As I explored Asian art this semester, I became very interested in handscrolls and portraiture. My curiosity grew when our class visited the Lyman Allyn Museum and discovered works from Connecticut College’s own collection. I was intrigued by portraits of religious leaders. These pieces emphasize the purity and wisdom of each man’s soul by depicting them as gods. These works illustrate the principle of hitogami. Hitogami refers to a Shinto practice of worshiping virtuous men as gods during their lives or after their deaths. By examining these works, we can explore how deification was used as a political tool in medieval Japan and the legacy of hitogami in Japanese art. The religious blend of Shinto and Buddhist beliefs is a unique part of Japan’s culture. By studying traditional art inspired by religion, I hope to gain a deeper understanding of Japanese culture. The pieces I selected illustrate religious interactions between Japan and China during medieval Japan and inform viewers about Japan’s culture during the Middle Ages.

Historical Background:

I focused on art created in Japan’s medieval age. This era spanned from the mid-twelfth century to the mid-sixteenth. These were the Kamakura and Muromachi periods, respectively (Colcutt 2003). During this time, a warrior government took power. However, the old imperial court continued to assert their right to rule. They co-existed, but the old court and religious institutions faced a slow decline in their power and influence, and the shogun began to rise. These shogun were military feudal rulers who purported to serve the emperor. Different clans would gain and lose political control. However, the pattern of military leadership continued for centuries, and the aristocracy never recovered its full strength.

At this point in Japanese history, religion and state were closely entwined. The emperor was the most sacred figure in Japan and, at the same time, the pinnacle of political power. [DL: During Kamakura and Muromachi Japan, the true political power was in the hands of the shoguns/military generals, not the emperors.] His position connected religion with politics. Linguistic evidence also verifies this link. In Japanese, one word was used to describe political and religious rites: matsurigoto (Conlan 2016, 92). Having political authority meant possessing religious power, too, and vice-versa. Japan’s religion at the time was a blend of Shinto and Buddhism. Shinto divinities were thought to be avatars of Buddha (Casal 1959, 6). This unique blend of religion would continue until the Meiji restoration.

Summary of Sources:

I read Storytelling in Japanese Art to gain a basic understanding of Japanese illustrated stories and narrative techniques. The earliest scrolls created in Japan are copies of Chinese Buddhist sutra scrolls. Early biographies of historical figures echo sutras describing the Buddha’s life. Only the elite commissioned these scrolls. This source also details various formats and artistic styles. Over time, two artistic schools emerged. With the emergence of these two distinct styles, we see an indigenous, uniquely Japanese perspective in contrast to the more traditional Chinese style. The Tosa school focused on classic Japanese techniques, such as creating artificial flatness, and depicted subjects of Japanese folklore. The Kano school centered on Chinese lore and utilized Chinese realism in their scrolls.

Storytelling in Japanese Art also examines the significance of illustrated scrolls as historical documents explaining that handscrolls became fundamental instruments in authenticating the existence of deities and sacred sites. The passage about the Illustrated Legends of the Kitano Tenjin Shrine explored the life of exiled official Sugawara Michizane.

I studied When Men Become Gods: Apotheosis, Sacred Space, and Political Authority in Japan 1486-1599 to learn more about deification. In medieval Japan, the Ministry of Divine Affairs voted on posthumous deification [DL emphasis]. Most of the time, this deification was done out of fear of a vengeful spirit or “onryo.” The ministry hoped they could pacify the spirit by honoring it. However, there are some cases where apotheosis was done out of respect or admiration. Conlan details the arguments surrounding deification. He explains to readers that there are two schools of thought, that apotheosis was purely political or entirely religious. Conlan argues that deification was much more blended and was a mixture of these two reasons. Conlan analyzes one relatively unknown hitogami, Ōuchi Norihiro. I applied Conlan’s analysis of Norihiro to my study of other revered figures. Ultimately, the author concludes that influential political figures used their wealth to enact rites that united their followers into a community of shared belief.

My images

I studied both portraits and illustrated scrolls. My first selection of images focuses on deities in the Shinto pantheon. The Shinto deities reinforce their aristocratic descendants’ position in the political and social structure of medieval Japan. Then, I consider a prince whose apotheosis involved both Shintoism and Buddhism. The Shinto prince lent political legitimacy to the Buddhist temple he constructed thereby strengthening the bond between these two communities. Finally, I examine monks venerated and worshiped in the Buddhist tradition. Temples connected with these monks gained political and religious clout by highlighting mythical and virtuous leaders within their own community.

Handscrolls vs Portraits:

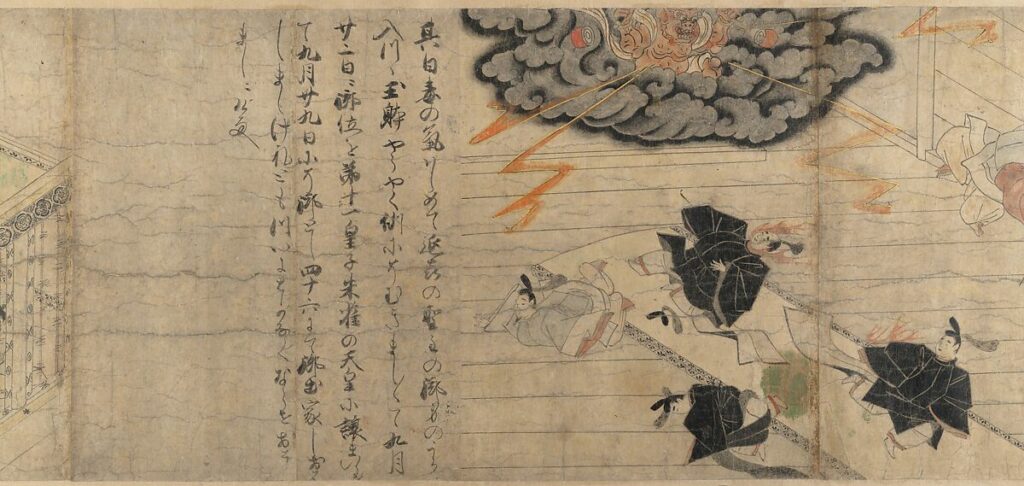

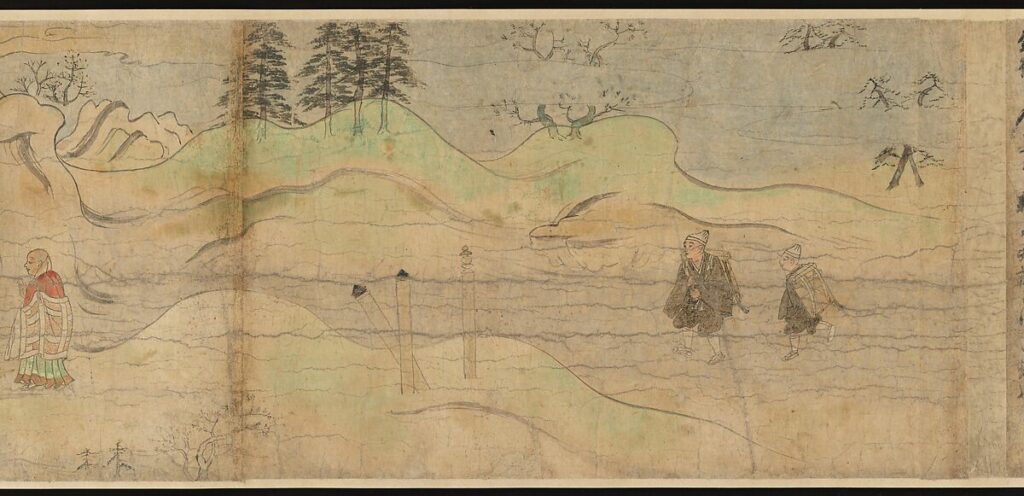

The tradition of the Japanese handscroll stretches back to the 8th century. They were commissioned only by those of high rank until the 17th century (Watanabe 2011, 29). The format of the scroll makes viewers physically experience the passage of time. The past is rolled away, the present is actively perceived, and the future is yet to be seen. Japanese illustrated scrolls are either in the episodic or continuous style. The scroll I’m focusing on, Illustrated Legends of the Kitano Tenjin Shrine, exemplifies the continuous style. There are long pictorial segments with minimal text. In continuous scrolls, motifs are often repeated to connect scenes. Mist and clouds are used as a frame to emphasize the important figures in each section. Rooms are shown roofless so viewers can see what’s taking place inside of a structure. This device invites viewers to consider multiple vignettes simultaneously. Continuous scrolls are narrative-focused.

Alternatively, portraits are less story-centered and instead emphasize the person they represent. They are meant to convey monumentality and disposition. In these portraits, it is more important to capture a person’s character traits than their likeness.

Handscroll with ink and gold leaf

11 5/16 in. × 22 ft.

Kamakura period, late 13th Japan

https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/45428?&pkgids=534&ft=*&offset=0&rpp=20&pos=1, Photo from the MET

This work is an illustrated handscroll, many scenes are shown. It tells the life story of Sugawara Michizane, a high-ranking official wrongfully exiled after his enemies slandered him at court. The scroll shows Michizane’s talent for poetry in childhood, his exile, the poetry he created, his death, and the events following his death. There is minimal writing. These images show the destruction and divine events surrounding Michizane’s death. In one scene, a thunder god brings destruction to the palace and kills four men. The god looks angry and is creating chaos. The men around him look very scared. Viewers feel the fear and confusion created after Sugawara’s death. This disorder is represented as the work of Michizane’s vengeful spirit. One of the men killed is Kiyotsura, the man who slandered Michizane (Borgen 1986, 308). This scene reminds viewers that the accusations against Michizane were lies, and the deceivers deserve punishment. The scroll serves as a warning to readers. Human society can not be harmonious and productive without exonerating those who were slandered.

The next image from the scroll I want to focus on is the plank. It’s said to have sprung up after Michizane’s spirit burned the palace to the ground. It’s inscribed with a poem by Michizane, detailing how he will destroy the palace until he’s avenged (Watanabe 2011, 53). While the events surrounding the scene are frightening, the pictorial representation itself looks calm. The background is peaceful, with depictions of nature and green and blue. To pacify Michizane’s onryo, Michizane is deified as the patron of writing and learning, and his angry spirit becomes calm. Honoring Michizane soothes his spirit and restores peace and balance to nature. Michizane’s descendants are absolved when Michizane is. Borgen argues that while these destructive events had a large part in creating the circumstances for Michizane’s apotheosis, Michizane’s sons’ return to court also affected the deification process. His descendants restored the Sugawara family name through their accomplishments (Borgen 1986, 314). This allowed the court to more easily deify Michizane, as his family had proved they were respectable. If his family had remained in exile or begun to act unscrupulously, the court might have had difficulty absolving Michizane. The Sugawara clan regained respect and were regarded highly, as they were close to a god. Officials who read the scroll would be reminded of this, and enemies would be reluctant to slander Michizane’s family again.

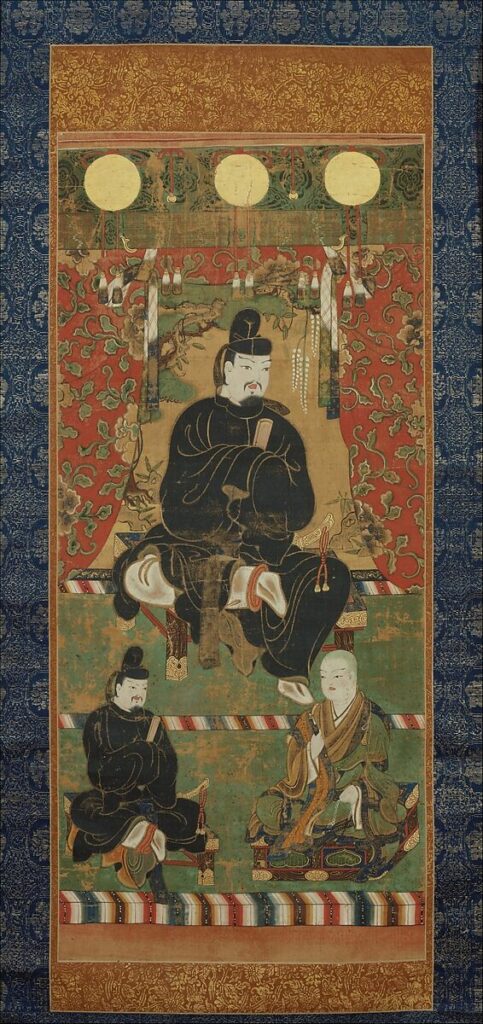

Hanging scroll; color on silk

34 x 15 in.

Nanbokuchō period, mid 14th century

https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/44847, Photo from the MET

Fujiwara no Kamatari is the most prominent figure in the scene, showing his importance. Behind him is a floral screen, adding a natural element to the portrait. This also reminds viewers of the families’ powerful wealth and ability to buy expensive art objects. The other two smaller figures have nearly identical faces to Kamatari, showing they are related. One of the more miniature figures is in an identical bureaucratic outfit as Kamatari. This illustrates that the family has continued to thrive in Japanese politics. Three moons hang above him, objects of divine worship. He is shown sitting in a shrine, with the curtains pulled back so viewers can see him. When Kamatari was first defied, he was an icon of the Kasuga cult, a uji cult, meaning only his family could worship him (Grapard 1992, 10). Then, as members of the Fujiwara family married into the imperial court, the Kasuga cult expanded to the royal sector. Worshiping Kamatari was an exclusive opportunity that only the elite had. The Fujiwara clan’s status would have inevitably risen because of the prominence and reputation of their mythical ancestors. Later, a new shrine was built, the Wakamiya Shrine, and the Kasuga cult opened to the public (Grapard 1992, 11). Kamatari would have gained more followers, further solidifying his family’s position within medieval Japan and strengthening their ties to the people of the region. This portrait was made in the 14th century, long after his deification. It would have reminded viewers of the Fujiwara clan’s connection to a god.

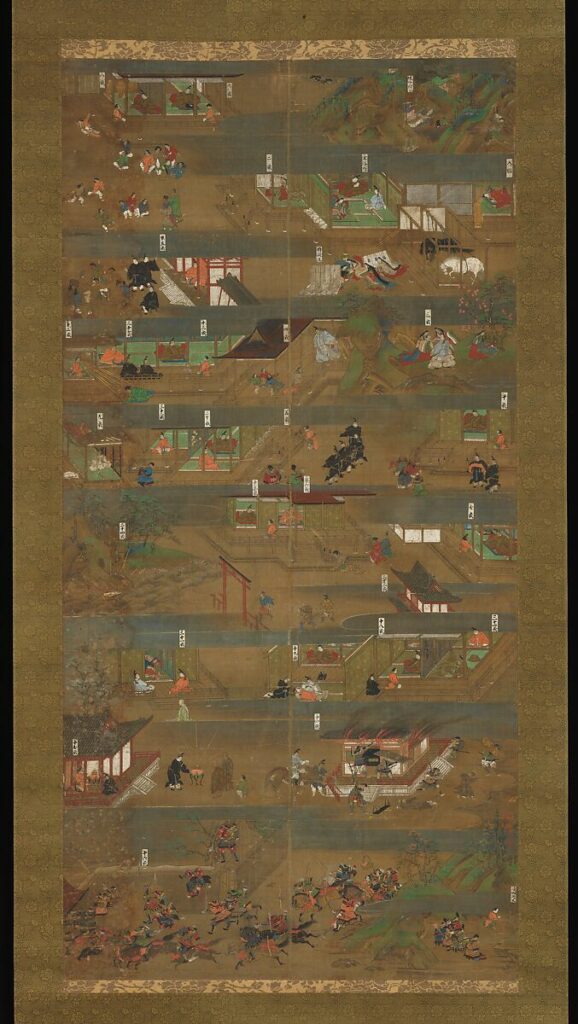

Hanging Scroll: Ink, Color, and Gold on Silk

67 5/8 x 33 1/4in

Kamakura period, 14th century

https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/45371, Photo from the MET

Although a hanging piece, this is not a portrait but various stories from Prince Shotoku’s life. Shotoku was an early advocate for Buddhism in Japan. These stories would have been more accessible for viewers because, unlike the heavily annotated scrolls, you do not need to be literate to understand the significance of the story. The scenes are shown in random order instead of chronologically, making viewers feel like they’re seeing the exciting deeds of a great hero instead of a simple biography. The style is also similar to a Buddhist sutra (Watanabe 2011, 4). Created in the 14th century, the hanging work depicts familiar architecture and dress from the 12th century, despite the fact that Prince Shotoku lived in the 8th century. Viewers would have felt more connected to Prince Shotoku because they recognized the surroundings. These alterations reveal the piece was meant to be easily understood by its audience. It cultivates an appreciation of Shotoku and his work spreading Buddhism in Japan. Although Shotoku expanded Buddhism, his family initially deified him in the Shinto pantheon. Later, he was thought to be the Bodhisattva Kannon (Carr 2012, 14). Those who knew Shotoku while he was alive would have gained higher spiritual status and been able to claim they were companions of a bodhisattva. This would have given their monastic lineage more weight in court.

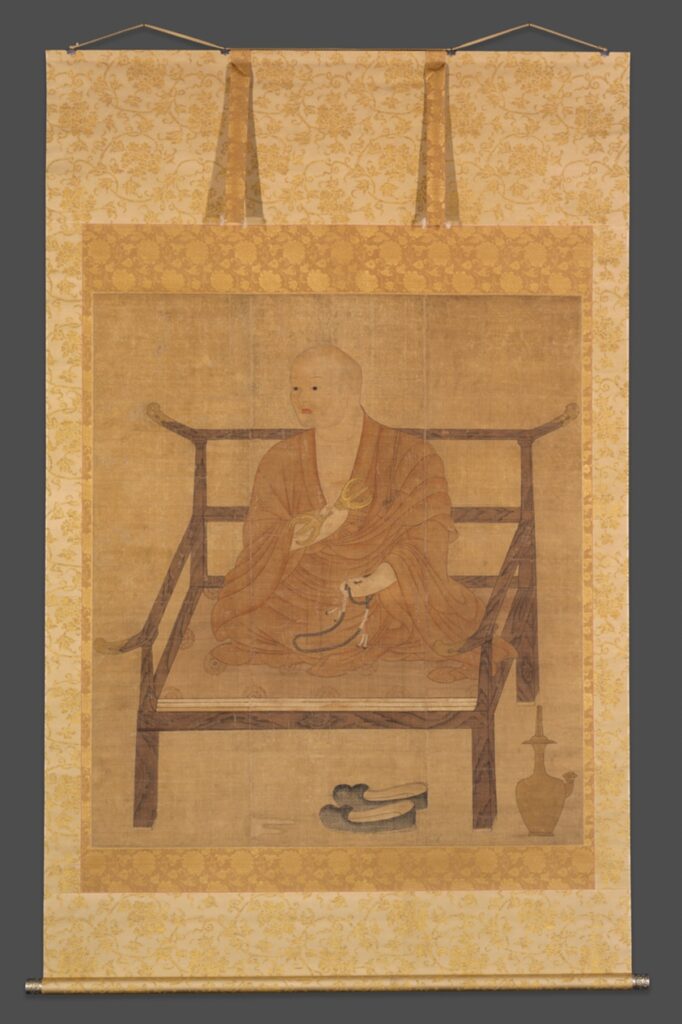

Hanging scroll; ink and color on silk

59 1/4 x 30 1/4 in

Kamakura period, 14th century

https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/45238, Photo from the MET

Hanging scroll; ink and color on silk

48 3/4 x 29 1/4 in

Kamakura period, 14th century

https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/45372, Photo From the MET

Jion Daishi is the portrait of a venerated monk. Jion shows all the signs of a holy monk, with his head shaved and wearing a brown robe and cloth with block nature scenes shown. This garment could show Jion’s wealth; however, it serves as a reminder of Jion’s mentor. In a portrait of Xuanzang, Xuanzang wears a very similar print. Xuanzang was a revered Chinese Buddhist monk who translated Buddhist scripture and was thought of as the patriarch of the Hossō sect of Buddhism in Japan. Jion was a student of Xuanzang, who spread Hosso Buddhism in Japan. This connection would have been meaningful in illustrating the legitimacy and religious lineage of the temple that displayed Jion portrait. Just as Jion Daishi’s religious ideology was influenced by Chinese thought, his painting exhibits Chinese Tang techniques. The image is in the archaic line style, and the figure almost jumps out, which is very visually engaging. By creating an illustration of Jion with no background, viewers’ focus is centered on him. Viewers also see the monk holding prayer beads, furthering his religious image. This image is meant to show Jion’s character rather than a physical resemblance. It would have been displayed during memorial rituals. This portrait shows followers the temple’s heritage of extraordinary deeds. This illustrious religious ancestry reinforced the temple’s place in Japan.

Hanging scroll; ink, colors, and gold on silk

51 × 46 in

Kamakura period, 14th century

https://www.artic.edu/artworks/11548/portrait-of-kobo-daishi-kukai, Photo from the Art Institute of Chicago

This portrait of Buddhist saint Kobo Daishi emits a pious energy. The monk is shown in a simple brown robe. He holds a Buddhist prayer necklace in one hand and in the other a Three-Pronged Vajra, a symbol of Shingon Buddhism, which he is the founder of. His head is shaved to show Kobo has given up a worldly ego. This devout image represents Kobo’s traits in life. He was an enormously influential figure in Japanese Buddhism, with many temples honoring him (Casal 1959, 131). Not only is he well respected, but people believe him to be divine. It is said that he never died and is just sleeping until the future Buddha appears (Casal 1959, 139). His saintly status and magical deeds legitimize all temples connected with Kobo. Those who studied under him can show their connection to this famous figure, and their temple will gain a more profound respect for having ties to Kobo. Those whose lineage tied them to a transhistorical figure could effectively claim greater salvational efficacy (Carr 2012, 11). If Kobo had been involved in the temple and had become a saint, it encouraged followers to join the same temple so they, too, could become blessed.

Conclusion

The creation of hitogamic images emerged at a time when the aristocracy and political institutions were in decline. Political leaders of this period attempted to reaffirm the legitimacy of their rule by asserting ties to mythical and celebrated ancestors. Images surrounding hitogami reminded people of a time before the new warrior-ruled Japan.

Bibliography

Borgen, Robert. Sugawara No Michizane and the Early Heian Court. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1986. https://hdl.handle.net/2027/heb00217.0001.001. PDF.

Carr, Kevin Gray. “Ways to Tell a Sacred Life: HAGIOGRAPHIC IMAGINATION IN MEDIEVAL JAPAN.” In Plotting the Prince: Shōtoku Cults and the Mapping of Medieval Japanese Buddhism, 23–46. University of Hawai’i Press, 2012. http://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt6wqmhv.7.

Casal, U.A. The Saintly Kobo Daishi in Popular Lore: A.D. 774-835, 1959.

Colcutt, Martin. “About Japan: A Teacher’s Resource | Japan’s Medieval Age: The Kamakura & Muromachi Periods | Japan Society,” n.d. https://aboutjapan.japansociety.org/content.cfm/japans_medieval_age_the_kamakura__muromachi_periods#sthash.LAItdAeU.nIoQLYVC.dpbs.

Conlan, Thomas. “WHEN MEN BECOME GODS: APOTHEOSIS, SACRED SPACE, AND POLITICAL AUTHORITY IN JAPAN 1486-1599.” QUAESTIONES MEDII AEVI NOVAE, 2012, 89–104. https://www.academia.edu/41965202/WHEN_MEN_BECOME_GODS_APOTHEOSIS_SACRED_SPACE_AND_POLITICAL_AUTHORITY.

GRAPARD, ALLAN G. “Introduction.” In The Protocol of the Gods: A Study of the Kasuga Cult in Japanese History, 1st ed., 1–14. University of California Press, 1992. https://doi.org/10.2307/jj.2392282.6.

Watanabe, Masako, and Marcie M Muscat. 2011. Storytelling in Japanese Art. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art.