Overview

The mandala is a very popular form of art and has taken on many different meanings. Some of the most common definitions of the mandala include; “an organized structure that is organized around a central unifying principle, (within tantric practices) the sacred environment and dwelling place of a central deity, surrounded by a retinue of subordinates which is visualized by the practitioner, and a representation of the celestial realm. (Chris, Encyclopedia Britannica) Mandala is also commonly used as a catch-all term referring to paintings, diagrams, or architectural structures with a particular symbolic meaning. (Van Gordon)

The architecture of the mandala consists of three main characteristics; a double symmetric structure, a circle as the center, and the depiction of the lotus flower (typical). The lotus flower motif as well as the use of circles were meant to represent the expression of an idea that emerges in all directions. Commonly with mandalas, this “idea” was Buddhism and the spread it was depicting was the spread of Buddhist doctrine throughout Asia. Nowadays when you look at a mandala it is common to observe damage of some sort, whether minute in best-case scenarios or quite significant in worst (but most common) scenarios. This damage is most likely caused by the action of rolling or folding the mandala (and even in some cases cutting the mandala into pieces) to transport it. The mandala is a common icon in Asian art and there are quite a few elements of mandalas that make them easy to identify. Some of these elements include the depiction of squares and circles, four directions and gates, cosmic buddhas, Bodhivisattvas, offerings, and gatekeepers. All of these signify the importance of the mandala as a representation of the universe in its most ideal form as well as the celestial realm of the Gods.

The Goal of the Chapter

The goal of this chapter is to analyze and draw similarities among different examples of mandalas from across Asia and to gain an understanding of the many forms in which the mandala can be represented/used.

Author’s Background & Personal Interest

The mandala is one of the most popular icons of Asian Art and its consistency makes it easy for even the non-professional to identify. The mandala became popular in modern culture with the rise of yoga and Zen. Mandalas in today’s culture, particularly in the West are typically depicted in yoga studios and backyard gardens. This being my first experience with the mandala, I wanted to dive into the true origins of the mandala and through doing so I found that the mandala can take on many forms, intriguing me further and eventually inspiring this chapter.

Questions & Issues That Inspired the Work

The main questions that drove my research for writing this chapter were, what is the mandala? What can it/does it stand for in varying places? And, how does the representation of the mandala impact its meaning to the people/culture who created it? I believe that these questions best encompass not only the prominence of the mandala across Asia but also, and arguably more importantly, the permanence of the mandala even into modern times and its applicability to modern life no matter how different current culture may compare to that of the culture that existed hundreds if not thousands of years ago when these pieces were created.

Broader Humanistic Issues & Concerns

One of the biggest issues Asian art historians face is that so few examples (compared to their European counterparts) are left standing. This is due to a variety of circumstances such as war, conflict, natural disaster, and limited interest just to name a few. Because of the lack of original pieces, however, understanding of the cultures and the people that created them becomes limited. Part of the goal of this chapter is to increase understanding and awareness of these cultures and peoples to create a sense of appreciation and drive to preserve these pieces and thus their cultures for future generations.

Visual Materials

Why?

After searching through a variety of sources and discovering innumerable examples of varying mandalas that I could use, I ultimately chose the pieces that are discussed in this chapter because I felt that they best represented the main configurations of the mandala as well as a wide variety of cultures and uses for the mandala. I feel that these examples best act as pillars of their artistic type that once understood, the reader can apply the knowledge they learn in this chapter to other similar pieces they encounter out in the world.

These pieces should be regarded as collected and compared and contrasted because they each are intrinsically a mandala, despite how much everything else varies. This being said, these pieces are a perfect collection of pieces that both share great similarities while also being drastically different, best proving my case of the many forms of the mandala.

Visual Analysis

Both ceiling mandalas exhibit common characteristics of a mandala, including the depiction of squares and circles which in this case can be seen in Figure 1 as a circular center surrounded by a square-shaped perimeter, which is turned slighting to give the impression of a rhombus. Figure 2 does not display a circular motif yet it still conveys the same energy through the use of squares to create concentric-esque layers, starting small at the center and increasing in size as one’s gaze approaches the perimeter.

The skylight (figure 2) is modeled after a lantern ceiling typically seen in Bamiyan and India. Most likely crafted inside buildings of religious significance, this connection provides an association with these recreations and the sacred space. Mandalas are very frequently associated with sacred space and divine powers as it (as mentioned above) is typically used to represent the spiritual/celestial realm. In this instance, light is being let in by the glass in the center of the mandala, not only further emphasizing the mid-point of the piece but also creating a semi-spotlight on the viewer who stands under the light it lets in. In contrast, figure 1 is constructed to mute the light in the center and instead darkest in the middle while the light permeates outwards towards the perimeter.

Unlike the previous pieces shown, Figure 3 is a mandapa. A mandapa according to Encyclopedia Britannica is a pillared hall or pavilion used for public rituals in Indian architecture, especially observed in Hindu temple architecture. Mandapas are described as “open” or “closed” depending on whether they have walls. Figure 3 is extravagantly decorated and its level of detail is so ornate that when one looks up at it it is impossible not to be in awe of the craftsmanship that went into its creation and its subsequent preservation. This mandala, like the other two pieces seen at the Metropolitan Museum, is also a ceiling mandala. Its intricate detailing is also a common element of the mandala motif. Mandalas as can be seen from the earlier examples can be both highly detailed and quite simple. Typically mandalas, particularly painted mandalas which will be discussed later in this chapter, tend to be more detailed. According to the plaque next to this piece at the Metropolitan Museum of Art where this structure is now located, this piece originally belonged to the “gudha-mandapa” (also known as a meeting and prayer hall) of the Vadi Parashvana Jain temple in Patan, Gujarat. (MET). This piece was discarded during the renovation and enlargement of the temple back in the 1900s. The piece was originally painted as traces of pigment indicate. The location of this piece originally is unknown however it is stipulated that it was once on top of a flat roof and allowed sunlight into the interior of the structure. What is displayed in the MET was not the entirety of the structure as some of the piece was left out (specifically one of the four sides) to allow for easier viewing of the piece by visitors to the museum. (MET)

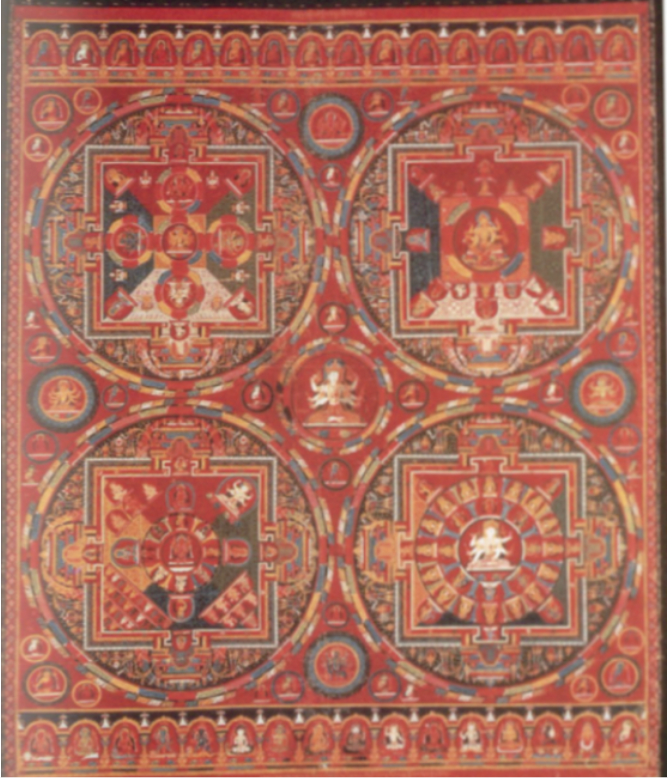

Figure 4 is really interesting because unlike the other pieces included in this chapter, it does not center around one large mid-point. Instead, the middle circle is small and it is easy to look over it as the eye gazes at the four circles in each of the four corners of the piece. Each of the four circles can be considered in and of themselves individual mandalas all included within one larger mandala. Each circle as well as the greater piece as a whole includes a center point with a surrounding motif that extends from it. The colors of this piece are extremely vivid, the reds, blues, and greens all create warmth as well as convey a deeper meaning. This type of painting is a style originating from the Sakaypa monastery of Ngor and is associated with tangkas dating from the mid-14th-early 15th centuries, each of which are also composed of four separate mandalas.

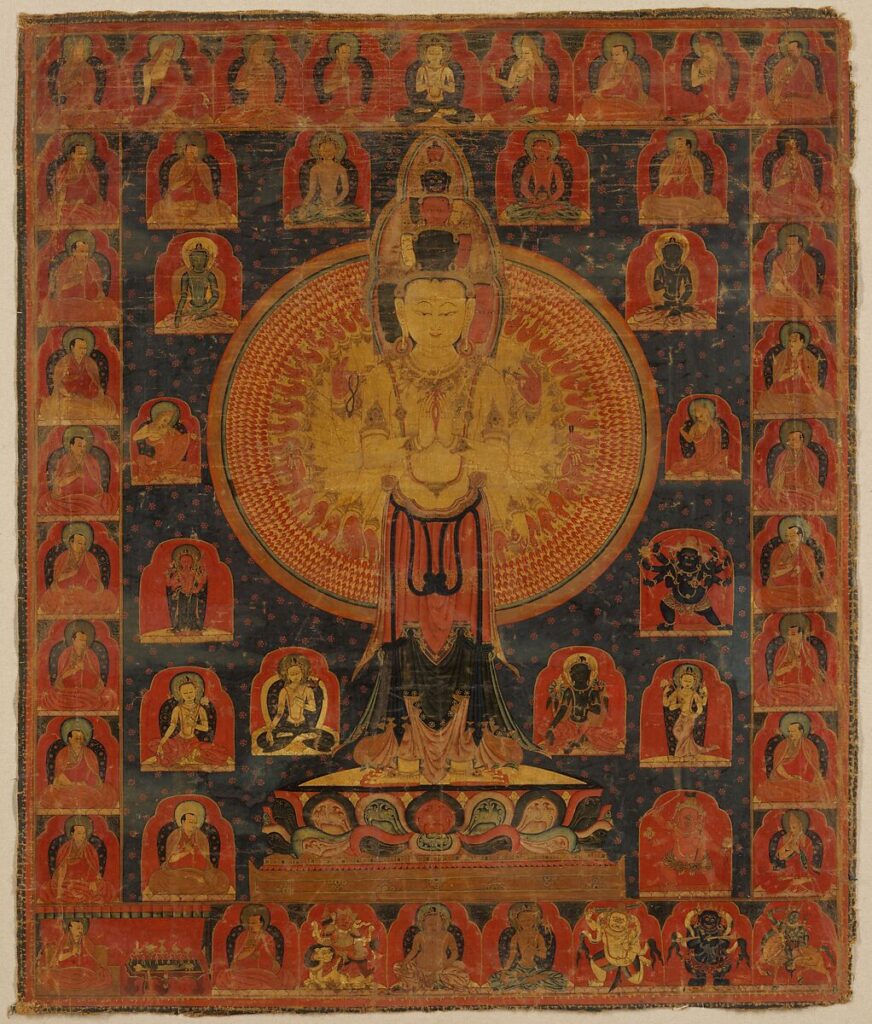

Figure 5 is extraordinarily interesting because it centers around a commanding figure rather than a shape. Here, the eye is drawn immediately to the figure in the center and its sheer size demands attention and creates emphasis. The figure in the center is a rare depiction of Chenresi, “a cosmic form of the Bodhisattva Avalokiteshvara” (MET) who is known as the embodiment of virtue and compassion (“Bodhisattva Avalokiteshvara in the Water-Moon Manifestation (Shuiyue Guanyin)”, n.d.). Here he can be seen to have ten heads and one thousand arms that fan out around him. The eyes seen on the palms of his hands represent his power to “radiate wisdom in every quarter of the universe.” (MET) He is surrounded by small, circular niches that each contain a figure most likely a protective deity of some sort.

To best present the most variety of mandalas possible, the following examples presented are made of drastically different mediums and do not visually resemble each other as much as the previous pieces presented do.

Unlike any of the other pieces included in this chapter, Figure 6 is not made to outlast the creator. Instead, it is the fact that it is impermanent that makes it so significant. Displaying all of the typical characteristics of a mandala discussed throughout this chapter (center point, emerging design from the center, square and circle shapes and patterns, intricate designs) this mandala is easily identifiable. The sheer amount of color that is used in this piece is one aspect that makes it stand apart from the rest of the examples in this chapter. Rather than just using a couple of different colors, this piece utilizes nearly all of the primary colors. The only other pieces included in this chapter that even gets close to doing the same are the painted mandalas discussed earlier.

The practice of making a mandala with sand, belaboring over it for hours and days at a time, and then wiping it clean is quite common as its demonstration of impermanence and sacrifice helps the practitioner live and appreciate the present moment. (Van Gordon). Typically the sand is mixed and then placed in a body of water as some sort of offering to the deities. It can be seen in the documentary film that the older monks are the creators and the younger boys in the temple watch so that they may learn the practice and one day complete the task themselves when they are older, thus continuing the tradition.

Much like Figure 6 previously discussed, what makes this piece stand out the most is the material it is made out of. The use of squares and circles to organize the pattern and provide the piece with its easily recognizable mandala iconography. In this piece, however, it is not just the sheer amount of detail portrayed that indicates its value, but it is also the luster of the gilded metal of which it is created.

Depicted in this piece are images conveying a flame circle, funeral grounds, and a ring of lotus petals which is inlaid with turquoise. (Fisher) There is also a gateway depicted whose bottom is falling outwards, beckoning the viewer to enter into the mandala and thus the celestial realm it (the mandala) represents.

Concluding Thoughts: What is Asian Art?

To me, Asian Art is any art that was created in Asia. I know this may seem like an overly logical answer but I feel as though this definition (despite not being very poetic) fully includes all pieces that I believe should be considered Asian Art. Asian Art is deeply rich in culture and color and it is never just what meets the eye. Every piece has a deeper meaning, even something as popular and replicated as the mandala. However, despite the richness of culture and awe that these pieces inspire, compared to their European counterparts, Asian Art has a very difficult time keeping up. I believe that the more people we can introduce Asian art in all its glory to, the more Asian art will be able to catch up to European Art in its popularity. This increased awareness of Asian art would also be a very important step forward in the respect for and preservation of important pieces of art and associated Asian cultures, many of which are slowly dying out due to a lack of interest. Preservation of these cultures is essential for the future of humanity to understand its past fully, and without Asian art, we lose a core part of who we are as a species. To conclude, yes, I believe Asian art is any art created in Asia, but I do not think that the stories these pieces have to tell should stay there.

Reading List

Bell, Chris. 2020. “Mandala.” Encyclopedia of Buddhism. https://encyclopediaofbuddhism.org/wiki/Mandala.

“Bodhisattva Avalokiteshvara in the Water-Moon Manifestation (Shuiyue Guanyin).” n.d. Yale University Art Gallery. Accessed May 10, 2023. https://artgallery.yale.edu/collections/objects/8135.

Fisher, Robert E. 2011. Art of Tibet. N.p.: Thames and Hudson. https://moodle.conncoll.edu/pluginfile.php/411233/mod_resource/content/1/Fisher%20Tibetan%20Art%20ch.3.pdf.

Metropolitan Museum of Art. n.d.

Van Gordon, William. 2017. “The Mandala of the Present Moment – Mindfulness.” SpringerLink, (Aug). https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s12671-017-0779-x.