The Zen gardens of the Muromachi period (1336-1573) in Japan are ones of beauty, peace, and tranquility. The creation of Zen gardens became more popular and common within the ruling class, monks and priests, and samurai warriors. have picked, are designed to be tranquil and peaceful spaces that encourage contemplation and meditation. Japanese gardens have their roots in the Shinto and Buddhism religions, which worshiped nature and its spirits. Balance, or sumi, is essential in the design principle of gardens, especially during the Muromachi period. Over time, these gardens evolved to become more than just a place of worship, they became an essential part of Japanese culture. I focused on gardens in Kyoto and those that were made during or around the Muromachi period, a time where religion and culture flourished. They are characterized by their use of natural materials like sand, stones, water, and vegetation, symbolism, and their ability to transport visitors to a world of harmony and contemplation.

Moss-covered stones, twisted tree trunks, and bumpy pathways are all valued for their unique character and the sense of history they bring to the garden. The use of these natural materials were arranged in patterns that were meant to create and mimic natural scenery such as rivers, islands, and mountains. Smooth sand, flowing water, and healthy vegetation are all celebrated for their beauty and significance. Gardens during the Muromachi period were often created within the grounds of temples, palaces, or the homes of the wealthy and were designed to be a place of peace, where someone could escape the hecticness of life. These gardens often have a pond or stream, with delicately placed rocks and bridges to create a sense of flow and movement. The use of rocks is particularly significant, as they are seen as symbols of strength and permanence. Japanese gardens are a place of beauty and peace where those who explore and view them can feel centered and harmonious.

Religion and Minimalism

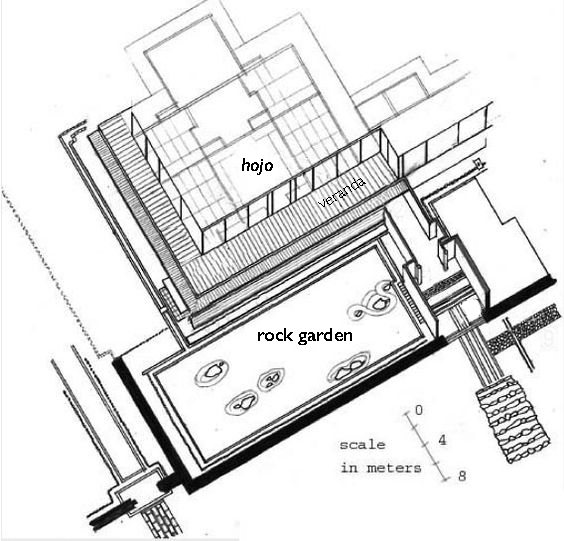

The amount of religious aspects of these gardens is significant. There was great cultural growth during the Muromachi period with the influence of Zen Buddhism. Zen Buddhism began in China as Chan Buddhism. Chan and Zen mean “meditation,” and it highlights the idea of self-reflection, peacefulness, and contemplation that all of these gardens strive to bring to those who visit. Instead of looking to deities, those who follow Zen Buddhism stress “the importance of the role of a teacher, with whom a disciple has a heart-mind connection,” (Asia Society). Zen Buddhism strived for minimalist and simplistic practices and Many temples built during this time had gardens built that attached to the temples to help promote meditation and religious advancement for those who lived there and for those who visited. The gardens during this period shifted to minimalist designs because the Buddhists were well-versed in the concept of minimalism as many Buddhist principles and practices resonated with it. One of the most important and significant shifts to minimalism in these gardens was the creation of Karesansui, or a dry garden. These dry gardens used nothing but sand, rocks, water, and gravel to represent simplicity and peace. These gardens were created to encourage inward thought and prayer for those who lived in the temples and for those who visited the temple and garden. One of the most famous and vistited examples of a karesansui garden is the Ryōanji Temple Rock Garden. It was created during the Muromachi period by Sōami. It is a single view-point sand and rock garden which is a type of Zen garden that is designed to be viewed from a single, fixed perspective which in this case, are the rocks in the center of the white gravel. This is a great example of a dry rock garden and a great example of how Zen Buddhism contributed to the creation of gardens during the Muromachi period. The single viewpoint also highlights the Zen principle of unity and our class principle of “Japan-ness.”

Many of these temples were built by monks, leaders, and warriors, Ashikaga Yoshimasa was one of them. Ashikaga Yoshimasa was a shogun during the Onin War that took place during the Muromachi period (1467-77). During this war, a lot of Kyoto was decimated and instead of continuing to fight, Ashikaga Yoshimasa left the war and built Gingkaku-ji and its beautiful garden. He turned it into a place of peace and contemplation instead of war and pain. He created the idea of simplicity which is showcased in this garden with its vegetation and delicate sand. He once said “I love my hut at the foot of the Moon Awaiting Mountain and the reflection of the sinking sky,” which truly displays what these gardens are for. Another significant creator is Soami, a Japanese artist alive during the Muromachi period. Some say that the Ryōanji rock garden because it was destroyed in the Onin War, Matsumoto, the son of the politician Hosokawa Katsumoto rebuilt it but others say it was rebuilt by Zen monk and artist, Sōami. Sōami is also known for the creation of the dry landscape garden (karesansui) of Daisen-in. The Daisen-in garden is part of a sub-temple of Daitoku-ji, a temple of the Rinzai school of Zen in Buddhism, (one of the five most important Zen temples of Kyoto). Making the connection of these gardens to Buddhism even stronger. The Daisen-in also has a connection to another style of art; painting. It was built between 1509 and 1513, some think by the temples founder, Kogaku Shuko. But others believe that Sōami is responsible for this garden as his fusuma landscape paintings are displayed inside the temple. This is also possible because of the fact that a lot of the gardens created during the Muromachi period were made in the tradition of Chinese paintings (which is where Zen Buddhism came from). Another garden that is attached to one of the five schools of Zen Buddhism is the Kenchōji garden created by the leader Hojo Tokiyori in 1253. The Kenchōji Temple and garden are the oldest Zen temple in Kamakura and it’s famous moss garden was created by the Zen master Muso Kokushi. Moss is viewed as a symbol of simplicity, humility, and perseverance, which are values that are highly valued in Japanese culture.

Traditionalism

There is also the aspect of traditionalism that is highlighted in these gardens. For the gardens created during the Muromachi period that were not dry gardens, moss was the main material. The moss gardens exemplify the traditionalism that these temples display and they have a long-standing tradition in Japan and are considered an important part of the country’s cultural heritage. Moss is also seen as a symbol of simplicity, humility, and perseverance, which are values that are highly valued in Japanese culture. A good example of a Zen garden that shows both minimalism and traditionalism is the Sōgenchi Garden of Tenryu Ji. This garden is full of beautiful moss, vegetation, and flowers (a classic garden design), water, and white gravel/sand (a Zen/minimalist style). The Sōgenchi Garden was created by Musō Soseki during the Muromachi period and and is a rock and moss garden. There are a number of lines in the sand which are there to show the connection of water to the Earth, showing the naturalism that these gardens are supposed to exhibit.

The Zen gardens of the Muromachi period are ones of great peace, beauty, and tranquility. They continue to be and will forever be appreciated and studied for years to come for their elegance, artistry, the idea of “Japan-ness” that they bring, and there profound philosophical and spiritual principles that came from Zen Buddhism. All of these gardens exhibit “Japan-ness” because of the traditional, religious, and philosophical ideals that they embody.

Bibliography

- Rock garden, Ryōanji, Kyoto, Japan (photo: Vincent Briccoli, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

- Kidder, J. Edward. The art of Japan. New York: Park Lane, 1985.

- Wybe Kuitert, Themes in the History of Japanese Garden Art (Honolulu: University of Hawai’i Press, 2002).

- “Ryōanji (Peaceful Dragon Temple) (Article).” Khan Academy, Khan Academy.

- Edward Kidder, The Art of Japan (Century, 1985)

- Bauer, Penny Kaela. “Daisen-In.” Traditional Kyoto.

- Kyoto Ginkaku-Ji Garten 2 – Wikimedia Commons. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Kyoto_Ginkaku-ji_Garten_2.jpg.

- Steinhardt, Nancy Shatzman. “Pavilion.” Grove Art Online

- “Types of Gardens.” n.d. Www.japan-Guide.com. Accessed May 2, 2023.

- “Rinzai-Obaku Zen | What Is Zen? – Basic Stance.” n.d. Zen.rinnou.net. Accessed May 2, 2023. http://zen.rinnou.net/whats_zen/index.html.

- Libretexts. 2021. “24.1: The Muromachi Period.” Humanities LibreTexts, March. https://human.libretexts.org/Bookshelves/Art/Art_History_(Boundless)/24%3A_Japan_After_1333_CE/24.01%3A_The_Muromachi_Period.

- German Vogel. 2010. “Kenchoji Japanese Garden – Kamakura, Japan.” Flickr. August 8, 2010. https://www.flickr.com/photos

- “Kenchoji Temple.” n.d. Www.japan-Guide.com. Accessed May 2, 2023. https://www.japan-guide.com/

- Ginkaku-ji | Traditional Kyoto. (n.d.). https://traditionalkyoto.com/gardens/ginkaku-ji/

- Real Japanese Gardens. n.d. “Ryōan-Ji.” https://japanesegardens.jp/tag/soami/.

- “Daitokuji Temple.” n.d. Kyoto Travel. https://www.japan-guide.com/e/e3910.html.

- “Story & Recommendation – Tenryu-Ji Temple in Arashiyama & Sagano(Temples & Shrines) | Sharing Kyoto.” n.d. Sharing Kyoto. https://sharing-kyoto.com/see_Tenryu-ji-Temple/story.