The tale of Kiyohime and Anchin has been used to justify the Buddhist belief that “women have little inclination toward enlightenment in the next world, but deep reserves of jealousy and evil sexual desires” (Shimazaki 162). The depiction of Kiyohime, especially when it is done by male artists, serves as an insight into Japanese society’s opinion of angry women at the time of the piece’s creation. One constant in all portrayals of Kiyohime is that as she gets more inflamed, her appearance becomes more bedraggled and less beautiful. As beauty in women was and still is highly valued in Japanese society, the association between Kiyohime’s anger and appearance serves to lessen her humanity as the tale continues. Her loss of beauty symbolizes her loss of humanity throughout her transformation.

According to Japanese mythology, Kiyohime, whose name translates to “pure lady,” was the daughter of a nobleman during the reign of Emperor Daigo. In the year 928 CE, Kiyohime fell in love with a handsome Buddhist priest named Anchin who was traveling through her town. However, Anchin was sworn to celibacy and could not return Kiyohime’s affections. Once he discovered her feelings, Anchin promised he would visit her, but fled to the Dōjō-ji temple instead. Upon learning of his deception, Kiyohime ran after Anchin. Eventually, she caught up to him at the Hidaka River, but Anchin hired a ferryman to carry him across, forcing Kiyohime to swim across the river without a boat. As she swam, Kiyohime’s rage grew greater and greater, eventually transforming her into a vengeful dragon. With the help of some monks, Anchin hid from Kiyohime in a bonshō, or temple bell. However, with her newly powerful nose, Kiyohime smelled Anchin and wrapped herself around the bonshō, breathing fire onto it until he burned to death inside. Consumed by grief at the loss of both her love and of her own humanity, Kiyohime kills herself.

Before moving on to the collection, some vital motifs to keep note of are the significance of the patterns on Kiyohime’s kimono, as well as the way the artists choose to portray Kiyohime’s mutation, whether it be through a literal depiction of transformation or through visual metaphors.

Creator: Unknown

Period: Muromachi

Date: 1400

Culture: Japan

Medium: scroll painting; ink and color on paper

These segments from the Dōjō-Ji Engi Emaki show the complete transformation of Kiyohime from a woman into a dragon. As Anchin runs further from Kiyohime, the greater her anger becomes, and the more serpentine she becomes. The first section begins with Kiyohime first entering Anchin’s temple, reaching her hand in a plea for him to stop running. As he continues to flee from her affections, her anger is first materialized in firebreathing before she begins to transform into a serpentine dragon. The second section shows Kiyohime searching for and finding the hiding Anchin, and finally burning Anchin alive inside the temple’s bonshō as her final revenge.

Creator: Toyohara Kunichika

Era: Meiji

Date: 1887

Culture: Japan

Medium: woodblock print; ink and color on paper

Dimensions: 70 x 34.5 cm

This triptych portrays the moment as the boatman Namiroku rows Anchin across the Hidaka River, leaving Kiyohime behind. The specific depiction is of Kiyohime as played by the kabuki onnagata actor Nakamura Fukusuke. In the third panel of the triptych, behind the boatman, only Anchin’s ear and part of his hat are visible as he hides from Kiyohime. This scene takes place when Kiyohime is still fully human; however, Kiyohime’s kimono has a pattern of triangles and sakura blossoms, and in kabuki, a triangle-patterned kimono symbolizes serpentine scales. Sakura blossoms are also a symbol of ephemeral or fallen beauty. This imagery is important in the story of Kiyohime, as she was a beautiful noble lady before her anger corrupted her.

Series: One Hundred Ghost Tales from China and Japan

Creator: Tsukioka Yoshitoshi

Period: Edo

Date: 1856

Culture: Japan

Medium: woodblock print; ink and color on paper

Dimensions: 34.61 × 23.02 cm

Repository: Los Angeles County Museum of Art

Here, Kiyohime emerges from the Hidaka River, having swum across it in pursuit of Anchin. As she squeezes her hair dry with two hands, she gnaws one strand in her mouth in anxious frustration. This depiction of Kiyohime’s kimono keeps constant the sakura blossom motif, with sakura blossoms both on Kiyohime’s kimono and raining down from the top left corner of the print. Additionally, this portrayal adds waves to the kimono to symbolize her journey through the river. In contrast to the last triptych, Kiyohime’s appearance here is much more disheveled. Her posture is slouched, her kimono is falling open, and her hair falls slack over her shoulders and back.

Series: Comparisons of True Courage

Creator: Utagawa Kuniyoshi

Period: Edo

Date: 1856

Culture: Japan

Medium: woodblock print; ink and color on paper

Repository: Tokyo National Museum

Now, instead of hair, Kiyohime angrily gnaws on a part of her kimono. With furrowed eyebrows, her loose hair flies up around her. Finally, Kiyohime has become enraged enough to complete her transformation into a dragon. This piece incorporates all the motifs previously mentioned: Kiyohime’s kimono is patterned with triangle scales and semicircle waves, and sakura blossoms fall from above the bonshō. This print takes a different approach to Kiyohime’s transformation in comparison to the first scroll painting. Rather than directly portraying her as a serpent, Kiyohime’s trailing kimono represents her dragon tail. Another hint at her transformation is her pointed, subtly beastlike ears. As her kimono curls around the bell, flames can already be seen licking from within, where Anchin hides. The sakura blossoms are most prevalent in this piece, making Kiyohime’s corrupted beauty its focus.

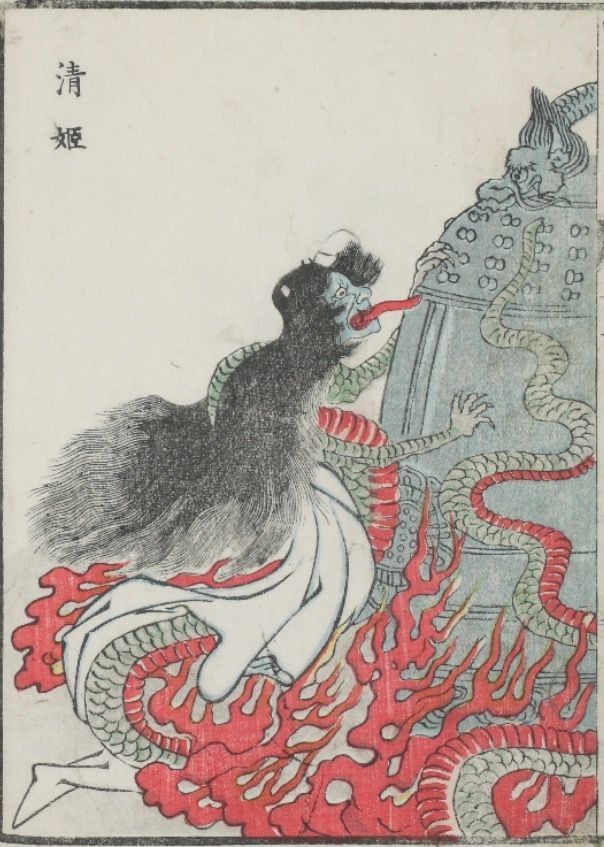

Source: Book of Yokai Pictures

Creator: Tamahide Nabeta

Era: Meiji

Culture: Japan

Medium: woodblock print; ink and color on paper

Dimensions: 36 x 26 cm

This print completes the tale of Kiyohime and Anchin. Kiyohime wraps her body around the temple bell, killing the cowering Anchin within. This bell is depicted with ornamental dragon heads, once again symbolizing Kiyohime’s transformation. This piece differs the most from all other pieces included in this collection. Kiyohime is not portrayed fully as a dragon (i.e. the Dōjō-Ji Engi Emaki) but does not fully maintain her human body (i.e. Kuniyoshi’s depiction). Instead, she is shown with a dragon’s body, but a woman’s head and hair. This depiction fully robs Kiyohime of the beauty she had when she was human. Instead, her monstrous appearance shows how her soul has lost all humanity.

Images:

Kunichika, Toyohara. “At the Edge of the Hidaka River.” Miwa Japanese Art, 1887, SKU Lot 00577, https://www.miwajapaneseart.com/product/at-the-edge-of-the-hidaka-river-toyohara-kunichika/.

Kuniyoshi, Utagawa. “Comparisons of True Courage: Kiyohime.” Jim Wageman Photo, SmugMug, 1856, Tokyo National Museum, Tokyo, Japan, https://www.jimwagemanphoto.com/Seasonal-Colors-of-Japan/A-Few-Days-at-Tokyo-and-Kamakura/A-Visit-to-the-Tokyo-National-Museum/i-WgbWQHz.

Nabeta, Tamahide. “Kiyohime.” Pinterest, https://pin.it/1bY4DIR.

Unknown, and Binabik. “Dōjō-Ji Engi Emaki.” Wikimedia Commons, 6 Apr. 2021, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/Category:Dojo-ji_engi_emaki.

Yoshitoshi, Tsukioka. “Kiyohime.” LACMA, 1865, Los Angeles County Museum of Art, Los Angeles, https://collections.lacma.org/node/191257.

Texts:

Shimazaki, Satoko. “Shades of Jealousy: The Body of the Female Ghost.” Edo Kabuki in Transition: From the Worlds of the Samurai to the Vengeful Female Ghost, Columbia University Press, 2016, pp. 150–93, http://www.jstor.org/stable/10.7312/shim17226.8.

Waters, Virginia Skord. “Sex, Lies, and the Illustrated Scroll: The Dōjōji Engi Emaki.” Monumenta Nipponica, vol. 52, no. 1, Sophia University, 1997, pp. 59–84, https://doi.org/10.2307/2385487.

Yasui, Manami. “Depictions and Modelings of the Body Seen in Japanese Folk Religion: Connections to Yokai Images.” Advances in Anthropology, vol. 07, no. 02, 2017, pp. 79–93. Scientific Research Publishing, https://doi.org/10.4236/aa.2017.72006.

Wow!! This history its so cool, tank u for this perfect post and them beautiful paintin.