Which is she first?

Who is Yoko Ono? Is she the wife of legendary British musician John Lennon? Is she a Japanese woman? Is she a peace activist? Is she an artist? She is all of the above. Without one of these identities, there is no Yoko Ono. The question that persists, though, is how did her Japan-ness in America shape/influence her work? Japan-ness is defined by the judgments and selections of societies outside of Japan, specifically Western societies. The external gaze is what gives meaning to Japan-ness and the aesthetics that are associated with it (Isozaki 3). In society’s eyes, Ono is different— she is Japanese. In Ono’s eyes, she is Japanese— she is herself. Through the analysis of five works, this essay will explore Yoko’s cross-cultural perspective, the complexity of her multiple identities, and the ways in which she removes all context to just be. Her work is not always meant to critique or deconstruct institutionally traditional aesthetics; such ideological concerns and concepts are secondary to Ono’s main interest which is to establish meaning within the medium (Yoshimoto 80). Yoko Ono may be a revolutionary, but she did not reach that status without ridicule, isolation, criticism, and failure. Despite the discrimination and rejection Yoko faced, she maintained the singularity of her own artistic vision through decades of performances, prose, songs, and artwork. While some of the works discussed in this essay proved to be successful, others fell flat, perhaps because her atypical Japanese identity takes precedence over her artistry, drawing more attention to her inherently condemned reputation.

Before a visual analysis of Ono’s selected works can occur, the stage must be set. Yoko Ono, born Ono Yōko, is arguably the most notable figurehead of conceptual and performance art. Born in Tokyo in 1933, the Japanese multimedia artist, singer, songwriter, and peace activist is known for her contributions to the avant-garde artistic community. From a young age, Ono wrote poetry and plays, studied composition, and received classical voice/music training. She was the first woman admitted to the philosophy program at Gakushūin University in Tokyo. Ono not only completed many years of rigorous, elite education but also survived the WWII Allied bombings of Tokyo in 1945 (Grove Art). It was this experience that shaped her groundbreaking artistic vision and voice.

Ono is known for showcasing works that imaginatively encourage and often require interactive participation. A prime example of this is her piece titled, Painting to Be Stepped On, completed between 1960 and 1961. Four years later, Ono performed Cut Piece (1964), an act during which she sat passively while audience members used scissors to cut off her clothing. This work was ultimately recognized as a “landmark of feminist art” as it alluded to sexual violence and the female power struggle. Then, in 1972, Ono had her controversial debut in Chuck Berry and John Lennon’s live duet performance of “Memphis, Tennessee” on The Mike Douglas Show. Her role in this performance felt ill-timed and unnecessary. By 2013, the Schirn Kunsthalle Frankfurt displayed 200 of Ono’s works in an impressive retrospective. One of these works, Ceiling Painting, Yes Painting, was shown at her gallery in London in 1966. Two years later, the Museum of Modern Art presented its first (official) exhibition dedicated exclusively to Yoko Ono’s works titled, Yoko Ono: One Woman Show, 1960-1971. The exhibition explored the many issues Ono confronted such as gender, class, and cultural identity all through the lens of her bold commitment to promoting world peace. One of the pieces in the show, titled Apple(an apple sitting on a plexiglass pedestal), was given its own room… perhaps another superfluous decision.

Ono has produced an innumerable amount of work over the course of her artistic career, but these selected works not only reflect the nature of Ono’s many different identities but also disrupt the confines of traditional conceptual art. When asked if she could recall the first piece of art she ever made, Yōko said, “I remember, when we were evacuated during the war, my brother was really unhappy and depressed and really hungry because we did not have very much food. So I said, ‘OK, let’s make a menu together. What kind of dinner would you like?’ And, he said, ‘Ice cream.’ So, I said, ‘Good, let’s imagine our ice cream dinner.’ And, we did, and he started to look happy. So, I realized even then that just through imagining, we can be happy. So we had our conceptual dinner, and this is maybe my first piece of art” (The New York Times).

Although the imaginary ice cream dinner never materialized, Ono’s desire to find a new/unusual purpose for rolled canvas came to life. In one of her earliest works, Painting to Be Stepped On, Ono cut a piece of canvas not to stretch it but to place on the floor for people to step on. Rather than conform to the usual function of stretching canvas, Ono invented a new one, undermining the “fine art” status of painting (Yoshimoto 87).

That work, like a lot of Marcel Duchamp’s, might seem gimmicky. But, like Duchamp’s, Ono left more to unpack. Painting to Be Stepped On resonates with two traditions. It alludes to the well-known practices of Jackson Pollock as he created his classic drip paintings. Pollock was often photographed walking across canvases spread out on the floor without a care in the world, leaving boot prints and cigarette butts. Those photographs represent painting as performance, just as Ono sought to do in her work. The second context of Painting to Be Stepped On, identified by the art historian Alexandra Munroe, is Japanese. In seventeenth-century Japan, Christians were persecuted. One of the ways in which Christians were identified was by asking them to step on images of Jesus and Mary. This procedure was called fumi-ewhich translates to “stepping on.” People who refused to step on such images were ultimately tortured or even executed (The New Yorker). Here the work’s intrinsic Japan-ness comes to light: Ono used historical evidence of Japanese Christians fearing and refusing to step on images to argue that even viewers today will also fear and refuse to step on images, even if the image is no more than just a piece of raw canvas. People will hesitate before adhering to abnormal and uncomfortable instructions, a dead giveaway of Ono’s artistic character.

Another work that required some awkward, unnerving audience participation was Cut Piece, completed in 1964 and performed at the Carnegie Recital Hall in New York in 1965 (see Figure 2). Ono performed this piece herself at least six times, leaving plenty of room for differing interpretations. Cut Piece is seen as a milestone in the history of performance art as it emphasizes Ono’s radical approach to undiscussed issues of the time, in this instance, sexual assault/violence and the inferiority placed upon women within sexual contexts. She presented this work at a time when both men and women artists as well as the general public were not aware of feminist issues (Pfeiffer 31). Ono instructed her audience to engage in the exact behavior she was condemning; the act of “stripping her piece by piece resembled a rape” (Yoshimoto 99). Masterfully creating an inner conflict in each viewer, Cut Piece demanded action from the audience, granting Ono an unconventional passive role as a performer. The reversal sparked a myriad of unexpected responses and tension within the audience. Some members felt desire, others repulsion. Some experienced surprisingly violent urges, others calm restraint. Regardless of the response, Ono remained still, stoic, and controlled. It was if as she was “a mirror reflecting the feelings of the audience members; through watching the performance, the audience discovered voyeurism or violence within itself” (Yoshimoto 100).

Perhaps it was Ono’s vulnerability that allowed for such dynamic audience reactions. She released her mind and body into their hands, an action that overwhelms humanity. Even as she sacrificed herself to strangers, encouraging violent acts to be forced upon her, Ono maintained a nonviolent attitude, indicating her commitment to peace. She was way ahead of her time in giving acute visual form to women’s issues (The New York Times).

In 1972, Ono appeared on stage during Chuck Berry and John Lennon’s live duet performance of “Memphis, Tennessee.” In addition to helplessly drumming to the beat, Ono provides some “unwelcome discordant backing vocals” (see Figure 3) while Lennon tries to enjoy an exciting collaboration with his rock and roll hero, Chuck Berry. Ono’s bizarre and completely unwarranted contribution leaves the viewer (and likely all the band members on stage) confused, alarmed, and even annoyed. Many consider Ono’s act a fail, arguing that Lennon and Berry’s duet was destroyed by her absurd intrusion.

This concert was just one instance of many that generated hate and disapproval. A 1970 Esquire magazine article mocked Ono’s accent calling her “John Rennon’s Most Excrusive Gloupie.” Fans of Lennon would call Ono a “’nip,’ ‘Jap,’ ‘Chink,’ and other insulting names, insisting that she should get back to her own country. To make matters worse, Ono has long been blamed for pulling Lennon away from his bandmates and ultimately breaking up the beloved Beatles just a year after Ono and Lennon married (NBC News). Naturally, after Lennon died in 1980, his bandmates became more understanding of Ono’s artistry, but this may be solely because she inherited Lennon’s brand. The irony is that society looked down on Ono for quite some time only to eventually bow down to her.

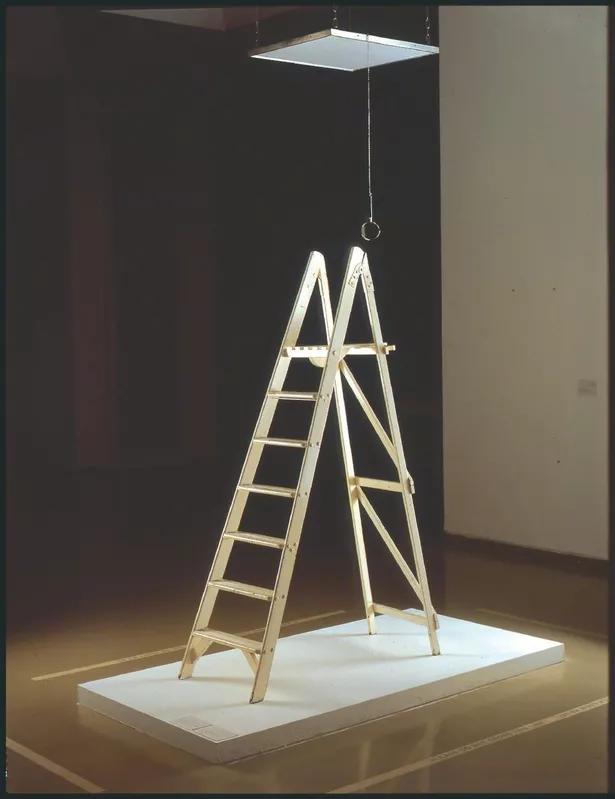

In 2013, the Schirn Kunsthalle Frankfurt presented Europe’s most comprehensive retrospective of Yoko Ono’s work titled Yoko Ono: Half-A-Wind Show: A Retrospective. First shown at Ono’s 1966 Indica Gallery show in London, Ceiling Painting, Yes Painting (see Figure 4) served as an early example of Ono’s interactive work. Its installation would be incomplete without its accompanying instructions: “Climb up a ladder. Look at the painting on the ceiling with a magnifying glass, and find the word ‘YES.’ ” The viewer is invited (in his or her mind) to climb to the top of a white ladder, where a magnifying glass, attached by a chain, hangs from a frame on the ceiling. The viewer uses the reading glass to discover a block-letter “instruction” beneath the framed sheet of glass: it says “YES” (Pfeiffer 70). Ono’s idea of instructing the viewer to perform an action in their mind suggests that achieving Ono’s objective always consisted of multiple requirements.

By 2015, the Museum of Modern Art presented its first (official) exhibition dedicated exclusively to Yoko Ono’s works titled “Yoko Ono: One Woman Show, 1960-1971.” The exhibition explored the many issues Ono confronted such as gender, class, and cultural identity all through the lens of her bold commitment to promoting world peace. Featuring 125 of her early objects, works on paper, installations, performances, audio recordings, and films, and rarely seen archival materials, the exhibition sought to display Ono’s “infiltration” of the public realm throughout her career. This show was based on Ono’s unofficial MoMA debut in late 1971 when she created her own “one-woman show,” titled Museum of Modern [F]art. However, when visitors arrived at the “exhibition” there was little evidence of her work. According to a sign outside the entrance, Ono had “released flies on the Museum grounds, and the public was invited to track them as they dispersed across the city” (The Museum of Modern Art). Over 40 years later, MoMA’s Yoko Ono: One Woman Show, 1960–1971 surveyed the decisive decade that led up to Ono’s unauthorized 1971 exhibition at MoMA, bringing together approximately 125 of her early objects, works on paper, installations, performances, audio recordings, and films, alongside rarely seen archival materials.

One of the works featured in the exhibition was Ono’s Apple: a green apple sitting on a plexiglass pedestal with a plaque reading “APPLE” (see Figure 5). This piece was first exhibited in a London gallery in 1966. It was at this exhibition that John Lennon met Ono for the first time. Ono recounts their meeting: “And then he saw the apple. You know, he didn’t say anything. He just grabbed it and had a bite in it. Apple was a fresh apple on an installation like this. And he just grabbed it and bit it and looked at me like, you know, ‘There!’ you know? I was so furious, I didn’t know what to say. And it all showed in my face: How dare this person, you know, mess around with my work? So he just said, ‘I’m sorry,’ and just put it on the stand again” (MoMA).

Although Ono was shocked by Lennon’s instinct to bite the tempting apple, it seems likely that any visitor would share the same instinct. And perhaps this is why the work feels pointless and rather redundant. Is it really art? Is a banana taped to the wall art? Is fruit art? Ono uses her fame and growing artistic influence to create something out of nothing. All it takes is the name of an artist to validate an object’s definition as art.

As seen in some of the works presented in this essay, Yoko Ono’s art is not always easy to follow, but she never intended it to be obvious. Her art is based on ideas and verbal instructions for actions that are either “utopian or actually performable.” A lot of her work is left in a state of “almost” or “perhaps” which oftentimes left viewers confused or unimpressed (Pfeiffer 23). Ono did not have the pleasure of her audience in mind when creating work. Even though her artistic creativity was overshadowed by her background as a Japanese woman and by the celebrity status brought on by her marriage to Lennon, Ono used both identities to her advantage (Yoshimoto 114). She stands firm in her individuality: “Yes, I’m a witch, I’m a bitch, I don’t care what you say. My voice is real. My voice speaks truth. I don’t fit your ways” (Japan Today).

Bibliography

Concannon, Kevin. “Ono, Yoko.” Grove Art Online, 2014.

Isozaki, Arata., and David B. Stewart. Japan-Ness in Architecture. Cambridge, Mass: MIT Press,

2006.

McNeill, David. “Yoko Ono Sounds Off.” Japan Today, Feb 7, 2009.

Menand, Louis. “Yoko Ono’s Art of Defiance.” The New Yorker, June 13, 2022.

Pfeiffer, Ingrid, and Max Hollein. Yoko Ono : Half-a-Wind Show : A Retrospective. Frankfurt am

Main: Schirn Kunsthalle Frankfurt, 2013.

Windolf, Jim. “Yoko Ono at 90.” The New York Times, Feb 20, 2023.

Yam, Kimmy. “Yoko Ono Was Called ‘Dragon Lady,’ Blamed for Beatles Breakup. Now, Her

Legacy Is Re-Examined.” NBC Universal News Group, Dec 21, 2021.

“Yoko Ono: One Woman Show, 1960–1971.” The Museum of Modern Art, 2015.

Yoshimoto, Midori. Into Performance : Japanese Women Artists in New York. New Brunswick,

N.J: Rutgers University Press, 2005.