Overview

Kenzo Tange is one of Japan’s most influential and honored architects. Tange was born in Imabari, Shikoku Island, Japan in 1913. He studied in the Architecture Department of Tokoyo University, where he later became an assistant professor and organized the Tange Laboratory (Pritzker Prize). His influence on other architects comes from his designs and his career as a professor. Tange’s work strikes a unique balance between Modernism and traditional aesthetics. Additionally, he maintains a distinct sense of Japan-ness while being inspired by European architects, specifically the work of Le Corbusier, who inspired him to pursue a career in architecture. Looking at several examples of his most notable work, we see how his designs are of the moment, cultural, and political. The three projects I have selected are; Hiroshima Peace Memorial Park, his first major commission, Tokyo Bay Proposal, and the National Olympic Gymnasium. I chose these projects because they have important cultural significance and represent important moments in Tange’s career.

Hiroshima Peace Memorial Park

On Monday, August 6, 1945, American B-29 Bomber “Enola Gay” released a nuclear bomb nicknamed “Little Boy” onto the city of Hiroshima; “The bomb vaporized people half a mile away from ground zero. Bronze statues melted, roof tiles fused together, and the exposed skin of people miles away burned from the intense infrared energy unleashed. At least 80,000 people died instantly.” (Bamford, 2020) Kenzo Tange received the commission for replanning the city of Hiroshima; his design is hugely symbolic, meant to express the solidarity of humankind and commitment to peace (Fracalossi, 2011).

The first image shows the main building, the Peace Memorial Museum, which holds exhibition and memorial halls. The Peace Memorial Museum is an excellent example of Le Corbusier’s influence on Tange’s designs. Le Corbusier is known for developing five points of architectural design principles; Pilotis (pillars), roof garden, open floor plan, long windows, and open facades (“Le Corbusier”). Looking at the Peace Hall, Tange incorporated these principles; the most apparent reference to these principles is the fact that the museum is built on top of pillars, or pilotis. In addition, although Le Corbusier is most known for long horizontal windows, Tange using a facade of windows can also be interpreted as a nod to Corbusier’s designs. However, the windows not only reference Corbusier; Tange’s sunshade element and modular facade arrangement align with traditional Japanese designs (Fracalossi, 2011). Additionally, the symmetry of the building is a nod to Japanese design elements.There is also political significance to Tange receiving the commission for this project. Tange taking inspiration from Le Corbusier is important in this regard because Corbusier is a Swiss-French architect, so choosing a design with Swiss-French inspiration rather than one inspired by German design signifies the government’s desire to distance a newly democratic Japan from the negative association of the war-time Axis Alliance, which included Japan, Germany, and Italy. (Steele, 2017, 76-77).

Figure 1: Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum, Hiroshima, Japan, Designed by Kenzo Tange, Built 1955

Moving away from the main building, the second image shows the Peace Monument. The arch-shaped sculpture, made of concrete like the museum, has a hyperbolic parabola structure that resembles a traditional Haniwa tomb (Glancey, 2005). The parabolic shape can also be linked to other Japanese artifacts, including ancient curved beads called magatama and bronze ceremonial bells called d taku (Cho, 2012). The combination of modernist design elements, for example, the use of concrete and references to traditional Japanese design elements and artifacts, expresses forward thinking with an appreciation for the past, which connects to a quote from Kenzo Tange where he expresses his belief that tradition serves as a catalyst in creativity (Pritzker Prize).

Tokyo Bay Proposal

Kenzo Tange’s 1960 plan for redesigning Tokyo aimed to address overpopulation and challenges with urban sprawl. This proposal is different from the other projects mentioned for a couple of reasons; first, it was never realized, so it is a conceptual project; second, the motivation for this proposal was to solve a social problem. Tange is quoted as, “I feel however, that we architects have a special duty and mission… (to contribute) to the socio-cultural development of architecture and urban planning.” (ArchEyes Team, 2020) This means Tange was not designing purely for the sake of form and creativity but also to provide solutions.

Looking at the first picture, you see a system of bridges and highways that form a chain and extend across the bay with strips that expand out from the chain. From the top view, the organization of the city expansion is similar to a spine, which ties into the Metabolism architecture movement that started in Japan. Architects Kiyonori Kikutake, Masato Otaka, Fumihiko Maki, Noriaki Kurokawa, and architectural critic Noboru Kawazoe formed the group of “Metabolists,” to whom Tange is credited as a mentor (Lin, 2007). In a statement from the Metabolism pamphlet, they explain that they “regard human society as a vital process, a continuous development from atom to nebula. The reason why we use the biological word metabolism is that we believe design and technology should denote human vitality.” (Lin, 2007) Considering the Metabolist perspective of cities as organic and evolving processes, the spine-like organization of Tange’s proposal is symbolic of these ideals.

As you can see in the second image of Tange’s model, the strips that expand out from the chain have smaller, A-shaped residential structures, while the structures within the chain are much taller. The smaller buildings’ sloped shape resembles a traditional Japanese gable roof, while the taller structures have a more modernist form. Furthering the idea of cities being organic processes is the idea of infrastructure having life cycles; within Tange’s design, the larger chain system was meant to have a longer life cycle and connect to the individual residential structures that were meant to have shorter life cycles based on changing needs of the population (Lin, 2007).

National Olympic Gymnasium

Lastly, we will look at Tange’s National Olympic Gymnasium, which he designed for the 1964 Summer Olympics in Tokyo, Japan. The National Olympic Gymnasium is an incredibly important project for Tange’s career because it is one of the selected works that earned him the Pritzker Prize in 1987, one of the most prestigious awards an architect can receive. Tange was selected as the winner of more than five-hundred nominees and was also the first Japanese architect to receive the award, making the award all the more groundbreaking (Forgey, 1987).

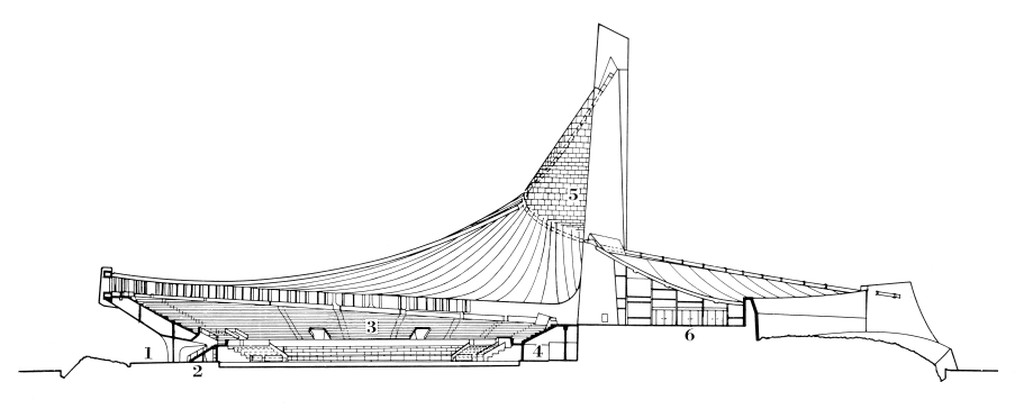

As seen in the first image, Tange’s design has an impressive and dramatic curving form. To accomplish this, Tange used a suspension roof structure that relied on wire ropes to suspend the roof; this was the first time this technology had been used (ArchEyes Team, 2020)—this use of innovative technology and use of concrete shows Tange’s forward-thinking and appreciation for modernist aesthetics. In addition, when designing the gymnasium, Tange considered the site of the building. As a result, the sweeping profile of the building creates the effect that it is emerging from the site (ArchEyes Team, 2020). Finally, although the references to traditional Japanese architecture on the design’s exterior are somewhat abstract, the shape of the building loosely resembles the shapes seen in Japanese Pagodas.

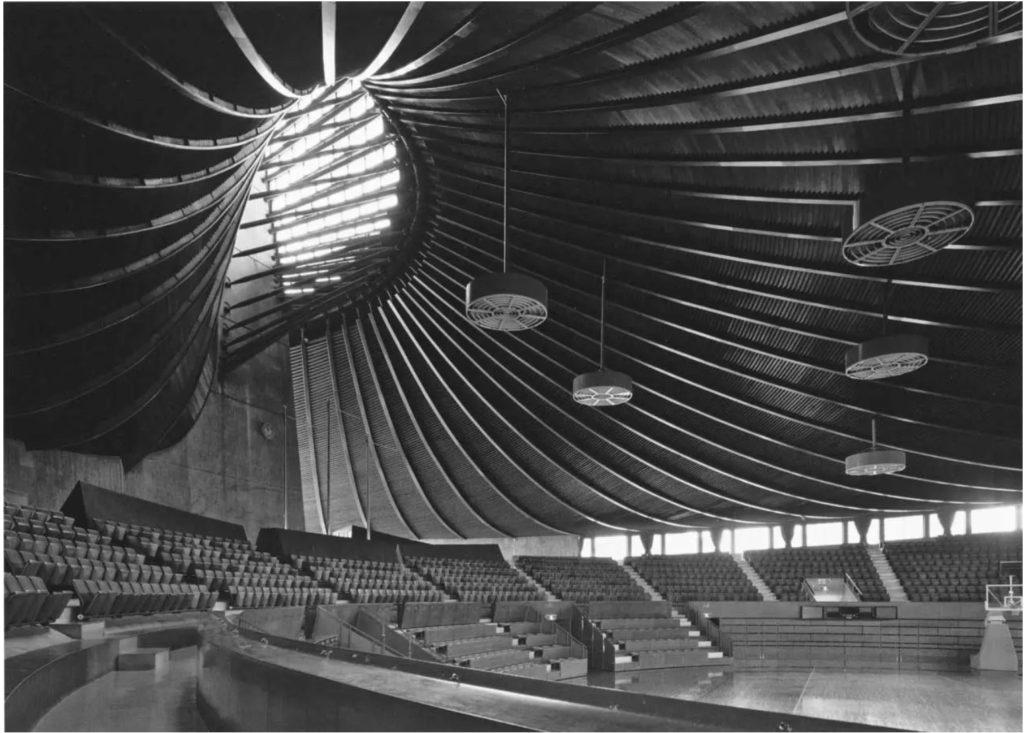

Designing the interior of the gymnasium posed a challenge; Tange said, “The biggest problem, with respect to the interior space, was guaranteeing that it not take on inhuman proportions when empty or filled with just a few people. We wanted to create and maintain a unified environment where athletes and spectators share growing mutual emotion. A single space—not closed and oppressive but free and open—a space in which the fifteen thousand spectators can also move and flow ‘gently’ in functional and psychological terms.” (ArchEyes Team, 2020). While the interior of the gymnasium is quite large, the organic and curved shape of the ceiling makes the open space feel less vast. Additionally, the interior considers traditional elements of Japanese interior design. The skylight allows natural light, a classic element of Japanese design, to be filtered into the gymnasium, creating a warm feeling. While the photograph is in black and white, Tange used a minimalist and natural color palette for the interior of the gymnasium, as seen in traditional Japanese interiors.

Conclusion

The designs by Kenzo Tange have a unique sense of Japan-ness. Looking at Tange’s projects, there is clear inspiration from the work of Le Corbusier, leading to him using materials like concrete and modernist features that are not seen in traditional Japanese architecture. However, many of his structural forms take inspiration from traditional designs, like pagodas, gable roofs, and Haniwa tombs. He was also largely influential in architectural movements that originated in Japan, like Metabolism, which expresses Japan-ness in a non-traditional way. His balance of references to the past, and forward-thinking resulted in the creation of timeless works that inspired the following generations of architects in Japan and beyond.

Bibliography

ArchEyes Team. “Kenzo Tange’s Vision for Tokyo in 1960: A Master Plan.” ArchEyes, October 9, 2022. https://archeyes.com/plan-tokyo-1960-kenzo-tange/.

ArchEyes Team. “National Gymnasium for Tokyo Olympics 1964 / Kenzo Tange.” ArchEyes, December 11, 2020. https://archeyes.com/national-gymnasium-for-tokyo-olympics-kenzo-tange/.

Bamford, Tyler. “The Most Fearsome Sight: The Atomic Bombing of Hiroshima: The National WWII Museum: New Orleans.” The National WWII Museum | New Orleans, August 6, 2020. https://www.nationalww2museum.org/war/articles/atomic-bomb-hiroshima.

Cho, Hyunjung. “Hiroshima Peace Memorial Park and the Making of Japanese Postwar Architecture.” Journal of Architectural Education 66, no. 1 (2012): 72–83. https://doi.org/10.1080/10464883.2012.720915.

Forgey, Benjamin. “Kenzo Tange Wins Pritzker.” The Washington Post, March 19, 1987. https://www.washingtonpost.com/archive/lifestyle/1987/03/19/kenzo-tange-wins-pritzker/d7269751-d227-4cb0-a973-e009f5f03d4b/.

Fracalossi, Igor. “Ad Classics: Hiroshima Peace Center and Memorial Park / Kenzo Tange.” ArchDaily, August 29, 2011. https://www.archdaily.com/160170/ad-classics-hiroshima-peace-center-and-memorial-park-kenzo-tange.

Glancey, Jonathan. “Obituary: Kenzo Tange.” The Guardian, March 23, 2005. https://www.theguardian.com/news/2005/mar/23/guardianobituaries.artsobituaries1.

“Le Corbusier – Architect, Designer, Artist, Pioneer and a Unique Personality.” Le Corbusier – architect, designer, artist, pioneer and a unique personality. Accessed May 7, 2023. https://www.lescouleurs.ch/en/the-colours/le-corbusier#:~:text=In%20the%20course%20of%20his,long%20windows%20and%20open%20facades.

Lin, Zhongjie. “URBAN STRUCTURE FOR THE EXPANDING METROPOLIS: KENZO TANGE’S 1960 PLAN FOR TOKYO.” Journal of Architectural and Planning Research 24, no. 2 (2007): 109–24. http://www.jstor.org/stable/43030795.

Steele, James. “Post-War Reconstruction, from Survival to Recovery: 1945–1950.” Essay. In Contemporary Japanese Architecture: Tracing the Next Generation. New York: Routledge, 2017.