Katsuhiro Otomo’s feature length animated film Akira (1988) shocked audiences globally with its unique cyberpunk aesthetic and grotesquely beautiful body horror. Adapted from his manga series of the same title, this type of speculative fiction can be particularized to the period in which it was released. The film served as most of the world’s primary exposure to anime and helped defeat the stigma of animation being solely used for children’s entertainment. The cultural impact of Akira can be observed in many facets of popular media: from music videos to computer games.

The character Akira is an esper whose psychic powers are what cause the instant destruction of Tokyo in 1988, signaling the start of another world war. His omnipresence subverted through most of the film is meant to represent absolute power and the follies of human progress. The events of Akira occur 31 years after World War III in a city built above the razed Japanese capital. In its place rises Neo-Tokyo, a city whose appearance is inseparable from the historical and architectural contexts that conceived it. High technology is juxtaposed with the symptoms of societal decay, suggesting a troubled future not dissimilar to the present. Neo-Tokyo is ripe with conflict at every level: from the corrupt parliamentarians down to the high-octane biker factions who terrorize the streets. The film weaves multiple narrative threads by involving a cast of perspectives who provide a holistic view of Otomo’s dystopic urban landscape.

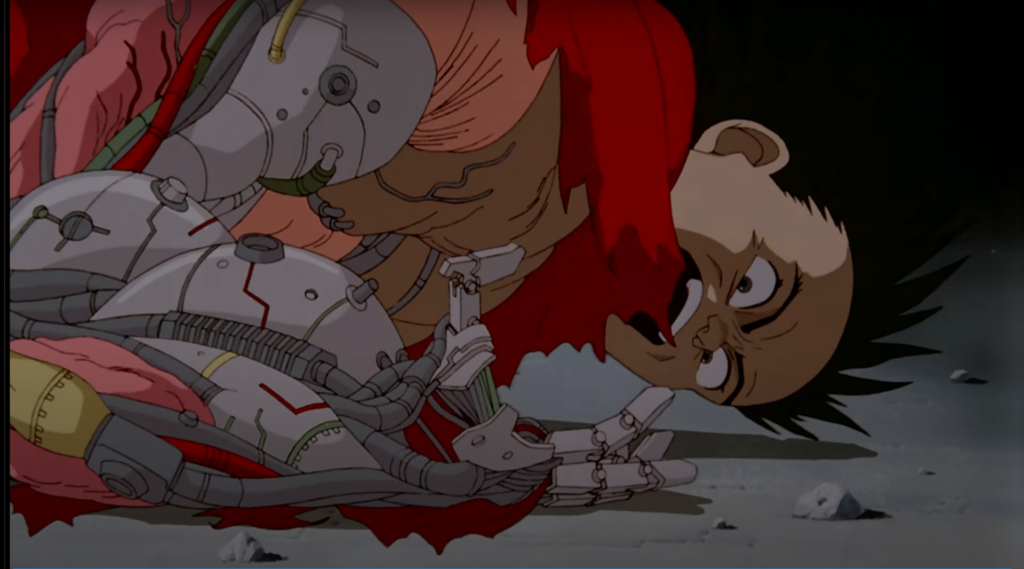

At the story’s focal point is Tetsuo Shima, a teenage biker whose collision with a patient escaping from a secret laboratory instigates the plot. The crash not only hospitalizes Tetsuo but imbues him with similar psychic abilities to Akira’s. This power mutates and evolves throughout the movie, forcing the supporting characters to try to prevent another catastrophic annihilation of the city and its inhabitants. Tetsuo’s internal state is articulated through repeat headaches and hallucinations, further alienating him from his friends, which prompt him to seek out the cryogenically stored remains of Akira. While the film suffers from an arduously complex plot, themes such as camaraderie, humanity, and the cycles of existence are brilliantly staged within Akira’s visually detailed, post-nuclear narrative.

To fully comprehend Otomo’s aesthetic choices and inspiration, the conditions of his social and material environment must be considered. Born in the wake of post-war reconstruction in 1954, Katsuhiro Otomo bore witness to Japan’s structural reformation through western intervention. Consequently, the emphasis on constructive development neglects the human element of statecraft. The children captured in Hayashi Tadahiko’s Days in Dregs (1980) photo series are raised by the scarcity of a society ravaged by war. Orphans at the mercy of a government that fail to provide adequate guidance is a major part of Akira’s plot. Tetsuo and his biker gang are all orphans that embody the youthful unrest of Neo-Tokyo. The unhealthy behaviors exemplified by Japanese children and teens in both the photo and the manga panel is analogous to the nation’s wellbeing postwar. The popularity of the Bōsōzoku subculture, associated with custom motorbikes and rebellious youth, peaked around the early 1980s while Otomo started to illustrate his manga. This grimy undertow contrasts against the megapolis enabled by an economic miracle. Japan’s rampant reconstruction overfertilized by global markets provided much of Otomo’s inspiration to write and direct Akira.

(right) Katsuhiro Otomo, Akira, Film, 1988, TMS Entertainment

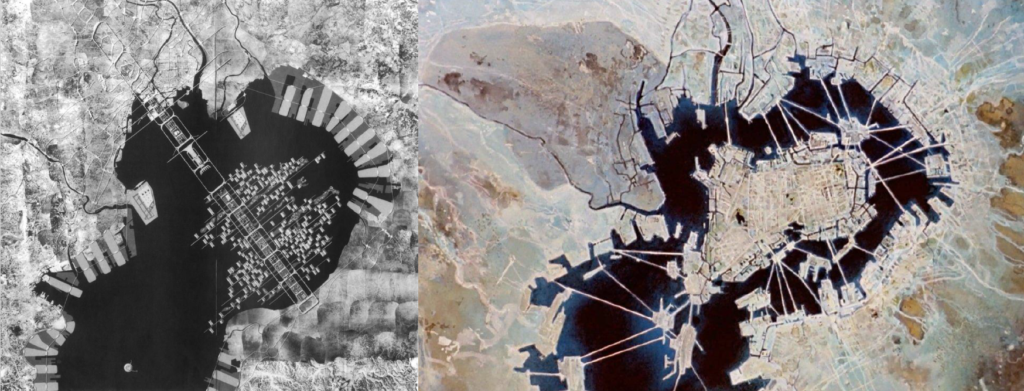

The advent of the Metabolist movement was initiated by the designs of Japanese architect Kenzo Tange. Metabolism, born from a utopian impetus to create a new urbanism, is a philosophical school that synthesizes the traditional Zen doctrines of transient existence with western ideas of structuralism. Tange’s 1960 plan imagined a new physical order to support Tokyo’s revitalization by unifying urban architecture into an organic whole. The megastructure spanning across Tokyo Bay was intended to accommodate the city’s growing population. Akira reveals Neo-Tokyo with an establishing bird’s-eye shot showcasing Otomo’s rendition of Tange’s concept. Neo-Tokyo’s development abandons linear development in favor of a haphazard sprawl, denying the spatial impermanence characterized by Metabolism.

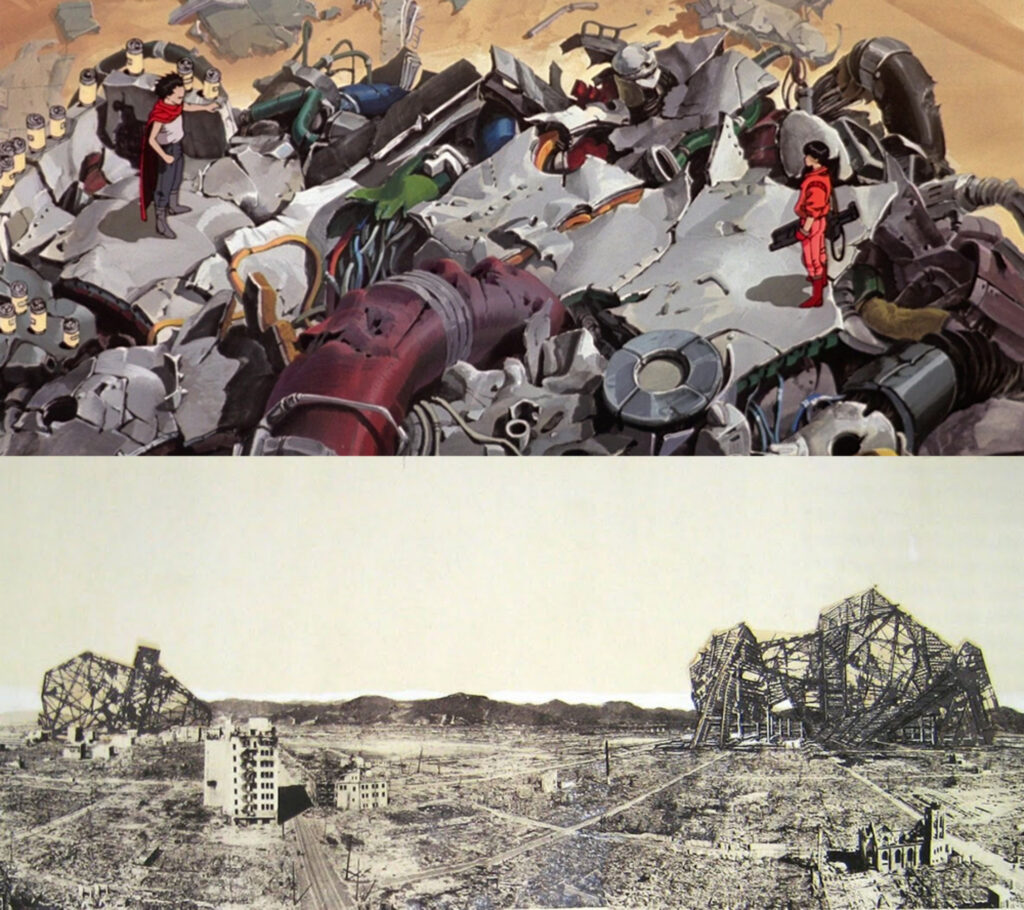

Japanese modernists struggled to conceive a city of the future beyond the imperial void that designated spatial experiences. Urban development and land reform experienced a metamorphosis after World War II when the state superseded the emperor, shifting the spiritual landscape and national identity. Architect, theorist, and disciple of Tange, Arata Isozaki instinctually retained the centralized void ubiquitous to Japanese design. For Isozaki, an eyewitness to the bombing of Hiroshima, the image of ruin was adopted as a sign expressing simultaneous death and rebirth. “Ruins are the style of our future cities, Future cities are themselves ruins,” poignantly captures the ephemerality and near-futility of urban design (Isozaki, 87). His Electric Labyrinth installation at the 14th Milan Triennial included a mural of destroyed future megastructures placed in Hiroshima after being leveled by nuclear technology. These apocalyptic cultural motifs that shaped a generation signaled the start of Japan’s reconstruction period. Akira utilizes the same ruinous set pieces of the old city to frame pivotal action sequences. Here, past and future coexist under the same threat of total annihilation. The self-destruction of cities from the perspective of Japan-ness cannot escape the inevitable reset, whether it be at the hand of man or nature. When the progress of urban development is understood as a manifestation of vital human power, the city can only be understood as a process that guarantees future ruins.

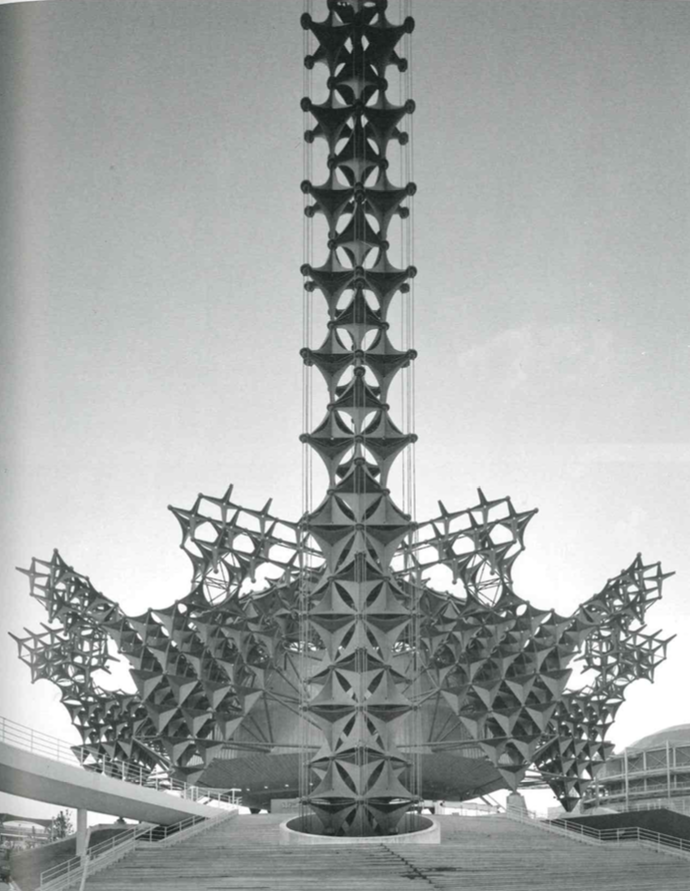

On the world stage, Japan hoped to convey progress and harmony for mankind through innovations in architecture and technology. The Toshiba Pavilion, built for Expo ’70 in Osaka, was designed by Kisho Kurokawa. The modular megastructure captures Metabolist principles with its dynamic form. Its steel plated ‘tetra-frame’ skeleton and complementary spheroid center evokes a biomorphic cellular structure. The plaza, a western architectural device, had no formal history in Japanese construction. Metabolism lost its status as an avant-garde movement with its final display at Expo ’70, which “was rather a commercial project in the manner of EPCOT Center, except that it enjoyed state sponsorship,” (Isozaki, 71). A decade of technological and economic progress later and Akira emerges into the post-Metabolist world.

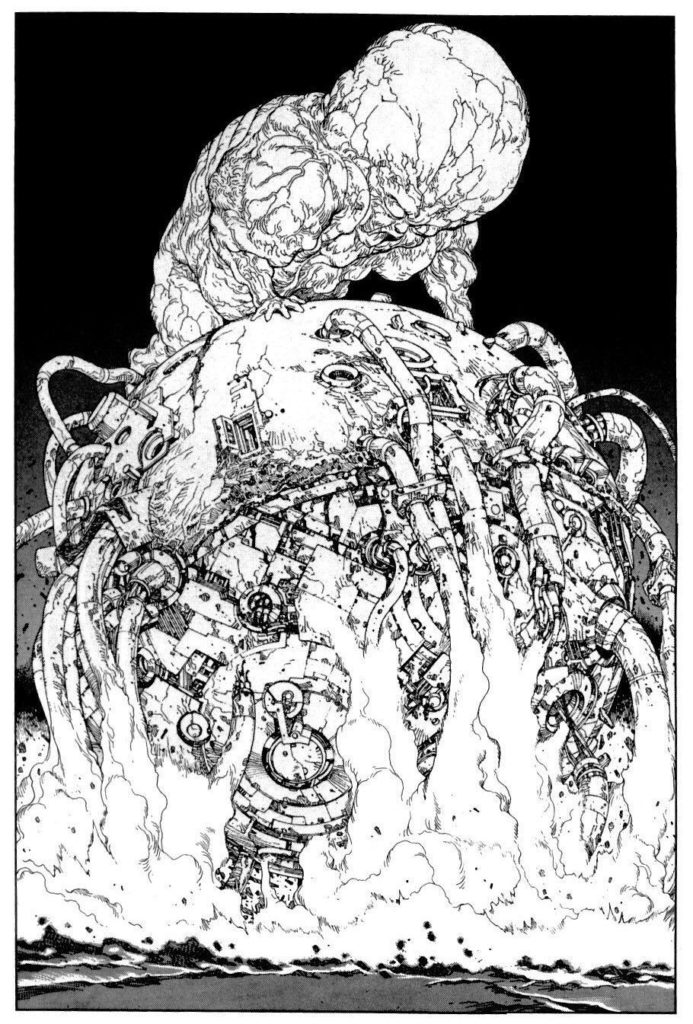

After his rampage, Tetsuo’s loses his arm, causing him to take on a makeshift robot prosthetic. This does not get him far, as the cells and hardware of his body mutate beyond control. The amalgamation of technology paired with natural forms resembles the elements that constitute the Toshiba Pavilion. While Tetsuo’s power destabilizes, his body metabolizes out of control, shaping him into a colossal baby. On the brink of destruction and certain collapse, Otomo offers a symbol of rebirth from the mass of flesh and wires. Akira is revived to stop Tetsuo’s growth and creates a singularity that destroys the city once again. Earlier in the film, the parliament member and resistance leader Mr. Nezu predicts this event while observing the city: “New Tokyo’s going to change soon. In all respects this city is saturated. It’s like an overripe fruit. Buried within it is a new seed. We need only wait for the wind which would make it fall to fruition. The wind called Akira,” (0:44:10). This likening of Neo-Tokyo to an organic body closely aligns with Metabolist philosophy. Otomo espouses a cautionary rhetoric about the unrestrained development of science and technology through his fictional account of postwar reconstruction.

Within the world of Akira is a failed Metabolist utopia. The film translates Otomo’s experience, despite witnessing major economic growth, observing social unrest in the dregs of his country. Japan was reconstructing, but no one knew to what end. When the tenants of Japanese Buddhism are examined, two types of cataclysmic events inspire empathy for the ephemeral essence of life: one caused by material ambition and the other by the wrath of nature. Metabolism does not distinguish between man and his world but recognizes his efforts as directly correlating to observable phenomena. “According to the hermeneutics of Japan-ness, even instantaneous annihilation could be broadly regarded as an act of nature,” (Isozaki, 84). Wabi-sabi, or the transient beauty of existence illustrated by the complete destruction of whole cities, is deeply seated in the Japanese pantheon. Akira articulates this through the drawn-out destruction of Neo-Tokyo at the end of the film. In certain ways, the city transcends once all its structures are obliterated, waiting to be inherited by a new societal compulsion.

Bibliography

Tucker, Anne, Kōtarō Iizawa, and Naoyuki Kinoshita. The History of Japanese Photography. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press in association with the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, 2003.

Ōtomo, Katsuhiro. Akira. New York, NY: Kodansha Comics, 2017.

Akira. Japan: Toho Co., Ltd., 1988.

Tange, Kenzo. 1959-1960. A Plan for Tokyo, 1960.

https://library.artstor.org/asset/AWSS35953_35953_29410250.

Isozaki, Arata, Sabu Kohso, and David B. Stewart. Japan-Ness in Architecture.

Cambridge, MA: The Mit Press, 2011.

Steele, James. Contemporary Japanese Architecture: Tracing the Next Generation.

Abingdon, Oxfordshire: Routledge, 2017.