Overview

What is a Japanese dragon? What makes a Japanese dragon different from other Eastern dragons? Is there truly a difference? If so, how? To explore the characteristics of the Japanese dragon is to determine what influence Japan has had, and what Japan is and needs in its legends.

Dragons have been a passionate interest of mine from a young age. Eastern dragons emerged as integral figures, both as artistic inspiration and for meditative and therapeutic exercises. In stark contrast to the fire-breathing draconic antagonists of western folklore, eastern dragons are often depicted as contrasting, benevolent water deities. A chance to explore the history and development of these dramatically different legends was simply too great to ignore. My research followed the progression of the Japanese dragon from Shintoism to Buddhism, their classifications and divergences from the Chinese dragon, their presence in Japanese mythologies, and other draconic influences found in Japanese culture and architecture.

Background

The work of Visser (1913) and Daniels (1960) were pivotal to the tracing of the Japanese dragon’s development. The Japanese dragon is an old figure, and its form and purpose has been subject to change over time. As a result, the span of this research has been extensive. Predating the arrival of Buddhist traditions and beliefs, the Japanese dragon was synonymous with great serpents, and it is theorized the native, original term for dragons was the “tatsu.” Reference to this term and its original meaning still exist in the Japanese language today, like the word for whirlwind – “tatsu-maki,” or “dragon-roll,” meant to denote a dragon rising into the sky in a waterspout. Shinto tradition considered these beings river and water spirits, with control of rain and drought, found both inland and the sea. A subsection of Shintoism called Ryūjin shinkō, or “dragon god faith,” worshiped dragons as deities, and remnants of this practice remain today in sacred dragon shrines. The arrival of Buddhism brought with it a surge of dragon lore. From the wish-granting, serpentine naga of India, to the four-limbed imperial weather deities of China, the Japanese dragon was transformed into a mix of all three traditions, taking on the properties of storms, water, and wind, and the shape seen in Japanese art today. Even the modern Japanese term for dragons, “ryu,” is believed to be a synthesis of the Chinese characters for “lung,” and the Japanese “tatsu.” Dragons remain important in Buddhist tradition, with Buddhist temples often sharing myths of dragons residing in nearby rivers and ponds. The Sensō-ji temple of Japan even holds a biannual gold dragon dance. Beyond Shintoism and Buddhism, Japanese artists themselves strove to make their dragons distinct, and adopted the practice of defining the Japanese dragon by its toes. While this practice is not definitive due to the three-toed dragon having its roots in ancient China, it can be a good indicator regardless. Figure 1 shows the traditional traits of a Japanese dragon, contrasted with Figure 2 which, while also demonstrating Japanese dragon traits, shows the difficulty in delineating between the Japanese and Chinese dragon.

Classification and Divergence

Interestingly, classification of the Japanese dragon, as found in the Wakahara et al. (1897) version of the Japanese Buddhist Encyclopedia, mirrors that of the Chinese dragon, with a few additions. Like the Chinese dragon, the Japanese dragon, at least in its Buddhist traditions, progresses through stages as it ages and gains in power. The dragon begins as a water snake. After five hundred years, it gains scales and becomes a Kiao-lung, or scaled dragon. After a thousand years, it gains legs and becomes a Ch’i-lung, or hornless dragon. Another five hundred years, and it gains horns, becoming a K’iu-lung, or horned dragon. Finally, with another thousand years, it gains wings, ascending as a Ying-lung, or winged dragon. Interestingly, the Japanese edition gives name to the initial, water-snake stage where the Chinese do not, calling it a P’an-lung, or coiled dragon: a dragon that has yet to ascend to heaven. Wakahara et al. (1897) then divide the dragons into five further “classes,” based on their body shape: toad-dragons, horse-dragons, crow-dragons, fish-dragons, and snake-dragons. Of these five, the snake-dragon is named as the form that a dragon “ought” to have, and is considered the most auspicious.

Dragons in Mythology

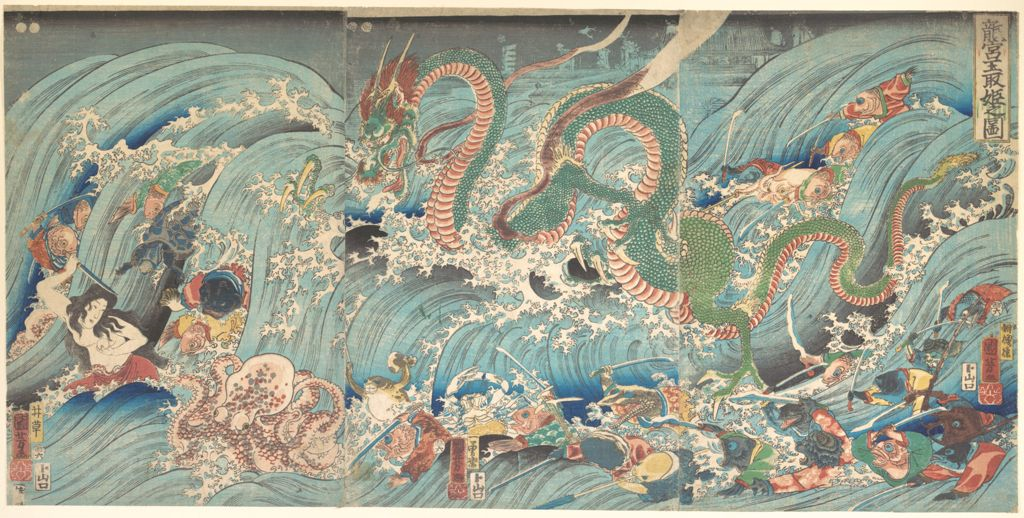

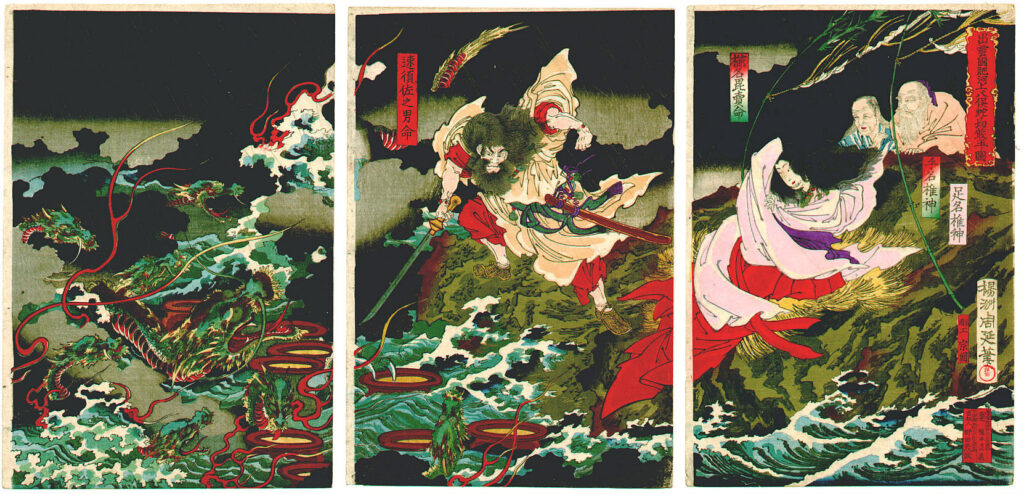

The Phillipi (1968)’s translation of the Kojiki, and Visser (1913) gave insight into the various mythological depictions of the Japanese dragon. Despite widely being considered benevolent, their role in stories are not so clear cut. One of the most prominent dragons of Japanese myth is Ryujin, also known as Watatsumi or Sagara. In the myth of Hoori, Ryujin is a benevolent figure who hospitably receives one of a pair of feuding brothers, letting Hoori stay in his palace for three years, offering the use of two tide gems to win his feud, and even letting him wed his daughter. But Ryujin is also the subject of tales of fear. One belief posits that should a storm suddenly arise around a ship at sea, it is that same dragon-king, coveting something onboard that ship. If the ship can throw the coveted object into the sea in time, the storm will abate, and the dragon will be satisfied. If not, the storm would only worsen. In the legend of Princess Tamatori, a gift to Emperor Fujiwara is sunk by a storm, and the wife of Fujiwara’s son braves the dragon palace to recover it. She steals the pearl and flees as the Ryujin and his watery minions rise in pursuit. While she successfully retrieves the pearl, she dies in the act. Figure 3 shows an illustration of this tale by Kuniyoshi. His depiction of the dragon-king is terrifying but also beautiful, encapsulating the idea of Ryujin, a dragon that can be kind and hospitable, or covetous and cruel as a force of nature. But not all Japanese dragons are even occasionally benevolent. One classic example is the Yamata-no-Orochi, a monstrous eight-headed and eight tailed dragon-serpent-god, who besieged the mortal realm and demanded a regular sacrifice of maidens. When Susano’o-no-Mikoto was exiled by his sister, the sun goddess Amaterasu, he witnessed a beautiful goddess next to be sacrificed. To save her, he plotted to defeat the serpent. Eight jars of divine sake were offered, one to each of the dragon-god’s eight heads. The Yamata-no-Orochi gorged itself until it lay in a drunken stupor, and Susano’o cut off its heads one by one. The Kusanagi sword was found in one of the dragon-god’s tails, and Susano’o presented it as a reconciliation gift to Amaterasu, and thus ascended back to the celestial realm. Today, the Kusanagi sword is one of the three national treasures of Japan kept by the imperial family. Figure 4, by Chikanobu, shows the dragon-serpent’s defeat and the clear malevolence of its maiden-eating, near western-style role.

Dragon Symbolism and Influence

The jewels often depicted as being held in a dragon’s claws, or being chased as if to be swallowed, also have their roots in different cultures. In India they are referred to as cintamani, a jewel that grants all desires, and feature as a prize to be won in many myths and fables. In China it has been theorized that they represent the moon, to be swallowed as the rain and clouds swallow the moon from sight. In Japan, they are thought to be tide gems, which cause the sea to ebb and flood, and are one of the primary treasures of Ryujin’s palace. In other words, as masters of the sea, the dragon guards its treasures (Visser, 1913).

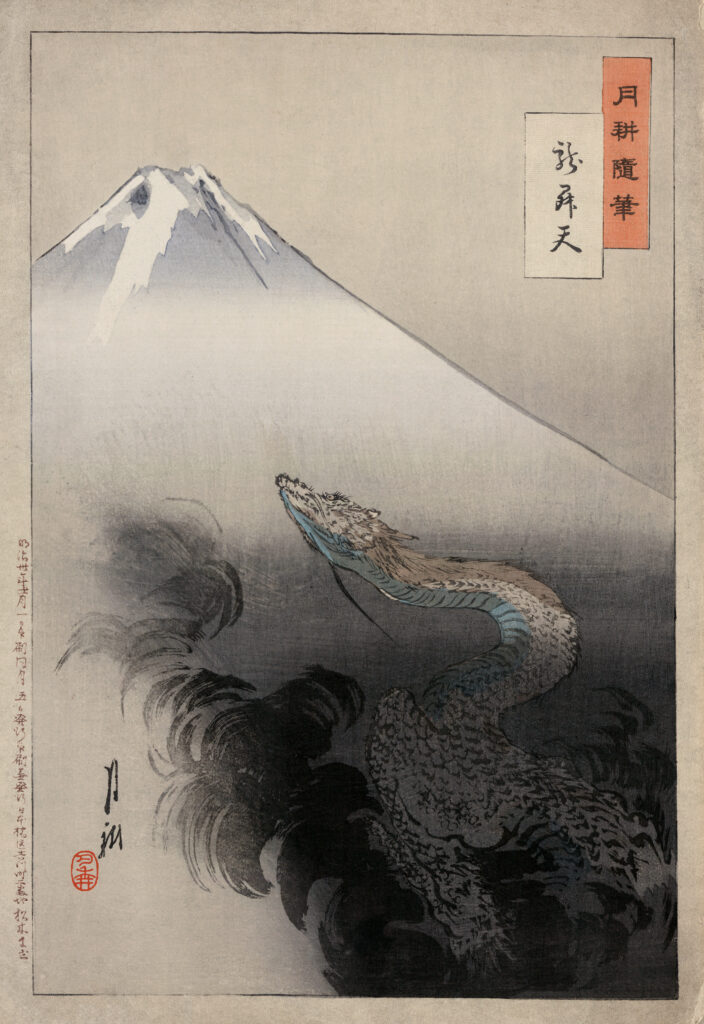

As found in the Shinto tradition, depictions of dragons in art and architecture are representative of good fortune. Particularly auspicious is the sighting of a dragon flying over Mt. Fuji, which was said to indicate a righteous reign, or, in modern times, success in career. Figure 5 depicts this saying, and demonstrates the dragon’s symbolic role in Japanese culture.

Conclusion

The dragon of Japan is multifaceted. It is at once very similar to the Chinese dragon, and often in art is hard to distinguish, but it also has been adapted into the Japanese identity. It is powerful, beautiful, and wise, and it is terrifying, covetous, and cruel. It is, more than anything else, tied to water – to the sea, to rivers, to rain. Its varied depictions mirror the role of water in Japanese culture. Japan is an island nation. Water is integral to Japanese life, and immensely important for trade and livelihood. Any being that can influence water is a source of boon and bane. Thus the benevolent rain-bringer and the terrifying force of nature are both the Japanese dragon.

Primary Textual Sources

The Dragon in China and Japan, by Visser (1913), is a comprehensive collection of the sources of dragon lore across India, China, and Japan. It is a collection of myths, rituals, ceremonies, traditions, symbolism, related or possibly related concepts, and accounts of dragons in these cultures. Despite being written by a western scholar, the account is generally objective, well corroborated, and positively regarded by peer review. This work is the primary source for this article.

Snake and Dragon Lore of Japan, by Daniels (1960) builds off the work of Visser with particular focus on the Japanese snake and dragon. This account approaches the interactions with the Japanese dragon, and the snakes often related to them, from a behavior angle, to build on the ideas and beliefs outlined by Visser (1913). Specifically, actions taken by people in superstitions, offerings, and art.

Visual Sources

Title: Matsuri Yatai Dragon

Creator: Katsushika Hokusai

Date: 1844

Size: 48.4” by 49.8”

Material: Ukiyo-e painting

Description: A 48.4” by 49.8” ukiyo-e painting with the description of “Dragon painting on the ceiling,” by Hokusai. A four-limbed, three-toed golden dragon is painted upon a rich red surface, surrounded by stylized blue and white waves. The dragon is intricately detailed, plated and spiny, with two horns, a pair of whiskers, and piercing eyes. This dragon’s eastern traits – precise toes, serpentine body, and association with water, are the focus of the painting.

Title: Dragon Bowl

Creator: Kurokawa Eishō

Date: 1895

Size: 5 ¾” x 11” x 6 ¼”

Material: Silver

Description: a round, silver bowl. Wrapped around its sides is a long, serpentine, ornately detailed Japanese dragon. The dragon appears fiercely glaring, with its three-toed claws bared. The dragon has a furred face and mane, whiskers, antlered horns, fish-style scales, three-toed claws, spines along its back, and a plumed tail. It appears fiercely glaring, with claws poised as if to strike, and wraps around the bowl so that its tail and outstretched foreclaw are parallel. The dragon’s three toes and the Japanese artist suggest it is a Japanese dragon, but even then it is difficult to be certain, and this conundrum demonstrates the synthesis of many of the modern Japanese dragon’s traits with the Chinese dragon.

Title: Ryugu Tamatori Hime no su / Recovering the Stolen Jewel from the Palace of the Dragon King.

Creator: Utagawa Kuniyoshi

Date: 1853

Size: 15” by 30”

Material: Woodblock print; ink and color

Description: An approximately 15” by 30” triptych of polychrome woodblock prints; ink and color on paper. The print depicts Princess Tamatori fleeing with the recovered pearl in hand, as the dragon king (Ryujin/Watatsumi/Sagara) and his horde of monstrous fish, octopi, crabs, turtles and toads rise from the waves in pursuit. The dragon king in this image is not unduly grotesque, but rather massive, magnificent, and terrifying, like any natural disaster, and lends itself to the dragon’s role in Japanese culture as benevolent and wrathful in turn.

Title: Yamata no Orochi

Creator: Toyohara Chikanobu

Date: circa 1870s

Size: 15” by 30”

Material: Woodblock print

Description: An approximately 15” by 30” woodblock print, with the description of “Susano-o-no-mikoto kills the eight headed dragon-serpent to rescue Princess Kushinada of Izumo province. He prepared eight large barrels of sake. When the monster got drunk, he cut off the eight heads one by one.” This legendary serpent-dragon has many similarities to the monstrous Western dragon, as a maiden-eating antagonist.

Title: Ryū Shō Ten

Creator: Ogata Gekko

Date: 1897

Size: 14.8” x 9.8”

Material: Woodcut; color

Description: An approximately 14.8” by 9.8” woodblock print, with the description of “Print shows a serpent or dragon ascending on a cloud to the top of a mountain.” This description, and the translation of the title – “dragon rising to the heavens,” illustrate the depiction of a dragon ascending Mt. Fuji. This association is thought to be an expression of good luck and career success, and demonstrates the symbolism of the Japanese dragon in turns of phrase and culture.

Bibliography

Daniels, F. J. “Snake and Dragon Lore of Japan.” Folklore 71, no. 3 (1960): 145–64. http://www.jstor.org/stable/1258001.

Phillipi, Donald L. 1968. Kojiki. Tokyo: University of Tokyo Press.

Visser, Marinus Willem de. 1913. The Dragon in China and Japan. Amsterdam: J. Müller.

Wakahara, Keikyō., Kinpō Nakagawa, and Michiyuki Minokata. 1897. Bukkyō Iroha Jiten. Nagoya: Kichūdō Shoten, 3018.

Images

Katsushika Hokusai (Japanese, 1760–1849), 1844. Matsuri Yatai Dragon. Painting: ukiyo-e. Place: Hokusai Museum, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Hokusai_Dragon.jpg.

Kurokawa Eishō (Japanese, 1854-1917). 1895. Dragon Bowl. Bowl, Metalwork. Place: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, https://www.metmuseum.org/. https://library.artstor.org/asset/27269308.

Ogata Gekko (1859-1920), 1897. Ryū Shō Ten. Place: Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division, https://loc.gov/pictures/resource/jpd.01559/

Toyohara Chikanobu (Japanese, 1838–1912), circa 1870s. Yamata No Orochi. Place: Wikipedia. October 4, 2023. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Yamata_no_Orochi#/media/File:YamataNoOrochi.jpg.

Utagawa Kuniyoshi (Japanese, 1797-1861). 1853. Ryugu Tamatori Hime no su / Recovering the Stolen Jewel from the Palace of the Dragon King. Print, Prints. Place: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, https://www.metmuseum.org/. https://library.artstor.org/asset/SS7731421_7731421_11753894.