I had first encountered Asian art when I accidentally stumbled into the Chu Reading Room one afternoon my freshman year. I was curious about the sense of minimalism in the pieces, the peaceful subject matter of the art, and who Charles Chu was. When I had the opportunity to take this course, I was immediately inspired to learn more about who Professor Chu was, what sort of art he made, and what inspired him to curate a collection of Asian art for Connecticut College. I took the opportunity to use this project as a way to learn more about Charles Chu, the art he produced, and the pieces he gratefully donated to the college. In my research, I plan to dissect different works of Charles Chu and observe the inspiration and meaning behind them.

Charles Chu was a Chinese American artist who was born in Guangzhou, China in 1918 and immigrated to the United States in 1935. He studied art at the Art Students League of New York and went on to have a successful career as a painter, educator, and curator. Chu’s artwork was influenced by the abstract expressionist movement and often incorporated elements of Chinese calligraphy and symbolism. He was particularly known for his use of animals and inscriptions in his paintings, which added an additional layer of meaning and visual interest.

In addition to his artistic career, Chu was also a respected professor of art at Connecticut College in New London, where he taught for over two decades. Through his teaching and mentorship, Chu inspired and influenced many aspiring artists, leaving a lasting impact on the art world. He was also a curator and art critic, and he helped to promote the work of other Asian American artists.

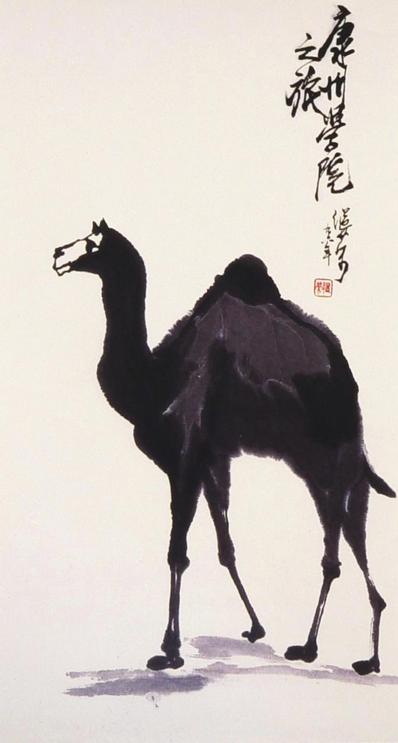

The first piece I examined was Camel, by Charles Chu, from 1996. This painting is minimalist, mono-colored, and features a single-centered subject. The large scale of the image gives the camel a grand sense of power, strength, and resilience. Camel depicts the Connecticut College mascot, the camel, and was created for the college community. The strength of the camel is representative of the student body here at the college. The inscription, “The Journey Continues,” helps create the attitude of perseverance and power to push forward. Camels are generally known as large, even-toed ungulates that are well adapted to arid environments. They are famous for their ability to store water and withstand harsh conditions, making them an essential mode of transportation along the Silk Road trading network in ancient times. The Silk Road was an extensive trade route that connected China, Central Asia, and the Mediterranean, and camels played a vital role in the transportation of goods such as silk, spices, and precious metals.

Charles Chu, Camel, 33.2 x 66.3 cm 13.0 x 26.1 inches, Ink on paper, 1996, Crozier-Williams Center, Connecticut College, Little Frog Gallery, (Photo from Little Frog Gallery)

Inscription “Connecticut College – The Journey Continues”

The second piece I observed is Earth Day 1995 by Charles Chu. The single-subject painting displays a pop of color that was not seen in the image of the camel. The rooster sits in a flashy, pompous style, almost as if posing for an image. The light touches of color help bring the animal to life. This piece was created to celebrate Earth Day here at Connecticut College in 1995, as indicated by the work’s inscription. The piece sets the tone of nature with its warm, earth-toned colors. The colors are also reminiscent of a New England Springtime bloom

Inscription: Life comes and goes. The earth creates the timeline. Rich or poor, we all share the earth. After every severe winter warm spring comes.

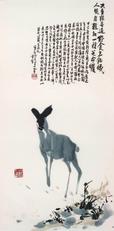

Charles Chu’s compositional style was marked by a few distinct characteristics that can be observed throughout his body of work. One of these was the placement of inscriptions, which tended to appear on the top or top right of his paintings. These inscriptions were often written in bold, calligraphic script and were sometimes accompanied by small symbols or images. They added an additional layer of visual interest to the paintings and could be seen as a nod to Chu’s Chinese heritage, which emphasized the importance of calligraphy and the written word in art.

Another defining feature of Chu’s work was his frequent use of animals, which were often depicted facing or walking toward the left side of the canvas. This directional bias could be interpreted as a deliberate choice on Chu’s part, as it created a sense of movement and progression within the composition. By placing the animals on the left side of the canvas, Chu also allowed for negative space on the right side, which could be used to balance out the composition or draw attention to other elements of the painting.

Additionally, Chu’s paintings often featured bold, gestural brushstrokes and vibrant colors, which conveyed a sense of energy and movement. His abstracted forms and expressive mark-making added a sense of dynamism and vitality to his compositions, making them feel dynamic and alive.

The next piece I chose by Chu is Roosters and Chicks that was created in 1984. This piece depicts more than one subject that is spread all about the piece; not just in the center. Similar to the last piece, this one depicts a bright pop of color to bring the scene to life. The order of the birds goes from biggest to smallest from the top to the bottom respectively. Perhaps, they are also in order by age. This image contains similar subject matter to the last piece. This one displays both roosters and chicks, however, which adds an element of family, brotherhood (or perhaps sisterhood) to the scene. The colors of this artwork are even warmer than the last piece, representative of a semi-dark Autumn season.

Inscription: If there are chickens in the world there will be eggs. To lay and brood eggs is natural. Some chickens loudly announce their intention to lay eggs, and cluck even more loudly after they have laid an egg. Some loyal chickens lay eggs quietly. The chicken coop is far from where the nobles live, but the rich are grateful for their banquet.

The penultimate work in my curated collection is Deer by Charles Chu from 1996. This piece depicts a single subject near the center of the canvas. Similar to the camel, this piece uses very little to no color. The only color can be seen in the greens of the landscape, and the body of the deer has a slight tint of blue. This piece, unlike the others, has a very long inscription. The deer is a subtle and delicate creature, and the scene here depicts nothing less. The animal appears to be hopping along with a sense of bliss, serenity, and innocence. The minimal use of color helps add a peaceful sense to the scene. The calm scene combined with the long inscription suggests that the physical complexity of the scene does not necessarily correlate with the complexity of the story or meaning behind it. The artist’s inspiration for the painting was to advocate against the hunting of innocent deer, which had proliferated in the area of Bluff Point. He meant to convey this innocence in the animal.

Inscription: To be born was not our decision. In the wilderness we search for food. We don’t understand why people hate us. With a shot, life is finished.

The final piece I chose to include is Turtles by Charles Chu from 2000. This scene appears more complex than the other pieces I have curated. The image depicts more than one (three to be exact) turtles that serve as the primary subject. The scene also contains landscape snapshots on the top and bottom of the turtles. The turtles themselves appear to be congregating on a mini island. The inscription is carefully tucker away to the right of the turtles. This image uses a slight tint of colors throughout the piece. Turtles often represent an easy-going, patient tone in their depictions. This scene similarly shows two turtles calmly waiting for the other to join. This painting creates a sense of community and inclusiveness that is likely representative of the Connecticut College population. Charles Chu saw this happen in early spring at the Connecticut College Arboretum and got inspiration for the painting according to Little Frog Gallery.

Inscription:

When the earth’s energy rises, Thousands of creatures come back to life. Turtles are now sunning in the lake.

They are winter guests living at the bottom of the water year after year, avoiding the noise of human beings.

In order to gain a deeper understanding of the significance of animals in Chinese art, it is helpful to consult multiple sources and consider different perspectives. Two such sources are the books “Decoded Messages: The Symbolic Language of Chinese Animal Painting” by Hou-mei Sung and the “The Zoomorphic Imagination in Chinese Art and Culture” edited by Jerome Silbergeld and Eugene Yuejin Wang.

Sung’s book focuses specifically on the symbolism of animals in Chinese painting, and it emphasizes the importance of understanding the cultural context in which the artworks were created. According to Sung, animals in Chinese painting were not just decorative elements but were imbued with deep symbolic meaning. Each animal had a specific set of associations and could be used to convey different ideas or emotions. For example, the tiger was often associated with strength and courage, while the rabbit was seen as a symbol of fertility and longevity.

Silbergeld and Wang’s book takes a broader approach, exploring the use of animals in Chinese culture more broadly. They argue that animals have played a central role in Chinese art, literature, and folklore for thousands of years, and that they continue to hold significance in contemporary Chinese society. The book examines various aspects of animal imagery in Chinese culture, including the ways in which animals have been used to represent political power, social hierarchy, and religious beliefs.

As a third voice, I believe that both of these perspectives are valuable in helping us to understand the significance of animals in Chinese art. While Sung’s focus on the symbolism of individual animals is certainly illuminating, it is important to recognize that animal imagery has been used in many different ways in Chinese culture over time. By considering a range of perspectives, we can gain a more holistic understanding of the role that animals have played in Chinese art and culture, and the ways in which they continue to shape our understanding of the world around us.

Throughout history, animals have been used as a powerful tool for storytelling and emotional expression. Charles Chu, an accomplished artist and professor of art and languages at Connecticut College in New London, recognized the potential of animals as a means of exploring the natural world and conveying complex emotions. Chu’s compositions often feature inscriptions on the top or top right, and animals facing or walking towards the left, among other stylistic choices. As noted by the Little Frog Gallery website, Chu’s works “blend Western techniques and Chinese techniques” to create a unique visual language that is both rich in symbolism and aesthetically compelling.

However, Chu’s use of animals in his work goes beyond mere aesthetics. Each of his paintings is a narrative in and of itself, crafted to convey a specific emotion or story. As a storyteller, Chu used animals as vehicles to explore and express his ideas, delving deep into the symbolism and cultural meanings of each creature he depicted. By doing so, he created a body of work that is not only visually stunning but also deeply meaningful.

The camel reflects a mammal, historically relevant as a beast of burden and transportation in desert regions, including along the Silk Road trade routes. “Earth Day 1995” and “Roosters and Chicks” present avian creatures, historically relevant in many cultures for their symbolism and association with farming and agriculture. “The Deer” depicts a mammal, historically relevant in many cultures for their symbolism and association with nature, beauty, and hunting. Turtles are aquatic, and historically relevant in many cultures for their symbolism and association with longevity, wisdom, and perseverance.

In conclusion, Chu’s contributions to the art world are not limited to his paintings alone. As a professor at Connecticut College for over two decades, he inspired and mentored countless aspiring artists, leaving a lasting impact on the field of art. His use of animals in his work reflects a larger cultural trend in which animals have been used to represent everything from political power to religious beliefs. By tapping into this rich tradition, Chu was able to create works that are both timeless and deeply rooted in Chinese culture. In short, Charles Chu was not just an animal painter, but a master storyteller who used animals to communicate his ideas and emotions to the world.

Reading list:

Chinese Brush Paintings by Charles Chu, www.littlefrog.com/. Accessed 8 May 2023.

Ricklin, Lois Webster. “Alumni Memories.” Connecticut College, www.conncoll.edu/in-memoriam/charles-chu/alumni-memories/. Accessed 8 May 2023.

Braunstein, Mark. “The Chu-Griffis Art Collection at Connecticut College.” Chu-Griffis Art Collection, oak.conncoll.edu/visual/asian-art/Chu-Griffis/index-main.html. Accessed 8 May 2023.

Rogers, Brian. 2009. Review of Chu-Griffis Collection of Asian Art. Linda Lear Center for Special Collections and Archives. Connecticut College. 2009.

“Chu Griffis Collection of Art.” Chu-Griffis Collection of Asian Art, conncoll.lunaimaging.com/luna/servlet/ConnColl~2~2. Accessed 8 May 2023.

Sung, Hou-mei. The Symbolic Language of Chinese Animal Painting. Cincinnati, Ohio: Cincinnati Art Museum; New Haven: Yale University Press, 2009.

Silbergeld, Jerome, and Eugene Yuejin Wang, eds. The Zoomorphic Imagination in Chinese Art and Culture. Honolulu: University of Hawaiʻi Press, 2016.