https://library.artstor.org/asset/ARTSTOR_103_41822003375159

The impetus behind this project stems from an architectural/artistic interest of mine in the evolving relationship between built and natural spaces, a fascination that has only deepened since seeing the ways in which Japanese architecture is built within natural spaces without overtaking them. I noticed throughout class lectures and readings that many architectural structures were deeply site-specific, and I feel the temple complex of Murōji is a testament to the great reverence many Japanese architectural spaces take to their surrounding natural environments. This is a means of interaction, a sort of implied reciprocity and mutuality between human and natural world, perhaps even to suggest it is not such a binary.

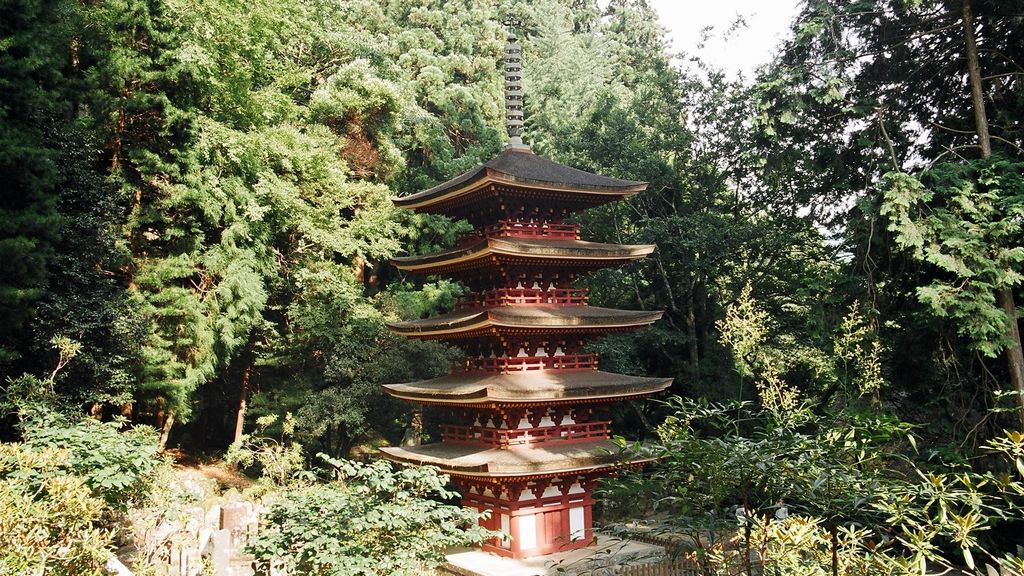

To examine this, I chose the Murōji temple, specifically the five-storied pagoda, resting at the base of Mt. Murō and built in the late 8th century. The mountain stretches across Uda district of the southern Nara prefecture. Most notably, the built environment at Murōji was determined physically and spiritually by its natural landscape.

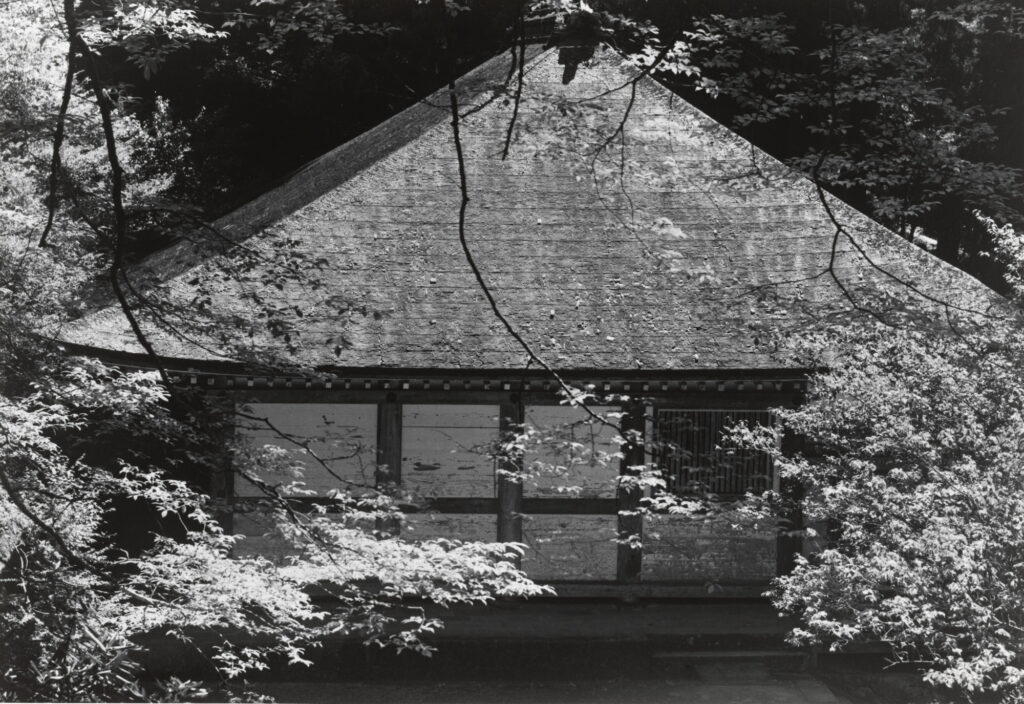

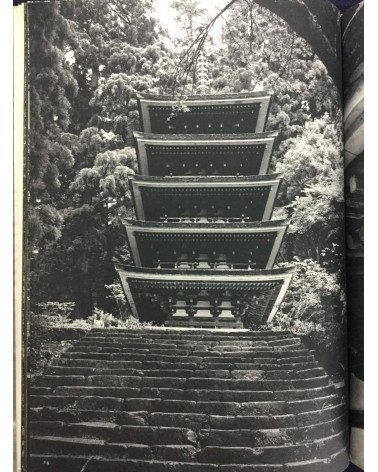

Ken Domon, a mid nineteenth century Japanese photographer, sought to capture the beauty of Murōji and publish it alongside informational text in one of the first and most notable works covering the temple: The Muro-ji, an eighth century Japanese Temple: Its Art and History (1954). Ken Domon, committed to capturing the resurgence of Zen Buddhism, is an important layer in how Murō-ji’s “Japan-ness” was externalized and publicized. Domon sought to embody the spirit of Japanese architecture in his photos. He uses his photography book as an opportunity to guide readers through the experience of walking the temple grounds, but jumps between buildings and structures to disorient the experience. This is an attempt to render the narrative of Murō-ji a more open-ended one, where readers can re-enact and imagine how the Muroji structures and statues were built and placed, and engaged with the spiritual nature of Japan-ness on a deeper level.

During the preceding Asuka and Nara periods, Japanese emperors of the state were centralizing their power in the city capital and the architecture reflected this. By the early Heian period, a new capital was established in Heian-kyo – modern day Kyoto – and was then referred to as “The Capital of Peace and Tranquility.” The temple represents a transition out of Asuka and Nara periods and into an Early Heian style with a move to mountainous regions as sites for spiritual endeavors.

By the early ninth century into the tenth century, Murōji became the destination for Buddhist pilgrimages because of its cultural and spiritual importance; it is said that a dragon spirit resides at the temple that once cured a Japanese prince who could otherwise not be cured. Because of the symbolic association between dragons and rainwater in Japanese, Korean, and Chinese traditions, Murōji became the site for rainmaking ceremonies specifically, and where parishioners and monks came to meditate on the land to restore its natural harmony. In her book, Murōji: Rearranging Art and History at a Japanese Buddhist Temple, author Sherry D. Fowler suggest that Mt. Murō was considered an “efficacious place for rain prayers because a dragon with the ability to control rain was believed to reside on the mountain” (30). Additionally, Murōji placed an emphasis on fecundity/fertility that was closely intertwined with its varying Buddhist ideologies; for instance, under an altar in its Maitreya hall are 37,000 miniature stupas each with a rice grain inside.

These Buddhist pilgrimages occurred at Mount Murō because of its recognized ancient, sacred quality, as well as the mountain being rendered a sort of mysterious area of nonactivity, due to it being at the center of inactive volcanoes. Murōji was home to a multitude of factions of Buddhist practice and thought due to the influx of monks from various schools, such as Kofukuji, Shingon, and Tendai. Uniquely, Murōji therefore showcased a plurality of Buddhist schools of thought. The temple also is widely known to have accepted women at the time – garnering the nickname “women’s koyasan” – where in many socio-cultural sectors of Japanese society, this was rare. Murōji being a nexus of spiritual ideas contrasts with the universality and singularity of its natural setting, evidence to the belief that Mt. Murō is recognized first and foremost as a natural setting that is to be revered.

The Murōji temple is a cluster of ancient buildings in the dense woodland forest of Mt. Murō, and each building in the temple complex is spread out with considerable distance, to allow for not only a natural enclave but also personal intimacy within and along each architectural space. Monks and parishioners moved from one temple structure to the next, they maintained the importance of its mountainous setting. Perhaps its most notable structure is its five-storied pagoda, which is the smallest temple pagoda of Japan as well as one of the oldest pagodas that still stands in Japan.

The temple complex was arranged according to the topography of the mountain. Murōji’s “Kondo,” or Main Hall, is in simple lecture hall style and was built in the mid to late ninth century. The topography is an essential element for the layout of Murōji and the ways in which it is site-specific. Mount Murō has several peaks – the highest peak standing at about 500 meters – and sits at the center of a cluster of inactive volcanoes. Because of this, the rain accumulates on the summits and trickles down the mountain to create rivers of water that are viewed as sacred and central to the founding of Muroji as a rainmaking site. There are several caves believed to be the openings of the dragon spirit (“King Zentatsu”) on Mt. Murō. Also imbuing the mountain landscape with sacred powers are its buried relics. According to legend, Shingon master Kūkai brought back relics from China at the end of the ninth century and buried them on the mountain. These stories point to the spiritual power and undergird the Shingon lineage of Mt. Murō.

The layout of the temple – thus, walking its grounds – is a spiritual endeavor in itself. To reach the main building of Murōji, one must walk up approximately 300 flights of stairs. Each temple structure is relatively spread out, and requires more stone steps to reach. The physical experience of walking Murōji is a testament to its Japan-ness, where the spiritual essence of Japan is not only manifested in its framed art and designated architectural structures, but also one’s engagement with its art and through it, how it is embodied and maintained in a natural space.

The Main Hall features a masonry terrace using a “kake-zukuri” overhang construction style as many architectural features at Murōji accommodate to steep mountains.

https://library.artstor.org/asset/ACOLUMBIAARTIG_10313270719

Murōji’s five-storied pagoda is one of the purest expressions of how the temple complex as a whole demonstrates a deeply intimate relationship with its natural setting, and reaches into larger notions of place-based architecture as an arguably central tenant of “Japan-ness.”

Though it is contested and there is no historical record for the true meaning of the pagoda’s five stories, many suggest the number is symbolically derived from the five wisdom buddhas who spread golden light throughout the temple and are seated within the pagoda. The pagoda was built with a flexible construction technique that allowed it to respond to strong natural forces. Its roof features a unique hinoki bark thatching structure: a labor-intensive style that allows one to remove bark from the Hindi Cypress tree in such a way that will preserve the tree and thus allow the forest to continue to grow. Though this rare roofing style requires attention every twenty or so years, it is a testament to how Murōji was built according to its surrounding environmental conditions and with an effort to preserve it.

Murōji as an architectural concept explores how Japan-ness as a culturally-informed idea is translated into Japanese architectural traditions and innovations. The details in the Murōji temple – nature-based motifs, deliberate and careful construction, the story of its founding – are evidence to a Japanese architecture of reciprocity within nature, and proof that its Mt. Murō is regarded as sacred.

Bibliography

Domon, Ken, and Momoo. Kitagawa. The Muro-Ji, an Eighth Century Japanese Temple : Its Art and History. Tokyo: Bijutsu Shuppan-Sha, 1954.

Fowler, Sherry D. Murōji : Rearranging Art and History at a Japanese Buddhist Temple. Honolulu, HI: University of Hawaiʻi Press, 2005.

Fowler, Sherry. “In Search of the Dragon: Mt. Murō’s Sacred Topography.” Japanese Journal of Religious Studies, vol. 24, no. 1/2, 1997, pp. 145–61. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/30234155.

Edward Kidder, The Art of Japan (Century, 1985)

Wada, Stephanie S. “Murōji.” Grove Art Online. . Oxford University Press. Date of access 15 May. 2023, https://www.oxfordartonline.com/groveart/view/10.1093/gao/9781884446054.001.0001/oao-9781884446054-e-7000060487

Abiko, Bonnie. “Heian period.” Grove Art Online. . Oxford University Press. Date of access 15 May. 2023, <https://www.oxfordartonline.com/groveart/view/10.1093/gao/9781884446054.001.0001/oao-9781884446054-e-7000037212>