The violence and destruction of World War II in Japan had a profound effect on the country for many decades following the conflict. These long lasting effects aid in contextualizing a preoccupation with physical damage, destruction, and obliteration in Japanese art and media. The atomic bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki by the United States in 1945 caused traumatic loss of life and effectively flattened the two cities. Seeing their homes, neighbors, and family members obliterated, wiped to nothing in mere hours, instilled in many Japanese artists a sense that everything one can know and become accustomed to will eventually return to nothing, destruction is inevitable and life itself is transient.

World War II also featured a considerable rise in facism in Japan and throughout the world. Many of these totalitarian governments held heavy restrictions on the production and exhibition of abstract art. The Nazi Party famously held the Degenerate Art Exhibition to deter people from creating art that did not align with their regime’s agenda.Similarly, the Japanese government banned all art exhibitions, except for those organized by the Great Japan Patriotic Art Association in 1944. Restrictions like this affected art movements in Japan in the following years, leading to anti-establishment art movements that celebrated abstraction and creativity in the decades immediately following the war.

Gutai

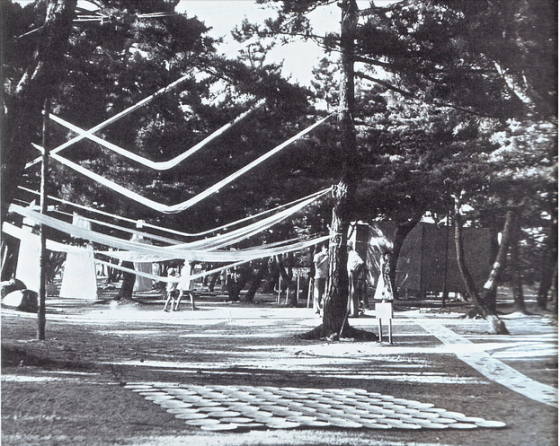

The Gutai Art Association was one such group, formed by 18 young artists in 1954 and led by Jiro Yoshihara. The movement emphasized a focus on play and creativity, an expression of the relief and liberation of the post-war environment. The group utilized a wide variety of mediums and created a lot of large scale, multimedia paintings and works intended to be interactive with the public. The Gutai group’s first public exhibition was held in a public pine forest in Ashiya, Japan in the summer of 1955, and they went on to hold many other outdoor exhibitions. Under the tutelage of Jiro Yoshihara, artists were instilled with the value of innovation and encouraged to seek out pure creativity in order to create work that was completely unique and unlike anything that had ever been seen before. He often encouraged students to create work on stages or in public parks to incite them to think outside of the existing frameworks of the art world.

In Motonaga Sadamasa’s Work(Water) from 1956, pictured here, hammock-like bags of colorful water stretched across the trees of a public forest like giant brushstrokes. This, along with many other pieces of art from the Gutai Movement, highlighted the use of public outdoor spaces in an effort to produce art that was joyful, creative, and accessible to the public.

This image shows artist Shozo Shimamoto throwing bottles of paint onto a canvas to create a work. His work exemplifies the blurring of lines between painting, performance, and sculpture within the Gutai Movement. Additionally, it demonstrates the same idea of chance seen earlier, with the artist forfeiting his control of the application of the paint, and letting the random breaking of the bottles create the details of his work instead. These actions of chance destruction are seen frequently in Gutai works like Saburo Murakami’s tearing of paper or Kazuo Shiraga swinging by a rope in order to paint with his feet. Using forces outside of the artist’s control helped them to produce art that was completely unique and one of a kind, as even the artist themself could not replicate it exactly.

Mono-ha

Another concurrent Japanese modern art movement I want to highlight is the Mono-Ha movement. Mono-ha roughly translates to the school of things in English, emphasizing the movement’s focus on the arrangement of objects, or things, in order to highlight their relationship with one another and the space around them and create what they called an encounter with being. Sekine Nobuo’s 1968 sculpture Phase– Mother Earth is often considered to be one of the defining works of the Mono-ha movement. The artist dug a cylindrical hole in the ground and used the excavated dirt to create a cylinder on the ground next to it with identical dimensions, with the goal of instilling the viewer with a greater understanding of their connection to the space around them. Unlike the Gutai Association, Mono-ha artists avoided using any symbolism or representative motifs in their art, and aimed to arrange things, rather than create them. They also expressed a specific interest in creating a new sense of modern Asian identity in their art, without conforming to the traditional conventions of either Western or Japanese fine art. Many Mono-ha artists studied Buddhist philosophies to inform the conceptual idea of their art, although their goal was not to use any of these ideas as a source of visual representation. Buddhist ideas informed Mono-ha ideas like the concept that space is fundamentally void, and the idea that there is no separation between the object, the viewer, and nature. Through the careful juxtaposition of natural materials Gutai artists aimed to highlight the interdependent relationship between the things that they used in their art and the space around them. Some Mono-ha artists also created work that was deliberately meant to deteriorate or be destroyed, which can be seen as a reflection of the Japanese fixation on deterioration and destruction, following World War II. Artists like Kashukio Narita and Endo Toshikatsu created sculptures by burning wood, which allowed them to demonstrate the transient nature of their natural materials and remove themselves from the act of making, leaving the creative process up to nature instead.

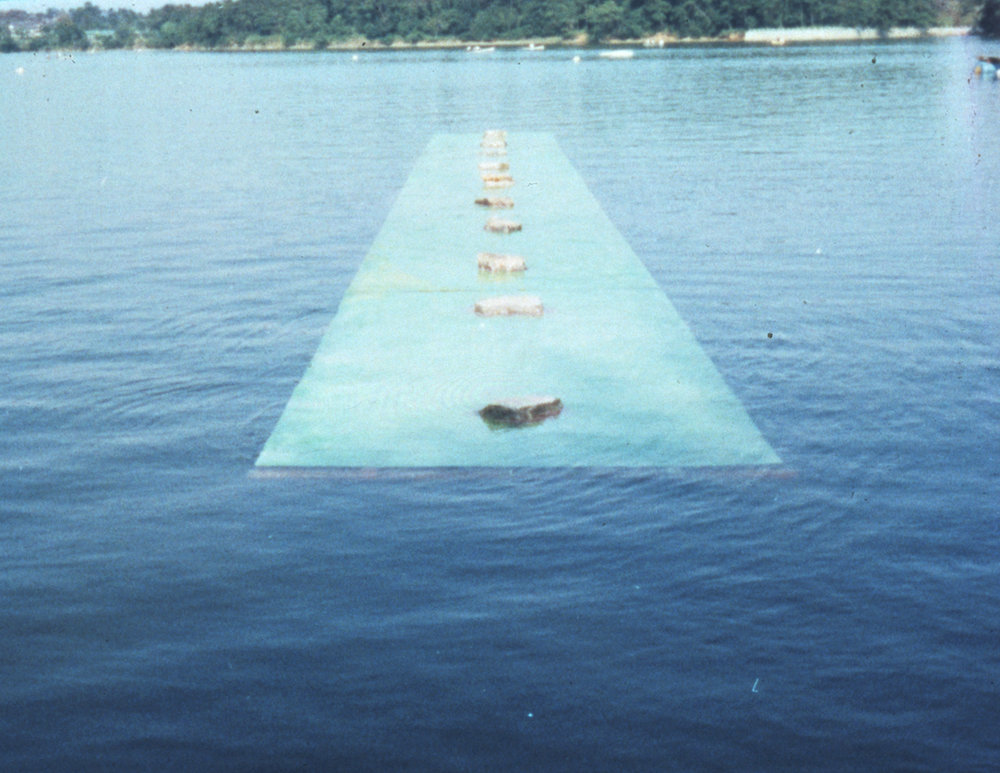

This image shows Kishio Suga’s Law of Situation (1971), which features stones resting on a plastic board, floating in a much larger body of water. Suga was known for using the situation of objects to examine the forces surrounding them, in this case the weight and density of the rocks is juxtaposed with their position floating at the surface of the body of water. The ripples of shallow water surrounding the rocks suggests the carefully raked gravel of traditional zen rock gardens.

Lee Ulfan’s Relatum (1968), pictured here, features a large rectangular stone resting on a sheet of glass, which has been broken by the act of placing the stone onto it. The artist is playing with chance and allowing natural forces to determine the final outcome of his art.

Obsessional Artists

The last group I am highlighting are the so-called “Obsessional Artists” of the 1960s, which included three Internationally known Japanese artists, Kusama Yayoi, Miki Tomio, and Kudo Tetsumi. These artists had some affiliations with other movements but largely worked independently, focusing on creating art out of the necessity to heal and using concentration and obsessive motifs as a means of survival. Artists like Kusama and Miki used repetition to create rituals that were healing to themselves within their artistic practices. Kusama utilized repetitive imagery like polka dots and ‘infinity nets’ across sculptures and entire rooms to obfuscate the forms in front of her. Her goal was ‘self obliteration’- by creating a sense of infinite space and repetition, she could reduce herself to nothingness. Miki was similarly repetitive in his work, choosing to depict the same subject matter, his ear, for the entirety of his career. When reflecting on this decision, Miki expressed that he is not drawn to the ear as an object or symbol, and is instead drawn to the act of repetition. With Kudo, there is not the same clear obsessive repetition within each of his pieces, but his work shows a similar preoccupation with the human body to Kusama and Miki. He consistently uses imagery of grotesque, rotten-looking body parts, and imagery of plants and earth. Together this creates a narrative of the fragile, transient nature of life, as well as an understanding of the potential for growth out of the decay of life and society as it is known today.

Kusama Yayoi’s Phalli’s Field, 1965

Miki Tomio’s Ear Unit 106, aluminum, 1965

Kudo Tetsumi’s Bonheur, mixed media, 1974

So, in an increasingly globalized world, what makes modern artists in Japan japanese? What makes Gutai paintings different from American action painting, Mono-ha different from minimalism? World War II created shared experience and trauma within Japan and directed the nation’s attention to themes of destruction and obliteration, but a lot of themes like chance and transience have existed with Japanese art and philosophy long before the war. Much like the creative practices of artists like Kusama Yayoi and Miki Tomio, many Japanese Buddhist practices are deeply ritualistic, like the careful routine of traditional tea ceremonies. The Buddhist teaching of one-ness can be seen in many modern art practices as well, reflected in the ideas of blurring the lines between man, nature, and object seen in Kudo Tetsumi’s work and in the ideology of the Mono-ha movement.

Bibliography

Chiba, Shigeo. 1984. “Modern Art from a Japanese Viewpoint.” Artforum, October 1984. https://www.artforum.com/features/modern-art-from-a-japanese-viewpoint-207659/.

Estes, Clary. 2017. “Obliteration through Obsession.” Medium. September 11, 2017. https://medium.com/@claryestesphoto/obliteration-through-obsession-ca63f689da90.

“GUTAI.” n.d. Whitestone Gallery. https://www.whitestone-gallery.com/pages/gutai.

“Japanese Modernism across Media | Outdoor Exhibition Practices · the Gutai Group: Engaging in Experimental Methods.” n.d. Ds-Omeka.haverford.edu. https://ds-omeka.haverford.edu/japanesemodernism/exhibits/show/gutaigroup/outdoor-exhibition-practices.

Munroe, Alexandra. 1994. Japanese Art after 1945. Harry N. Abrams, Inc.

Rawlings, Ashley. 2009. “An Introduction to ‘Mono-Ha.’” Tokyo Art Beat. November 26, 2009. https://www.tokyoartbeat.com/en/articles/-/an-introduction-to-mono-ha.