Introduction

In 2019 I traveled to Germany and Austria and visited famous castles. I was amazed by their grandiosity which sparked my interest in architecture. When we started learning in class about the castles of the Momoyama period I was instantly interested. I became fascinated by the different aspects of Momoyama castles and how they are similar and different from the western castles I had previously learned about. Faced with an opportunity to pick my own research topic for my finals, I chose to investigate Momoyama castles. I intend to explore different sides of Momoyama castles, such as opulence, religion and defense. In order to do that I will be utilizing three castles as examples of each of these aspects, in order: the Nijo castle, the Azuchi Castle, and the Himeji castle. My goal with this project is to further investigate these aspects which we have learned about in class with the kidder textbook, find the connection between them and tie it back to how they represent Japan-ness.

In order to accomplish this, I have selected six images that illustrate different features of Momoyama castles. Comparing them to each other, it is possible to notice that they are similar for possessing similar basic structures, such as donjons and stone walls. However, they are also different when it comes to the different levels of each feature each of them present, for example, some of them are more opulent than others and consequently were chosen to represent that specific trait. For this reason, I chose different castles and pictures that could demonstrate the three characteristics I will be discussing.

The Azuchi-Momoyama Period

The Momoyama period, also known as Azuchi-Momoyama, lasted from 1574 to 1614. This period was characterized by political instability with various wars over the control of Japan. One after the other, Oda Nobunaga, Toyotomi Hideyoshi and Tokugawa Ieyasu were the responsibles for altering the political scenery at the time and eventually the country was unified under the central authority of Tokugawa rule. During this time, the arts and the state merged as arts began being considered a demonstration of power. This resulted in the patronage of the arts, and consequently, the production of rich and elaborate works of art and architecture. Specifically, castles in the momoyama period were unique for its interception of opulence, religious connection and defensive features.

Opulence: The Nijo Castle

The opulence part is related to the arts being a means to assert dominance. This can be noticed by use of the Shachi, mythical dolphins that guarded the castle against fire and evil placed in the roof tips. Additionally, the gates could be overly decorated and complicated. The roof tiles were circular and detailed with the crest of the castle owner. The use of gold was very characteristic of this time and symbolized wealth and power. Some castles included paintings on sliding doors made with gold in specific rooms. Having this in mind, I imagine the reason why gold represented power might have been not only because of the economic power of the warlords itself, but also because utilizing gold in so many extensive and extravagant decorations could only meant that they had so much gold in excess that the gold used in decorations for the sake of aesthetics was not missed and did not affect their overall wealth. On the topic of the subject of said paintings, it was common to observe nature, such as flowers and animals, as well as historic events.

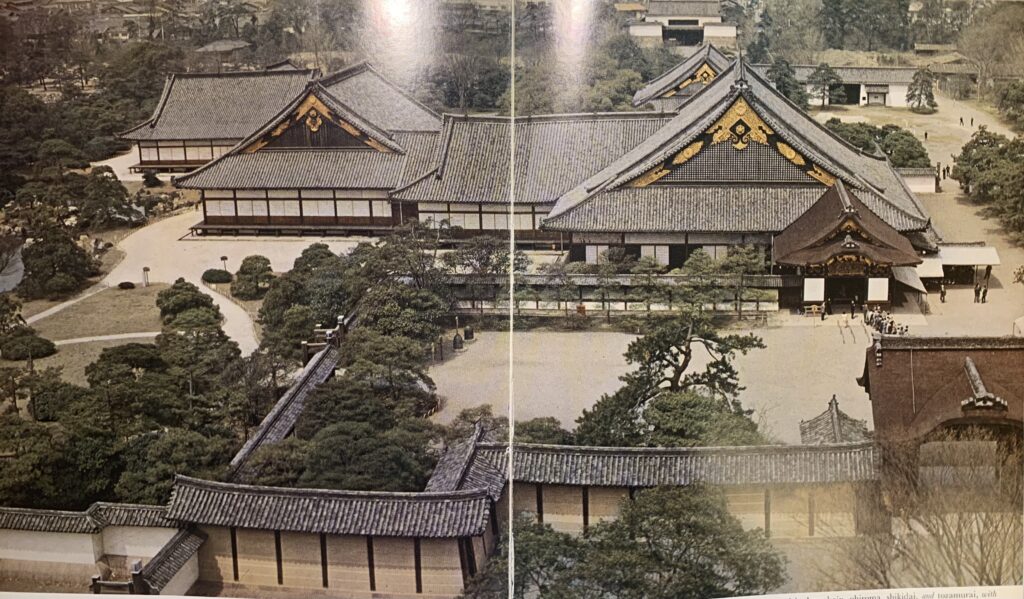

The Nijo castle is a great example of the extravagance of the time. The Nijo Castle was completed between 1603-1604. It was constructed in Kyoto by Tokugawa Ieyasu with the purpose of having a fortified residence to accommodate him in his visits to the city. There are six connected buildings following the shoin-zukuri style. The castle presents triangular gables with gold details, flowers, leafs and dragon figures and colored wood carvings in the shape of animals such as birds. The roof is made with circular tiles, detailed with circular shapes at the center. It is possible to observe a lion-like figure at the tip.

In this image it is possible to observe the buildings shiroshoin, kuroshoin, ohiroma, shikidai, and tozamurai respectively from left to right. The entrance corresponds to the kuramayose. The kuramayose structure has a Karahafu style of gable. Although difficult to see from afar, it also decorated with flowers, leafs and circular lines. Right below the karahafu gable, there is some work of flowers, birds that appear to be peacocks and a dragon on top. They seem to be sculpted on wood and covered in cold. The gables of the other buildings also have gold flowers and leaves. The roof has a triangular shape with ends that tilt upwards. The tiles have a circular crest at the center. The walls are white and there are trees surrounding the castle.

On the interior, the Nijo castle has multiple rooms with walls decorated with paintings in gold done by the Kano school, such as the Ohiroma first and second room, displaying the images of pine trees.

This picture depicts the first room of the Kuro-shoin building. The walls are painted with a gold color. On the walls closer to the viewer, it is possible to observe a cherry blossom tree with white petals in what seems to be an island with green grass surrounded by a blue river, with clouds above. Further away, on the side walls, we see a continuation of the blue river with another cherry blossom tree of the same color. Facing the viewer there is a pine tree with green leaves. The ceiling is composed by squares, with circles of different colors inside, such as green, white and red.

Religion: The Azuchi Castle

The religious connection was also present with the use of paintings inspired by buddhist ideas inside of certain castles, as well as religious structures such as relic halls.

The Azuchi castle built by Oda Nobunaga was built in a strategic location that allowed Nobunaga to observe his enemies and control the north-south and east-west routes of Kyoto, besides having the advantage of being close to the imperial court. Although also a great example of aesthetic purposes of Momoyama castles for displaying various colors such as red, blue and gold, and exhibiting gold paintings completed by Kanō Eitoku in multiple floors, the Azuchi castle’s architecture is unique for being influenced by religious principles.

The castle had six floors and a basement. From the basement to the second floor, there was a stupa for Prabhutaratna. The fifth floor had an octagonal shape and was dedicated for a Buddhist hall with walls, ceiling, and floor covered by red lacquer and gold. Additionally, there were paintings of Buddhist elements. Finally, The sixth floor was squared with pillars and floor covered in black lacquer. This time, the walls showcased paintings in gold of Confucian principles.

Here we observe the six floors of the castle over the typical stone wall of castles of the Hirajiro style. The outer walls are blue in the bottom half, and white in the upper half. There are blue bell shaped slatted windows. The upper floors are decorated with gold details, there are mythical dolphins at the tip of the roof. The fifth floor is octagonal and presents red straight lines. The sixth floor is square, fully covered in gold. There is something hanging from the ceiling. The roof’s tips tilt upward and have rounded tiles.

During the Momloyama period, many memorial buildings were decorated with gold and vegetation, such as pine trees and flowers. It is possible that such elements symbolized the gardens of the Jōdo Pure Land in Buddhism. Having this in mind, the paintings in gold done by Eitoku which revealed animals and nature in the Azuchi castle can be interpreted as yet another religious aspect of the castle.

As the name suggests, this is the painting of a maple tree. The picture focus more specifically on a single branch. There is a predominance of earth tones with a brown branch, green and reddish leaves. It is possible to identify white balls but it is uncertain what they are. Everything is laid on top of a gold background.

Putting all these factors together and considering the contact Oda Nobunaga had with Jesuits, it is possible that he took inspiration from powerful figures of the west who associated themselves with divine figures as a way to assert power in order to promote his divinity. Personally, I have learned about Louis XIV, the sun king, who linked his image to the sun god and utilized the arts to exhibit his power. It seems plausible for me that Nobunaga would have taken other western figures as a source of inspiration, and then made use of Buddhist and Confucianism to portray himself as a god.

Defense: The Himeji Castle

The defensive features are a result of the necessity to protect the castles in this time of political instability. Among the defensive features there were routes made to be deceitful, machicolations (overhanging aprons) to drop objects on attackers, walls oddly designed with difficult angles to confuse attackers, the donjon (a tower with difficult access), steps in the back meant to escape, loopholes built into the parapet used by archers and firearms, Yagura castle towers meant for observation. Other features included stone walls with rocks of different sizes held together by their own weight, stone-faced ramparts, tile-roofed parapets, fortified gates, corner turrets and moats surrounding the castle. To enter the castle one must go through gates, bridges and moats making the enemy vulnerable.

One example of reinforced momoyama architecture is the Himeji castle. Located in the city of the same name, the fortification originally belonged to Akamatsu Sadanori. After a succession of rulers, Nobunaga conquered the Harima district and Hideyoshi became responsible for this area, who then began using the fort as his strategic headquarters, later expanding it and turning it into a castle.

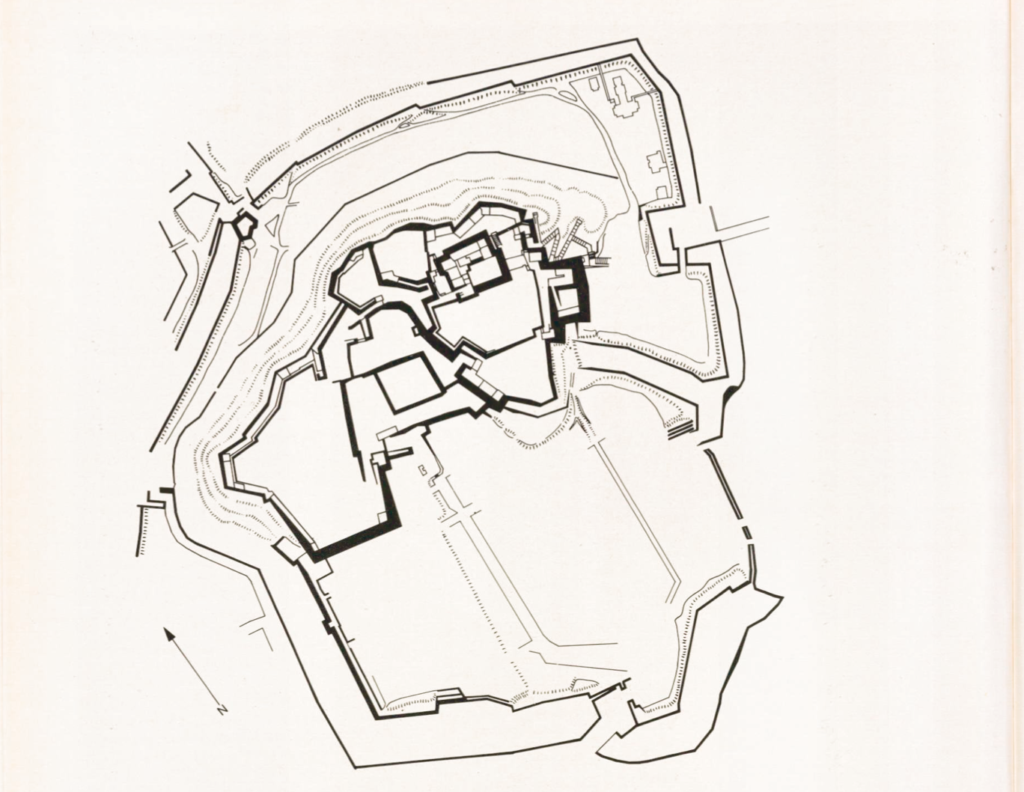

The Terumasa’s castle has three enceintes, three moats separating the castle town, samurai, footsoldiers, townsmen quarters and inner castle with another six enceintes. There is a complex of four donjons. Small and narrow fortified gates, high stone walls, breastwork and turrets are combined to increase the sense of protection. Additionally, the Himeji castle presents bell shaped windows and lattice squared windows used for protective and decorative purposes. Lastly, the walls are covered in white plaster made with lime which prevents fires.

Depicted here, there is the stone wall made with rocks of different sizes and with a sharp corner pointing to the moat not seen in the picture. The walls of the castle are white. The windows of the closer tower are squared and slatted. In the further away donjon we notice the bell slatted windows. The tiles are grey and rounded and although not seen in the picture, there is a flower shaped crest of Sakai Tadazumi’s family. The corners of the roof tilt upwards and have shachis on top. We see gables of different types such as kara-hafu and chidori-hafu.

Overall, the castle’s features are labyrinth-like due to the irregular spiral plan with multiple gates meant to slow attackers and facilitate a counterattack.

As noticeable, the castle is surrounded by a moat. I presume the squares represent the donjons. The thicker line might be the stone wall surrounding the castle. From left to right we observe the west compound, second compound and inner compound. The third compound is right below the second compound. The walls are cut at odd angles and seem to gradually get closer to each other, becoming narrower as they approach the inner compound, similar to a maze.

Conclusion

In conclusion, Momoyama castles showcase both opulence, religious principles and defense features as it is the example of the Nijo, Azuchi and Himeji castles. These traits are intertwined as buddhism influenced the arts and architecture, which in turn were a reflection of the political instability of the time leading to extravagant art as a way to demonstrate power and fortifications to prevent attacks.

Japan-ness is a problematic created from the gaze of foreigners. In the 19th century, Westerners began collecting Japonaiserie. This later influenced impressionism and art nouveau. This preference for Japonaiserie art caused a change in Japan. Art specialists began selecting from among everyday japanese items what could possibly appeal to westerners, this means that since the beginning, Japan-ness conformed to an outside gaze. Some of the main characteristics of Japan-ness are “ simplicity, humility, purity, lightness, and shibusa”.When it comes to architecture design, it was around 1930 that the concept of Japan-ness got disseminated, as a result of Japan’s modernization and adoption of western style.

The architect Sutemi Hariguchi “rated historical architecture by its measure of Japan-ness” (Isozaki, 12). In other words, he preferred native Japanese Style and Wayo style, which involved simplicity and lack of decoration, over Buddhist Styles. According to Bruno Taut, a German architect, there is a distinction between honmono and ikamono, the first meaning a more simple style of architecture while the second is more elaborated. It is said that honmono was preferred as a representation of Japan-ness

This is intriguing because my project involves the opulence of Momoyama castles and the influence buddhism had on the art and architecture of the time. I wonder if castles from the Momoyama period go in the opposite direction of honmono and fit into ikamono for presenting detailed decorations. On the other hand, some castles are extravagant on the outside, but simple on the inside. For example, in the 247 of the textbook “Art of Japan” by Kidder there is a picture of the interior of the fourth floor of the main donjon of the Himeji castle in which it is possible to notice that it is made of wood and possesses no ornaments. Thus, I contemplate if that means Momoyama castles can also fit into honmono. Perhaps this division is not so binary, and the fact that Momoyama castles can fall under both can also mean Japan-ness.

Bibliography

Text:

Schmorleitz, Morton S. Castles in Japan. C.E. Tuttle Co., 1974.

Kidder, J. Edward. “The Momoyama Period.” The Art of Japan, Park Lane, New York, 1985.

Canaday, John. “Momoyama: Essence of Japanese Style.” The New York Times, The New York Times, 23 Feb. 1975, https://www.nytimes.com/1975/02/23/archives/momoyama-essence-of-japanese-style.html.

“Japanese Castles.” Japan Experience, https://www.japan-experience.com/plan-your-trip/to-know/understanding-japan/japanese-castles.

“Himeji.” Grove Art Online, https://www.oxfordartonline.com/groveart/display/10.1093/gao/9781884446054.001.0001/oao-9781884446054-e-7000038180#oao-9781884446054-e-7000038180.

Kirby, John B.. From Castle to Teahouse : Japanese Architecture of the Momoyama Period, Tuttle Publishing, 2015. ProQuest Ebook Central, https://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/conncoll/detail.action?docID=1352282.

“Momoyama Period.” Grove Art Online, https://www.oxfordartonline.com/groveart/display/10.1093/gao/9781884446054.001.0001/oao-9781884446054-e-7000058980#oao-9781884446054-e-7000058980.

“Azuchi Castle.” Grove Art Online, 2003, https://doi.org/10.1093/gao/9781884446054.article.T005494.

Coman, Sonia. “Azuchi-Momoyama Period, an Introduction (Article) | Khan Academy.” Khan Academy, https://www.khanacademy.org/humanities/art-asia/art-japan/x97ec695a:azuchi-momoyama-period/a/azuchi-momoyama-period-an-introduction.

Julian, David. “Azuchi Momoyama Period Art, Architecture & Pottery.” Study.com, https://study.com/academy/lesson/azuchi-momoyama-period-art-architecture-pottery.html.

“Azuchi-Momoyama Period.” Japanese Architecture, https://japanese-architecture.weebly.com/azuchi-momoyama-period.html.

“Himeji Castle.” Himeji Travel, https://www.japan-guide.com/e/e3501.html.

Cartwright, Mark. “Himeji Castle.” World History Encyclopedia, Https://Www.worldhistory.org#Organization, 6 Mar. 2023, https://www.worldhistory.org/Himeji_Castle/.

Centre, UNESCO World Heritage. “Himeji-Jo.” UNESCO World Heritage Centre, https://whc.unesco.org/en/list/661/.

“Himeji Castle 1601-09 – static1.Squarespace.com.” Art History in Schools, https://static1.squarespace.com/static/5797f07bf5e231d942a26c72/t/5afc2915758d463ef1ad901d/1526475050784/himeji+castle,+1333-46.pdf.

“Zen Definition & Meaning.” Merriam-Webster, Merriam-Webster, https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/Zen.

“Introduction to Nijo-Jo Castle.” Ninomaru-Goten Palace | World Heritage Site Former Imperial Villa Nijo-Jo Castle (Nijo-Jo), https://nijo-jocastle.city.kyoto.lg.jp/introduction/highlights/ninomaru/?lang=en.

Gerhart, Karen M. “Issues of Authority in Japanese Architecture.” Japan Pitt, University of Pittsburgh, https://www.japanpitt.pitt.edu/sites/default/files/issues_of_authority_in_japanese_architecture.pdf.

Takayanagi, Shun’ichi. “The Glory That Was Azuchi.” Monumenta Nipponica, vol. 32, no. 4, 1977, pp. 515–24. JSTOR, https://doi.org/10.2307/2384050. Accessed 1 May 2023.

Brown, Kendall H. The Politics of Reclusion: Painting and Power in Momoyama Japan. University of Hawai Press, 1997.

Watsky, Andrew Mark. Chikubushima: Deploying the Sacred Arts in Momoyama Japan. University of Washington Press, 2004.

Hickman, Money L. Japan’s Golden Age: Momoyama. Yale University Press, 2002.

Images:

Kidder, J. Edward. “The Momoyama Period.” The Art of Japan, Park Lane, New York, 1985.

Hirai, Kiyoshi, et al. “3. Development of the Shoin Style.” Feudal Architecture of Japan, Weatherhill, New-York, 1973.

“File:Miniature Model of Azuchi Castle.jpg – Wikimedia Commons.” Wikimedia Commons, うぃき野郎, 7 Feb. 2015, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Miniature_Model_of_Azuchi_Castle.jpg.

Himeji Castle. completed 1609. Artstor, library.artstor.org/asset/AIC_760029