate elements like the placement of windows, entrances, orientation of buildings and the use of specific materials to harness the positive qi and also other purposes that would also help in growing wealth.

Feng shui, if used correctly, has many positive impacts on the growth, harmony and connection with the heavenly spirits. However, if the design principles conflict with the idea of feng shui, it also brings a lot of negative qi and would hinder the success of work. Hence, careful study and incorporation of feng shui principles is necessary before applying to anything.

Literature Reference

Referencing my basic knowledge on feng shui from Charvátová and Xu’s text has greatly impacted on shaping the fundamental understanding of the origin of feng shui, historical significance and pushed my towards finding other examples. The two literature text I used were very helpful in exploring the compass tool, its use and how the tool has evolved over time and also gave a broader perspective on how feng shui was established in western world.

Bibliography

LHuillier, Rodney C. “The Ming Tombs Beijing.” Welcome to China. Last modified May 19, 2010. https://welcometochina.com.au/the-ming-tombs-beijing-366.html.

Hamilton, Nathan H. “Ming Tombs, 1987.” Flickr. Last modified January 31, 2016. https://www.flickr.com/photos/nat507/24375675899/in/photostream/.

National Library Board Singapore. “Suntec City.” National Library Board. Last modified April 11, 2024. https://www.nlb.gov.sg/main/article-detail?cmsuuid=0031a7ef-ebe2-4c42-af76-eaefeef60b10.

Mothership. “How feng shui is hidden in everyday Singapore design.” YouTube. July 21, 2022. https://youtu.be/TbNXm7D9FB4?si=xodw2CyMP9fUBsQc.

Xu, Ping. “‘FENG-SHUI’ MODELS STRUCTURED TRADITIONAL BEIJING COURTYARD HOUSES.” Journal of Architectural and Planning Research 15, no. 4 (1998): 271–82. http://www.jstor.org/stable/43030469.

Charvátová, Ivanka, et al. “Chinese Tombs Oriented by a Compass: Evidence from Paleomagnetic Changes versus the Age of Tombs.” Studia Geophysica et Geodaetica, vol. 55, no. 1, 2011, pp. 159–74, https://doi.org/10.1007/s11200-011-0009-2.