Exploring How the Japanese Dragon Became What It Now Is

The dragon is undoubtedly one of the most iconic and influential creatures in Japan’s extensive folklore. Almost every culture worldwide has something similar to a dragon, varying from the familiar Grimm beasts to more abstract or chimera entities. Yet, the fairytale dragon many Westerners grew up with and the Eastern serpentine dragon are the two most famous depictions.

The popularity of fantastic beasts and mystification for the cultures dubbed ‘oriental’ universalized Japanese dragons in the arts and literature. But where exactly did the dragon come from?

Historians understand very little about where and when dragons came from, but the creature came to Japan as a mash-up of Chinese, Korean, and Indigenous folklore. The earliest known references to Japanese dragons are Kojiki c. 680 AD and Nihongi c. 720 AD, which also happen to be the earliest recorded texts from Japan.

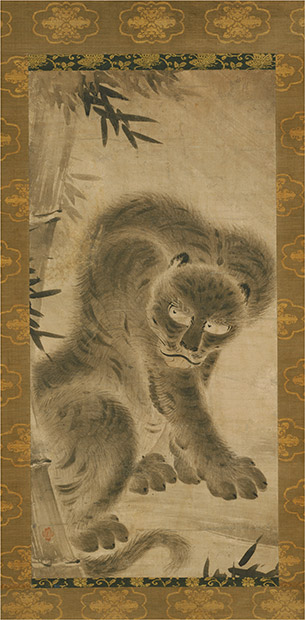

A 15th to early 16th-century set of two hanging scrolls illustrates China’s influence on Japanese depictions of dragons. Given that Taoism and other Chinese philosophies turned the tides of Asian folklore, the tiger and dragon are two of the most common subjects of zoomorphic art. However, focusing on the scroll with the dragon reveals that some earlier ones were more textured and almost soft in appearance. The eyes are more prominent and practically akin to modern cartoon art that enhances specific parts of a subject.

Now brings us to a very intriguing Japanese Dragon in the early 18th century. Made of iron and unpainted, this piece was created long after the scrolls but still radiates the same energy. Perhaps the iron gives a similar atmosphere to the calligraphy style, almost foreboding. The metallic sheen captures the intense value of the brewing storm from whence the dragon appears. While many modern dragons boast colorful scales, history sometimes prefers to appreciate the entity for its form alone. The medium of metal gives the appearance of whiskers, almost catlike structures from the brows and muzzle of the beast. What looked soft and almost like fur in the inked scrolls translated to spindles in the three-dimensional rendition, and this newer dragon has sharp structures down its spine.

Watatsumi, or Ryūjin, is one of many indigenous Japanese Dragons, a kami king of the sea and dragons. In his mythology, he secures jewels with oceanic properties capable of influencing tides in a palace–Ryūgū-jō–below the sea. This deity occupies works in both dragon and human forms. Among other works, he has been the subject of a woodblock print and a wooden statue.

Dragons and Kami are an integral part of Shintoism, the native religion of Japan, so a lot of the early imagery of dragons is tied to religion or Zen culture.

Interestingly, these two pieces have stunning color continuity and expressive vibrance despite being in different forms and media and created by other artists.

Japanese prints are incredibly popular for their paradoxical simplicity and intricacy. The color present is a stark contrast to the previous works, which is not necessarily crucial to the development of the dragon itself, but there are noticeable structural differences. For example, in the woodblock print, the dragon has a shorter snout and more excellent texture visible to the viewer.

In the late-19th century, the dragon continued to adorn household items such as porcelain dishwares. As usual, the dragon was a popular design choice, along with cranes and other animals.

Typically seen as a bringer of good fortune, it is no surprise that it gained the attention of Westerners looking for tokens to improve their luck. East-Asian dragons are a subject of fascination and are often used purely for aesthetics, regardless of meaning.

A recent piece of dragon art is a modern installation celebrating the Kenninji temple’s 800th anniversary. The dragons in this art are intended to mimic the earlier styles of depictions, especially with the expressive faces of the dragons. One of the dragons has an open mouth while the other has a closed mouth which interestingly is a motif likely borrowed from the Ryukyuan shisa; in Okinawa, the shisa is an entity usually depicted in pairs with a male and female. The male shisa has an open mouth to scare away evil, and the female holds its mouth closed to keep in good luck.

Most of the history of Japanese dragons is concentrated in the East-Asian region, but there is indisputable evidence of outside influence molding the legacy of the dragon. Asian arts have long been inspirational to the Western world, leading to imitation styles such as the chinoiserie, and the dragon has often been a subject of this. Art influenced by Asia cannot be considered ‘Asian art’ but rather ‘Asian inspired.’ These offer insight into how the rest of the world views their authentic counterparts but are only Asian in mimicry. There is no question if this art is ‘Asian,’ but an endless endeavor to explore every intricate detail that built up the creature as we see it now.

Animals in Japanese folklore. Accessed May 11, 2023. https://www.nga.gov/features/life-of-animals-in-japanese-art.html.

“The Art of Single Stroke Painting in Japan | National Geographic.” YouTube, July 13, 2018. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=g7H8IhGZnpM.

Ewer with Dragon. Photograph. New York City, n.d. Metropoliton Museum of Art.

Fuji Arts Japanese prints – recovering the stolen jewel from the Palace of the Dragon King by Kuniyoshi (1797 – 1861). Accessed May 11, 2023. https://www.fujiarts.com/cgi-bin/item.pl?item=741302.

House of the Dragon. “Japanese Dragon.” House of the Dragon. Accessed May 11, 2023. https://house-of-dragon.com/blogs/draconic-blog/japanese-dragon.

“Japanese Era Names and Japanese Imperial Calendar.” Suki Desu, June 7, 2017. https://skdesu.com/en/imperial-japanese-calendar/.

“Kennin-Ji.” Discover Kyoto. Accessed May 11, 2023. https://www.discoverkyoto.com/places-go/kennin-ji/.

McKelvie, Callum, and Benjamin Radford. “Dragons: A Brief History of the Mythical, Fire-Breathing Beasts.” LiveScience, January 18, 2022. https://www.livescience.com/25559-dragons.html.

Organization, Japan National Tourism. “Kenninji Temple: Travel Japan (Japan National Tourism Organization).” Travel Japan. Accessed May 11, 2023. https://www.japan.travel/en/spot/1182/.

“Religions – Shinto: Kami.” BBC, September 4, 2009. https://www.bbc.co.uk/religion/religions/shinto/beliefs/kami_1.shtml.

Ryūjin, Dragon King of the Sea. Photograph. New York City, n.d. The Metropoliton Museum of Art.