Overview

The goal of this project is to thoroughly analyze the characteristics, development, and fundamental relationship between Zen Buddhism and Chashitsu, the traditional Japanese tea house. This work explores the symbolic meanings, functionalities, and materials associated with each feature of architecture, including Roji(garden), Nijiriguchi (crawling in entrance), Tokonoma (alcove), Chabana(flowers), and windows, while examining the enduring influence of Zen Buddhism on the identity and function of tea rooms or tea houses throughout Japanese history. Although the meaning and functions of Chashisus have changed throughout time and space, I intend to explore the Buddhist spatial qualities through the use of different images taken over a period of time in explaining the intrinsic connection between the features of Zen Buddhism and Chashitsus. I am personally interested in this project because I believe that architecture is the framework of cultures and plays a significant role in the development of shaping identities. By restricting or encouraging bodily movements, thought processes, ideologies, and philosophies, our space plays an indefinite part in our lives. By making the connections between the application of Zen ideals in Japanese tea room spatial qualities, the embodiment of Buddhism ideas amongst individuals can be explored.

Introduction

A chashitsu is a historical Japanese tea room or tea house established especially for the practice of the tea ceremony sometimes referred to as “chanoyu” or “sado.” It is a venue where visitors can congregate to enjoy the beauty of the tea house itself, engage in mindfulness, and experience the art of tea. The Chashitsu is strongly linked to Zen Buddhism and embraces the ideals of mindfulness, transcendence, discipline, harmony, simplicity, and closeness to nature. Constructed from natural materials with a humble appearance, these cottage-styled, historically small spaces have wooden floor layouts and a Roji (garden) attached to them, which is essential for a Chashitsu to be used as a formal tea ceremonial space.

Although tea rooms and tea houses have had multiple introductions and reintroductions into Japanese society, the tea master Sen no Rikyu (1522–1591) had a considerable impact on its style and cultural significance. Riky, a significant person in Japanese tea culture, perfected the art of tea and highlighted the wabi-sabi principles, turning tea drinking into a peaceful activity. His lessons had an impact on the design and aesthetics of Chashitsu, resulting in its distinctive features. All tea masters, including Rikyu, studied Zen, and according to Okakura sought to implement it into their daily lives, reflected by the saying: “Zen and tea are one” which reinforces the importance of Buddhist ideologies in Chashitsus.

Even though the Chashitsu does not necessarily serve a religious purpose, its connection to Zen Buddhism and the tea ceremony does help link it to the larger spiritual and intellectual facets of Japanese culture. It offers people a physical environment and a ritualized practice in which individuals partake in mindfulness, introspection, and a feeling of harmony with oneself and the rest of the world. It has served many purposes, from Monks seeking refuge and meditating in them during periods of war during the Sengoku Period (1467-1598) to the elite and wealthy Samurai class formalizing the space for their elaborate and elegant tea ceremonies.

However, certain qualities and attributes have remained consistent and are signature to the style of a chashitsu. The following images intend to explore such attributes and connect them to Zen ideologies while weighing in on the use of materials, photography styles, and perspectives pertinent to each image.

Roji (Garden)

- Creator: Architect: Masao Nakamura; Gardens: Robert Bazelaire; Master carpenter: Takaaki Yamamoto

- Title: Tea Pavilion in Japanese Garden at the Musée du Panthéon bouddhique (Chashitsu) (Pavillon de thé)

- Work Type: architecture

- Date: 2001

- Repository: Musée Guimet, Paris, France

- Collection: Réunion des Musées Nationaux (RMN)

- ID Number: ART457335

- Source: Image and original data provided by Réunion des Musées Nationaux / Art Resource, N.Y.

- Photographer: Thierry Ollivier

Created by Masao Nakamura, this Chashitsu appears to be a free-standing wooden structure resembling a cottage. It is surrounded by a Roji or a natural garden that is used for formal tea ceremonies and has a path leading up to the tea room. The structure is set up in the urban environment of Paris at the Musée du Panthéon bouddhiqu to replicate a Chashitsu and is an example of the Western world attempting to encapsulate the symbolic spatial qualities of a Japanese tea room. In doing so, Bazelaire applies Buddhist Zen properties in creating the Roji which aims to foster a tranquil and peaceful environment, allowing the aura to be meditative and free from distractions, despite the physical locality of a chashitsu. Therefore, even though, this structure is in the city center of Paris, it appears to be in a natural environment. This is done through the use of bamboo plants, an artificial pond, and stones which make the tea room secluded from the man-made world. The selection of plants and flowers in the garden is also careful, for the Zen ideology does not want the scents or colors of the garden to be overbearing or distracting, rather it should create a tranquil illusion that makes the mind prepared for distraction-free meditation. This utmost sense of attention to minute details emphasizes the importance of mindfulness in Buddhism as Zen philosophy puts a high value on consciousness and being fully engaged in each moment by emphasizing attention to detail. It builds up on Heino Engel’s argument, which states that a Chashitsu is, “a space free from any outside intrusion, both actually and suggestively…this solid enclosure was affected by the realization that seclusion in the building is essential to create a maximum atmosphere of introversion in building”. Symbolically, this intends on separating the “outside world” from the “inside world” by acting as a transcending barrier between the environments. The feeling of separation from the rest of the society not only points to the peaceful and harmonious nature of a chashitsu but also strives to include Buddhist practices into daily life subconsciously.

The image also captures the stone lantern placed in the pond, near the entrance, which is used by visitors to wash their hands and remove any impurities from their bodies. It reinforces the Buddhist idea of purity of mind and body before meditation. The picture was captured at this angle to focus on the irregularity of the pond and highlights the Zen quality of imperfection, noting that nothing in a chashitsu is perfect or symmetrical, and that beauty lies in the irregularities of the world. According to Kidder, “Stones marked the irregular outlines of the pond…”, which are placed intentionally around the water body in different shapes and sizes, as a way to reinforce this belief. Furthermore, the presence of the Roji Garden further builds on Buddhist ideas of transcending the dualities of one’s reality. Buddhism and Zen place a strong emphasis on getting beyond dichotomous thinking and seeing reality without the usual categories. This idea is embodied in chashitsu architecture, which blurs the lines between the interior and exterior to create a setting where the tea room blends in perfectly with its natural surroundings. Chashitsu’s design invites practitioners to transcend the separation between self and environment and feel a sense of being one with nature.

Nijiriguchi (Crawl-in Entrance)

- Title: Meimeian in Matsue, Shimane Prefecture, Japan

- Location: Japan

- Date: 20 July 2008

Meimei-an was built in 1779 by Lord Matsudaira Harusato, who was the daimyo of the Matsue clan at the time. It’s in the Japanese prefecture of Shimane, Matsue. The Fumai-ko school of tea ceremony, which was developed by the seventh Lord of the Matsudaira to reign from Matsue, inspired the design of Meimei-an. Located near the Matsu Castle complex, which was typical for Chashitsus, this dwelling was considered to be his most beloved tea house, highlighting the importance of the tea room in Japan and stressing the role of Lord Matsudira in spreading the culture of the tea ceremony.

The image illustrates the architecturally embedded feature of a Nijirguchi, “or a crawling in entrance”. It is notably small, requiring the guest to “bend” as the environment around them completely transforms and they physically “enter” the meditative space. It is one of the few entrances and is used for the visitors to enter the Chashtisu, requiring them to pass through an obstacle before they begin their meditative journey. The picture lays emphasis on the presence of a stone beneath the “crawling in entrance” to support the person’s movement emphasizing the significance of nature in the framework of a Chashitsu and the intertwinement of nature and man in movement and meditation. The Nijirgucho hence follows the Zen philosophy of developing mindfulness, control, and discipline by following the idea of Buddhist ritualized movement, gestures, and bodily practices to subconsciously embed the ideas of control and spirituality in the individual. By directing the movement of one’s body through the entrance, philosophical and spiritual ideas derived from Buddhism are embodied in the architectural scape of a chashitsu.

The Buddhist influence can further be noticed by the act of bending and the irregularity of stones in shapes and sizes (reinforcing the Zen quality of perfect imperfection) which subtly engages the human body and makes one awake, completely present, and engaged. It serves as a Buddhist message of perpetual change and endurance while encouraging participation in a spiritual setting. The use of natural materials like bamboo, wood beams, earthy tones, textures, and stones demonstrate the humble and unpretentious nature of a Japanese tea room. It builds up on the idea of Heino Engel’s idea connecting it to Buddhism which states, “the physique of the tearoom, both as a whole and in detail, is infinite in its spiritual perception, an immense source for the exercise of art in living. It reveals abundant richness by substantiating humble poverty.” Not only does it amplify the role of bodily movement, alertness, and humbleness, but it also highlights practicality where every material – like the stone underneath the Nijirguchi used to climb into the tea room- is present to perform a function.

Tokonoma (Alcove)

- Title: Shōin Room

- Date: 1989

- Culture: Japan

- Classification: Architecture

- Accession Number: Shōin Room

The shin, which means “study” in Japanese, was formerly a reading chamber with shelves and an alcove next to a window in a Zen monastery. Although the Shōin Room is a space for studying and does not depict a Chashitsu as it does not have a hearth or fire, it consists of a Tokonoma (alcove) which is an intrinsic quality of a Japanese tea room which makes this image important in demonstrating it’s influential impact on the space. This specific alcove was expanded and made specifically for the display of artwork during the Muromachi period (1392-1573) when there was an increased interest in and collecting Chinese paintings and household items. At the same time, the “tokonoma” developed into a crucial component of Japanese formal rooms. The scale of this room, with its massive tokonoma occupying one wall and its gold-leafed doors defining the other walls, is typical of the grand chambers of the Momoyama era found in temples, aristocratic houses, as well as the extravagant castles of the recently established warlords.

Usually, a Chashitsu has a minimal amount of art, so as to not overpower the humble and precise nature of a tea room. However, one aspect that is consistently common in the structures is a Tokonoma or an alcove that has art or scrolls hung on it. As can be seen in this image, this architecturally embedded feature centers the focus of the viewer on the alcove, carrying on the minimalist ambiance of the tea room and directing the gaze, movement, and direction of the individual toward it. The scrolls can be observed on the tokonoma which is used to embody invaluable and significant art or written scriptures. The intentional vacancy and emptiness of the Chashitsu are amplified by the photographer to visualize the meditative nature of this room, requiring maximum focus and attention- which are intrinsic Buddhist Zen properties.

The Zen symbolism of Tokonoma has a strong relationship with Chashitsu and is a core component of the structure. According to Engel, “The presence of the picture recess, tokonoma, in the tearoom indicates the strong relationship of “tea” with Zen Buddhism. The Zen temple itself was but a college room for the monk students, with one wall slightly recessed to contain a Buddha statue or sacred picture, in front of which the monks held their discussions and meditational practices, burning a censer and drinking ceremonial tea.” The colliding concepts are seen throughout a Chashitsu which displays its rugged nature through natural surroundings and unpretentious choice of construction materials while still radiating a sense of precision, symmetry, and minimalism through the use of elegant art and clean and simple yet elegant layout of the room. It directly relates to the teachings of Zen, which, “ aims at simplification to the very point where subject and object can no longer be dualistically conceived. To uncover the very basis of man’s life, representation and performance of dwelling has to be reduced to the barest essentials: the hut and the drink, the tearoom, and the tea”. (Heino Engel).

This shows how minimalist designs are incorporated into the tokonoma to reduce its distraction and enhance its meaning for meditation and meditative engagement, as it manifests itself as a study room. Buddhism and Zen both place a strong emphasis on simplicity and minimalism as means of achieving peace and enlightenment. The design of the interior of this room, including simple lines on the walls and floor, organic materials, and an uncluttered aesthetic, reflects this idea. Its sparse interior fosters a calm environment that is ideal for mindfulness and meditation and ties in with the Buddhist philosophy of attaining spirituality through a humble approach toward life, as can be seen by the minimal and modest design.

The humble aesthetics can be seen through the lack of furniture as well in this image. During the Edo period, barren furniture was used to embody invaluable art meant to be enjoyed by the company of individuals consuming their tea and relaxing in the space.

Right underneath the Tokonoma, Chabana, or flowers are traditionally placed in a chashitsu which not only reinforces Zen ideals of nature entering the interior space of the chashitsu and the transient nature of the world but also highlights the inevitable role of nature in meditation.

Although Shōin Room plays with multiple textures in the image, an abstract vacuum can be sensed in the picture due to the emptiness of the room. The space embodies the idea of practicality and functionality, with an absence of furniture, which is traditional to a chashitsu as well. Engel states this as, “freedom of movement, both in spirit and material; only in a vacuum can the full extent of man’s aesthetic emotion unfold, and only through making oneself a vacuum can man’s physical and intellectual, moral and spiritual limitations be overcome”. This Buddhist idea makes the tokonoma the guiding principle of human movement, directing the meditators to center themselves towards the alcove and engage in tea ceremonies. The individual is meant to position themselves to the tokonoma for meditative purposes and in a way, center their mind and body to the ritual instead of themselves, carrying on the Buddhist theme of focus and discipline. It segments the tea ritual process by creating a dedicated space of scrolls or art, demanding focus and attention. This is consistent with Zen Buddhism’s focus on ritual practices as a way to develop self-discipline, attention, and a stronger spiritual awareness.

Tatami (Floor Mat)

- Creator: Ishimoto Yasuhiro (Japanese, 1921-2012)

- Title: Tea Room of the Shokintei Pavilion from the portfolio: Katsura, 1989

- Work Type: Photograph

- Date: 1981-1982, printed 1989

- Material: Gelatin silver print

- Measurements: 18 x 22 in.

- Description: ed. 12/31

- Repository: The Museum of Fine Arts, Houston

- museum purchase funded by Louisa Stude Sarofim

- Accession Number: 2000.4.10

- Collection: Museum of Fine Arts, Houston

- Source: Photographer: Albert Sanchez

Created by Ishimoto Yasuhiro in Katsura, this tea room demonstrates the interior of a chashitsu. As can be noticed, the room floor is covered by a traditional straw floor mat called a ‘Tatami”. It is used for visitors to sit on due to the lack of chairs or modern furniture, demonstrating the importance of humility and practicality in Zen Buddhism. According to Heino, “As a fabric that should equally facilitate walking, sitting, and sleeping, the tatami (demands)… both stiffness and resiliency. Limited to the use of natural materials, this demand could be met only by accepting a fabric with high porosity, i.e., with a consistency impractical and unhygienic for a floor, because as such it is susceptible to accumulation of dust and penetration of humidity from the damp ground”. Therefore, the straw mat allows for practicality as it acts as a good source of ventilation and does not absorb moisture, highlighting Zen properties of functionality, simplicity, and letting go of the material world.

The proportions of this image also comment on the asymmetrical, yet seemingly symmetrical proportions of the room by the focus on lines. The running tatami mats are contrasted by the structural support beams in the ceiling and the vertical bamboo sticks on the windows that are placed irregularly throughout the room. The intentional layout of the tatami mats and the positioning of the tea are Zen aspects that focus on paying attention to detail. Chashitsu’s construction facilitates this philosophical idea through the ritualistic activity of awakening one’s mind to the tea ceremony and meditation. This rigorous focus on the little things inspires practitioners to develop greater acuteness to consciousness and awareness. In relation to this idea, Kidder states, “From the initial selection of the site…. to the placement of buildings, formal relationships were ignored for the benefit of dynamic and unexpected linear effects in what might be called a calculated asymmetry” (216). Although to the viewer, the room may appear to be geometrically symmetrical, these lines play an important role in creating an illusion of perfect imperfection, which is a Buddhist Zen idea. It urges the visitor to appreciate and embrace imperfection, as beauty lies in irregularity.

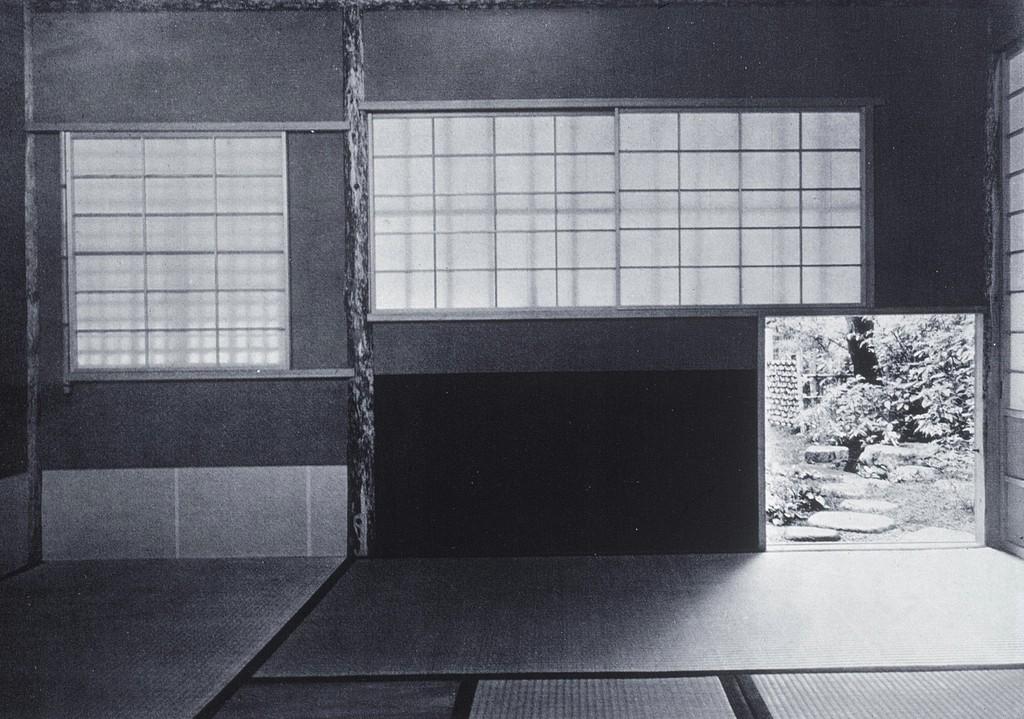

Windows

- Image: Japanese House: Int: Tea room

- Title: Japanese House: Int: Tea room

- Subjects: Architecture: Site–Japan–A.D

- Collection: Artstor Slide Gallery

- Stable URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/community.13910200

- Remote Access URL: https://shibbolethsp.jstor.org/start?entityID=https%3A%2F%2Fidp.conncoll.edu%2Fentity&dest=https://www.jstor.org/stable/community.13910200&site=jstor

- Data Source: University of California, San Diego

- Resource: Images

- File name: /fpx/ucsd/d1257/41822003451125.fpx.jpg

The impact of light and windows in the application of Zen properties in the Chashitsu architecture is also inevitable. This image of “The Japanese House: Int Tea Room” focuses on the fluidity of light in the meditative process of tea ceremonies. The windows are covered with translucent white paper and supported by bamboo sticks and wood to restrict the flow of light into the room. Instead of using glass or metal frames, the humble and natural materials allude to the simplicity of the structure and yet again, bring nature into the room. This phenomenon defies concepts of material reality and embraces humbleness as a virtue, which connects this architectural framework to Buddhism. Furthermore, the windows dictate the flow of light in the room to ensure human functionality in the room while still preserving the darkness which is essential for meditation. Engel states, “The semidarkness of the tearoom may suggest remoteness and refuge. It tempers all features of the room and blends them into harmony. Sometimes there is a limited view of the garden. But this produces neither glare of light nor a distraction of contemplating mind. Rather, this glimpse of the macrocosm, by symbolically establishing a relation between man’s moral proportions and the universe, leads man toward “innerliness,” where the true life takes place.” This sense of refuge allows the individual to dedicate themselves to the process of the tea ceremony and disconnect their body and mind from the “outside world” as they enter a stage of complete Zen mindfulness and tranquility. The shadows and light movement on the floor in the image show how the windows protect the individual from the outside and shelter them in meditation. The contemplative atmosphere directly relates to the religious philosophy of Buddhism to promote an environment for meditation that lacks distractions and urges its worshippers to devote their time, mind, and energy completely to the process of the ceremony. By muted hues of earthy tones, natural materials like bamboo and wood, dim and soft lighting, and quietness, the spatial qualities of a Chashitsu are able to embody the religious symbolism of Buddhism.

Summary

The Chashitsu: the traditional Japanese tea house and its profound link with Zen Buddhism have been highlighted in this project as a manifestation of Japan-ness, even though in reality, Japan-ness constitutes many facets. The windows, tokonoma, Roji, Chabana, and Nijiriguchi, among other characteristics and elements of the chashitsu, have revealed their symbolic meanings, practical applications, and connection to Buddhism. Although the tea room or tea house has changed over time as a result of adaptation to Japan’s shifting social and cultural environment, Zen Buddhism has remained a constant throughout these changes, filling the chashitsu with its ideals and directing the formation of its identity. This sense of adaptation, resilience, and constant transformation as a way to respond to the changing realities induces our ideas of what Japan-ness is. The reality is that Japan-ness is constantly changing, while simultaneously remaining true to its roots and informing the identity of its signature architectural elements. Our perception of Japan-ness has, is, and will constantly evolve, for no singular mention can encapsulate what it wholly is.

Bibliography

Bibliography

Anido, Julien. “Japanese Garden of the Buddhist Pantheon: Un Jour de plus à Paris.” Un jour de plus à Paris | L’incontournable des visites culturelles et touristiques à Paris. Balades, visites guidées, découvertes insolites… Visitez Paris autrement !, August 10, 2020. https://www.unjourdeplusaparis.com/en/paris-vert/jardin-japonais-pantheon-bouddhique.

Architect: Masao Nakamura; Gardens: Robert Bazelaire; Master carpenter: Takaaki Yamamoto. 2001. Tea Pavilion in Japanese Garden at the Musée du Panthéon bouddhique (Chashitsu) (Pavillon de thé). architecture. Place: Musée Guimet, Paris, France. https://library.artstor.org/asset/AWSS35953_35953_30947459.’

Carpenter, John T., and Nobuo Ito. “Japan: Tea ceremony.” Grove Art Online. 2003; Accessed 13 May. 2023. https://www.oxfordartonline.com/groveart/view/10.1093/gao/9781884446054.001.0001/ oao-9781884446054-e-90000369689.

Engel, Heino. Measure and Construction of the Japanese House. North Clarendon: Tuttle Publishing, 2020. Accessed May 13, 2023. ProQuest Ebook Central.

Ishimoto Yasuhiro (Japanese, 1921-2012). 1981-1982, printed 1989. Tea Room of the Shokintei Pavilion from the portfolio: Katsura, 1989. Photograph. Place: The Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, museum purchase funded by Louisa Stude Sarofim. https://library.artstor.org/asset/AWSS35953_35953_28294398.

“The Art of Asia.” In this room – the art of asia – japanese teahouse (Chashitsu). Accessed May 12, 2023. https://www.artsmia.org/art-of-asia/architecture/japanese-teahouse-in-room.cfm.

“The Chashitsu茶室, Tea Room.” Ippodo Gallery. Accessed May 12, 2023. https://www.ippodogallery.com/blog/90-the-chashitsu-tea-room/.

File:Meimeian08n4592.jpg – Wikimedia Commons. Accessed May 13, 2023. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Meimeian08n4592.jpg.

Japanese House: Int: Tea Room. (n.d.) https://jstor.org/stable/community.13910200

Japanese, Kubo Shunman. “Kubo Shunman: Courtesan with Client before a Tokonoma Alcove: Japan: Edo Period (1615–1868).” The Metropolitan Museum of Art, January 1, 1798. https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/77903.

“Japanese-Style Rooms.” Traditional Japanese-style tatami rooms. Accessed May 12, 2023. “Japanese-Style Rooms.” Traditional Japanese-style tatami rooms. Accessed May 12, 2023. https://www.japan-guide.com/e/e2007.html.

Kidder, J. Edward (Jonathan Edward). The Art of Japan. New York: Park Lane, 1985.

“Kyoto: Capital of Artistic Imagination .” The Met, 2021. https://www.metmuseum.org/exhibitions/listings/2019/kyoto-capital-artistic-imagination/exhibition-guide.

“See & Do.” SHIMANE. Accessed May 12, 2023. https://www.kankou-shimane.com/en/destinations/9391.

“Shōin Room: Japan.” The Metropolitan Museum of Art, January 1, 1989. https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/640986?where=Japan&%3Bft=japanese%2Btea%2Broom&%3Boffset=0&%3Brpp=40&%3Bpos=1.

Szczepanski, Kallie. “Learn about Japan’s Sengoku or Warring States Period.” ThoughtCo, September 19, 2019. https://www.thoughtco.com/what-was-the-sengoku-period-195415#:~:text=The%20Sengoku%20was%20a%20century,plays%20for%20land%20and%20power.

“Tatami Mats.” Japanese Tea Ceremony: Tatami mats. Accessed May 12, 2023. http://japanese-tea-ceremony.net/tatami.html.