By: Althea Beattie

Overview:

During his 16-year pilgrimage to India, Chinese monk Hsüan-tsang crafted detailed accounts of the Bamiyan Valley in Afghanistan. He described the two colossal Buddha statues as well as various caves, niches, and other statues located in the valley. Through examining his accounts, we can recognize a pattern of Buddhist iconography in the valley. The giant statues themselves are representations of the Buddha as an icon, or a widely recognized symbol. The niches of the Giant Buddhas and the various caves across the valley are decorated with wall paintings depicting Buddhist imagery and Buddha icons. Furthermore, much of the art in the valley has fallen victim to iconoclasm, which is the destruction of icons. Through my studies of the Bamiyan Valley, I have recognized that the asian art located in the area can teach us a lot about the concepts of icons, iconography, and iconoclasm.

Buddhism was introduced to the Bamiyan Valley in Afghanistan during the early Kushan Period. The Kushan empire flourished from the 1st to the 5th centuries A.D. and adopted elements of Hellenistic and Buddhist cultures. The prosperity of the Kushan empire led to a melting pot of cultural and religious traditions in Central Asia and enabled Bamiyan’s status as a major cultural center. In Benjamin Rowland’s book, The Art of Central Asia, he noted that “the most important center of Buddhism and its art in Afghan Turkestan was at Bāmiyān” (82). The Giant Buddhas in Bamiyan were erected just after the Kushan period and contain artwork in their niches that display elements of Buddhism from India. This Buddhist iconography is present in this location because of the spread of culture across Central Asia during the Kushan Period. It is important to note that “Bamiyan was never an important center of political power, but served as a ceremonial and spiritual center that attracted and comforted crowds of pilgrims and merchants traveling between Central and South Asia” (Klimburg-Salter, 10). Furthermore, “[t]he proximity of the city and the royal palace to the Buddhist complex, along with the rituals performed there by the king, indicates that the Bamiyan Valley was the religious, as well as the political and commercial, center of the Hindu Kush”, which is the mountain range in which the Bamiyan valley is located (Klimburg-Salter, 72).

In Buddhism, there is an idea that the Buddha is a cosmic being, which is displayed in the belief that the Buddha is the generative force at the center of the universe and all phenomena emanate from it. As a cosmic being, the Buddha has supernatural abilities that are reflected in the Giant Buddhas’ protection of the Bamiyan Valley. Since the valley is located along the Silk Road, the Giant Buddhas were thought to protect merchants who traveled through it. The Bamiyan Valley was able to become such a cultural sanctuary because of the Buddhist ideals that are reflected in the iconographic art.

The goal of this chapter is to examine the iconography of Buddhas in the Bamiyan Valley in Afghanistan in order to give readers a better understanding of the terms icons and iconoclasm. Furthermore, I will examine how the Buddha iconography in the Bamiyan Valley reflects its status as a major Buddhist cultural center in Central Asia. I will also discuss how the concept of the Buddha as a cosmic being is present in the valley’s art. The following images were chosen because together they demonstrate the concepts of icon, iconography, and iconoclasm, and reflect Bamiyan’s status as a Buddhist cultural center as well as represent the Buddha as a cosmic being.

Terms to Know:

- Icon: A widely recognized symbol that appears across art forms. Icons have specific repeatable features that allow them to be identified.

- Iconography: The identification and interpretation of an icon.

- Iconoclasm: The destruction of and hostility toward icons.

- Idolatry: The worship of idols (images or representations of gods).

- Buddha: Icons are usually religious symbols or figures, so the Buddha is a well known Icon. A Buddha can be identified by its specific features that include it’s monk’s robes, frontality, halo, physiognomy (facial features) and mudra (symbolic hand gestures).

- Context of Bamiyan: The Buddha icon is present throughout the Bamiyan valley which reflects its status as a Buddhist center.

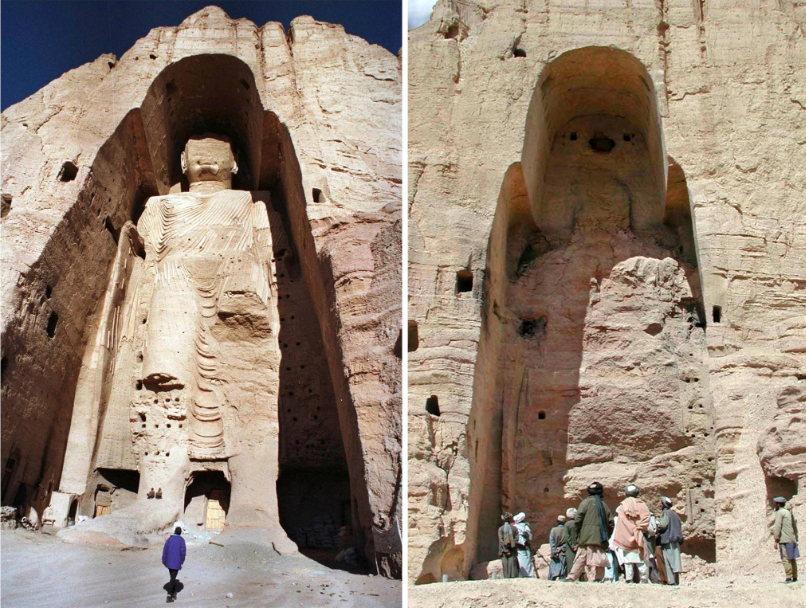

Description: This image depicts the West Giant Buddha located in the Bamiyan Valley. The Buddha itself is an icon which can be identified in this image by its frontality and monks robes. If the Giant Buddha was still intact in this image, its icon status could also be recognized by its physiognomy, or facial features, and mudra, or symbolic hand gestures. In her book, The Kingdom of Bamiyan: Buddhist art and culture of the Hindu Kush, Dr. Deborah Klimburg-Salter noted that “It is possible that the right hand was in abhayamudra (the gesture of fearlessness), and the left in varadamudra (the gesture of charity)” (88). The charitable and fearless hand gestures performed by the Giant Buddha represent the fact that it is meant to protect travelers in the valley. Furthermore, the extreme size of the West Giant Buddha implies the Buddhist Mahāyāna ideal that the Buddha is a cosmic being. The Buddha’s intrinsic quality of size represents its all-powerful cosmic abilities and its supernatural nature that allow it to protect travelers on the silk road and the Bamiyan Valley in general. Benjamin Rowland explains that “the purpose of such a gigantic image…was to indicate the more than mortal stature of the personage portrayed; in this case, to present the Buddha as a veritable Mahāpurusa, or embodiment of the cosmos” (85).

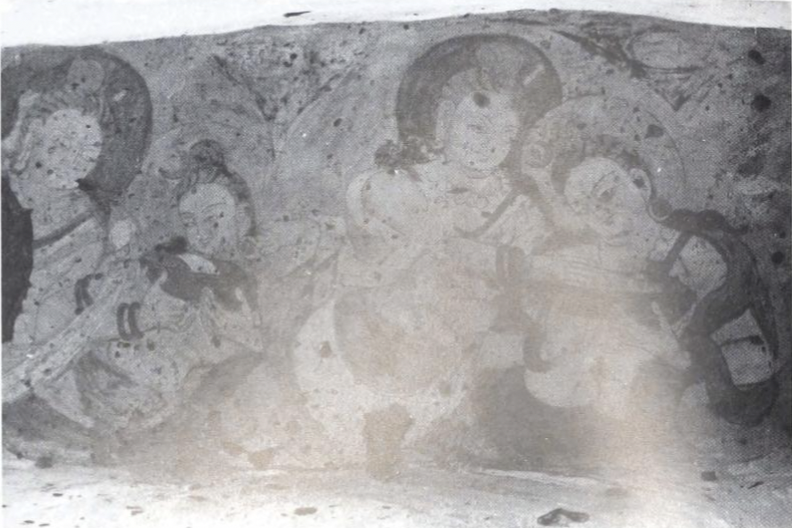

Description: This image is another representation of the Buddha as an embodiment of greater cosmic forces. In Buddhism, the Cosmic Buddha is the generative force from which the universe emanates. In this case, the Sun-god is an extension of the Buddha and is a representation of the Buddha’s cosmic force, since the Sun is at the center of our solar system. This painting is a “symbolical reference to the solar character of the Buddha” (Rowland 86). The architectural context is important in this instance of Buddha iconography because it further represents the Buddha as a cosmic force. This painting is located at the soffit of the niche of the East Giant Buddha, so viewers are forced to look up at the Sun-God, reminding them of its status in as a higher-being in the cosmos. Additionally, this painting represents the idea that Bamiyan is a melting pot of cultures because it displays a “syncretic combination of Iranian and Indian elements, both stylistic and iconographic” (Rowland 88).

Description: This painting shows four Buddha icons, which can be identified by their halos, physiognomy, and monks robes. This painting is located in Niche H in the Bamiyan valley, which is “about halfway between the two colossal standing Buddhas” (Klimburg-Salter, 164). Along with its wall paintings, Niche H contains a large, stone, seated Buddha figure. Again, the architectural context is important because it is located on the soffit of the niche, meaning it is above the seated Buddha figure. Because of this, viewers are forced to look up at the image as a reminder of the Buddhas’ cosmic status.

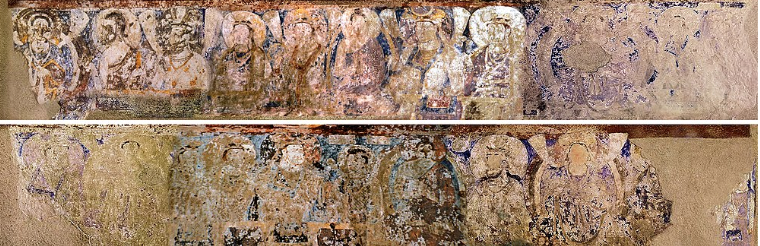

Description: This image is an example of iconoclasm, which is the act of destroying religious icons. In this image, we see the Buddha on the left and its two donors on the right. The Buddha and donors have had their faces scratched off as an act of early iconoclasm. This painting also reflects Bamiyan’s status as a major cultural center because it depicts donors from Central Asia who are wearing Iranian and Persian garments. This piece combines elements of classical art such as repetition and movement, elements of the Iranian world in the garments, and elements from India in the Buddha icons. This is evidence that Bamiyan is a “roundabout for the reception and diffusion of art forms from the classical, Iranian, and Indian worlds” (Rowland 82).

Description: This image is a depiction of the West Giant Buddha before and after it’s destruction. This more recent iconoclasm was performed by the Taliban in March of 2001 when “Mullah Muhammad Omar, the leader of the Taliban, issued a decree ordering the elimination of all non-Islamic statues and sanctuaries in Afghanistan” (Centlivres). The Mullah justified this iconoclasm by saying “‘If the statues were objects of cult for an Afghan minority, we would have to respect their belief and its objects, but we don’t have a single Buddhist in Afghanistan,’ said the Mullah, ‘so why preserve false [sic] idols?’” (Centlivres). This quote brings up an important question of whether or not the status of an icon is tied to it’s political, social, and architectural surroundings.

What is Asian Art?

While Asian Art is expansive and includes pieces, styles, and imagery from many cultures and countries, the artwork of the Bamiyan Valley exemplifies Asian Art as a whole. The styles of the various art forms representing Buddhist iconographies including the Buddha statues and wall paintings display influences from India and Central Asia. The paintings Buddha and Donors and A Sun-god in his Chariot both combine elements from multiple Asian countries such as Iran, India, and Afghanistan. Furthermore, the presence of the Silk Road in Bamiyan brought various ideas, traditions, and products from all around Asia into the valley. Additionally, since Buddhism is generally concentrated in South East Asia, the dominance of the religion and culture influenced the art that was present in the Bamiyan Valley, making it inherently Asian. In sum, Asian Art can be characterized by the historical, architectural, and geographical context of the works, as well as the Asian influences that can be identified in their combination of cultural and religious symbolism and styles.

Bibliography

Texts:

Benjamin Rowland, The Art of Central Asia, New York: Crown, 1974. https://moodle.conncoll.edu/pluginfile.php/406418/mod_resource/content/2/Rowland%20central%20asia%205%20Bamiyan.pdf

Dr. Deborah Klimburg-Salter, The Kingdom of Bāmiyān: Buddhist art and culture of the Hindu Kush, Naples, Rome, 1989. https://archive.org/details/dli.pahar.3623/page/n1/mode/2up?view=theater

Pierre Centlivres, The Death of the Buddhas of Bamiyan, Middle East Institute., April 18, 2012. https://www.mei.edu/publications/death-buddhas-bamiyan

Sources:

UNESCO, Silk Roads Programme. https://en.unesco.org/silkroad/content/bamiyan

Smithsonian. https://asia.si.edu/research/cosmic-buddha/

Images:

West Giant Buddha, 175 ft tall, stone, late 6th – early 7th centuries A.D., Bamiyan Province, Afghanistan, Afghanistani, Artstor, https://library.artstor.org/#/asset/ACSAA_MICHIGAN_1039425966;prevRouteTS=1678220284421;groupId=f690fc66-01e7-4822-b4b4-f7f48cb60f65, The American Council for Southern Asian Art (ACSAA), http://www.umich.edu/~hartspc/acsaa/index.html.

A Sun-god in his Chariot, wall painting on the soffit of the niche of the 35 m. Buddha (East Giant Buddha), 6th – 7th century A.D., Bamiyan, Afghanistan, Buddhist, Benjamin Rowland, The Art of Central Asia (New York, 1974), https://moodle.conncoll.edu/pluginfile.php/406418/mod_resource/content/2/Rowland%20central%20asia%205%20Bamiyan.pdf.

Painting in cusp of soffit of the niche, 6th-7th centuries A.D., Niche H, Bamiyan, Afghanistan, Buddhist, Deborah Klimburg-Salter, The Kingdom of Bamiyan, Buddhist Art and Culture of the Hindu Kush (Naples, Rome, 1989), https://archive.org/details/dli.pahar.3623/page/n1/mode/2up?view=theater.

Buddha and Donors, east wall at the summit of the niche of the 35 m. Buddha (East Giant Buddha), 6th -7th century A.D., Bamiyan, Afghanistan, Buddhist, Benjamin Rowland, The Art of Central Asia (New York, 1974), https://moodle.conncoll.edu/pluginfile.php/406418/mod_resource/content/2/Rowland%20central%20asia%205%20Bamiyan.pdf.

A combination photo of the 180-foot-high Buddha statue in Bamiyan, central Afghanistan on Dec. 18, 1997, left, and after its destruction on March 26, 2001. (Muzammil Pasha, Sayed Salahuddin/Reuters), The Washington Post, https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/worldviews/wp/2015/07/30/what-mullah-omar-took-from-afghanistan-that-can-never-be-returned/.