Analyzing the cultural idealisms that lie between the philosophical understanding of life and death reveals a prevalent cultural theme: relativity. This circulating theme permeates the perspectives and interpretations surrounding the concepts of existence and mortality within a given cultural context. In the early traditional era of Japanese history, specifically the Kamakura period, death was viewed as something not to be grieved, but rather something to be celebrated. Dieties and spirit guides surround the body of the dead or dying to ensure a proper rebirth in the afterlife, and the artistry of these scenes are nothing short of reassuring for its viewers. Shifting toward post-war modern Japanese photography, the ideas about life and death seem to be mixed into an interwoven fabric of impermeability. Not much is known about where we go when we pass, and this project sought to understand how early Japanese art attempted to portray the unspeakable using culturally resonant symbolism and imagery.

Gelatin-silver photograph 17 ½ x 23 ¾ in. (44.5 x 60.4 cm).

The Cleveland Museum of Art.

This photo taken by Sugimoto Hiroshi depicts a specific place in the Carribean where the clear horizon divides the vast expanse of the sea and the sky. Philosophically speaking, this image may exist to represent a liminal space, a threshold between the known and unknown, or the finite and infinite. It pressures the viewer to explore the duality of life and death with a conceptual approach one may not fully understand, emphasizing the importance of the uncomfortability. Dana Friis Hansen wrote about the image in an excerpt taken from Internalization, Individualism, and the Institutionalization of Photography, “For the viewer, the discovery of something grander than the seascape genre gradually surfaces as we realize that there is no trace of humankind present in these wide vistas, nor any detail of time or place, making them utterly open voids.” The interpretation of this image falls entirely upon the viewer and his or her current state of percpetion, which I believe is the intent of art as its own language, however, there is no denying the presence of dualism in this image.

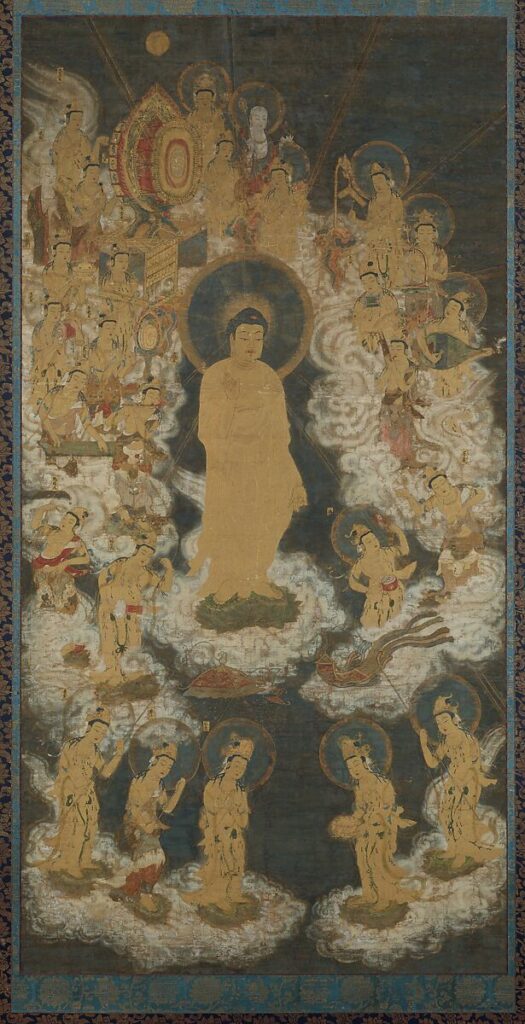

Artist: Unidentified artist / Period: Nanbokuchō period (1336–92) / Date: late 14th century / Culture: Japan / Medium: Hanging scroll; ink, color, and gold on silk/ Dimensions: Image: 65 3/4 × 33 1/2 in. (167 × 85.1 cm)

Overall with mounting: 8 ft. 3 1/2 in. × 39 1/2 in. (252.7 × 100.3 cm)

Overall with knobs: 8 ft. 3 1/2 in. × 42 1/4 in. (252.7 × 107.3 cm)

Classification: Paintings / Credit Line: Gift of Abby Aldrich Rockefeller, 1942 / Accession Number: 42.25.37

Artist: Unidentified artist / Period: Kamakura period (1185–1333) / Date: 14th century / Culture: Japan / Medium: Hanging scroll; ink, color, and gold on silk /

Dimensions: Image: 77 1/2 × 74 1/4 in. (196.9 × 188.6 cm)

Overall with mounting: 10 ft. 10 in. × 77 1/2 in. (330.2 × 196.9 cm)

Overall with knobs: 10 ft. 10 in. × 86 1/4 in. (330.2 × 219.1 cm)

Classification: Paintings / Credit Line: Rogers Fund, 1912 / Accession Number: 12.134.10

As we can tell from the two images given above, both of which depict the religious idealisms surrounding the culture of death in the Kamakura period, traditional Japanese artistry was largely mythological. In the first image we see Buddha descending from heaven to walk alongside the dying and ensure a proper rebirth in the afterlife, and the second image depicts the death of Buddha himself as he reaches his ultimate state of enlightentment. This emphasizes the impact of religion on early traditional Japanese artworks, and also tells a story about an old culture whose dreams were heavily rooted by beliefs and hopes. Animals, dieties, and companions gather by the side of the two figures, whether cheerful or somber, they all join to wish the dying a comfortable passage. All in all, traditional artwork displays the cultural emphasis on religion and the afterlife, which soon loses its original meaning as we begin to progress to more modern approaches.

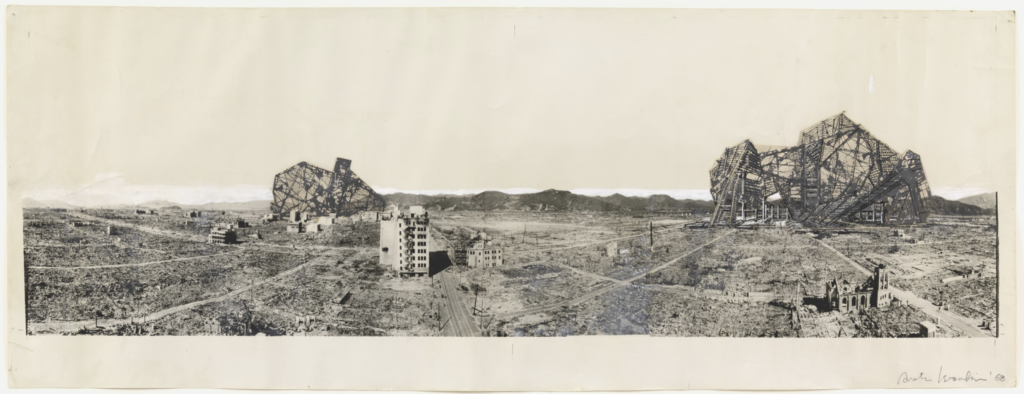

Medium: Ink and gouache with cut-and-pasted gelatin silver print on gelatin silver print / Dimensions: 13 7/8 x 36 7/8″ (35.2 x 93.7 cm) / Credit: Gift of The Howard Gilman Foundation

Object number: 1205.2000 / Copyright: © 2023 Arata Isozaki.

In the first postwar image titled Re-ruined Hiroshima, by Isozaki Arata in 1968, the aftermath of the tragic nuclear fallout is displayed while a modern attempt for early urbanization is imagined. The dichotomy between complete destruction and the imagination for what could be almost entirely speaks for itself, like the first of a crocus blossom peeking out from the frosted spring ground. Just like the human experience, obliteration is inevitable, but it is the human spirit that allows for reincarnation in this world. Isozaki Arata spoke about the image and stated,“The ruins that formed my childhood environment were produced by acts of sudden destruction…wandering among them instilled in me awareness of the phenomenon of obliteration, rather than a sense of the transience of things. Future cities are themselves ruins. Our contemporary cities…are destined to live only a fleeting moment. Give up their energy and return to inert material. All of our proposals will be buried. And once again the incubation mechanism is reconstituted. That will be our Future.” The key idea behind obliteration is that there is a cyclical nature to life, and although nonexistence is rarely spoken of with our neighbors and colleagues, it has consistently been represented in art media as a reminder of lifes fragility, especially in this image.

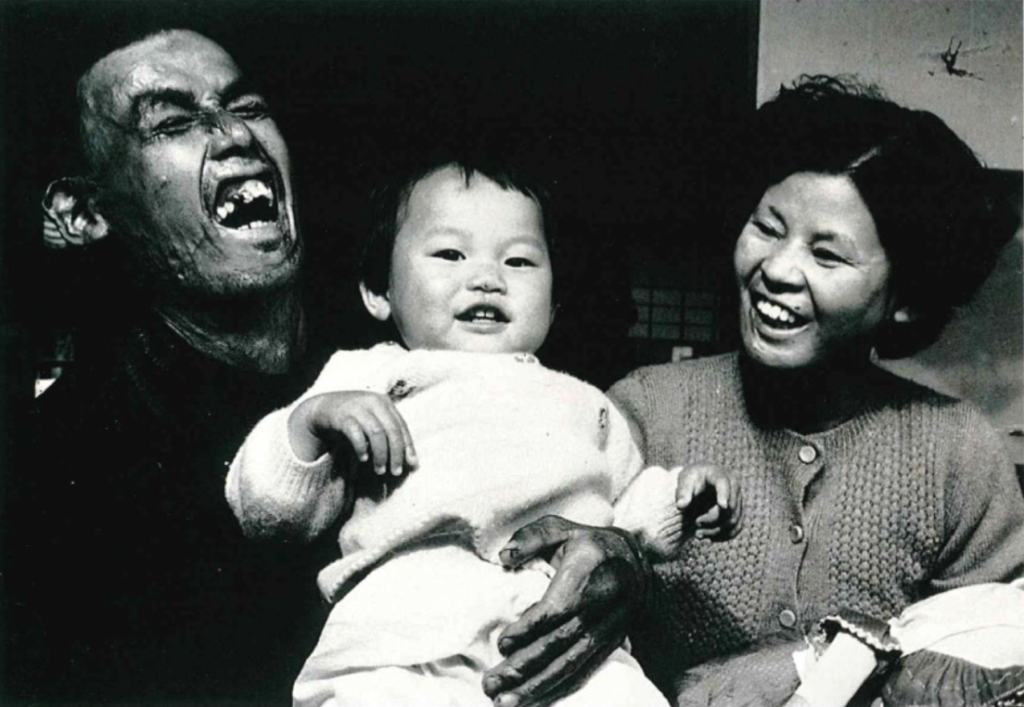

Gelatin-silver photograph, 9 1/2 9 ½ x 14 ¼ in. (24 x 36 cm).

Domon Ken Museum of Photography, Sakata.

The fragility in life is a beautiful theme in and of itself… It is a tapestry woven with threads of contradiction, harmony, and perpetual change. Represented by Domon Ken’s Mr. and Mrs. Kotani: Two Whom Have Suffered from the Bomb, the raw emotions of the characters tell a story about how the duality between life and death is an intricate and inseperable aspect of the human experience. Some may define it as a binary opposition, as displayed in Sugimoto Hiroshi’s photography, while others may view it as a dynamic interplay that defines the very essence of our human experience. The parents who seem to have just missed death’s grasp by a hair clutch onto their healthy baby with rejoice in their reunion. Ken’s piece is heavily influential as it embraces the beauty in life’s fleeting moments and attempts to find meaning in the continuous ebb and flow of existence.

Wood, metal, glass mirrors, plastic, acrylic paint, and LED, the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, Museum purchase funded by the Caroline Wiess Law Accessions Endowment Fund. © Yayoi Kusama

Lastly, Yayoi Kusama’s Aftermath of Obliteration of Eternity exhibition attempts to redirect our focus to traditional Japanese depictions of life and death, where there existed a major emphasis on the afterlife and reincarnation. Guests at this exhibition were to step into an enclosed room filled with hundreds of lights reflected off a mirrored space, and this seems to be Kusama’s attempt to portray the ungraspable concept of infinity. It also conveys the sensation of timelesness and impermanence, and leaves a certain hopefulness for what we believe of the afterlife to feel like. It seems as though the significance of religious narratives regarding the afterlife appeared to wane in modern Japanese photography for a period, only to be rekindled in Kusama’s exhibition.

In the realm of post-war modern Japanese photography, the duality of life and death has been heavily represented as artists are known to emphasize the beauty of lifes fragility by creating metaphors for transience, emptiness, and dislocation in their works. The mysteries of what lies beyond death became elusive, as modern arts seem to shift its attention to the meaning of life itself. Yet, in the broader landscape of modern Japanese visual arts, the portrayal of life and death is often veiled, leaving the interpretation to the discretion of the viewer. All in all, unlike the explicit depictions in traditional Japanese art, the contemporary approach seems to leave the contemplation of life’s ephemeral nature to the viewer as a personal journey, representing the evolving nature of cultural perspectives on mortality.

Bibliography

Arata Isozaki. re-ruined Hiroshima, project, Hiroshima, Japan … – MOMA. Accessed December 3, 2023. https://www.moma.org/collection/works/816.

Artist, Unidentified. “Unidentified Artist: Welcoming Descent of Amida and Bodhisattvas: Japan: Nanbokucho Period (1336–92).” The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Accessed December 3, 2023. https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/45249.

“Death of the Historical Buddha (Nehan-Zu): Japan: Muromachi Period (1392–1573).” The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Accessed December 3, 2023. https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/45417.

Hiroshi Sugimoto. “Caribbean Sea, Jamaica.” Cleveland Museum of Art, August 14, 2023. https://www.clevelandart.org/art/1994.22.

Kotaro, Iizawa. The Evolution of Postwar Photography, n.d.

“Yayoi Kusama ‘Aftermath of Obliteration of Eternity’ (Ongoing).” The Museum of Fine Arts, Houston. Accessed December 3, 2023. https://www.mfah.org/exhibitions/galleries/kusama-aftermath-obliteration-eternity.