Introduction

Concepts and ideas are of the most malleable human inventions. Nothing stays the same over time; new forests grow and some burn, continents shift, species exist and go extinct, buildings deteriorate, religions and languages form and split, human innovation is permanently ever-changing. Buddhism is an ancient practice that has faced thousands of years of changing human populations, bringing with them new beliefs, needs, and approaches. This article explores the various ways in which Buddhist monastery architecture has absorbed such crucial changes over time. This article intends to answer questions such as: How has traditional Buddhist architecture influenced modern/ contemporary design choices? And, in what ways have traditional intentions of Buddhist monasteries changed to adapt to current-day needs and priorities? Through a collection of case studies, examples of ancient monasteries with continued traditional use are included, as well as ancient monastery sites that have drastically evolved over time into their current contemporary forms. Finally, an exploration of worldly Buddhist temples and educational spaces are represented as a way to exhibit the current-day priorities and design choices of Buddhist gathering spaces.

The Guangji Temple: A Traditional Representation

The first example dedicated to this article is a case study that envelopes a traditional approach to Buddhist monasteries. The Guangji Temple of Universal Rescue (Figure 1) is a monastery located in the Xisi district of Beijing. The original structure was founded at the end of the Song Dynasty but was destroyed in a war; the present structure was built during the late Ming Dynasty and was named by the Chenghua emperor in 1484 (Fisher, “Religion,” p. 349, 2012). Today, following the rise of the Chinese Communist government in 1949, the temple is the headquarters of the Chinese Buddhist Association; a government-sanctioned branch for Buddhist monastics of which directly report to the Religious Affairs Bureau of the central government (Fisher, “Religion,” p. 349, 2012). The overall arrangement of the temple is symmetrical; the medial axis include important buildings such as the Temple Gate, the Main Hall, the Sutra Hall, and the “Jade Carving Monk Status Attaining Altar,” from south to north (China Culture; Religion; Buddhist Temples). The Guangji Temple participants strive for traditional Buddhist rituals as a way to take ownership of certain practices lost and severely limited during the rule of the Maoist government (Fisher, “Religion,” p. 352, 2012).

Devotees are temple-goers who pray to or meditate before images of Buddhas and bodhisattvas in the temple. The inner courtyard of the temple allows for a ritual circuit in which devotees may visit each of its main images: the bodhisattva Maitreya (the future Buddha) at the Hall of Heavenly Kings, which marks the main ritual entrance to the inner courtyard; then continues to the image of the bodhisattva Skanda who stands at the rear of the same hall; a large incense urn facing the main hall; then on to the images of historical Buddha, Shakyamuni; and finally towards an image of the bodhisattva Guanyin in the rear-most temple hall (Fisher, “Religion,” p. 350, 2012). Sutra chanters also participate in this ritual circuit; their activities involve a series of praises to many Buddhas and bodhisattvas within the temple. Both the devotees and sutra chanters engage in activities that have been common in Chinese Buddhist temples for hundreds of years. Preacher circles and discussion groups gather in the temple’s outer courtyard. Although today the devotees’ and sutra chanters’ practices are further rooted in traditional Chinese Buddhism, the circles and discussion groups follow a more contemporary teaching of China’s more contemporary narratives as a way to create “moral frameworks relevant to their listeners’ present-day lives,” (Fisher, “Religion,” p. 354, 2012). Additionally, since the 1980s, the temple has opened its two southernmost courtyards, including its main halls, to the public during the daytime for free (Fisher, “Religion,” p. 354, 2012). This type of approach of using the Ming dynasty-dated temple to perform traditional practices while also celebrating the contemporary approach to Buddhism has been a large attraction for tourism as well (China Culture; Religion; Buddhist Temples).

The Leifeng and Porcelain Pagodas: Evolving Legends

The following couple of case studies have less to do with architectural and cultural adaptive reuse of Buddhist monasteries and relate more along the lines of complete contemporary transformations and replacements of traditional Buddhist temples.

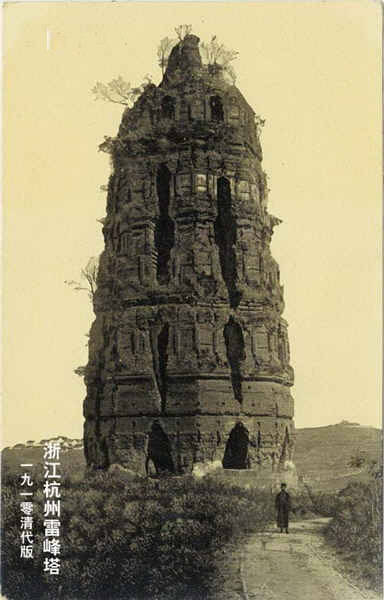

The historical site of the Leifeng Pagoda refers to the remaining collapsed ruins of the original pagoda which was built dating back to the end of the Five Dynasties (907-960 CE) (Zhejiang, “The Five Dynasties,” p. 19, 2003). Located on Sunset Hill south of the West Lake in Hangzhou, Zhejiang, China, this historic cultural site has faced a series of evolving functions. The original pagoda was a traditionally octagonal, five-story structure built of brick and wood (Hangzhou, Cultural Tourism). The pagoda experienced two suffrages of damage between the Song Dynasty and Ming Dynasty; the first round of damage occurring during the Song Dynasty due to war and the second during the Ming Dynasty in which pirates invaded Hangzhou and burned down the wooden elements of the tower (Zhejiang, “The Five Dynasties,” p. 19, 2003). In the ruins of the tower stood a brick skeleton that was weakened over time due to looting and excavation (Figure 2); the tower’s brick ruins could no longer serve a religious function but instead represented a superstitious medicinal power. The bricks were believed to fend off evil spirits, prevent miscarriage, and repel illness (Hangzhou, Cultural Tourism). Due to the intemperate looting, the ruins of the original Leifeng Pagoda eventually collapsed on September 25, 1924 (Zhejiang, “The Five Dynasties,” p. 19, 2003). Already, this site had faced a transition between religious function into a functional resource, and ultimately to as a historical archaeology site. This is not how the story of Leifeng ends, though; in 1988, Chinese organizations, including the Hangzhou Tourism Economics Association, came together to promote the reconstruction of the Leifeng Pagoda in support of the “Hangzhou City Master Plan” project (Hangzhou, Cultural Tourism). In 2002, the newly reconstructed Leifeng Pagoda (Figure 2.1) opened on top of the ruins of the original temple. Today, as seen in Figure 2.1, the pagoda stands as a five-story octagonal tower composed of 1,400 ton steel structure including 200 tons of copper parts, sightseeing elevators, air conditioning, television, speakers, and escalators. This composition of evolutionary functions is important to consider when analyzing the contemporary idea of Buddhist monasteries. In this case, as mentioned earlier, the Leifeng Pagoda adapted under the influence of what was important and relevant at the time whether that has been religion, monumentality, remedial, archaeologically and culturally representative, or, as it stands today, an economic functionality and tourist destination.

The Porcelain Tower

The following section on the Porcelain Tower pulls from theories of historical reconstruction in Pengfei Ma et al.’s article, “The Resurrecting Urban Heritage with Contemporary Adaption: The Reconstruction of the Porcelain Tower in Nanjing (China).” Reconstruction design is argued to be in urban heritage as an adaptive approach to creating a “continuous cultural dynamic for urban regeneration (Ma, et al., “Resurrecting,” 2012). The article studies the reconstruction of the Porcelain Tower as a way of urban cultural regeneration through a rebuilding of heritage. The theme of authenticity is explored through the questioning of the nature of the new Porcelain Tower; does celebrating heritage involve historical conservation or should it evolve with the times and priorities of the current-day city it belongs to? This article shed light on and helped theorize the art of reconstruction and the delicate process that follows such projects.

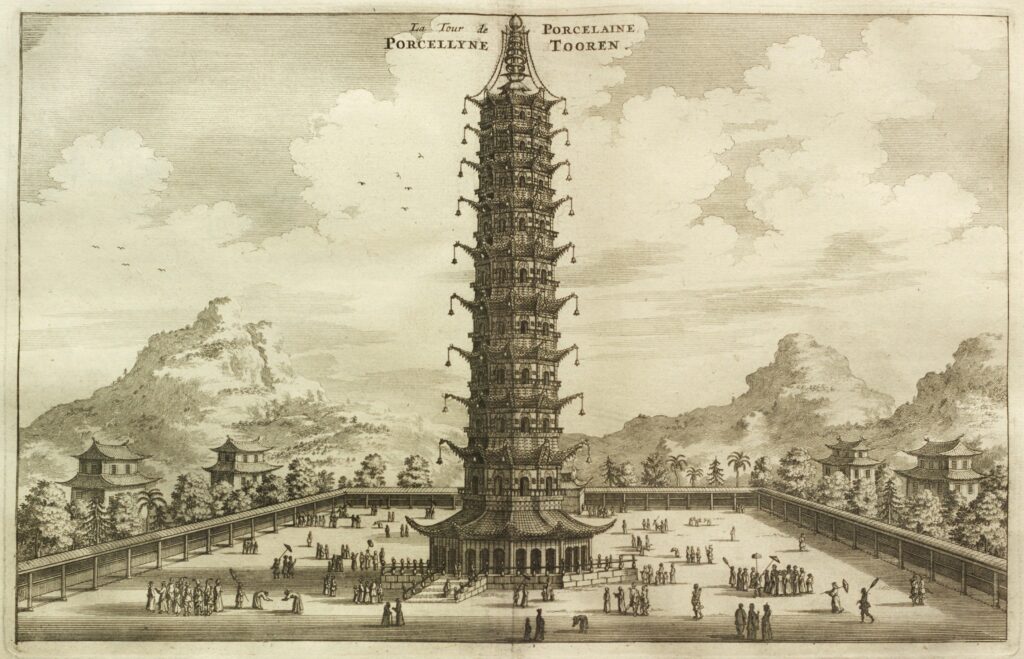

This case study of the Porcelain Tower builds on the story of the Leifeng Pagoda in its narrative of architectural contemporization. The original Porcelain Tower of Nanjing, also called the Great Bao’en (Figure 3), was a royal building designed by Emperor Yong Le of the Ming Dynasty and took 15 years to build (1413-1428 CE) (Ma, et al., “Resurrecting,” 2012). Located on the south bank of the Qinhuai River, the octagonal glazed-brick temple was built nine stories, standing 261 feet high and 97 feet wide and was considered the center of Buddhism in China at the time (Ma, et al., “Resurrecting,” 2012). Despite this culturally Chinese and Buddhist-related importance, the tower was famously idolized and exploited by the West. European travelers like Johan Nieuhof visited the Porcelain Tower, listing it as one of the “Seven Wonders of the World,” (Ma, et al., “Resurrecting,” 2012). The tower additionally became the archetypical Chinoiserie building plan to imitate throughout 18th-century Europe (Ma, et al., “Resurrecting,” 2012). By the time of its unfortunate destruction in the Taiping Rebellion of 1856, the central functions of the tower had pivoted away from just Buddhism and had become a, “symbol of royal power, a religious monument, and a magnificent architectural spectacle that could rival any other around the world,” (Ma, et al., “Resurrecting,” 2012).

Today, urban regeneration is happening all around us. Yet, the question of how to continue a particular location’s history and heritage within that regeneration is an important one to ask. When considering historically rich cities such as Nanjing, the, “preservation and continuation of what we already have, know, value, and cherish ranging from cultural texts and objects to buildings and monuments that are deemed worthy of being preserved to have a future,” (Assmann, “The Future,” p. 28, 2019). Having opened in 2015 with its modern steel and glass appearance, today’s Porcelain tower rejects any call for material authenticity (Figure 3.1). Instead of approaching the project with a traditional restoration project involving materials of heritage and philological restoration, an innovative angle through the use of a concrete, steel, and glass body was taken in the “reconstruction” of the Porcelain tower. Artifactual materials such as broken brickwork and tiles are exhibited inside of the contemporary museum as a way to continue the legacy of the original tower (Ma, et al., “Resurrecting,” 2012). This case study brings forward the questions of: was this approach to reconstruction disrespectful to the original tower and history? Or is this type of refashion what contemporary society calls for today?

Worldly Buddhist Contemporization

So far, the case studies discussed have involved examples of historic temples that continued to be used today with traditional approaches as well as moderate contemporary introductions. Additionally discussed examples involve historic pagodas that have undergone dramatic contemporary “restoration” processes that leave traditional sites with new structures and modern-day practices of tourism and non-Buddhist-central practices. The following examples illustrate additional approaches to the contemporization of Buddhist monasteries in Australia; a newly built monastery used for religious and educational purpose and an educational Buddhist institute that has partnered with the prior monastery. Finally, a brief exploration of a new Buddhist monastery in Taiwan that has incorporated modern design while respecting religious tradition and the history of its site.

The Nan Tien Temple

The following section on the Nan Tien Temple pulls from Gordon Waitt’s essay, “Locating a Buddhist Temple in Wollongong, New South Wales (Australia),” in which the nature and setting of the Nan Tien Temple are examined. The essay explores the origins of Nan Tien and the organization it was formed under as well as the reasoning for choosing Wollongong as the location for the largest Buddhist temple in the southern hemisphere. Through the study of Buddhist populations throughout Australia, the influence of Master Hsing Yun, and the cultural and economic revitalization of Wollongong brought by Nan Tien, this article sheds light on the worldly Buddhist architectural narrative.

In October of 1995, Grand Master Hsing Yun hosted the opening ceremony of the Nan Tien Temple in Berkeley, Wollongong, New South Wales, Australia (Rocha, Barker, “Buddhism,” 2010). The site is considered to link heaven and earth and the complex is referred to as a “pure land on earth,” (Figure 4),(Rocha, Barker, “Buddhism,” 2010). For years the original open-field site was one of vacancy and industrial structures; today, the temple’s gates, its Buddha statues, and Chinese palace-style architecture visually introduced a new narrative to the site that contrasts sharply with industrial sheds, power cables, and a passing freeway. The Nan Tien Temple (Figure 4.1) incorporates modern architectural techniques while also including traditional prayer spaces such as the “Great Mercy Shrine” and the “Great Hero Hall,” as well as an eight-story pagoda, front hall houses, and the main hall in the back houses. Both halls hold thousands of small statues of Buddha along the walls. The pagoda is traditionally Chinese-Buddhist-style with flying eaves while the main temples incorporate Tibetan monastic architecture. The courtyards feature Japanese-style gardens while statues incorporate bright South-East Asian color schemes (Rocha, Barker, “Buddhism,” 2010).

While the temple has an eclectic approach in celebrating traditional architecture, the temple was designed and built by Australian architects and construction workers and includes meeting rooms, a museum, conference facilities and a restaurant (Rocha, Barker, “Buddhism,” 2010). The temple is one of the worldwide 120 branch temples that comprises the Taiwanese “Fo Guang Shan” Buddhist order, founded in 1967 by Hsing Yun (Rocha, Barker, “Buddhism,” 2010). The vision of Fo Guang Shan led by Hsing Yun leads with a narrative of “Humanistic Buddhism,” outreaching globally to locations in need of representation for minority-religions; 26 countries, including Canada, Hong Kong, Malaysia, the Philippines, and the United States. Australia has a large population of Asian immigrants, many of whom are also Buddhist. Historically in New South Wales, issues of heightened racism, particularly against those practicing Islam, Hinduism, and Buddhism have made the need for safe sacred spaces all the more pressing. When decisions over the new temple’s location were being discussed, over 140,000 Buddhists resided in Australia, 59,000 of whom lived in New South Wales (Rocha, Barker, “Buddhism,” 2010). Despite the societal isolation of Wollongong, it was ultimately decided as the site location for Berkely’s “feng shui” elevated location in Mount Kembla (Rocha, Barker, “Buddhism,” 2010). This new vision of the Australian multicultural national identities inspired leaders of Wollongong’s Christian ministries to extend an inclusive welcome to Buddhists in Wollongong. It became widely accepted that Nan Tien would create not only a place of Buddhist worship, education, and pilgrimage but also aided the revitalization of the local economy by attracting tourism and community diversity.

The Nan Tien Institute

The Nan Tien Institute (Figure 5) was established in 2011 as a center for Humanistic Buddhism education. The Institute offers several graduate programs and Humanistic Buddhism is now officially included as part of the Australian higher education system (Bau, “A Letter,” p.173, 2019). The Institute caters to around 3,000 students and 360 staff and was established on top of a retired landfill (McIntosh, Barthelmess, “Remediation,” p.1, 2012). A pedestrian bridge, the Nan Tien Bridge, connects the Nan Tien Institute and Nan Tien Temple as the two sites partner in light of education and religious ceremony. The footbridge has a further symbolic significance: it links the east (the Temple) with the west (the Institute) while also connecting the Temple’s spiritual practice with the Institute’s academic focus (Juewei, “A Buddhist-Informed,” 2022). With its organic shape and bending, protruding exterior walls, the Institute itself was designed to depict a lotus; a Buddhist symbol for the purifying process as one “rises above muddy waters of worldly attachment.” It is also noted that the architects may have approached this symbolism through the idea that the building was quite literally built atop an old “muddy” landfill (Juewei, “A Buddhist-Informed,” 2022). The building has large, rounded glass windows to let in as much light as possible throughout the day and allow for the sun’s path to be as expressive as possible to “remind inhabitants of the truth of impermanence,” (Juewei, “A Buddhist-Informed,” 2022). The interior provides opportunities for students and staff to participate in Buddhist practices; the meditation hall and learning spaces allow for quiet reflection and ritual practice. The building includes a variety of materials including wood, concrete, glass, and steel, most of which were not traditionally used but are an appropriate transition for the contemporary functions of the space. The partnership between the Nan Tien Institute and neighboring Nan Tien Temple is a strong example of how Buddhist monasteries have evolved into relevant needs and issues in today’s societies; prioritizing education while simultaneously devoting resources to creating safe and celebratory spaces for Buddhist ritualistic practices.

Water-Moon (Nung Chan) Monastery, Taipei, Taiwan

When visiting the Keelung River-facing Water-Moon Monastery in Taipei, Taiwan (Figure 6), it is not necessarily recognized as a Buddhist temple for spiritual practice, but rather as a “dazzling contemporary art museum,” (Qingxiang, “Inspection Notes,” p.35, 2013.) Over time, the ridged roofs of contemporary Buddhist monasteries have gradually eased; in the past twenty years, the sloped roof style has popularly come to a full flat top. Except for the gate archway, which still includes some traditional architectural features, the appearance of Water Moon has subverted from traditional Chinese style; no sloping roof, vertical ridges, nor decorative interior elements such as dragon pillars and stone lions. The use of physical symmetry is also abandoned as can be seen with the front facade of the monastery and its three small lotus ponds within the larger pond (Qingxiang, “Inspection Notes,” p.38, 2013). Similar to the Fo Guang Shan Buddhist order (of which Nan Tien was founded under), the Dharma Drum Mountain (DMM) is a Taiwanese Buddhist order that celebrates contemporary continuations of Buddhism and has chapters of Buddhist temples and schools throughout Taiwan and the U.S. Master Shen Yun founded the organization, and in 1977 took over management of what was the Water-Moon (Nung Chan) site at the time, a two-story farmhouse (Ju, “The Water-Moon,” 2013). As the institute and temple outgrew the farmhouse over the years, Nung Chan was declared a historic site in 2004 in order to preserve the original farmhouse while also allowing the opportunity for a new and larger temple to be built. Master Sheng Yen hired architect Kris Yao, a follower of Tibetan Buddhism, to design the new temple of Nung Chan (Ju, “The Water-Moon,” 2013). At the time, Taiwanese Buddhist temples weren’t considered more than spaces to conduct religious rituals; Master Sheng Yen wanted to create a multipurpose temple of gathering. Water-Moon was completed in 2012, and sits back along an 80-foot long and 40-foot wide lotus pond. An L-shaped structure contains the complex’s Chan and Dharma Halls that link to the back of the main hall; expansive rectangular halls of which Yao hoped to emit the original farmhouse’s elements with a simple, humble, and organic design. (Ju, “The Water-Moon,” 2013) Master Sheng Yen claimed to have seen his vision of the temple while meditating as a, “Flower in Space, Moon in Water… Let’s name it the Water-Moon Monastery,” (ArchDaily, “Mater-Moon” 2013). On the interior, an open fretwork facade allows the “light of the Buddha (Yao)” to shine through and illuminate walls with Buddhist text. Similar to that of the Nan Tien Institute, Yao added a Heart Sutra facade to the west side of the main hall to allow light to shine through and continue this sense of impermanence in contrast to the building’s solidity (Ju, “The Water-Moon,” 2013). The Water-Moon Monastery focuses less on the traditional sole use of religious functionality and more on the experience; encouraging visitors to embrace life in both dark times and light, move through large halls, and observe the muted color scheme of concrete intended to reflect the simplicity of Zen Buddhism.

Conclusion

It is fascinating to explore the ways Buddhist architecture has absorbed the ever-changing societies it has grown throughout. This collection of Buddhist temples exhibits the ways Buddhist monasteries have adapted throughout time to their ultimate forms today. Buddhism supports the journey individuals take to reach personal enlightenment; this article has presented a series of studies in which cultural enlightenment has been architecturally reached through the continuation of tradition, reconstructions of heritage, economic prosperity, and education, all the while celebrating a long history of Buddhist monastic architecture.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Assmann, A. “The Future of Cultural Heritage and Its Challenges,” Cultural Sustainability: Perspectives from the Humanities and Social Sciences; Meireis, T., Rippl, G., Eds.; Abingdon Oxon: New York, NY, USA, 2019; pp. 25–35. ISBN 9780815357544

Bau, Hsing, “A Letter to Dharma Protectors and Friends,” Fo Guang Shan Institute of Humanistic Buddhism, 2019. https://buddhism.lib.ntu.edu.tw/FULLTEXT/JR-MAG/mag582279.pdf

陳清香 (Chen Qingxiang), “農禪寺水月道場巡禮記 (Inspection Notes on Shuiyue Dojo of Nongchan Temple,” 慧炬 (Torch of Wisdom Monthly) 581 (2013): 35-40. https://buddhism.lib.ntu.edu.tw/FULLTEXT/JR-MAG/mag390302.pdf

Fisher, Gareth, “Religion as Repertoire: Resourcing the Past in a Beijing Buddhist Temple,” Modern China, 38(3), (2012): 346-376. https://doi.org/10.1177/0097700411417327.

Hangzhou, Leifeng Pagoda Cultural Tourism Development CO., Ltd Zhejiang ICP No. 110095. http://jing.leifengta.com/introduction.aspx?c_kind=4&c_kind2=15&c_kind3=18&c_kind4=25#maodian

Ju, Sam. “Kris Yao’s Architectural Revelation: The Water-Moon Dharma Center at Nung Chan Monastery.” Taiwan Panorama Magazine, December 2013. https://www.taiwan-panorama.com/en/Articles/Details?Guid=a1c6decd-f143-4510-93b0-5cc4ac0cc5d1&CatId=7&postname=Kris+Yao%E2%80%99s+Architectural+Revelation-The+Water-Moon+Dharma+Center+at+Nung+Chan+Monastery.

Juewei, “A Buddhist-Informed Institution of Higher Education in Australia.” Oxford Public Philosophy, August 17, 2022. https://www.oxfordpublicphilosophy.com/blog/ppt-nan-tien-institute.

Ma, Pengfei, Li, Mengbi, and Li, Xiangning, “Resurrecting Urban Heritage with Contemporary Adaption: The Reconstruction of the Porcelain Tower in Nanjing (China),” Land 11, 2012, no. 7: 978. https://doi.org/10.3390/land11070978

McIntosh, G.W., Barthelmess, A.J., “Remediation of an Old Landfill at Unanderra, NSW,” Douglas Partners Pty Ltd, 2012. https://web.archive.org/web/20170217012058id_/http://rienco.com.au/papers/1445922699_UOW%20paper_McIntosh_FINAL.pdf

Rocha, Cristina, Barker, Michelle, “Buddhism in Australia: Traditions in Change,” Routledge Critical Studies in Buddhism, illustrated, Routledge 2010. https://books.google.com/books?id=XohdBwAAQBAJ&lpg=PA74&ots=BFRWx_R8Kj&dq=nan%20tien%20temple&lr&pg=PP1#v=onepage&q=nan%20tien%20temple&f=false

Zhejiang Provincial Institute of Antiquity and Archaeology,. “The Five Dynasties Underground Chamber of Pagoda Leifeng in Hangzhou” Chinese Archaeology 3, no. 1 (2003): 19-26. https://doi.org/10.1515/CHAR.2003.3.1.19.

IMAGE CITATIONS

“Guangji Temple (Beijing),” Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Guangji_Temple_(Beijing)#/media/File:Guangji_Temple_Main_Garden.jpg

“Leifeng Pagoda,” Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Leifeng_Pagoda#/media/File:Leifeng_Pagoda_1910.jpg,

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Leifeng_Pagoda#/media/File:Leifeng_Pagoda_DJI_0593_(2).jpg

“Porcelain Tower of Nanjing,” Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Porcelain_Tower_of_Nanjing#/media/File:UB_Maastricht_-_Nieuhof_1665_-_Toren.jpg, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Porcelain_Tower_of_Nanjing#/media/File:Porcelain_Tower_of_Nanjing_-_Night_View.jpg

“Nan Tien Temple,” Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Nan_Tien_Temple#/media/File:Looking_over_temple_in_berkley.jpg, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Nan_Tien_Temple#/media/File:1.-Nan_Tien_Temple_front.jpg

“Nan Tien Institute,” Wikipedia. https://simple.wikipedia.org/wiki/Nan_Tien_Institute#/media/File:Nan_Tien_Institute.jpg