The art of Japan is iconic. Everybody can look at Japanese artwork and instantaneously know it’s Japanese. The art may have a distinct and signature style recognizable by all, but its distinctive nature can hold well without that style. Japanese art is unique because it couldn’t have come from anywhere but Japan. Others can imitate the style and look all they want, but they will never capture that distinct quality as long as they lack the distinct environment of Japan itself.

All countries are unique in their geography and location, and that unique location results in unique qualities exclusive to said country. It affects the climate, time of day, environment, terrain, wildlife, and weather patterns, among others, and Japan’s geography is unlike any other’s. To provide context, Japan is an island country formed by volcanic means with a predominantly mountainous territory and many volcanoes. The land lacked any animal life. Due to the archipelago being situated along the Ring of Fire, where several tectonic plates meet, Japan is vulnerable to natural disasters such as earthquakes, tsunamis, and volcanic eruptions. In addition, the region tends to have hot and humid summers, save for Northern Japan. These qualities would shape Japan as a whole, and Japanese artwork would solidify these qualities into the signature imagery of Japan as a country.

Mount Fuji; Making an Icon of a Mountain

Procession Passing Mt. Fuji, by Kitagawa Utamaro (ca. 1794). Color Woodcut Triptych. 37.2 x 75 cm (14.64567 x29.5276 in.) Japan, Edo Period. Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco.

Under the Wave off Kanagawa (Kanagawa oki nami ura), also known as The Great Wave, from the series Thirty-six Views of Mount Fuji (Fugaku sanjūrokkei) by Katsushika Hokusai (ca. 1830-32.) Woodblock print; ink and color on paper. 10 1/8 x 14 15/16 in. (25.7 x 37.9 cm.) Tokyo, Japan. Edo period (1760–1849.)The Art Institute of Chicago.

Mount Fuji serves as the cultural icon of Japan. Much like the Eifel Tower, The Great Wall of China, and the Pyramids of Giza, Mount Fuji has become synonymous with its country. It might even be the first thing that comes to mind whenever somebody thinks of Japan, and the mountain would not have reached this status in the world without Japan embracing it as an icon. Mount Fuji was always an immensely popular art subject in Japan, extending beyond paintings and woodblock prints to mediums such as poetry and pottery. It was the subject of Katsushika Hokusai’s famous woodblock print collection, “Thirty-Six Views of Mount Fuji,” best known for its iconic piece, “The Great Wave off Kanagawa.” The Great Wave is one of, if not the most famous piece of Japanese art ever, and the collection’s popularity would further the popularity of Mount Fuji worldwide.

Hiroshige; Snapshots into the Past

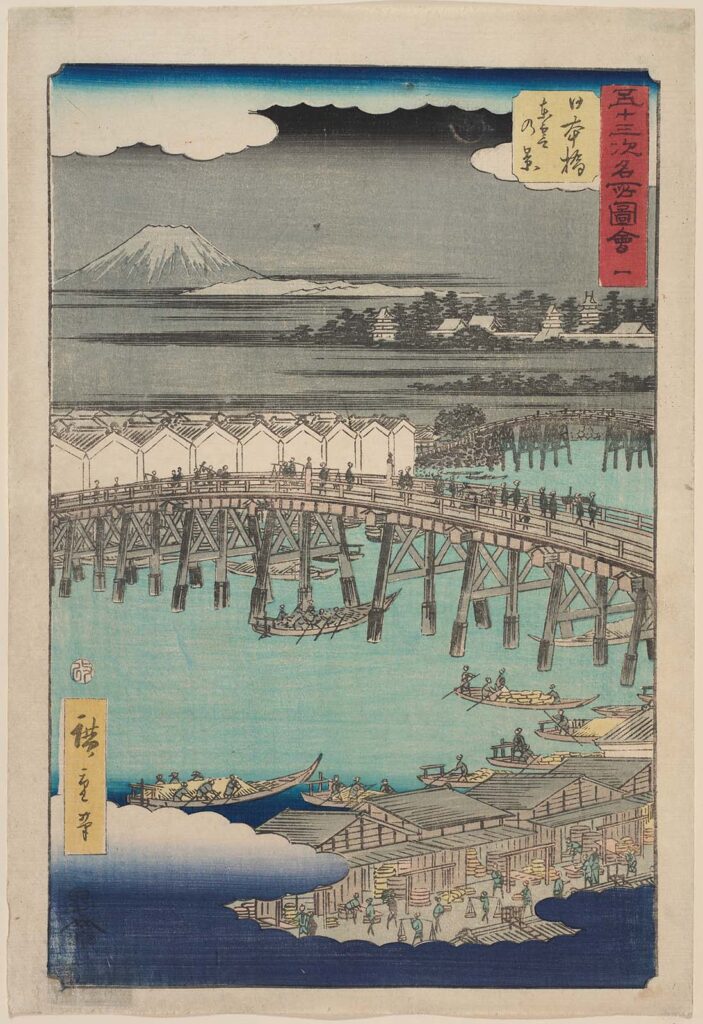

No. 1, Nihonbashi: View of Dawn Clouds (Nihonbashi, Shinonome no kei), from the series Famous Sights of the Fifty-three Stations (Gojûsan tsugi meisho zue), also known as the Vertical Tôkaidô, by Utagawa Hiroshige (ca. 1855.) Woodblock print (nishiki-e); ink and color on paper. 37.2 x 25.3 cm (14 5/8 x 9 15/16 in.) Japan, Edo period. William Sturgis Bigelow Collection.

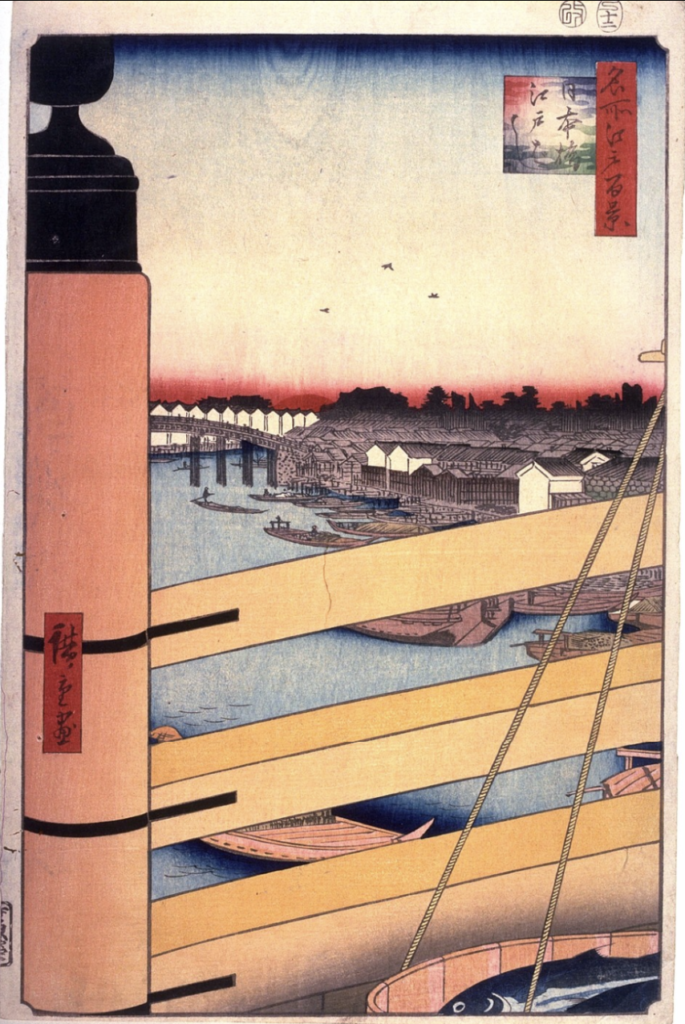

Nihonbashi and Edo Bridge (Nihonbashi Edobashi), from the series One Hundred Famous Views of Edo (Meisho Edo hyakkei)

by Utagawa Hiroshige (ca. 1857.) Color woodblock print (nishiki-e); ink and color on paper. 14 5/8 × 10 1/16 in. (37.2 × 25.6 cm.) Japan, Edo Period. Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco.

The most recurrent artist is Utagawa Hiroshige, known for his signature woodblock series, such as The Fifty-three Stations of the Tōkaidō, The Sixty-nine Stations of the Kiso Kaidō, and One Hundred Famous Views of Edo. Each collection is vital in providing a snapshot of Japan’s past, for each piece is based on real-world locations. The Five Routes of Edo (Gokaidō) were the centrally administrated routes connecting the shōgun’s headquarters in Edo (now modern-day Tokyo) to the other provinces in the Edo period. The most vital of the five was the Tōkaidō Road, linking Edo to Kyoto. Post stations were set up throughout the roads as rest stops for weary travelers, and those post stations were the subjects of Hiroshige’s collections. Hiroshige traveled the Tōkaidō from Edo to Kyoto as part of an official delegation delivering horses to be presented to the imperial court as an annual symbolic gift from the shōgun. The landscapes of the journey struck a chord with Hiroshige, and he created various sketches of his sightings throughout the journey and the way back. Upon returning to Edo, he immediately got to work on the first prints from The Fifty-Three Stations of the Tōkaidō. He would later make a similar collection focusing on the 69 stations of the Nakasendō route, called “The Sixty-nine Stations of the Kiso Kaidō.” Hiroshige’s art embraces the land of Japan, showing views and locales that could never be found elsewhere.

The Bountiful Sea

Lobster and Shrimp, from an untitled series known as Large Fish by Utagawa Hiroshige I (ca. 1832-33) Woodblock print (nishiki-e); ink and color on paper. 25.4 x 36 cm (10 x 14 3/16 in.) Japan, Edo Period. The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

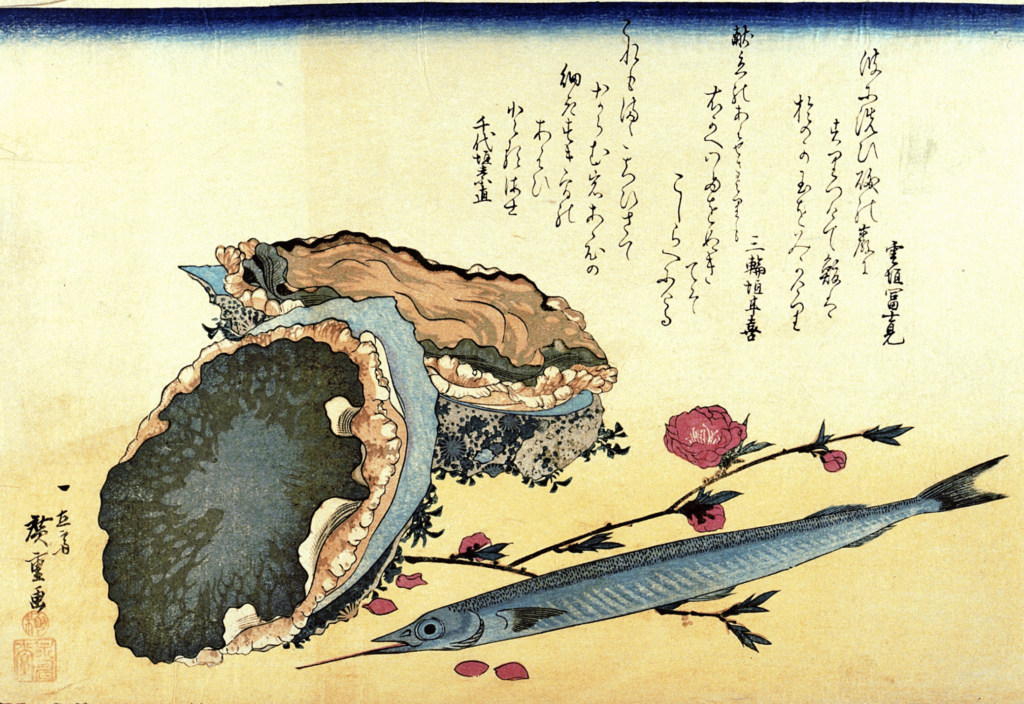

Abalone, Needlefish, and Peach Blossoms, from an untitled series known as Large Fish by Utagawa Hiroshige I (ca. 1832-33) Woodblock print (nishiki-e); ink and color on paper. 26.5 × W. 37.7 cm (10 7/16 × 14 13/16 in.) Japan, Edo Period. Wetmore Print Collection, Art History Dept, Cummings Arts Center, Connecticut College, New London,

It is a basic fact that fish have a long and coveted history with Japan. As mentioned earlier, Japan lacked any animal life due to being an island. In addition, the predominantly mountainous region was unfit for pastures needed for cattle and the cultivation of crops, and a mere 15% of the land had good enough conditions to support farming. Although Japan eventually took up rice as its primary crop, agriculture was not a dependable food source for various reasons- climate change, seasonal change, and, most importantly, the country’s propensity to natural disasters. The land was all too unsustainable for making food, but the surrounding ocean compensated for this. Therefore, Japan would take to the sea for food. Since the country essentially had exclusivity to the surrounding sea as an island, fishing would become the country’s essential source of sustenance. The country’s image is embedded in fishing, the ocean, and aquatic life to this day, and the art of Japan solidified this image.

One of Hiroshige’s lesser-known collections is Uozukushi (Every Variety of Fish.) As the name says, the Uozukushi is a woodblock print collection of fish, and each entry is dedicated to a particular fish, save for the lobster and shrimp, being the only shellfish featured. This is not to be mistaken for “Gyotaku,” a dedicated printing form where fish are physically printed onto paper with ink as a method of cataloging among fishermen. Not only were fish bountiful, but their diversity served as an excellent subject in art, and their crucial purpose in Japan was awarded in countless ways.

The End

The art of Japan has unashamedly and proudly embraced its origins. In the case of Mount Fuji, the art has even made icons into the icons they are today. That unabashed appreciation for its country and the land they live on makes Japanese art recognizable and distinct. It couldn’t have come from anyplace else. I believe that open appreciation is what makes Asian art what it is.

IMAGE/IMAGE INFO CREDITS

Kitagawa Utamaro, Asian; Far East Asian; Japanese, 1754 – 1806. circa 1794. Procession Passing Mt. Fuji. Prints. Place: Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco, San Francisco, California, USA, Katherine Ball Collection, 1964.141.1220a-c, http://www.thinker.org/. https://library.artstor.org/asset/AMICO_SAN_FRANCISCO_103847221.

Katsushika Hokusai. 1826-1836. The Great Wave off Kanagawa (Kanagawa oki nami ura), from the series “Thirty-six Views of Mount Fuji (Fugaku sanjurokkei)”. Place: The Art Institute of Chicago, Clarence Buckingham Collection. https://library.artstor.org/asset/AWSS35953_35953_41726495.

Utagawa Hiroshige, Japanese, 1797-1858; Kichizō Tsutaya, publisher, Japanese. 1855.7. View with dawn clouds, Nihon Bridge, Pictures of the fifty-three stations of the Tokaido, recto. print. https://library.artstor.org/asset/AWSS35953_35953_32667261.

Hiroshige, Asian; Far East Asian; Japanese, 1797 – 1858. 1857. Edo Bridge from Nihon Bridge (Nihombashi edobashi), no. 43 from the series One Hundred Views of Famous Places in Edo (Meisho edo hyakkei). Prints. Place: Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco, San Francisco, California, USA, Museum purchase, Achenbach Foundation for Graphic Arts Endowment Fund, 1981.1.58, http://www.thinker.org/.https://library.artstor.org/asset/AMICO_SAN_FRANCISCO_103857031.

Artist: Utagawa Hiroshige (Japanese, Tokyo (Edo) 1797-1858 Tokyo (Edo)). 1830s. 魚づくし 伊勢海老 芝蝦 / Ise-ebi and Shiba-ebi, from the series Uozukushi (Every Variety of Fish). Woodblock print, Prints. Place: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, https://www.metmuseum.org/. https://library.artstor.org/asset/SS7731421_7731421_11731500.

HIROSHIGE, Ando, Japanese, 1797-1858. 1840. A Shoal of Fishes series of 20. color woodcut. Place: Wetmore Print Collection, Art History Dept, Cummings Arts Center, Connecticut College, New London, Donated by Prof. Caroline Black, Botany Dept, Connecticut College. https://library.artstor.org/asset/CONNASIAN_106310616922.

IMAGE INFO

RESEARCH TEXTS

Grant, Patrick. “Geography’s Importance to Japan’s History.” Seattle: Education About Asia, Spring 1998. https://www.asianstudies.org/wp-content/uploads/geographys-importance-to-japans-history.pdf

Bishop, Carl Whiting. “The Historical Geography of Early Japan.” Geographical Review 13, no. 1 (1923): 40–63. https://doi.org/10.2307/208201.

Agency, Japan Meteorological. “General Information on Climate of Japan.” Japan Meteorological Agency | General Information on Climate of Japan. Accessed May 10, 2023. https://www.data.jma.go.jp/gmd/cpd/longfcst/en/tourist.html#:~:text=Eastern%20Japan%20has%20hot%20and,have%20a%20subtropical%20oceanic%20climate

Baner, Shantanu. “Fishing off Japan in the North-West Pacific: Geography.” Your Article Library, March 8, 2016. https://www.yourarticlelibrary.com/geography/fishing-off-japan-in-the-north-west-pacific-geography/77798

Bates, Heather. “Japanese Fish-Eating Culture and History.” WAGYUMAN, October 1, 2020. https://wagyuman.com/blogs/resources/japanese-fish-eating-culture-and-history

“Gyotaku.” Stormtree Studio. Accessed May 10, 2023. https://stormtreestudio.com/gyotaku/

Kakimoto, Noriyaki. Fishing Communities and the Geography of Fishery. Accessed May 10, 2023. https://www.jstage.jst.go.jp/article/grj1984b/60/2/60_2_203/_pdf.

Klein, Catharina. “Topic: Natural Disasters in Japan.” Statista, January 6, 2023. https://www.statista.com/topics/7363/natural-disasters-in-japan/#topicOverview

Kobayashi, Akira. “The Five Highways and Other Routes across Edo-Period Japan.” nippon.com, April 20, 2021. https://www.nippon.com/en/japan-topics/c08604/#.ZFwDr80mxvF.link.

SPECIAL THANKS TO HIROSHIGE.ORG