By: Brenna O’Brien, Emmy Castano

Overview

A zen garden is a distinctive style of Japanese garden that is stylized by a miniature landscape within a garden. The garden features a carefully composed positioning of all materials within the garden. Such as gravel, rocks, moss, trees, bushes, and sand. They are intentionally used to bring about a certain feeling of relaxation and serenity. All the design elements are cautiously placed to invoke particular imagery relating to symbolism in Japanese culture. For example, gravel and sand are raked in curving and circular formations to represent the symbolism of water which exemplifies the overarching theme of nature creating a sense of tranquility for humans. In addition, zen gardens appeal to cultural, social, religious, and philosophical practices.

Analyzing Techniques

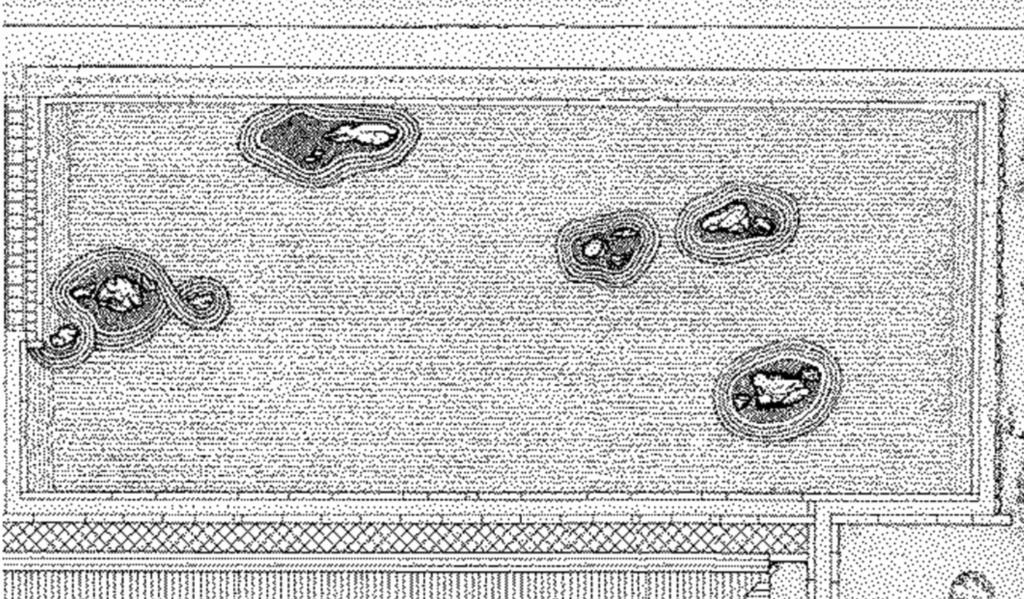

Technique plays an important role when analyzing zen gardens. A zen garden has a fixed arranged composition of the elements to offer a unique experience. The technique used to design the garden patterns is using small rakes to drag along the sand or gravel to create designs and decorations. The ripple designs are visually associated with capillary waves, also known as water ripples. From the sound of water, to the visual look of ripples, the effect of creating these designs to act as water reminds people to focus on how nature serves a sense of relaxation for the human mind. Some other popular design patterns include straight lines, chevron patterns, and wavy lines. Zen gardens have visual communication through composition and the value of line and texture from the elements within the garden. Sean McGovern’s, The Ryôan-ji Zen Garden: textual meanings in topographical form, analyzes zen garden’s environmental principles, organizations, and arrangements are conveyed into meanings of communication for philosophical and religious ideals. McGovern examines compositional arrangements of zen gardens as an embodiment of a work of art and a medium of communication. The interconnected relationship between architecture and space is used to explore senses and create a specific feeling in an environment. Positive and negative space is an element commonly used in art and architecture. Positive space is the fixed area of art within the design while negative space is the areas that are surrounding the specific subjects. Positive and negative space is a basic form that can elevate an environment. In zen gardens, design forms of line, texture, and color, are all created around positive and negative space; “The central focus of the garden design is no one particular rock or rock configuration, but centers on the relational contrast between positive space (rock forms) and negative space (unoccupied area). The rocks command attention when contrasted with the neutralized space of gravel” (McGovern 351). As seen in the zen garden in Figure 1 (and also in figure 2), the Dry Landscape Garden at Ryoanji Temple in Kyoto, Japan, the large defined stones act as the positive space, while the surrounding area is the negative space. The use of positive and negative space in architecture is important to create balance and rhythm to activate elements. The composition and arrangement of the materials in the zen gardens break down into further meanings of communication through visual elements. The large rocks in zen gardens can be interpreted as the positive space while the negative space is the surrounding open area of gravel.

Textural Configuration

The textual configuration of zen gardens is created by the design forms of gravel and sand. Zen gardens are used to present the symbolism of nature and provide a sense of physical and emotional connection to act upon the feeling of calmness, relaxation, and serenity for the spectator. Used as a place of meditation, zen gardens, are a spiritual place that invokes a sensory experience to put the spectator in a meditative state. By this, the landscape is a crucial element to creating this sensory experience. The landscape is purposefully a place where there is unclutter and clarity. Therefore, zen gardens have the challenge of being a place that should represent a connection of nature, while also acting a simple art form. Motifs and symbolic themes are used in a zen garden to achieve this goal with minimalistic and simple design features. For example, the use of gravel and sand are used in contrast to the very few large stones and trees are able to communicate the symbolic meaning of nature that is active in garden by simple and neat composition forms. Gravel is able to mimic water in the most delicate form without the ‘actual’ use water.

In Figure 3, the Kanyou Zen Temple in Kano, Yamaguchi Prefecture, is an example where gravel is used to imitate the ripple effect a water droplet has on the surface of water. The visual gradations of gravel are seen through the shadows etched in the gravel. Gravel, a simple and uncomplicated form, is used to convey a further meaning to the symbolism of water making references to nature. The gravel is also used to make various patterns through raking practices. Whether that is straight parallel lines or circular forms, the rake lines focus the spectator to concentrate on the meditative vibrations.

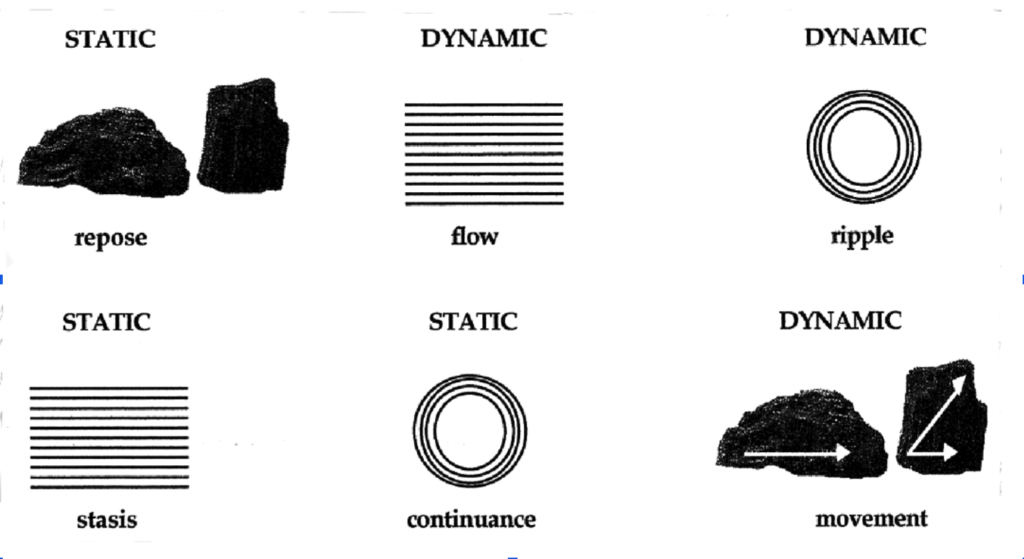

Figure 4, Textual Configuration: The Dynamics of Space and Time, is an image of the design features of rock and gravel, that generate rock-and-line and stasis-and-movement relationships in the zen garden. This can be seen in Figure 5 below, Zen Garden, Shōden-ji Temple in Kyoto, Japan by the smooth and fine horizontal lines. With the use of long rigid horizontal lines that mimic water, it gives the perception that the large stagnant topiaries are moving when everything in the landscape is static. These components collaborate to activate visual movement in a fixed and motionless area.

Scale

A final compositional and configuration element that is noteworthy in zen gardens is the scale of various features. The relationship between scale can change how one feels in a surrounding environment. The large stones work in juxtaposition with the fine gravel which overall actively contributes to the symbolism of nature and produces a meditative state. The large heavy stones are used to emphasize the attention toward iconic references of mountains in the landscape. Similarly, the fine gravel is representing rivers and rings from water droplets. The distribution of visual weight is in effect with the use of scale in the landscape. The viewer has attention to the large mighty details but does not extract the importance of the fine simplicity in the garden. McGovern, additionally studies Rudolf Arnheim’s, The Power of the Center: A Study of Composition in the visual arts: The new version. University of California Press. Arnheim analyzes the perspective of the distribution of visual weight; “Visual weight possesses a dynamic power inherent in an object by virtue of its conspicuousness, its size, its shape and its location…But visual objects, including mass, may also carry and convey their own sense of dynamics and force due to vectors, which instill the sense of movement and orient directionality” (Arnheim, 1988). The scale and weight relationship in design features work conjugation to be perceived as one unit despite the apparent differences of scale; the use of scale works together in the landscape.

The Seven Guiding Principles of Zen

Zen gardens are derived from the japanese Zen buddhism religion in which art is believed to be a powerful tool in communicating spiritual truths. With that being said, the development of Zen gardens holds significant meaning and are thoughtfully developed with certain buddhist aesthetics in mind. These aesthetics are regarded as the Seven Principles of Zen and are identified by Shinichi Hisamatsu in his classic text Zen and The Fine Arts. In this text he describes that “ the aesthetic principles are not simply ways of appreciating or engaging in artistic pursuits, but at a deeper level constitute a way of being.” (Hisamatsu, 1971) Hisamatsu was a Japanese zen buddhist scholar as well as a philosopher and tea master; although many scholars have tried to determine the principles, Hisamatsu’s iteration is the most influential and what we will be referencing here. The first principle is Kanso, meaning simplicity, which values the absence of clutter and the omission of the nonessential. Zen gardens intentionally have very minimalist designs so as not to get caught up in materialism and instead focus only on what truly adds value. They aim to express the beauty of simplification. Next is Fukinsei which translates to asymmetry. The belief is that art should embody the natural world and since nature is inherently asymmetrical, art should not try to change this and rather embrace it. The asymmetry found in zen gardens with the placement of stones of different sizes and shapes in various places aims to portray the message that there is perfection in imperfection. Following asymmetry is koko or austere sublimity. This is the most challenging aesthetic to put into words however, According to Hvass, koko captures the “furrowed, cracked, wind-dried, scarred, decayed, weathered, crackled, signs of age, worm-eaten”. In terms of art and specifically zen gardens, austere sublimity is to give form to what has no form. We see this in the usage of stones that alone have no meaning but together become a powerful symbol of zen. After that is the principle of shizen or naturalness which Hizamtsu describes as having no mind, no intent, and to be unrestrained. The goal of zen art is not just to resemble the visual field of nature but to channel the spirit of nature into the work. Zen gardens embody this by encompassing elements of nature that evoke a sense of peace and mystery and give the illusion of being a part of the natural world rather than hand crafted. The next principle is datsuzoku translating to freedom from routine. This means viewing the world through a fresh, pure perspective and breaking free of the blinders of one’s own routine and habits. In relation to zen gardens, the aim is to remove one from their routine and allow them to find peace and tranquility through the use of natural elements that fosters detachment from the outside world. After datsuzoko is seijaku or tranquility which can be applied to several different facets of zen art. Those of which being the state of mind of the artist, the composition of the art itself, and the feeling of the viewer. As far as zen gardens, we’ll focus just on the composition of art and the viewer. The open space and absence of clutter allows for a clear, uncluttered mind and the raking patterns can often provide a soothing mesmerizing effect on the viewer, both of which give a tranquil appearance and aid in a feeling of tranquility. Lastly, Yugen is the principle of profound grace. There are multiple interpretations of yugen but in relation to art, it is the subtle hinting at depth, encouraging revelation. Although it is difficult to pinpoint exactly what aspect causes zen gardens to elicit this feeling, they often do have that effect on people. The purpose of profound grace is to subtly imply depth so ultimately, there isn’t one particular thing about the design of zen gardens that is yugen but rather the overarching message that the art produces is one of substance and a deeper meaning in life (Lomas et al., 2017).

Figure 6 above is an example of a very common Japanese zen garden. Within the garden, many elements of zen aesthetics are present such as asymmetrical placement of stones, natural elements, and soothing raking patterns. Also note the wall surrounding the garden, keeping the purity of the natural world separate from the chaos of the developed society to allow for those visiting to detach. Overall, upon entering the space, you are met with a sense of profound peace and importance that cannot be attained anywhere but through immersing oneself in the beliefs of Zen Buddhism.

A Western Perspective

Traditional western style gardens are characterized by a focus on symmetry and perspective, typically designed around a central axis that is perpendicular to the rest of the structure. This style was originally developed by Bramante with his creation of the Garden at the Belvedere in Rome during the 15th century. However it then evolved into the formal french garden with the construction of the Palace of Versailles garden.

Above is the Garden of the Palace of Versailles which is one of the most famous gardens in Europe and the epitome of western gardening. Its most prominent feature is the symmetrical design with four identical quadrants surrounding the central fountain. Other notable features are the man made water fountain structure as well as the significant amount of pavement and sharp planter boxes. Overall, the garden appears to be very methodical and pristine, almost to a sterile extent. The nature of the garden feels very much artificial.

However, as trade emerged between the East and the West, it also brought the first reports of Japanese gardens to a Western audience. In 1685, Sir William Temple, an English diplomat in the Netherlands wrote about the asymmetrical gardens of the far East, which employed irregular composition to present an aesthetic vision of nature. Similarly, the French Jesuit priest, Father Attiret, wrote about the beautiful disorder of the pastoral natural countryside represented at the summer residence of the Chinese Emperor in 1743. William Chambers also wrote about Eastern gardens in 2757 after three visits to china and built the first chinese-themed garden in Europe at the Royal Botanical Gardens at Kew near London. As a result of this newfound awareness of natural and asymmetrical Eastern gardens, a turning point in Western garden design arrived with Lancelot Brown’s creation of landscapes intended to appear like natural pastures. Zen gardens then became more popularized in the West however, taking on a different meaning than the Eastern gardens’ religious ties. Today, zen gardens can be found throughout Europe, from private gardens to public spaces like museums and corporate buildings. The popularity of zen gardens reflects the enduring appeal of minimalist design and the influence of Eastern culture on Western aesthetics.

The Zen Garden at St. Mungo Museum of Religious Life and Art, seen above in figure 8, was Britain’s first permanent Zen garden, designed in the Japanese Zen Buddhist tradition to mirror the deep calm of the natural world in a highly stylized way. Immediately, it becomes apparent that this zen garden is not synonymous with those of eastern origin. Notice specifically, the absence of raked sand, replaced instead by grass and pebbles. This difference alters the feel of the garden and causes it to lack the tranquility that traditional Japanese Zen gardens possess. This garden is a mere imitation created for aesthetic purposes.

As time goes on, the west develops in their interpretation of Japanese culture, and the Temple Kosan Ryumonji (figure 9) in France is a prime example. Comparing this zen garden to the early garden above, there are several stylistic differences. First, this garden has included the aspect of raked sand and has incorporated the raking patterns around the stones. Additionally, there are zen buddhism motifs portrayed around the garden such as the Sculpture of Zen master Taisen Deshimaru seen towards the front of the image. This would suggest that in contrast to the first western zen garden being for aesthetic purposes, this garden is more intended to be a place of worship and contemplation, holding more religious value. However, it is still more cluttered than a typical Eastern garden and doesn’t quite meet all 7 principles.

Lastly, the eastern style of zen gardens reached not only to Europe but also to Washington, U.S, with the Zen garden at Bloedel Reserve (figure 10). This zen garden is the most recent zen garden created from the figures collected and it is apparent that this one has taken more from Japanese culture than the other European gardens. Perhaps, as time goes on we learn more from the East. This garden is immersed into nature and achieves almost all aesthetics but one. The lack of a wall surrounding the garden is unusual as in traditional zen gardens it is placed to keep worshipers from the chaos outside and allow them to be at peace. Other than that though, the asymmetry of the stone placement as well as the texture and raking patterns appear to be very similar to that of Japanese gardens. This garden was intended to be a place of peace and serenity but there are no prevalent religious ties and leans more towards the aesthetic of zen not the full embodiment of it.

What is Japan-ness?

Zen gardens connect to our overarching question of “What is Japan-ness?”. Japan-ness is the idea that all social, political, and economic aspects of the country’s culture create a context for Japanese aesthetics and overall reflection of history. Japan-ness can be seen in Japanese art, architecture, and other visual design representations. You can determine what is Japan-ness through styles, themes, and other motifs of Japanese culture. Zen gardens derive from Zen Buddhism which is an important emphasis on Japanese beliefs. When visually analyzing zen gardens, you can understand Japan-ness through design features and other traditional elements of Japanese culture. Such as flat surfaces or structures, wooden elements, and tiled roofing, are design features represented in zen gardens. Zen gardens are not only a way for one to meditate and find a relaxation retreat for the mind, but they speak about the importance of Japan’s culture and traditions which construct Japan-ness.

Bibliography

Images:

Kanyou Zen Temple in Kano, Yamaguchi Prefecture Image:https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Zen_Garden,_Kany%C5%8Dji_in_Kano,_Yamaguchi_pref_Japan_2005.jpg

Palace of Versailles Garden Image: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Palace_of_Versailles_Garden.jpg

Ryoan Ji, Kyoto Zen Garden Image: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Kyoto-Ryoan-Ji_MG_4512.jpg

Zen Garden, Shōden-ji Temple in Kyoto, Japan Image:https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Zen_Garden,_Sh%C5%8Dden-ji_Temple_in_Kyoto_-_2005.jpg

Harima Ankokuji Temple Image:https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Harima-ankokuji-sekitei01.jpg

Zen garden at Bloedel Reserve, Bainbridge Island Washington Image:https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Zen_-_panoramio.jpg

Sculpture of Zen master Taisen Deshimaru in the Temple Kosan Ryumonji Image:https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Sculpture_of_Zen_masterTaisen_Deshimaru_in_the_temple_Kosan_Ryumonji.jpg

Zen Garden- Geograph.org Image:https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Zen_Garden_-_geograph.org.uk_-_1280842.jpg

Stone and Sand Garden: https://www.oxfordartonline.com/groveart/display/10.1093/gao/9781884446054.001.0001/oao-9781884446054-e-8000024255?rskey=fCeFio&result=1

Sources:

Jakobus van Tonder, Gert. 2018. Visual geometry of classical japanese gardens.

Lomas, T., N. Etcoff, W. Van Gordon, and E. Shonin. 2017. Zen and the art of living mindfully: The health-enhancing potential of zen aesthetics. Journal of Religion and Health 56 (July 17,): 1720- 1739, https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s10943-017-0446-5.

McGovern, Sean. 2004. The ryoan-ji zen garden: Textual meanings in topographical form. Visual Communications, https://www.researchgate.net/publication/249671261_The_Ryoan-Ji_Zen_Garden_Textual_Meanings_in_Topographical_Form.