Japanese woodcut prints were made cheaply and in large quantities. Their success depended on their popularity, which meant that they had to be interesting to look at or meaningful. With this in mind, it makes sense that prints depicting everyday life would not have been nearly as popular as scenes of legendary heroes, sacred sites, and drama. And yet, there are a number of prints depicting seemingly ordinary subjects, including food. This exhibition seeks to examine why printers would make prints of food, and what they did to make their subjects anything but ordinary.

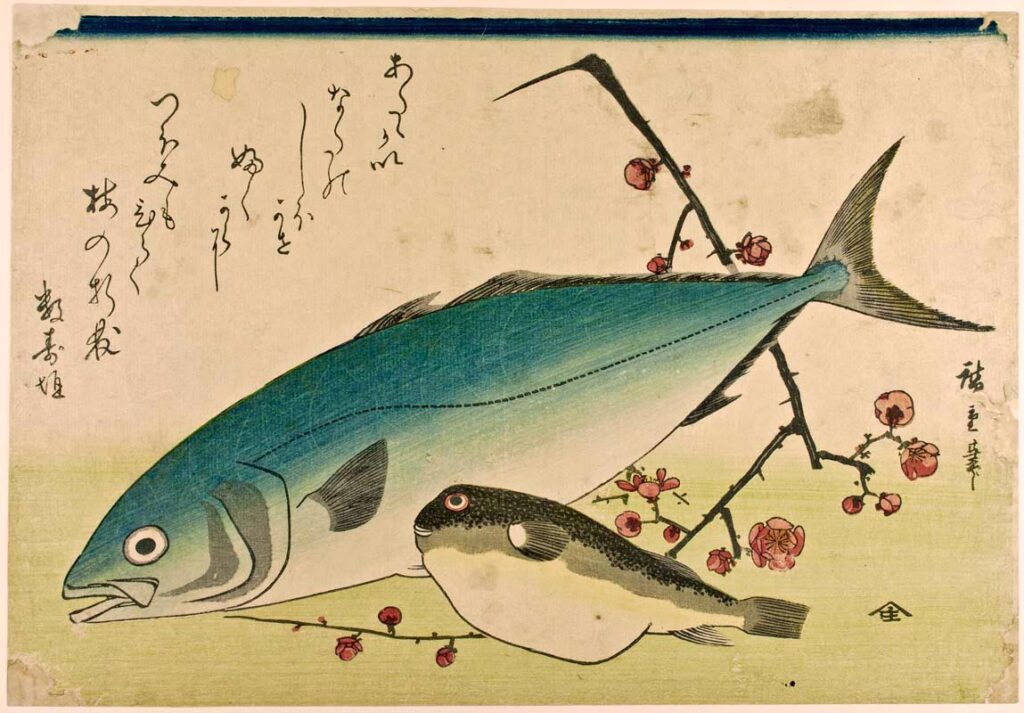

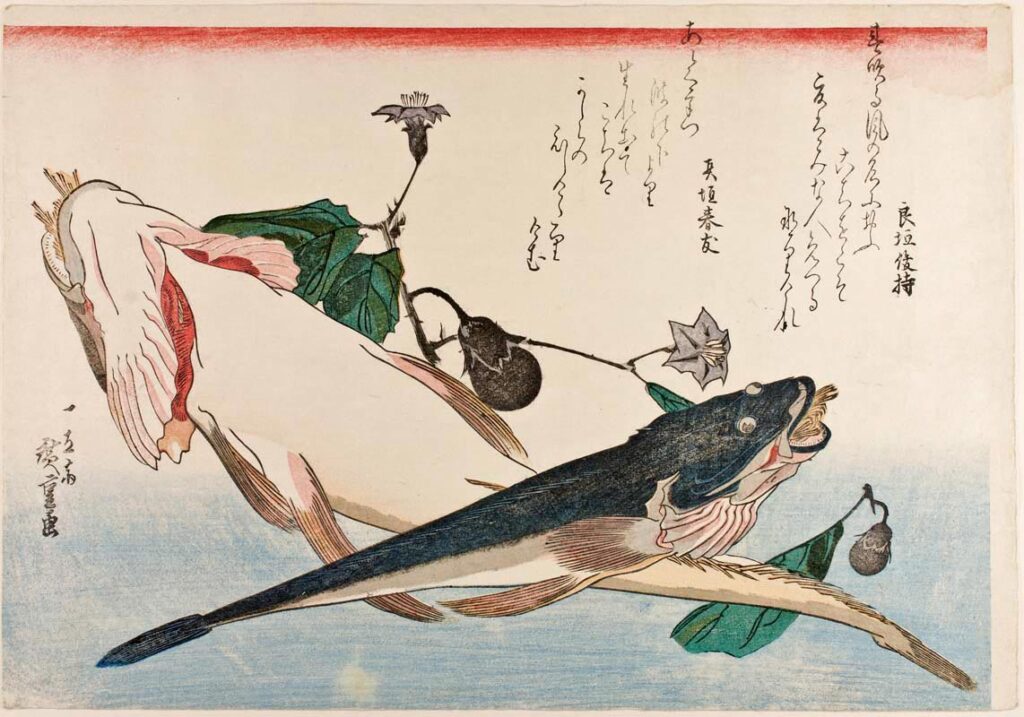

The first three prints are from Ando Hiroshige’s series entitled A Shoal of Fishes. The subjects of these prints are easily mistaken for living natural subjects. However, on closer inspection, these fish are dead. The flatheads in #10 have been stuffed with straw, the flounder in #18 is upside down, and the gurnard in the same print have their fins folded up instead of splayed out like if they were actually swimming. The groupings of fish in each print are also in season at the same time of year: the same time as the plant forms in each print suggest. Late winter before the cherry blossoms are fully open for yellowtail and fugu, midsummer as the eggplants are ripening for flatheads, autumn, when the bamboo leaves are more fibrous (and good for tying together to make dumplings), for flounder and gurnard. These fish are grouped together and displayed as they might be seen at the market, not in the sea. The question then is why these fish are depicted still whole, not as prepared dishes. This was possibly done to connect the food back to nature, to the changing of the seasons, and to the bounty of the sea. The fish in each print are seemingly bursting forth as if fresh from the ocean. This sense of plenty and generosity might have made them attractive pieces for the tokonoma, an alcove in traditional Japanese homes where art is displayed for guests to admire. There is also evidence that prints of food would be displayed in restaurants and inns to advertise what they had to offer. Either way, they convey a sense of hospitality that would make guests feel welcome.

The next two prints were both created by Ryuryukyo Shinsai, but serve two entirely different purposes. The first, which depicts a variety of traditional New Year foods, uses that food for its symbolic value. Each of the foods consumed on the New Year is said to bring a certain blessing upon those who eat it. An orange brings fertility, dried persimmons a long life, and so on. The print is thus not just a picture of food, but a picture of the physical manifestations of the blessings of many children, longevity, a bountiful harvest, and wealth. Hanging this print of spiritually important foods prominently in the home might have been thought to bring these blessings upon one’s household much in the same way that eating the foods did. Given that prints were also often used to wrap gifts in Edo Japan, this print could have been designed as a wrapping for a New Year’s present, meant to confer those same symbolized blessings upon the person receiving the gift.

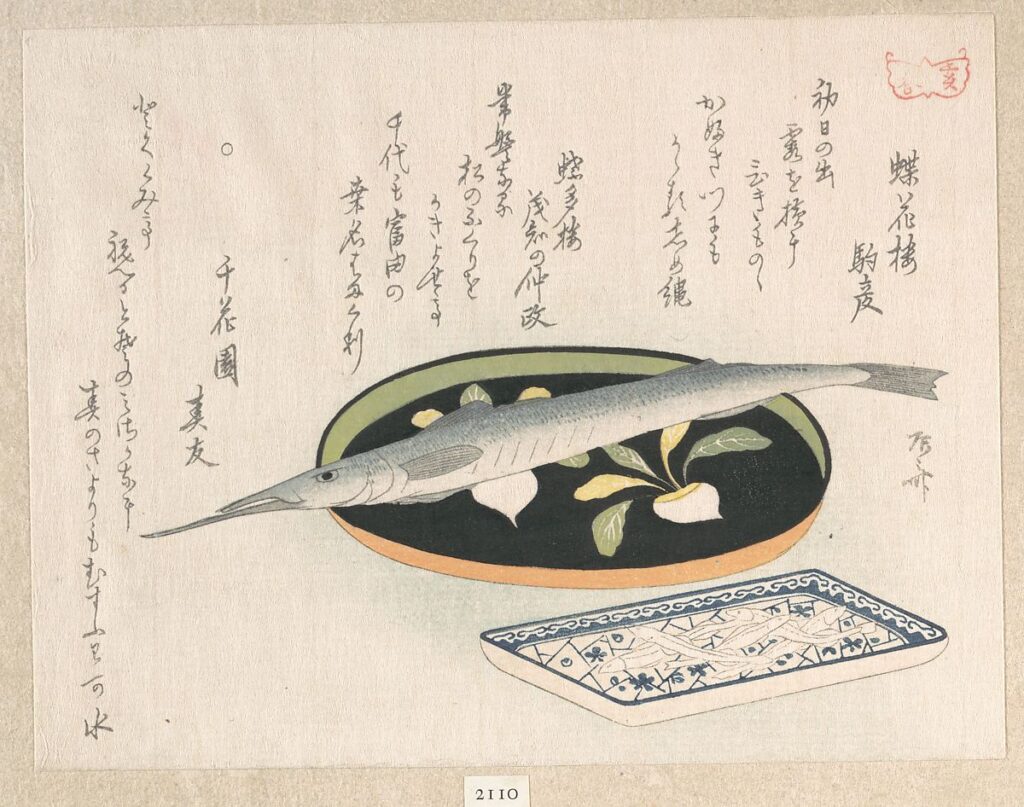

The final print has been difficult to analyze, but possibly demonstrates a third and surprising use of food in ukiyo-e: humor. At this point the whole fish should not look all too out of place in a print about food. What is out of place is the lacquer hassun beneath it. A hassun is a tray used to serve appetizers at formal occasions. Its purpose is to present prepared food to guests, not to hold a whole, raw fish. This anachronism may not be obvious to modern viewers, but for the Edo-period audience, it would have been hard to miss. There are two possible implications of this. There is evidence that in the Edo-period gift-giving culture, fish were sometimes given as gifts, and would have been presented on a nice plate such as this. However, the unprepared halfbeak (which often grow to over a foot long) looks a bit ridiculous hanging over the side of this formal serving dish, which is where the possibility that this was done for comedic effect comes in. This kind of anachronism was apparently a common way to spice up scenes of everyday life. A number of prints exist in which traditional gender roles are switched, for example, making a print depicting tasks traditionally carried out by men more humorous to viewers of the time by filling it with women. In this print, the breaking of well-known food traditions likely serves the same purpose.

One unsolved feature of all five pieces is the writing. It is difficult to read and there is no information readily available about any of the inscriptions online. However, given the consistent length of the lines, these inscriptions are almost certainly poetry, a common addition to ukiyo-e.

Food is an everyday subject, and something that may not seem to make for an interesting print, and yet it is also filled with symbolism, subject to tradition, and connected to both humanity and nature. Leveraging these unique and powerful features of food, artists can make pieces that connote hospitality, bring good fortune, and provide laughter.

Creator: Ando, Hiroshige

Period: Edo

Date: 1840

Culture: Japan

Medium: Woodcut Print

Dimensions: 26×36 cm

Repository: Caroline Black Collection

Description: While this print seems to depict forms from nature rather than food, the Japanese yellowtail and fugu are both in season in late winter, and the cherry branch indicates that it is exactly that time of year, with the blossoms starting to open but not in full bloom. This context implies that the fish are being depicted as food, not animals. The fish are arranged in a sort of bouquet that evokes the bounty of nature and the blessings of food the sea provides. This print might be displayed in a tokonoma (alcove used to display art) as a symbol of hospitality for guests to admire.

Creator: Ando, Hiroshige

Period: Edo

Date: 1840

Culture: Japan

Medium: Woodcut Print

Dimensions: 26×36 cm

Repository: Caroline Black Collection

Description: This print, part of the same 20-print series, is similar to the first. These flatheads, which are in season in summer, the same time as the Japanese eggplants, are clearly dead as their mouths are stuffed with straw (which may have been used to keep them fresh in Japan’s humid summers). They are thus meant to be seen as food rather than natural subjects, but even dead they are still a symbol of plenty and a bountiful catch and harvest, signs of the benevolence of the natural world. With these values in mind, this print would have been a welcoming sight to guests.

Creator: Ando, Hiroshige

Period: Edo

Date: 1840

Culture: Japan

Medium: Woodcut Print

Dimensions: 26×36 cm

Repository: Caroline Black Collection

Description: The gurnard and flounder in this print, part of the same series as the first two images, are both in season in Autumn, meaning once again that they are meant to be seen as the day’s catch. Both are also clearly dead, as the flounder (which have both eyes on one side of their head) is upside-down, and the gurnard has its pectoral fins retracted. Another sign that they are food is the bamboo leaves tied together in the background, suggesting that the fate of these fish might be to make a type of bamboo-leaf-wrapped dumpling called chimaki. The arrangement of these fish makes them appear to be bursting out from the bamboo leaves as if they are too plentiful to be contained, giving this piece, like the others in the series, a sense of bounty and hospitality that would make it a good candidate for the tokonoma.

Creator: Ryuryukyo Shinsai

Period: Edo

Date: 19th century

Culture: Japan

Medium: Woodcut Print

Dimensions: 14×18.9 cm

Repository: The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Description: Each of the foods depicted is traditionally eaten at the New Year in Japan, and each of them symbolizes a blessing the eater wishes to receive. The orange represents fertility, the dried persimmons longevity, the herring roe a bountiful harvest, and the various nuts and seeds symbolize wealth. The foods are piled up in a way that once again suggests abundance. The likely purpose of putting these foods in a print is for their symbolic value. For one to possess a print of these foods around the new year would be akin to possessing the blessings themselves.

Creator: Ryuryukyo Shinsai

Period: Edo

Date: ca. 1815

Culture: Japan

Medium: Woodcut Print

Dimensions: 14.3×18.6 cm

Repository: The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Description: The dishes here are probably the most significant part of the piece. While in other prints it is perfectly appropriate for whole, raw fish to be viewed as food, the dishes complicate this picture. Both are ornately decorated, the lacquer tray with turnips, and the porcelain dish with a floral pattern. The lacquer tray is most likely a hassun, used to serve appetizers to guests at tea ceremonies and other formal gatherings. It would never be used as kitchenware to hold a whole fish, and similarly, though baitfish might have been eaten whole as a snack, halfbeak would never be served or even shown whole to guests, making it an anachronism. This was likely done for comedic effect: anyone familiar with Edo-era formal gathering etiquette and cuisine would have laughed at the absurdity of this print that seems at first glance to depict a boring, everyday subject.

Bibliography:

(Please note that while the Hiroshige prints are cited twice from two different databases, only the ones from the Caroline Black Collection were used as images. The copies in ARTSTOR were used for the background information provided by the database.)

Ando, Hiroshige, A Shoal of Fishes #1, Woodcut Print, 1840, ARTSTOR. Accessed November 5, 2021.

https://library.artstor.org/#/asset/CONNASIAN_106310617037;prevRouteTS=1634417104215.

Ando, Hiroshige, A Shoal of Fishes #10, Woodcut Print, 1840, ARTSTOR. Accessed November 5, 2021.

https://library.artstor.org/#/asset/CONNASIAN_106310616925;prevRouteTS=1634417156953.

Ando, Hiroshige, A Shoal of Fishes #18, Woodcut Print, 1840, ARTSTOR. Accessed November 5, 2021.

https://library.artstor.org/#/asset/CONNASIAN_106310617041;prevRouteTS=1634417204341.

Ando, Hiroshige, A Shoal of Fishes #1, Woodcut Print, 1840, Professor Caroline Black Collection of

Japanese Woodcuts. Connecticut College. Accessed November 5, 2021. https://oak.conncoll.edu/visual/asian-art/Caroline%20Black%20Collection%20of%20Japanese%20Woodcuts/content/_1310113321_large.html.

Ando, Hiroshige, A Shoal of Fishes #10, Woodcut Print, 1840, Professor Caroline Black Collection of

Japanese Woodcuts. Connecticut College. Accessed November 5, 2021. https://oak.conncoll.edu/visual/asian-art/Caroline%20Black%20Collection%20of%20Japanese%20Woodcuts/content/_6598878784_large.html.

Ando, Hiroshige, A Shoal of Fishes #18, Woodcut Print, 1840, Professor Caroline Black Collection of

Japanese Woodcuts. Connecticut College. Accessed November 5, 2021. https://oak.conncoll.edu/visual/asian-art/Caroline%20Black%20Collection%20of%20Japanese%20Woodcuts/content/_8487511373_large.html.

Aomori Prefectural Government. “Flounder.” UMAIMONO AOMORI. Aomori Prefectural Government, March 1, 2019. https://www.umai-aomori.com/products/fish/flounder/.

Busetto, Arielle. “’Oishii Ukiyo-e’: Learning the Roots of Japanese Cuisine from Woodblock Prints.”

JAPAN Forward. Japan Forward, November 12, 2020. https://japan-forward.com/oishii-ukiyo-e-learning-the-roots-of-japanese-cuisine-from-woodblock-prints/.

Chen, Namiko. “Kazunoko (Herring Roe) 数の子.” Just One Cookbook, November 14, 2021. https://www.justonecookbook.com/kazunoko/.

Gurunavi. “8 Popular Ways to Eat Fugu (Japan Pufferfish).” Let’s experience Japan. Gurunavi, 2017.

https://gurunavi.com/en/japanfoodie/2017/04/8popular-ways-to-eat-fugu.html?__ngt__=TT1249afea8005ac1e4ae77eBC7OTWNjoIJHJ7Rh5mMEdr.

Japan Guide. “Kaiseki Ryori.” Japan-guide.com, October 16, 2021. https://www.japan-guide.com/e/e2348.html.

JETRO. “Yellowtail (Buri)/Young Yellowtail (Hamachi).” JETRO. Japan External Trade Organization, 2021. https://www.jetro.go.jp/en/trends/foods/ingredients/buri.html.

M&J Seafood. “When Are Gurnards in Season.” M&J Seafood, 2020. https://www.mjseafood.com/blog/2020-04-30/when-are-gurnards-in-season.

Michelle. “The Meaning behind ‘Osechi Ryori’.” Japan Today. Japan Today, January 4, 2013. https://japantoday.com/category/features/food/the-meaning-behind-osechi-ryori.

Ryuuryuukyo, Shinsai. Halfbeak on a Lacquer Tray and White Baits on a Dish. ca. 1815. The MET. The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Accessed November 21, 2021. https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/54962.

Ryuuryuukyo, Shinsai. Orange, Dried Persimmons, Herring-Roe and Different Nuts; Food Used for the Celebration of the New Year. 1800s. The MET. The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Accessed November 21, 2021. https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/54971.

Seigle, Cecilia S. “Gift Exchanges in Edo Castle.” Scholarly Commons. University of Pennsylvania, August 1, 2012. https://repository.upenn.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1005&context=ealc.

Shiro’s Sushi Restaurant. “New in April 2018.” Shiro’s Sushi, April 2018. https://shiros.com/new-in-april-2018/.

Sperss, Phil. “How to Prepare Bartail Flathead for Nigiri Sushi.” La Petit Noisette, August 14, 2019. https://lapetitnoisette.com/2019/08/14/how-to-prepare-bartail-flathead-gochi-%E3%83%9E%E3%82%B4%E3%83%81-%E3%82%B3%E3%83%81-%E9%AF%92-for-nigiri/.

Taggart, Emma. “10 Facts about Utagawa Hiroshige: The Last Great Master of Japanese Woodblock Printing.” My Modern Met. My Modern Met, August 10, 2021. https://mymodernmet.com/utagawa-hiroshige/.

Thompson, Sarah. “The World of Japanese Prints.” Philadelphia Museum of Art Bulletin 82, no. 349–350 (1986): 1–5, 28–39. https://www.jstor.org/stable/3795440.

Ung, Judy. “Facts about Japanese Chimaki.” The Spruce Eats. The Spruce Eats, April 27, 2019. https://www.thespruceeats.com/chimaki-japanese-dumplings-2030931.

West, Mark D. “Haley and the Blowfish.” Washington University Global Studies Law Review 8, no. 2 (2009): 427–42. https://heinonline.org/HOL/Page?collection=journals&handle=hein.journals/wasglo8&id=436&men_tab=srchresults.