Stones are essential building materials and have been widely used. Stones are static and abiotic objects; however, humans can view them from a dynamic perspective. From a static perspective, Stones have two categories: raw stones and stone products. Raw stones are unique and present the beauty of Wabi-sabi, a sense of history, etc. For example, the raw stone in Rikugi-en Garden represents a mountain or island where gods live. The stone products have a beautiful and special design and are handmade, such as Japanese Toro(lantern). From a dynamic point of view, stones narrate philosophical stories; for instance,15 stones in the Ryoan-ji are representative of the impermanence and imperfection of Wabi-sabi. Thus, stones are both aesthetic and ideological. Examples in the exhibition are from 768 to 1700. All samples are connected to Buddhism and Zen; More importantly, they all include stones as crucial elements.

Title: Toro and Deer

Creator: Aoye Yuan

Date: 2017

Location: Kasuga-taisha

Culture: Buddhism

Description: Stones can be a masterpiece of art in Japanese gardens. Besides the practical uses of Stones, stones have artistic value too. Stone Toro (lantern) is widely used in Japanese gardens, and it is well designed, having a beautiful shape and delicate sculptures. Stones are solid and long-lasting, representing immortality. The stone Toro was originally used in Buddhism to represent the infinite and endless wisdom and power of Buddha. Houju(crown gem), Ukebana((lotus-shaped support of a seat), and Kasa(umbrella) of Toro have a similar structure with the top of the pagoda. Additionally, light means hope and justice in Buddhism, and Toro represents a guide who helps people out of darkness. It is said that during the Momoyama era, Rikyū, who was a master of tea ceremony, saw the beauty of Toro in the mist at sunrise and brought it to the Japanese garden. Stone Toro combines the symbolic meanings and beauty, having an irreplaceable position in the Japanese garden.

Title: Rikugi-en Garden

Creator: Berlin, Kimon

Date: 2017

Location: Rikugi-en Garden

Culture: Japan

Title: Daisen-in stone garden

Creator: Ivanoff Commonswiki

Date: 2004

Location: Daisen-in stone garden

Culture: Japan

Description: In the pond gardens, raw stones are from nature, showing a sense of age and the beauty of imperfection of Wabi-sabi. Both Shinto and Buddhism deem that gods live on spiritual mountains, and the peaks of those mountains are sacred. Most shrines are built on hills or islands. Stones in the pond garden have more symbolic meanings of those holy places. The stones at the center of a pond in the Rikugi-en Garden represent an ocean island, just like a piece of naturally formed rock in Darwin’s Arch. When audiences walk around the pond, they approach a God-like perspective; they can overlook both “ocean” and “islands.” In addition, raw stones are reminiscent of other creatures or things. The stone garden, constructed by only stones and plants, was first built in the Kamakura period and was famous in the Muromachi era. During the Kamakura era, the stone gardens are of concretization, and stones represent a substance. In Daisen-in, a stone pretends a boat, and the leveled gravels act as water’s wave created by a boat. The Daisen-in is representative of the early-stage stone gardens. Thus, stones in Japanese gardens have both aesthetic and emblematic functions.

Title: Ryoan-Ji

Creator: Cquest

Date: 2007

Location: Ryoan-Ji

Culture: Japan

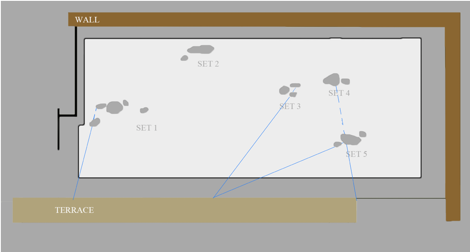

Title: Stones’ position at Ryoan-ji

Creator: Aoye Yuan

Date: 2021

Culture: Japan

Description: : After the Muromachi era, stones indicate Zen and Buddhism. The stone gardens express an owner or designer’s ideology. The Ryoan-ji has 15 large and small stones on the gravels. Statically, the basic interpretation of Ryoan-ji stone garden is 15 islands on the ocean or 15 peaks of mountains among the mist based on their construction. It’s beautiful and imaginative to view the garden as a picture. However, if looking at it dynamically, viewers will discover more metaphors and philosophy in the garden. Among 15 stones, only the utmost 14 stones can be seen no matter where the audiences stand, which is representative of Wabi-sabi. Wabi-sabi originated from the three marks of existence of Buddhism that includes imperfection, asymmetry, roughness, simplicity, austerity, etc. In Zen Buddhism, human desires are infinite and cannot be fulfilled, just like that you cannot see all stones from any point. Moreover, Buddhism suggests that people should give up their wants.

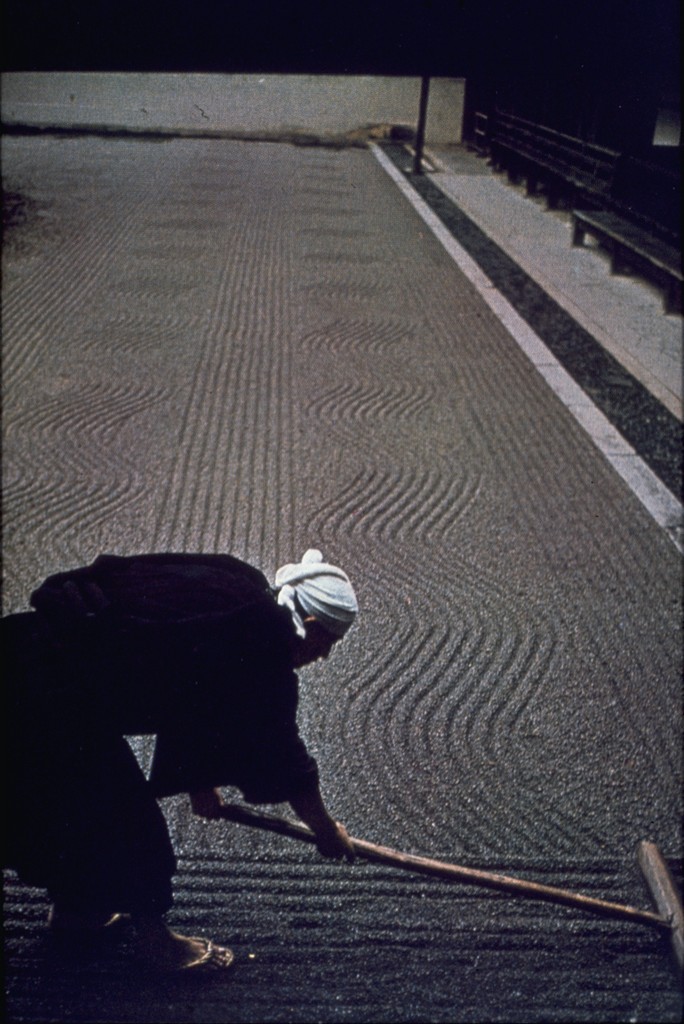

Title: Monk raking gravel into decorative patterns in a Zen dry garden

Creator: unknown

Date: unknown

Culture: Zen/Buddhism

Description: The maintenance of the stone garden is a crucial part of the stone garden’s philosophy; stones present Japanese people’s world view in the procedure of raking. Raking is leveling the stones, keeping the garden clean and tidy. In Zen and Buddhism, destiny and fate are essential ideas. Stones have destinies. All stones, including mountains, architecture, and sculptures, will be crushed by rain, stream, sand, wind, etc. until they turn to dust. During raking, stones are devastated by the rake and finish their lives by turning to dust. The Stone Garden means presenting the fate of everything. Childhood of humans is like when new stones are added to the garden, fresh and various differently. People face all kinds of difficulties after birth, just like stones are being raked. Stones will be more similar to each other, and more things restrict adults. Finally, stones vanish to dust, and humans die.

Bibliography

Anika. “Stone Lanterns in the Japanese Garden.” Real Japanese Gardens, last modified January 20, 2021. https://realjapanesegardens.wordpress.com/2021/01/20/stone-lanterns-in-the-japanese-garden/.

Berlin Kimon. IMG_6729. Photograph. Flickr. November 29, 2008. https://www.flickr.com/photos/kimon/3268682188/.

Commonswiki, Ivanoff. Daisen-in1. Photograph. Wikimedia Commons. September 7, 2004. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Daisen-in1.jpg.

Cquest. Kyoto-Ryoan-Ji. Photograph. Wikimedia Commons. May 2007. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Kyoto-Ryoan-Ji_MG_4512.jpg.

Madej, Ken. “Zen, Stones and a Dialogue with Masuno Shunmyo.” Landscape Australia 27, no. 1 (105) (2005): 54–55. http://www.jstor.org/stable/45165680.

Masaki, Horiuchi. 图解日本园林 (Japanese Garden). Translated by Min Zhang. Nanjing: Jiangsu fenghuang kexue chubanshe, 2018.

Nitschke, Günter. Japanese Gardens: Right Angle and Natural Form. Italy: Taschen, 2003.

Nonaka, Natsumi. “The Japanese Garden: The Art of Setting Stones.” SiteLINES: A Journal of Place 4, no. 1 (2008): 5–8. http://www.jstor.org/stable/24889320.

Obv. Darwinarch. Photograph. Wikimedia Commons. November 14, 2008. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Darwinarch.jpg.

Optional, Username. “ASMR Japanese Zen garden 禅の庭.” Aug 7, 2013. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=kff7GsbagQo.

Ramberg, Dodd, Walter. “Some Aspect of Japanese Architecture.” Perspecta, 1960, Vol. 6 (1960): 34-47. https://www.jstor.org/stable/1566890.

Walford, Ros. “A Rough Guide to: the Japanese tea ceremony.” Rough Guides, last modified May 16, 2019. https://www.roughguides.com/article/a-rough-guide-to-the-japanese-tea-ceremony/.

Weiss, Allen S. “The Limits of Metaphor: Ideology and Representation in the Zen Garden.” Social Analysis: The International Journal of Social and Cultural Practice 54, no. 2 (2010): 116-29. http://www.jstor.org/stable/23182478.

Monk raking gravel into decorative patterns in a Zen dry garden. Photograph. Artstor. https://library.artstor.org/#/asset/AIC_780011.

“桂離宫略囡.” Imperial Household Agency. https://sankan.kunaicho.go.jp/guide/institution_katsura.html.