The Heian Period was Japan’s “Golden Age”. A period where Japan began to shift away from Chinese influence and started to develop its own sense of national identity and classical style. The Heian period ranged from 794-1185, at this time the capital was moved to Heian-kyō (modern Kyoto), beginning a period of grandeur and elegance that started creating a unique Japanese culture through art, literature, architecture, and feudal classes. The presence of Nara sculptures stayed throughout this period, but the use of lacquered wood-core technique arose at this time. Lacquer was seen in both sculptures and architecture. The Landscape of today’s Kyoto was protected on three sides of mountains, this influenced the pilgrimage into the woods to build secluded temples for spiritual practices. The use of nature and landscape not only influenced the location sites of pagodas and temples but was a great component of many paintings.

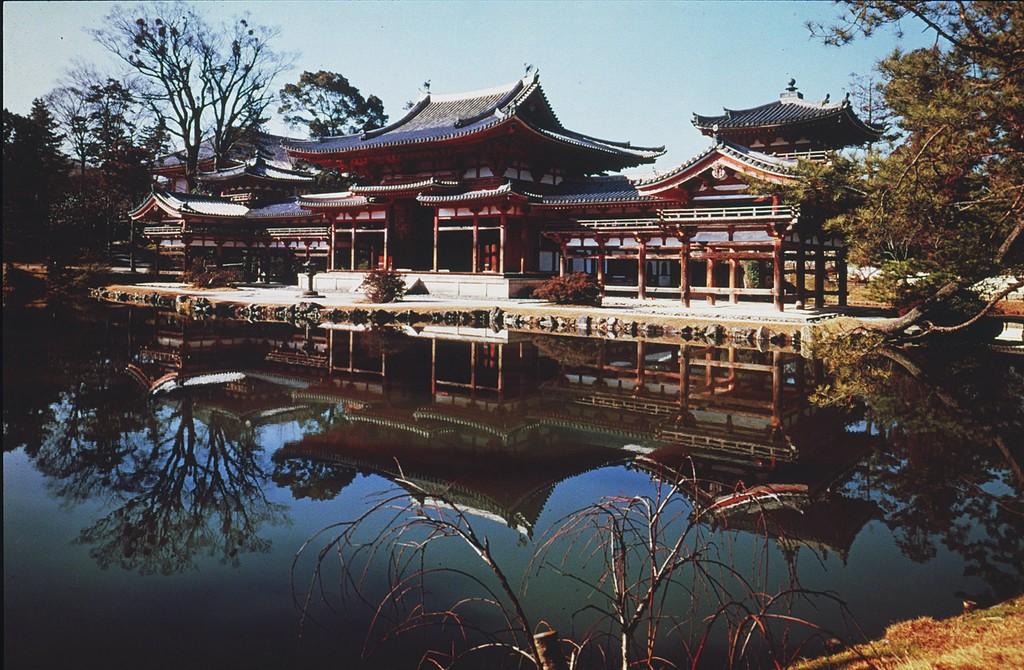

This spirituality was a movement of Buddhism that was greatly influenced by the Imperial Family, the Fujiwara. The influence of Fujiwara’s wealth and patronage shaped the way religious art was viewed. A notable structure at this time that was orchestrated by this family was the Phoenix Hall of the Byōdō-in (a Buddhist temple in Uji, outside Kyoto). The idea of “pure land” was an aspect of Buddhism that the Fujiwara took on to show the belief that Amida, (the Buddha of infinite light) could bring enlightenment through a ritualistic journey into the seclusion that was present at this time (Akiyama, 1993). This family also introduced a higher level of culture and literature through the aristocratic women of this period. A Heian court lady, Murasaki Shikibu, was an influential writer connected to the Fujiwara that helped shape the arts at this time (Cartwright, 2017).

The Yamato-e was the earliest account of this style during this period. Depictions of native scenes, history, and landscapes were all themes that were painted with this style. This was a huge turning point in Japanese art as this style created a sense of national identity as art diverged from Chinese influence. In addition to the sense of nationality forming, the start of the class system allowed powerful families and clans to assert the influence of the culture and government at this time (Hennessey, 2015) These different aspects came together and started to define “Japan-ness” as the departure from Chinese influence and the creation of a classical era that set the standards of art, architecture, and literature for generations to come; the Japanese national identity.

Japan’s “Golden Age”

Title: Five-story pagoda at the Muroji.

Size: Five stories

Located: City of Uda, Nara Prefecture, Japan

Date: Late 8th-early 9th century

Material: Wood, stone

Creators: Shingon Buddhist

Culture: Japan

Retrieved from:

https://library.artstor.org/asset/HUNT_55699

Source: Data From The John C. and Susan L. Huntington Archive of Buddhist and Related Art, The Ohio State University

This was a period of solace and pilgrimage. This Buddhist temple was sought as a religious retreat into the solitude of the mountains and forest. This religious temple was comprised of a low foundation stone, a wooden body with layers and curved edges, and a four-sided roof with a finial.

Size: H. 18 in. (45.7 cm); W. 8 3/8 in. (21.3 cm); D. 5 in. (12.7 cm)

Material: Wood; single-block (ichiboku-zukuri) construction, with traces of red and black pigment

Date: 11th-12th century

Location: The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Culture: Japan

Retrieved from : https://library.artstor.org/asset/SS7731421_7731421_11299071

Credit: The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Purchase, Friends of Asian Art Gifts, 2015 2015.5

This sculpture is a great example of the material and technique of the period. A single wood block has been carved and hollowed out, which is a common practice across multiple time period of Japanese art. The use of lacquer and elements of red and black pigment help indicate this piece was from the Heian period. The creation of the Shinto Deity was also a style of this time. They represent spirits that can take the form of important elements, wind, rain, mountains, etc.

Title: “Senzui Byobu (Landscape with Figures Screen).”

Size: Each 146.4 x 42.7 cm

Material: Six-fold screen, color on silk

Date: Late-Heian Period (11th Century)

Location: Kyoto National Museum,

Culture: Japan

Retrieved from: https://www.kyohaku.go.jp/jp/collection/assets/meihin/butsuga/item02d.jpg

The yamato-e paintings were done on scrolls, many with partitions. This painting has six distinct sections which work together to set the scene and tell a story. The style of this type of painting typically encompasses landscapes with Japanese features, alluding to Japanese poetry, history, folklore. This specific piece has many components from both Chinese and Japanese cultures. This yamato-e shows a hermit composing poetry in his hut as some noblemen are arriving to visit him. The hermit is Bai Juyi, a Chinese musician, poet, and politician during the Tang dynasty. The subject matter of this painting appears to be chinese but when looking closely you can see elements that are representative of the classical Japanese style beginning to develop at this time. There are blurry figures, mountains, water, trees and rocks indicative of the Japanese landscape paintings at this time. In addition the colors are cold and withered, which was a theme prevalent among the Japanese elite. This cold and withered color of soft greens, tans, browns along with the blurriness and mysticism is representative of the death of Chinese influence and a slow rebirth into a new culture. This painting shows great juxtaposition of old Chinese style and emergence of a new national style.

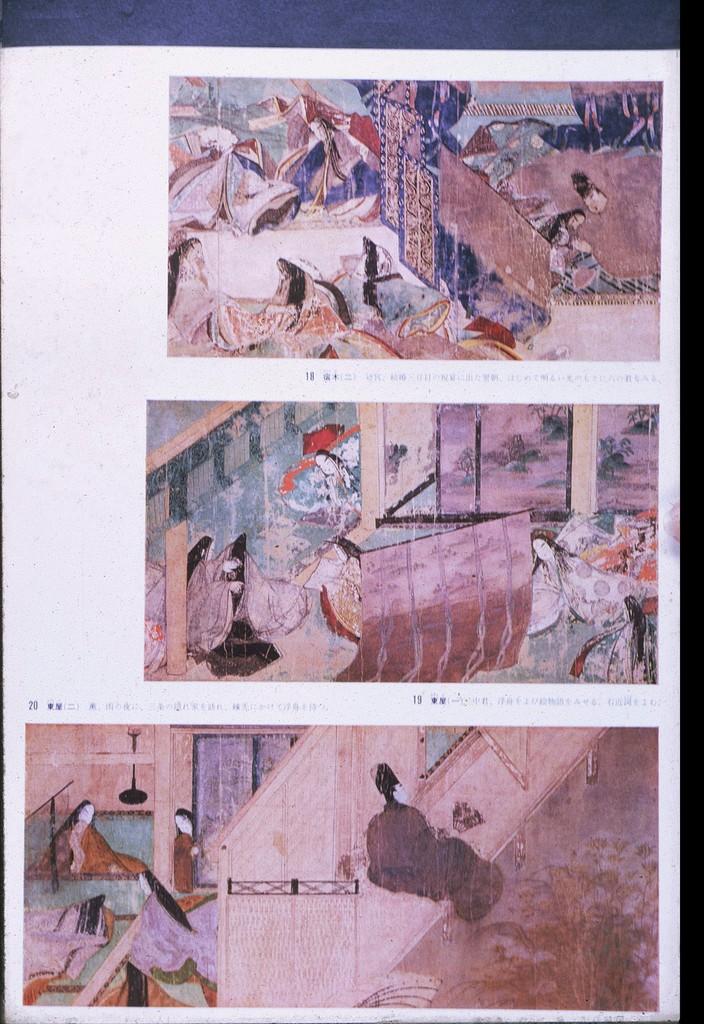

Title: Tales of Genji

Size: unknown, broken up sections of original scroll shown

Material: emakimono picture scrolls, drawn or stamped on long rolls of paper or silk

Date: 12th century

Location: Tokugawa Art Museum and the Gotoh Museum

Culture: Japan

Retrieved from : https://shibbolethsp.jstor.org/start?entityID=https%3A%2F%2Fidp.conncoll.edu%2Fentity&dest=https://www.jstor.org/stable/community.13602084&site=jstor

Credit: University of California, San Diego

This piece shows both the development of arts and literature during and after the Heian period. The Tales of Genji was the world’s first novel written by Murasaki Shikibu around the year 1000. The novel followed the romantic liaisons of the fictional Prince Genji, it was targeted for women of the court but served to be an inspiration for the Japanese national identity of the time. With a shift away from Chinese influence, this novel was written in “kana”, a new and developing syllabic Japanese. Shortly after this became the basis for a new Japanese calligraphy. This novel was later adapted into this piece by the ink painter Yūsetsu many different calligraphers (Kimi & Yoda, 1993).

This novel was adapted into an Emakimono painting, which is an illustrated horizontal narration system of painted scenes and narration through a calligraphic extract. This scroll was painted on long rolls of paper and silk containing over 50 chapters. Each section was richly decorated with gold and silver powder that was representative of the Japanese royal court of the period.

Each scene encompassed Yamato-style paintings. Throughout the Emakimono, Japanese life and landscapes were painted with an emphasis on rich colors and the decorative appearance of characters. In the middle section, a maid reads to entertain a noble women while another combs her hair. Strong diagonal elements cut through the painting to create an emotional intensity to the scene. The noble figure is stylized, demonstrating her class ranking which was an important part of the culture at this time. The emergence of both yamato-e and emaki paintings were maturations of pre existing techniques, brought together in a more distinctly Japanese was to emulate the period. This piece was a turning point in Japanese art and literature as they started to develop a new standard, or a golden standard for other influential Japanese artist, poets and novelists to follow in later time periods.

Size: Each height: 13.5 meters, the width (north and south): 47 depth( east and west):35 meters.。

Material: wood with marble staircase Source:Data from: University of California, San Diego

Date: from 1052 (Heian period)

Location: Kyoto (Japan)

Culture: Japan

Retrieved from: https://shibbolethsp.jstor.org/start?entityID=https%3A%2F%2Fidp.conncoll.edu%2Fentity&dest=https://www.jstor.org/stable/community.13920056&site=jstor

The structure of this building plays into both the naming and the deeper meaning of the Phoenix Hall. A main rectangular structure with two L-shaped wing corridors and a tail corridor is set at the edge of a large artificial pond. These components physically shaped a bird-like structure. Inside, there is an Amida sculpture made of Japanese cypress and covered with gold leaf. Yamato-e-style paintings line the walls inside this hall and create a space where both religious, aesthetic, and artistic aspects of this period all coexist in a shared space.

This architectural site ties all the previous images together. A Phoenix is a mythical creature that is capable of rebirth. This hall is symbolic of the “pure land”, the celestial realm of a Buddha where Buddhists aspire to be reborn. This death and rebirth is a major component of both Buddhism and the shift of Japanese culture at the time.

The influence of the Fujiwara Clan and Buddhism helped create a movement in Japan during the Heian period. As art, culture, and literature shifted away from classical Chinese influence, a new wave of culture was defined. A unique golden standard of Japanese culture was created, making this period known as “The Golden Period”. These standards helped create a national Japanese identity and created a strong sense of “Japan-ness” for future generations and time periods to follow.

Bibliography

Akiyama, T. (1993). The Door Paintings in the Phoenix Hall of the Byōdōin as Yamatoe. Artibus Asiae, 53(1/2), 144–167. https://doi.org/10.2307/3250512

Cartwright, M. (2017, May 9). Fujiwara clan. World History Encyclopedia. https://www.worldhistory.org/Fujiwara_Clan/

Hennessey, J. L. (2015). Discourses of the Heian Era and National Identity Formation in Contemporary Japan. (Working papers in contemporary Asian studies; No. 43). Centre for East and South-East Asian Studies, Lund University.

Kimi, Komashaku, and Tomiko Yoda. “A Feminist Reinterpretation of ‘The Tale of Genji’: Genji and Murasaki.” U.S.-Japan Women’s Journal. English Supplement, no. 5, 1993, pp. 28–51. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/42772059. Kimi, K., & Yoda, T. (1993). A Feminist Reinterpretation of “The Tale of Genji”: Genji and Murasaki. U.S.-Japan Women’s Journal. English Supplement, 5, 28–51. http://www.jstor.org/stable/42772059