Background

Born in 1420 to an important Samurai family in the Bitchu Province of western Honshu, Sesshū came to be known as one of the greatest painters in Japanese history. He was raised as a Zen Buddhist, and at 11 years old he became a monk. While he was young, many people noticed how talented he was at art, and studied under other greats such as Tensho Shubun and Taikō Shojetsu. Sesshū’s popularity especially rose after he returned to Japan after a two year trip to China, where he got to know brilliant Chinese painters and became influenced by the impressive landscapes. Upon his return to Japan, he traveled around for a while until settling down in Oita. Here he established his own studio and worked for the Otomo family. During this time, Sesshū’s fandom grew even more, and he solidified his place in Japanese history.

Sesshū worked primarily in sumi-e, which literally means “painting in Chinese ink.” The ink for these paintings are made by burning pine twigs. The soot is then collected and mixed with resin. It is then formed into a flat stick, which can then be dipped in water and painted with. One of Sesshū’s most famous types of work is “Haboku-Sansui,” which is a scroll ink painting of a landscape. Sesshū only allowed himself to work with sumi-e ink, making most of his paintings all in shades of gray. What then becomes the most pronounced is his brush strokes, which vary in density and boldness. His works were also abstract, and white spaces and strokes were often left looking “unfinished.” With his own creativity and influences from his trip to China, Sesshū pioneered a style of painting that in itself became associated with “Japan-ness.” Today, Sesshū is incredibly revered, and his work has come to be known as quintessentially Japanese. This in itself explains “Japan-ness” even more. While Sesshū’s work includes influences from places other than Japan, this is what makes his art encompass “Japan-ness” even more because it reveals aspects of the historical and social climate at that time.

Summary

The images shown below display the wide variety of styles in which Sesshū Tōyō worked with. While using just sumi-e ink, Sesshū was able to create complex and thought-provoking paintings that when looked at closely, contain so much more than what the eye initially captures. Throughout all of Sessū’s works, his emotions are evident, and the viewer can see his commitment to the subject he cares about most, whether that be his faith, friends, or beautiful landscapes. Sesshū was a pioneer in ink painting, and created in ways that no one had done before. In using influences from China and adapting them to create his own unique styles, Sesshū redefined ink painting. Today, his work is instantly recognizable and revered. Every painting included below represents Sesshū’s influences and values, and shows just how thoughtful and passionate of an artist he really was.

Paintings

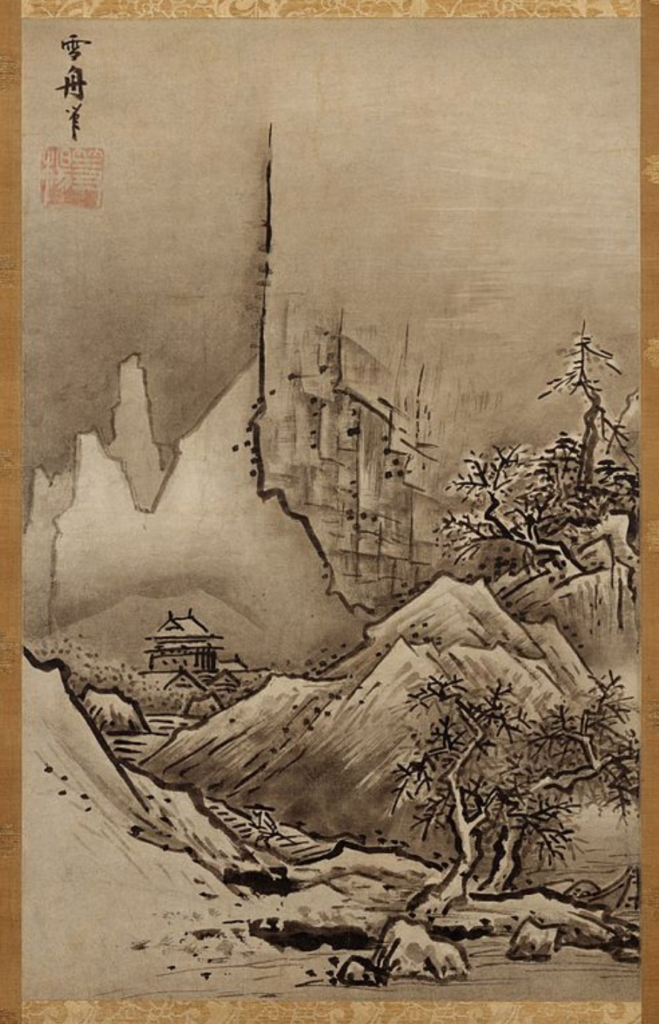

In the early years of his career, Sesshū primarily painted religious scenes as he was surrounded by Zen masters and patrons who supported his work. In the 1450s, Sesshū began to feel stuck and uninspired after spending years learning strictly Japanese techniques at home. He decided to broaden his horizons and travel to China. There, Sesshū was introduced to vast landscapes that differed greatly from the ones back home in his native Japan. Sesshū was greatly influenced by his trip to China, and this trip led him to create artwork that was totally unique and different compared to all of the other artwork done during the Muromachi period. Apart from being able to paint these vast landscapes, Sesshū challenged himself to exclusively paint with sumi-e ink. It is incredible to look at this painting in particular, and see the varying shades of gray that Sesshū was able to create with one black tone of ink. There is again a focus on depth in this painting, and the viewer can see as far back to the snowy peaks. There is also a house in the background, and as the viewer’s eyes reach the foreground, a small person appears. It can be seen that the foreground includes much heavier and darker brushstrokes while the background of the painting is made from light, wispy strokes. The sky appears to have a darker color, maybe made out of a wash from a combination of both water and ink. It appears as if a storm is looming and there is a heavy feeling in the air. Once again, Sesshū is able to incredibly portray an emotion or feeling from the use of a single medium.

This more abstract style of painting that Sesshū often did references back to the medium he uses, called literally “splashed ink.” Sesshū learned this technique through his travels in China, where this style of painting originated. It is said that this style actually came from artists being drunk and splattering ink with materials such as rags, brushes, or even hair. Sesshū was able to take this technique and make it his own, and soon after he adopted it, the style became popularized and moving forward can be seen in many other artist’s works. Sesshū followed a bit more of a regimented approach to this technique, and often he was depicting a landscape of some sort through his splashed ink pieces. It is interesting to compare this painting to Sesshū’s other styles of works. In his other works, there are extremely detailed features and brush strokes so intentional in size and weight. It is refreshing to see this side of Sesshū’s artwork, where he acts more freely with his brushstrokes and creates beautiful shapes and figures that can be traced to a background or can be accepted on their own for the non-obvious beauty within them. Still, the viewer can see slight details and nuances that make Sesshū’s work inherently Sesshū.

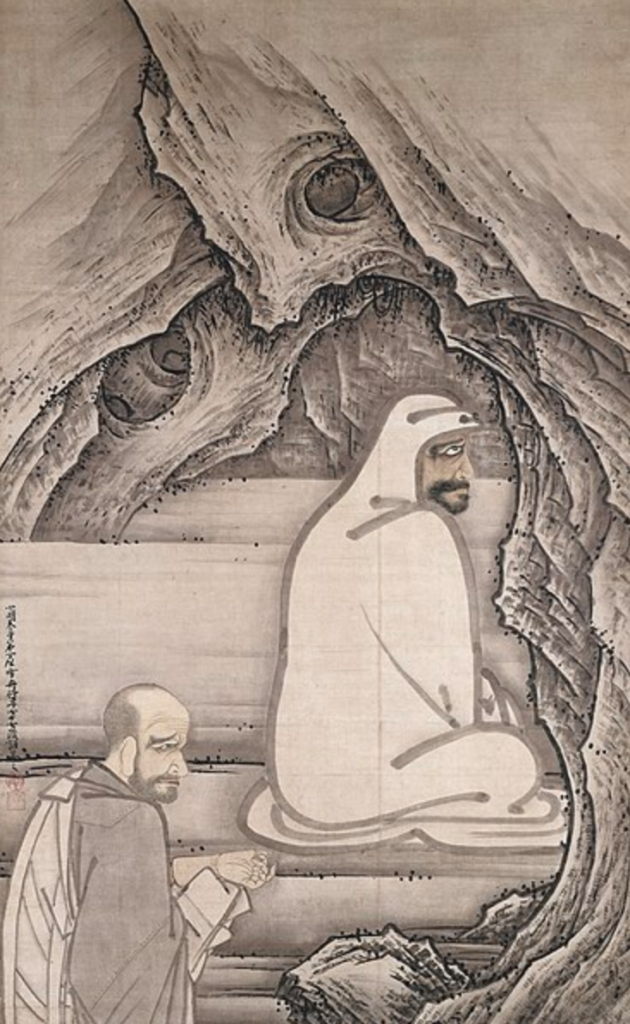

There is no doubt that Sesshū Tōyō’s work embodies Buddhism and contains an immense amount of Zen Buddhist references. From his background, it is known that Sesshū’s religion was incredibly important to him, so he often showed his devotion through his own artwork. In this particular painting Huike, a disciple of the founder of Zen Buddhism, Bodhidharma, is seen asking Bodhidharma if he can in fact be his disciple. To further prove his commitment, Huike cuts off his own left hand and offers it to Bodhidharma. What is especially interesting to notice in this painting is the varying line widths that Sesshū uses to illustrate this scene of extreme and complete devotion to one’s religion. The faces of Huike and Bodhidharma, as well as Huike’s cut off hand, stand out in this painting. They are so detailed and seem to be painted with the most delicate of brush strokes. The two men are also depicted in a much lighter tone than the rest of the painting. The rocks surrounding them appear to be very dark and bold, perhaps to represent some kind of metaphorical enclosure that faith provides. The expressions on both Huike and Bodhidharma’s faces seem intense and pensive, further displaying the intensity one feels towards their religion. It can be seen that this subject matter was incredibly important to Sesshū and played a large role in his life and throughout his artwork.

Ama-No-Hashidate is regarded by many as one of Sesshū’s most impressive pieces, and it is certainly one of his best known. After traveling throughout China and painting Chinese landscapes, Sesshū is now depicting his homeland of Japan. More specifically, this view includes Chionji Temple and the Seijoji Temples. In this marriage of both the religious and natural, two of Sesshū’s passions are displayed using small, minute brush strokes that show an astounding amount of detail. The depth in this painting is expansive and seems to go on forever, but the reason why this work is so fascinating is because of the particular view that is being depicted. It is unknown how Sesshū was able to travel to this extremely high point which allowed him to capture this incredible view. Some say that this view can only be captured from a helicopter, making Sesshū’s feat especially impressive. What is even more astonishing is that at this point, Sesshū was already in his 80s, so the fact that he was able to climb to this point in order to create this piece of artwork shows his dedication to his craft.

Later in his life, Sesshū began painting on scrolls and adding poetry to his work. On these scrolls were often Sesshū’s signature landscapes, and included with them would be poetry, either describing the scene being depicted with it on the scroll, talking about Zen Buddhism, or remembering loved ones who had passed away. In this particular image, Sesshū is remembering Bokushō Shūshō and Ryōan Keigo. Bokushō Shūshō was Sesshū’s close friend, and in the poem he is praising him. Ryōan Keigo was another well-known painter from the Muromachi period, and Sesshū is admiring and praising his work. The landscape shown in this painting is detailed and beautiful just like his other landscapes, and again Sesshū’s incredible brush strokes and attention to detail is shown. In including poetry with his work, the viewer can see Sesshū’s deep and personal connection to his paintings. Sesshū showed all of his emotions through his artwork, and this piece in particular referencing the people he admires most is a testament to Sesshū’s intentions and his works as a whole.

Bibliography

Isozaki, Arata. Japan-Ness in Architecture. Cambridge, Massachusetts: The MIT Press, 2011.

Japacul. “Sesshū’s Landscape Painting with Praise from Friends.” Masterpieces of Japanese Culture, 11 Feb. 2021, https://www.masterpiece-of-japanese-culture.com/paintings/sesshus-landscape-painting-with-praise-from-friends.

Lippit, Yukio. “Of Modes and Manners in Japanese Ink Painting: Sesshū’s ‘Splashed Ink Landscape’ of 1495.” The Art Bulletin, vol. 94, no. 1, 2012, pp. 50–77. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/23209211. Accessed 28 Apr. 2023.

Mittman, Dr. Asa Simon, and Dr. Asa Simon Mittman. “Nature: Spotlight – Sesshu Toyo’s Winter Landscape.” Smarthistory, https://smarthistory.org/theme-nature/.

“Sesshu Toyo – 11 Artworks – Painting.” Www.wikiart.org, https://www.wikiart.org/en/sesshu-toyo.

“Sesshū Tōyō.” 雪舟等楊 Sesshū Tōyō (1420-1506), https://terebess.hu/zen/mesterek/Sesshu.html.

Toyo, Sesshu. “Haboku Sansui, 1495 – Sesshu Toyo.” Www.wikiart.org, 1 Jan. 1495, https://www.wikiart.org/en/sesshu-toyo/haboku-sansui-1495.

“Works of Sesshu Toyo.” Masterpieces of Japanese Culture, 7 Dec. 2021, https://www.masterpiece-of-japanese-culture.com/works-of-sesshu-toyo.

-トーハク- 東京国立博物館. “National Treasure Gallery: Autumn and Winter Landscapes.” Tokyo National Museum, https://www.tnm.jp/modules/r_exhibition/index.php?controller=item&id=4271&lang=en.