In recent years, I have developed a heightened awareness and appreciation for Vietnamese culture and traditions. Although I grew up in Vietnam, my education regarding the cultural significance of my surroundings was limited. This is partly due to the inherent difficulties associated with studying Vietnamese culture. In comparison to countries within the Sinosphere cultural group, such as China, Korea, and Japan, Vietnam possesses fewer historical records and artifacts. The tumultuous history of war and colonization has resulted in the destruction or loss of many significant historical items. Furthermore, Vietnam’s tropical climate poses difficulties in preserving artifacts due to the high humidity. It is also worth noting that Vietnamese culture has undergone diverse influences, including Chinese culture and French colonialism (Denecke and Nguyen, 2019). This fusion of influences further complicates the study of Vietnamese culture, particularly when compared to Sinosphere cultures with fewer external influences.

Throughout my K-12 education, my exposure to the arts was primarily limited to the period during and after the Indochina Wars. However, in recent years, there has been a surge among local scholars and younger generations to study the culture during the Revival Le (1533-1789), Tay Son (1778-1802), and Nguyen dynasties (1802-1945) – the final Vietnamese monarchies – as ample resources and records from these eras still remain. Working on this paper for Intro to Asian Arts, I recognized the tremendous opportunity for me to educate myself on the topic, specifically the arts and culture during the Nguyen dynasty. This period is particularly intriguing due to the coexistence of the French occupation of the country and the Vietnamese monarchy (Wikipedia Contributors 2022). When considering the thousand-year influence of China, the years from 1930 to 1945 unveil the manifestations of the blend of French, Vietnamese, and Chinese cultures.

Backgrounds

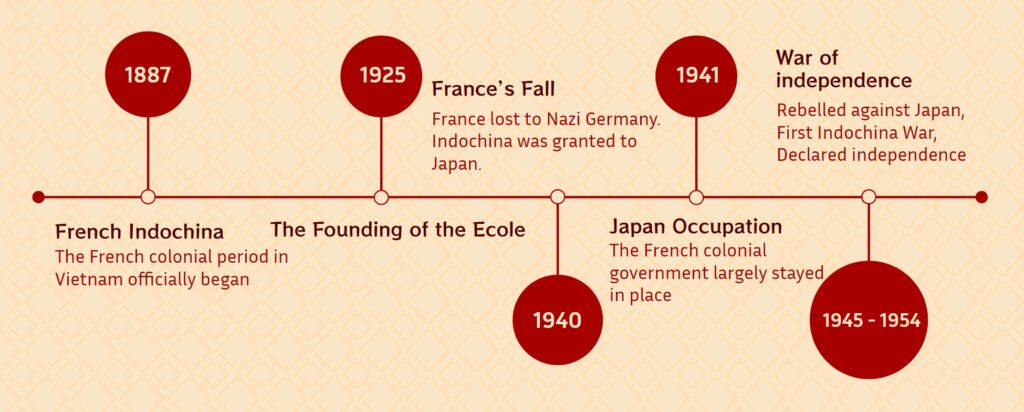

Now, why did I select the period 1930-1945 instead of 1887-1945, considering that 1887 marked the official colonization of Vietnam by the French and the renaming of the country as French Indochina (Llewellyn, Southey, and Thompson 2018; Wikipedia Contributors 2022; Zhao 2022)? While it is true that the French officially governed Vietnam from 1887, the artistic landscape only experienced a significant transformation starting in 1925 with the establishment of the École des Beaux-Arts de l’Indochine (EBAI), commonly referred to as the Ecole (Taylor 1997). The EBAI was a School of Fine Arts founded by two French painters Victor Tadieu (1870–1937) and Joseph Inguimberty (1896–1971), along with Nguyen Van Tho (1890–1973, better known as Nam Son), who was sent to Paris for a year of training in 1924 for his new post as an art instructor. The school was modeled after the École des Beaux-Arts in Paris, with the objective of merging Western art with Far Eastern traditions. Thus, while the curriculum included courses in life drawing, linear perspective, open-air painting, and oil painting, which were novel for Vietnamese students and distinct from their own artistic traditions, the school also fostered the study of local craft materials to elevate modern silk paintings and lacquer paintings. By combining Western art with local values, the French can promote their culture and values in Vietnam. Moreover, prior to the mid-20th century, few Vietnamese individuals ventured beyond their birthplaces, and French colonial rule restricted overseas travel for their subjects, leading to the majority of artists being educated at the Ecole during that era (Proctor, 2016). I chose to commence my research at the year 1930 because it marks the graduation of the first generation of students from the EBAI, and I concluded it at the year 1945 due to the outbreak of wars, which gave rise to another art style in Vietnam.

My specific focus for this chapter is lacquer painting, as it presents a captivating medium for artistic expression. Lacquer has been employed for thousands of years in Asia as a protective or decorative material for wooden objects and structures (ASIANA Fine Asian Art, n.d.; Bang, n.d; Safford, 2015; Wikipedia Contributors, 2021). However, working with lacquer poses challenges as it is toxic and requires a humid environment to dry, which may not initially appear appealing to artists. Additionally, traditional lacquer techniques were limited to five colors: brown, black, red, yellow, and white (ASIANA Fine Asian Art, n.d.). These limitations compelled painters to think innovatively in order to convey their ideas. Notable innovations include the inlaying of egg, crab, and snail shells, experimentation with dye mixing, and exploring different approaches to drawing shapes and figures, shading, and lighting techniques, as well as the application of pumice and polishing.

For this chapter, I have selected five lacquer paintings created by some of the most prolific alumni of the EBAI. The first three paintings are currently on display at the Vietnam National Fine Arts Museum in Hanoi, Vietnam, while the last two were either gifted or sold to French collectors. By analyzing these five examples, it is possible to observe how artists skillfully blend traditional values with Western art techniques, as well as discern the distinct characteristics of artworks intended for Western audiences versus those intended for Vietnamese audiences.

Women in a Garden (1939)

The first work is Nguyen Gia Tri’s standing screen Women in a Garden (Figure 2, 3).

Figure 3: Details of Women in the Garden. By Nguyen Gia Tri (1908-1993). Eight-fold screen; lacquer and egg shells on panels; h. 5’2” (160 cm), w. 13’ (400 cm). Vietnam. 1939. Hanoi, Vietnam National Fine Arts Museum. Photo by Vietnam National Fine Arts Museum.

This magnificent eight-fold standing screen portrays seven female figures of varying ages amidst lush tropical foliage against a backdrop of golden hues. On the rightmost side, two young girls can be seen playfully engaging in a game, dressed in flowing traditional ao dai garments. Adjacent to them, a middle-aged woman adorned in a resplendent golden ao dai sits serenely on a branch of cotton roses, her hair elegantly tied up, with a contemplative expression on her face. Positioned at the center is an esteemed elderly woman of the elite class, indulging in tea while resting her arm on a crimson cushion. On the leftmost side, a trio of young women joyfully stride forward, their arms interlinked. These three individuals don the more contemporary Lemur ao dai, influenced by French aesthetics, characterized by a sleeker fit and adorned with modern motifs (Duc and Bao, 2012). Notably, the woman in the middle of the trio wears a floral crown and carries a bouquet of flowers, exemplifying the assimilation of Western, particularly French, culture in Vietnam. To accentuate the presence of these female figures against the vibrant backdrop, the artist envelops them with a black aura. Technique-wise, we can see the unique feature in the works of Nguyen Gia Tri and his followers is a pseudo-craquelure, which is achieved by filling shapes with fragments of duck-egg shells rather than powdered ones, resulting in areas of white coloration that can also be delicately tinted (Safford 2015). The human figures are rendered with proportional accuracy, and the painter skillfully incorporates shading. This was likely influenced by Western artistic techniques, which tend to emphasize realistic portrayals of subjects (Fullen 2011).

This standing screen was originally found in Emperor Bao Dai’s Palace in Dalat before being transferred to the Vietnam National Fine Arts Museum in 1978 (Vietnam National Fine Arts Museum 2021). Therefore, this screen should be more appealing to the emperor, who is Vietnamese, than to Western audiences. As there are no existing records of similar depictions of women in a garden prior to the French occupation, Safford postulates that the subject matter of this painting was inspired by the art of mid-nineteenth-century French realists, late-century impressionists, and post-impressionists. Potential sources of inspiration could include Claude Monet’s Women in the Garden (1866) and Springtime (1872).

Fishing under the Moonlight (1943)

The second painting is Fishing under the Moonlight by Nguyen Khang (Figure 4).

This artwork depicts a semi-realistic scene of Vietnamese fishermen and women engaging in nighttime fishing activities. Two men can be seen rowing the boat, while the man at the front fishes with a net, and two women catch fish, snails, and crabs using their hands. In contrast to Women in the Garden, the background of this painting is dark, while the figures themselves are illuminated. In particular, the black lacquer delineates the night sky and dark water. The night sky and dark water are depicted using black lacquer, while the light-colored areas (yellow hues) are created through mother-of-pearl inlays that have a color-shifting effect depending on the viewing environment’s lighting conditions. The clever use of these inlays naturally draws attention to the figures, eliminating the need for a contrasting color background. The realism of the painting is achieved through the use of shading on objects, the intricate depiction of fabric movement and the fishnet, and the creation of an illusion of three-dimensional space on a two-dimensional canvas. These characteristics reflect Western artistic influences, attributable to the technical education received at the École des Beaux-Arts de l’Indochine.

On the other hand, we can also observe elements of Vietnamese artistic representation in the unrealistic aspects of this painting. Nguyen Khang’s simplistic figural style and the depiction of subaltern subject matter exhibit a more primitive quality reminiscent of pre-colonial folk art styles, such as woodblock prints from the Dong Ho craft village and water puppetry. For instance, we can notice similarities in composition between this painting and the renowned woodblock print Wedding of Rats (Figure 5). Both artworks are divided into two halves, with the women occupying a similar position to the groom rat on horseback, the fishes corresponding to the location of the palanquin, and the boat being positioned at the same place as the four rats at the top. Furthermore, the unrealistic elements in this painting stem from the unnatural and folk-like head poses, which resemble those found in the poses of the rats in the woodblock print.

Another folk art form that influences this painting is water puppetry. For example, the human figures in Fishing under the Moonlight are depicted wearing undergarments with a color scheme of red, black, and yellow, which closely aligns with the outfits of certain water puppets (Figure 6). Lastly, Nguyen Khang deliberately chose to portray one of the four common rural occupations (fisherman, woodcutter, plowman, and herdsman) that are frequently seen in puppetry performances (Safford, 2015).

Procession to the Pagoda (1935)

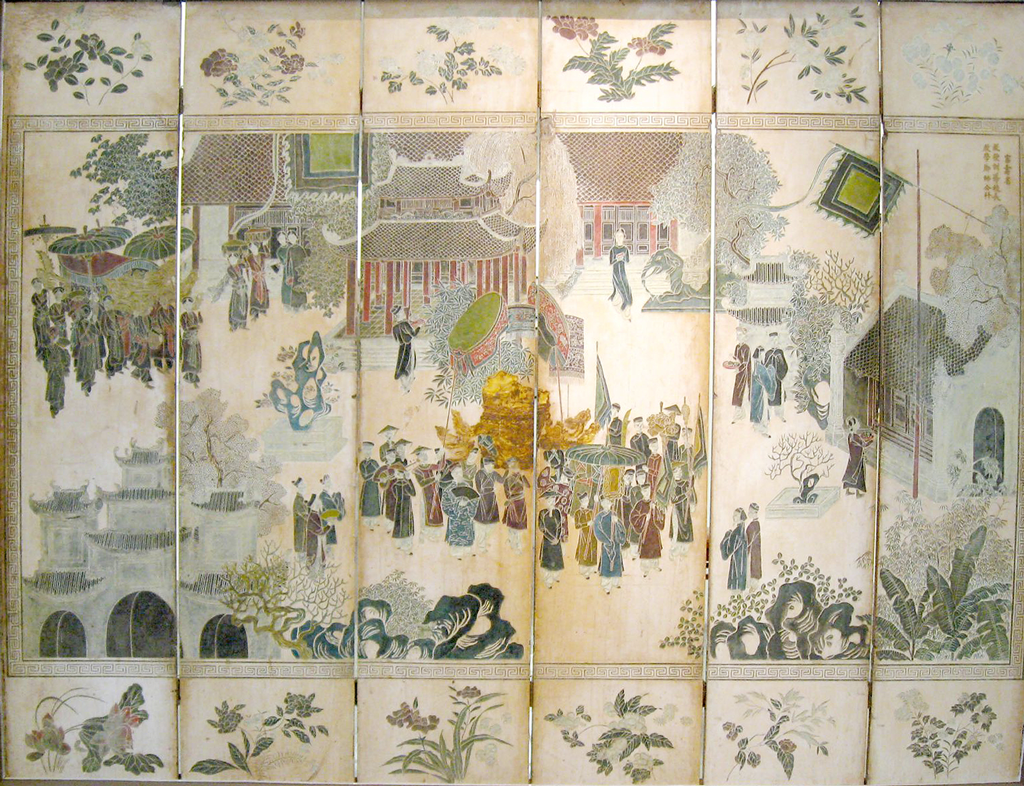

The third lacquer art piece is Procession to the Pagoda by Nguyen Van Bai (Figure 7).

This standing screen depicts a religious ceremony taking place in a Vietnamese pagoda. The pagoda features some iconic items in an Asian garden: four-sided curved roofs, single-floored pagodas, various types of local plants (bamboo, banana, etc.), and artificial rock mountains. At the top, two five-color flags, which hold great significance in Vietnamese festivals and religious ceremonies (Nguyen, 2022), can be seen. The five-color flag with squares surrounding it is the oldest recorded traditional flag in Vietnam, with each color representing one of the Eastern Law’s Five Elements: green (wood), red (fire), yellow (earth), white (metal), and purple (water). Additionally, the human figures depicted in the artwork are dressed in pre-colonial ao dai attire. Collectively, this painting captures the distinctive Asian characteristics of 19th-20th century Vietnam.

This artwork is intriguing because, despite the attempt to depict a three-dimensional effect on a two-dimensional surface and the attention to detail in portraying the subjects, there is no French influence apparent in the illustration or painting technique. Unlike previous artists, Nguyen Van Bai did not employ techniques to achieve a three-dimensional appearance, such as shading or highlighting, resulting in a primarily two-dimensional representation with unrealistic proportions, which is another trait of folk arts such as Dong Ho woodblock prints.

What makes this artwork even more interesting is Nguyen Van Bai’s adoption of the lacquer etching technique, which can be traced back to the carved lacquer process of the Song era in China (Safford, 2015). The technique involves coating a wooden surface with a thick layer of white chalk, followed by the application of layers of lacquer. The artist then carves into the surface with a sharp tool, filling the grooves with colors before sealing them with clear layers of lacquer. This process creates a sharper and crisper look compared to the traditional lacquer painting process, which typically involves building up layers of paint or lacquer and then shaving them off to achieve the desired effect (Insider Business, 2021; National Gallery Singapore, 2020).

The absence of French influence in this artwork is noteworthy, as it provides evidence that there were artists who sought to preserve and document Asian and Vietnamese culture during a period when French culture was widely adopted and represented in Vietnam. The Procession to the Pagoda screen stands as a testament to these artists’ dedication to capturing and safeguarding their cultural heritage.

Les èternitès (Eternities) (Circa 1935)

The first artwork that exemplifies the stark contrast between paintings intended for the domestic audience and those created for Western viewers is Les èternitès (Eternities) by Le Pho (Figure 8).

This five-fold screen, as noted in Christie’s entry, is a rare lacquer work by Le Pho, as he had an allergy to the material. It portrays a woman dressed in a white ao dai standing on a mountain, accompanied by a deer, and gazing at the sunset. The vegetation in the foreground serves as a focal point, inviting the viewer to explore beyond. In the background, mountains are depicted in two colors: black and orange. The elaborate use of orange and yellow hues emphasizes that the scene takes place during sunset. The transparent, sinuous clouds and the subdued color palette create a mysterious yet serene and dreamlike atmosphere.

This standing screen was a wedding gift from the artist to a French couple in Paris (Christie’s 2010) and we can see that it exudes Western values. This artwork can be described as semi-abstract, with an abstract background and a more detailed foreground. However, in comparison to the three previous pieces, this scene appears more realistic. The proportions are accurate, the shading is subtle, and the poses appear natural. Furthermore, the artwork exudes a sense of individuality, with a solitary human figure standing prominently at the center. Considering what we know about Chinoiserie arts, this piece would have appealed to Westerners at the time not only because it incorporates various Western artistic techniques and values but also due to its dreamy and mythical ambiance.

Upon closer examination, we discover that the representation of Vietnamese culture in this artwork is not as overt as in the previous pieces. Specifically, if we remove the ao dai from the composition, it becomes less evident to determine the artwork’s origin. So, what is the Vietnamese representation here? The painting is said to evoke the poetic words of one of the most prolific poets in 19th-century Vietnam, Mrs. de Thanh-Quan (Christie’s, 2010):

The shadow of dusk stretches across the immense sky

In the distance, the sound of a conch replies to the call of a drum.

These poetic verses suggest that the artwork seeks to capture the ethereal beauty of nature and evoke a sense of tranquility and contemplation. While the Vietnamese cultural elements may not be as explicit, the artwork aligns with the sentiments expressed in Vietnamese poetry, further adding to its cultural resonance.

Nine Carps in the Water (1939-1940)

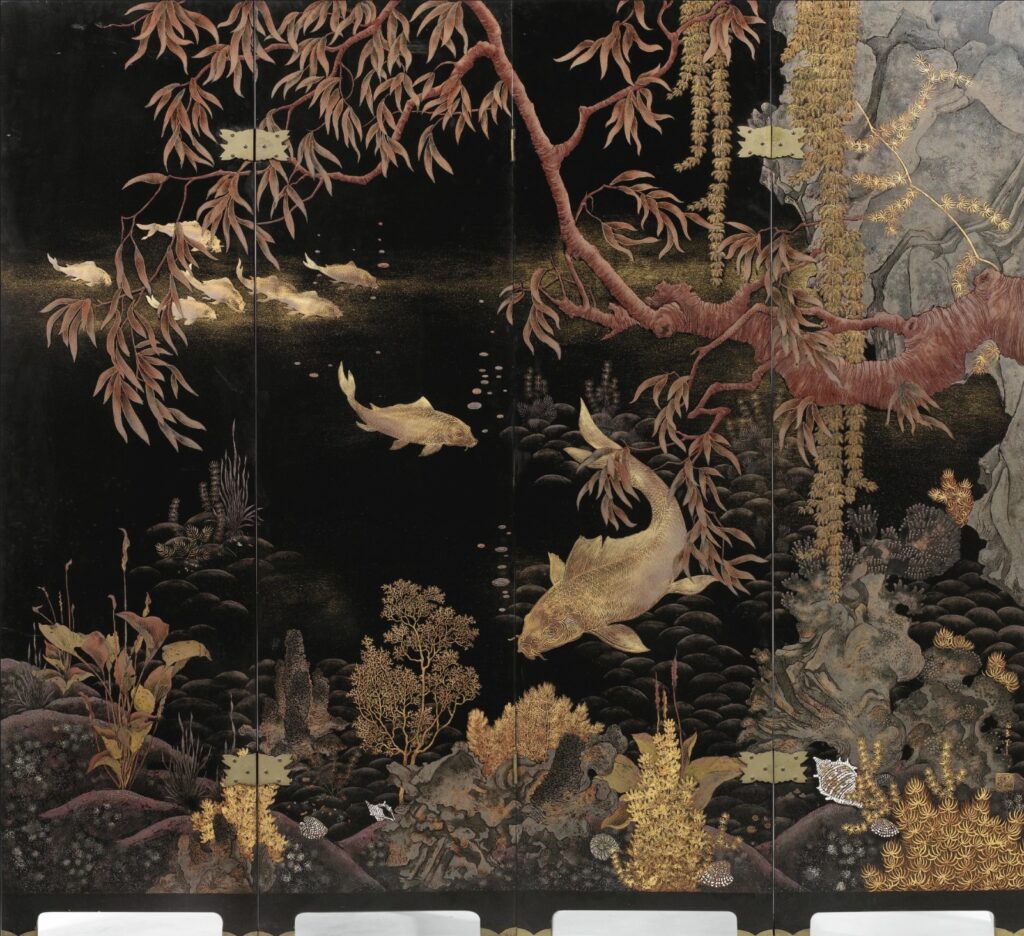

Another piece that shows the contrast between artworks staying in the country and those that are made for Westerners is Nine Carps in the Water (Figure 9) by Pham Hau.

This screen portrays a realistic scene of nine carp swimming in water. The bottom of the composition features small water plants, conch shells, and corals. On the right side, a portion of an artificial mountain is visible, while a willow tree grows from the right, spanning towards the left, framing the scene, and guiding the viewer’s gaze from the nearest carp to the ones further behind. The carps’ swimming path and their sinuous bodies create an elegant S-curve, imbuing the scene with a sense of fluidity, much like the ethereal clouds in the previous artwork. Similar to Fishing under the Moonlight, this piece employs a black background to represent water and utilizes mother-of-pearl inlay to draw attention to specific elements. The overall color scheme of the screen is dark and subdued. Yet, through the incorporation of the S-curve and other artistic choices, the composition exudes a mysterious, ethereal, and dreamlike quality.

Similar to Eternities, this artwork demonstrates proportional accuracy, skillful shading, highlights, and natural poses. However, instead of creating an abstract scene, this screen meticulously captures the minute details of each object, resulting in a highly realistic depiction.

Currently held in a private collection in France, there is no doubt that this screen would also captivate Western audiences, as it aligns with their preconceived notion of the Far East as an exotic, enigmatic, and otherworldly place. However, as with Eternities, a deeper understanding of Vietnamese or Chinese culture is necessary to fully appreciate the cultural representation within this artwork. In the case of this screen, the significance lies in the number nine and the symbolism of the carps. Firstly, the number nine is considered auspicious, as it phonetically resembles the words “eternity” or “longevity” in both Vietnamese and Chinese (Sotheby’s, 2019). Secondly, the carp holds a mythical association with a tale of a carp swimming upstream to reach the Dragon Gate, where it transforms into a dragon (Chen, 2014; Garofalo, 2010). Consequently, carps symbolize perseverance and the attainment of well-deserved success in life. With these cultural references in mind, we can surmise that this screen was created to bestow blessings upon its owners and viewers, embodying notions of longevity, prosperity, and the pursuit of personal growth.

Folding Screens

Coincidentally, four out of five works are presented in the same form – standing screens. Folding screens are traditional functional furniture pieces that usually serve as room dividers to create a private and intimate space in a wide space or backdrops for tea ceremonies (Sanabrais 2012). The practicality and aesthetic potential of folding screens make them an ideal canvas for elaborate paintings. Moreover, the folding nature of the screens enables them to be easily transported and displayed in different settings, making them adaptable for various occasions and environments. By incorporating artistic elements into these functional screens, artists could enhance the aesthetic appeal of any space while providing a visual barrier or focal point.

Another notable aspect of standing screens is the immersive viewing experience they offer. Viewers can move around the freestanding screens, engaging with the artwork from different angles and perspectives. The unfolding panels allow for a sequential exploration of the composition, gradually revealing different aspects of the narrative or scene. This interactive aspect adds depth and dimension to the artwork, captivating viewers and drawing them into visual storytelling.

Conclusion

From these artworks, we can see the differences between the taste of Vietnamese and that of French people. The artworks that remained in Vietnam tended to depict scenes of everyday life, often with unrealistic elements and a focus on local characteristics. Vietnamese cultural representations are more explicit, featuring recognizable local plants, structures, and activities. On the other hand, the artworks created for French audiences incorporate more Western art techniques, resulting in a greater sense of realism and structure. The Vietnamese cultural representation in these works is less prominent, and understanding the context may require knowledge of traditional customs and symbols.

From the discussions in class, we can see that Asian Art is a diverse and culturally rich form of artistic expression that encompasses a wide range of styles, techniques, and themes. It is characterized by a strong emphasis on spirituality, symbolism, and the natural world. Asian Art invites viewers to appreciate the smallest details and find meaning in elements such as colors, plants, and animals. For this chapter in particular, Asian Art serves as a record and reflection of the identities, cultural values, and histories of various Asian countries. Through its intricate techniques and subject matter, Asian Art offers a profound exploration of the region’s artistic heritage and acts as a cultural bridge, fostering understanding and appreciation of Asia’s diverse traditions and creative expressions.

References

ASIANA Fine Asian Art. n.d. “Vietnamese Lacquer Painting – ‘Sơn Mài Bức Tranh.’” ASIANA Fine Asian Art. https://www.asiana-fineart.com/en/insight/vietnamese-lacquer-painting.

Bang, Truc. n.d. “An Introduction to the Lacquer Art of Vietnam.” Eye Gallery. http://www.eyegalleryvn.com/cms/An-Introduction-to-the-Lacquer-Art-of-Vietnam-ptarget-view-pid-34-ppage-3.html

Chen, Anita. 2014. “Carp and Dragons in Vietnam.” USC Digital Folklore Archives. May 16, 2014. http://folklore.usc.edu/carp-and-dragons-in-vietnam/

Christie’s. “Les èternitès (Eternities).” Live Auction 280: Southeast Asian Modern and Contemporary Art (2010). https://www.christies.com/lot/le-pho-vietnam-1907-france-2001-les-5324836/?intObjectID=5324836&lid=1

Denecke, Wiebke, and Nam Nguyen. 2019. “Shared Literary Heritage in the East Asian Sinographic Sphere.” Han Mun Hak Bo 40 (June): 213–51. https://doi.org/10.35496/han.40.7

Duc, Duong, and Mingxin Bao. 2012. “Aesthetic Sense of the Vietnamese through Three Renovations of the Women’s Ao Dai in the 20th Century.” Asian Culture and History 4 (2). https://doi.org/10.5539/ach.v4n2p99

Fullen, Matthew. 2011. “Several Ways in Which Western & Non-Western Art Differ.” EHow. 2011. https://www.ehow.com/info_8479986_several-western-nonwestern-art-differ.html.

Garofalo, Michael. 2010. “Leaping over the Dragon’s Gate, the Carp Leaps through the Dragon’s Gate.” Egreenway. May 1, 2010. https://www.egreenway.com/dragonsrealms/DT3.htm

Insider Business. 2021. “Why Sơn Mài Painting Is so Expensive | so Expensive.” YouTube. January 30, 2021. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=9bi7BDbaUSA&t=157s

Llewellyn, Jennifer, Jim Southey, and Steve Thompson. 2018. “French Colonialism in Vietnam.” Alpha History. Alpha History. June 18, 2018. https://alphahistory.com/vietnamwar/french-colonialism-in-vietnam/

National Gallery Singapore. 2020. “Films on Artmaking in Southeast Asia: Lacquer.” YouTube. June 4, 2020. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=MY4ixRN0V9U

Nguyen, Quan. 2022. “The Flags of Vietnam & Interesting Facts.” Vietnam Trips. August 15, 2022. https://vietnamtrips.com/flags-of-vietnam#iv-cultural-flags-of-vietnam-5-colored-flag.

Proctor, Ann. 2016. “Vietnamese Artists in Paris.” Routledge Encyclopedia of Modernism, September. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781135000356-rem925-1

Safford, Lisa Bixenstine. “Art at the Crossroads: Lacquer Painting in French Vietnam.” The Journal of Transcultural Studies 6, no. 1 (August 3, 2015): 126–70. https://doi.org/10.11588/ts.2015.1.16061

Sanabrais, Sofía. 2012. “The Influence of Japanese Art on Colonial Mexican Painting.” Unframed the LACMA Blog. January 12, 2012. https://lacma.wordpress.com/2012/01/12/the-influence-of-japanese-art-on-colonial-mexican-painting/

Sotheby’s. “Pham Hau: Nine Carps in the Water.” Modern and Contemporary Southeast Asian Art Evening Sale (2019). https://www.sothebys.com/en/auctions/ecatalogue/2019/modern-contemporary-southeast-asian-art-evening-sale-hk0872/lot.1103.html

Taylor, Nora. 1997. “Orientalism/Occidentalism: The Founding of the Ecole Des Beaux-Arts d’Indochine and the Politics of Painting in Colonial Việt Nam, 1925-1945.” Crossroads: An Interdisciplinary Journal of Southeast Asian Studies 11 (2): 1–33. https://www.jstor.org/stable/40860624

Vietnam National Fine Arts Museum. 2021. “National Treasure the Standing Screen Nguyen Gia Tri P1: Coming to the Museum.” YouTube. October 20, 2021. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Fa3HuUFyQ58&t=1s

Wikipedia Contributors. 2021. “Lacquer Painting.” Wikipedia. September 24, 2021. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lacquer_painting

———. 2022. “Nguyễn Dynasty.” Wikipedia. Wikimedia Foundation. May 13, 2022. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Nguy%E1%BB%85n_dynasty

Zhao, Ruby. 2022. “The French Colonial Legacy in Vietnam.” Asia Highlights. November 2, 2022. https://www.asiahighlights.com/vietnam/french-colonial-legacy