Overview

My goal for this project and my research was to provide an outlook into an era of art that evolved the idea of “Japan-ness”. My original research question dove into the evolution of modernism within Japan, from its origin in response to the destruction of the Great Kanto Earthquake, to its eventual halt as a result of the destruction of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. Within the research for this initial project, I found an extensive catalog of images and history, outlining the evolution of modernism through literature, fashion, and its eventual change in Japanese Architecture. In the context of Japanese literature, I spoke mainly about the children’s magazine Komodo No Kuni, which featured many different pieces of humorous and playful art aimed at audiences of children. This magazine strongly reinforced the ideas of modernism in its early stages, depicting children in the latest fashion, as well as using modern art techniques such as edgy geometric shapes with rigid shadows. The evolution of fashion with modernism reflected these ideas of geometric and rigid shapes, leading to a new idea of fashion within Japanese society. These new ideas of fashion went beyond these artistic values, actually changing the perception of gender roles within 20th-century Japan. Within my midterm project, I briefly talked about how the destruction of Hiroshima and Nagasaki put a hold on the modernism movement and how it later emerged through the form of architecture. For the expansion of this project, I decided to dive deeper into this resurgence of modernism and researched the post-war architecture of Metabolism within Japan. My research led me to discover an extensive catalog of visual examples as well as the history of the Metabolist movement. The origins of modernism, its implications on art and fashion, and the resurgence of modernism through metabolism architecture give an extensive view into the revolutionary concept of Japanese Modernism.

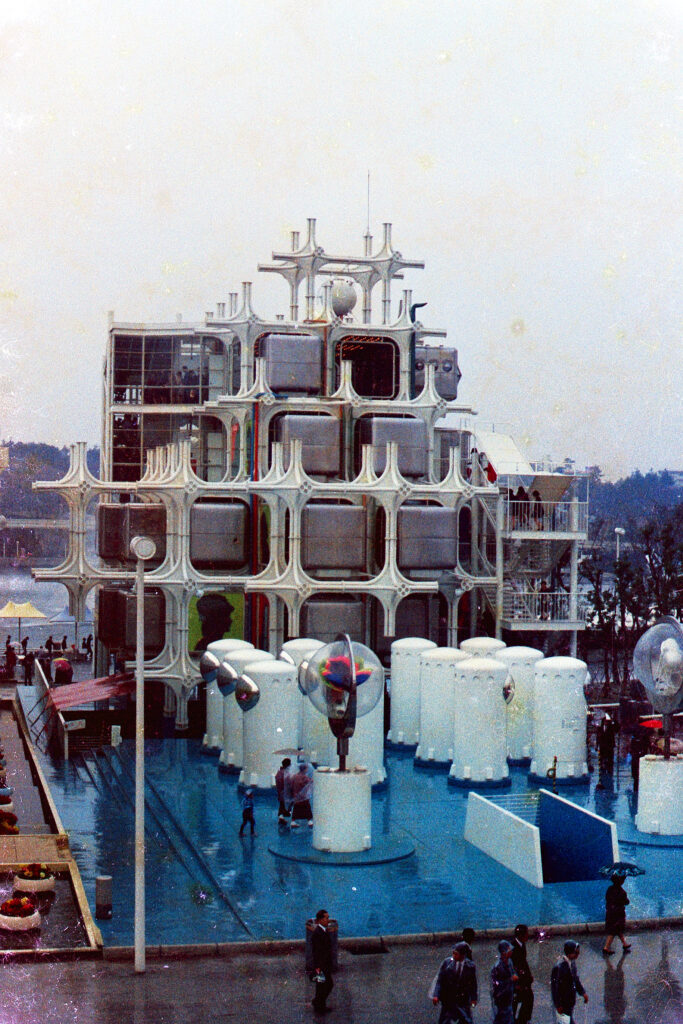

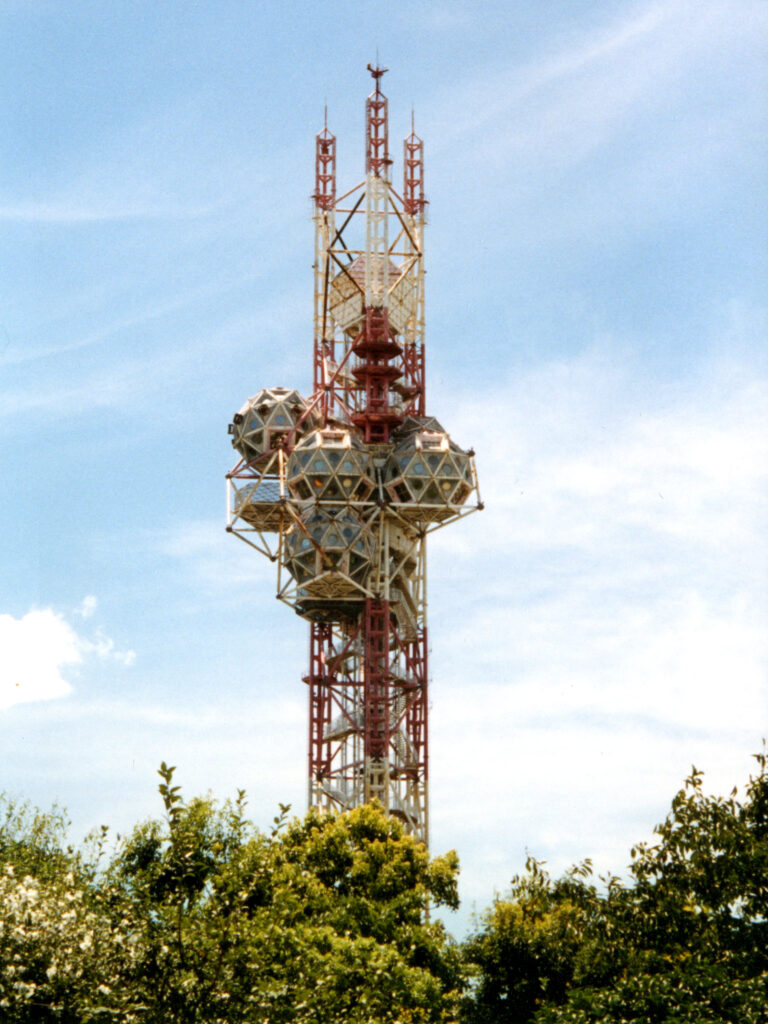

Visual sources used within my midterm topics give a view into these new geometric and rigid ideas of art so prominent within fashion as well as the new ideas of Art Deco that became prominent within advertisements for Japanese businesses and new constructions that began to pop up following the destruction of the Great Kanto Earthquake. Within examples of architecture, images from Osaka Expo ‘70 as well as images displaying the Nakagin Capsule tower give an insight into the modern idea of metabolism and its “organic” ideas of building.

Academic Sources used within my research gave deeper insight into the ideas of architecture within the minds of the individual metabolists, specifically Kisho Kurokawa. His ideas bring about the concepts of “ma” and “en” space, direct interpretations of Buddhist ideas. These Buddhist ideas helped me to connect the architect’s ideas with the origins of the word metabolism which overtones a spiritual perspective, close to the Buddhist concept of impermanence, which is the meaning of renewal, replacement, and regeneration.

Modernism Origins

Image 2: Shimbashi Station after Great Kanto earthquake, 1923 https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Shimbashi_Station_after_Great_Kanto_earthquake.JPG

Japanese modernist era was kickstarted by the destruction of the Great Kanto Earthquake (1923) and ended by the Pacific War (1942-1945). The Earthquake struck with a magnitude of 7.9 and what didn’t get destroyed by the earthquake was quickly taken by fires that spread through the city. Tokyo and Yokohama were burned to the ground by the end resulting in an estimated 140,000 deaths, and 700,000 people left homeless.

Tokyo’s reconstruction after its destruction led to a new era in art, one that emphasized the combination of Western culture and traditional Japanese culture. The construction of the subway specifically was Tokyo’s celebration of modernity. The Subway consisted of four stations and connected the recreation park and zoo area of Ueno with the temple, shopping, and river precinct of Asakusa. The futuristic novelty of riding the subway was so popular at the time that people would wait 2 hours for the 5-minute ride.

Evolution in Fashion and Gender Roles

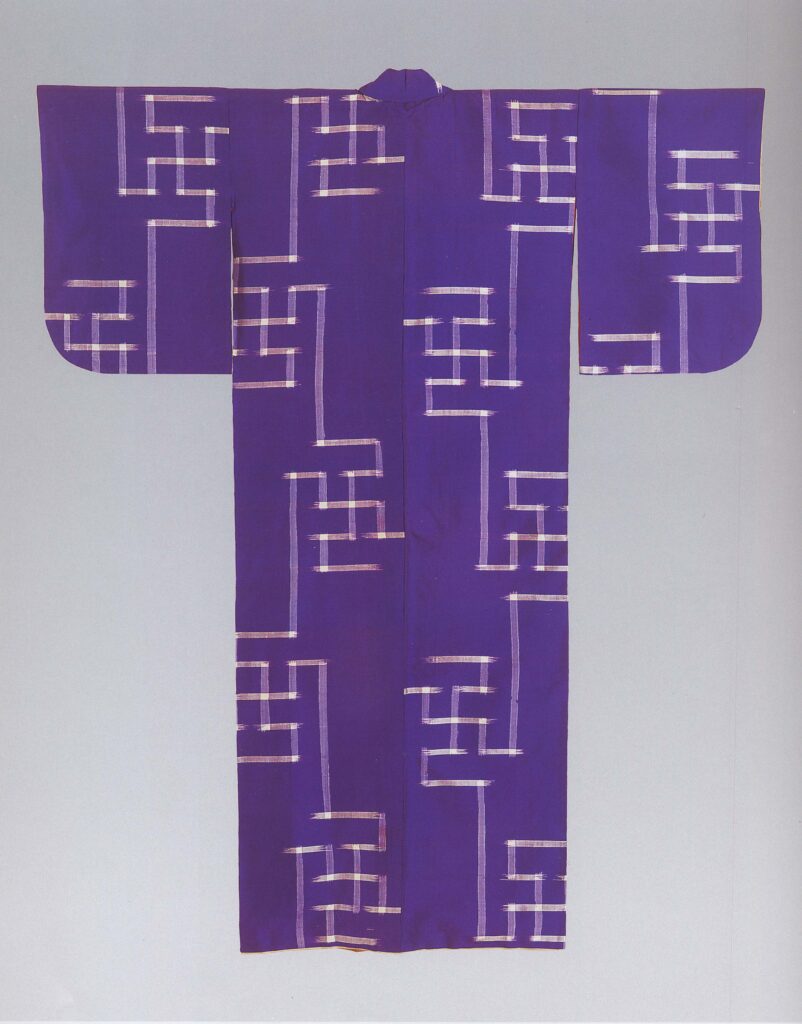

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Khalili_Collection_of_Kimono_K044.jpg

Image 2: Kimono for a Woman Motif: Skyscraper and city lights, between 1930 and 1940, machine-spun pongee silk (meisen), plain weave; stencil-printed warp and weft threads (heiyo-gasuri), Japan

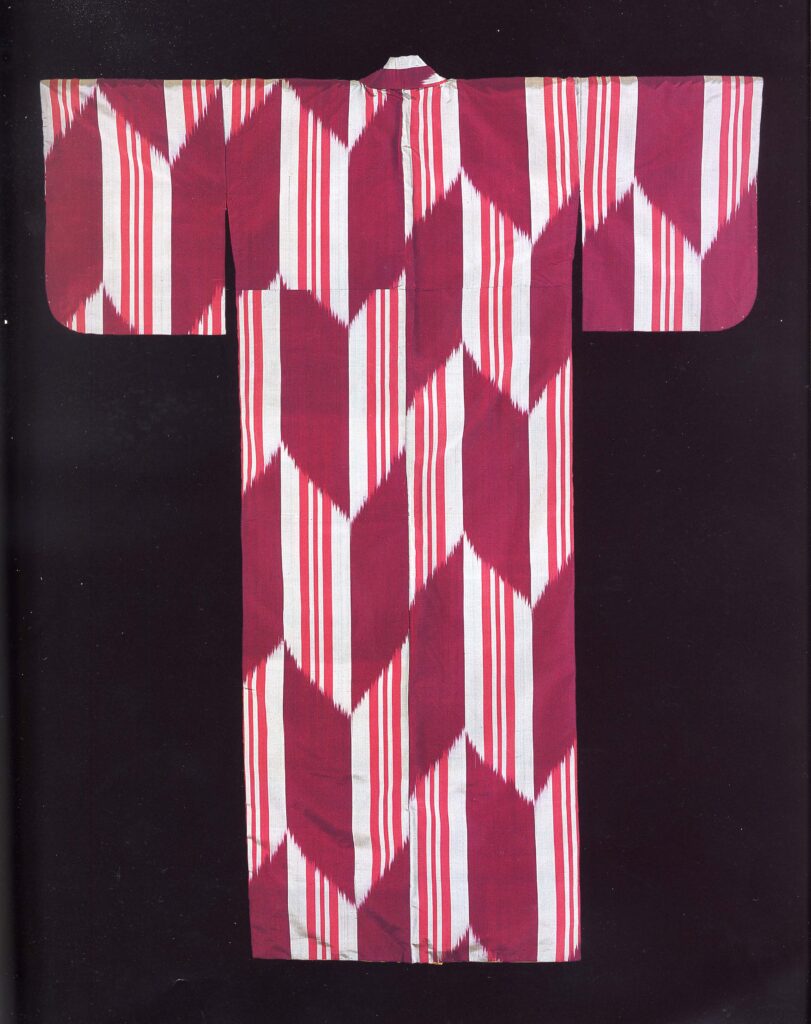

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Khalili_Collection_of_Kimono_K047.jpg

Image 3: Kimono for a Woman Motif: Arrow feathers, between 1920 and 1930, machine-spun pongee silk (meisen), plain weave; hand-tied selectively dyed warp threads (hogushi-gasuri), Japan https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Khalili_Collection_of_Kimono_K065.jpg

The Moga: Modern Girl

An acceptance of women in the workplace on top of an expanding consumer culture and modern modes of transport and recreation activities, created more jobs for women. These modern young women were considered the first generation of females in Asia to be liberated from traditional roles. Before this women would stay with family and help with home duties, or in rural families take over farm work. This opening of jobs and modern movement influenced many young women to leave their homes and head to the city. To some, these modern young women endangered traditional values, but they became an integral part of the Japanese economy. These women became avid consumers of fashion and chose to wear what they found fashionable and not what was seen as acceptable by their parents. Modern Women would wear Western-inspired clothing however would still wear traditional kimonos as a sentiment to Japanese culture. Kimonos featured vibrant geometric patterns to accompany the movement of modernity and these outfits included beaded handbags, picnic baskets, bakelite hairpins, parasols, headbands, and straw hats.

The Mobo: Modern Boy

The modern boy’s outer attire reflected the idea of a Japanese man’s dignified outer appearance, not indicating inner feelings and personality. Aspects of a mobo personality and interests could be revealed by the designs featured on the undergarments and outer coat worn over the kimono. Undergarments were covered with repeating patterns known as omoshirogara depicting cars, boats, and planes, vinyl records, and comic book characters. Coats were dark and plain but concealed intricate illustrations on the haura (interlining of coat). These designs were only revealed in personal settings or at parties and feature designs depicting basketball players, films, travel, and literature. A popular trend was depicting dramatic composition between traditional and modern Japan. Examples would be a scene of travelers on a road with a modern car making the same trip at fast speeds between Kyoto and Tokyo or Samurai on horseback with soldiers in tanks going across a battlefield.

Metabolist Architecture

The Metabolist movement emerged from the 1960 World Design Conference in Tokyo. It proposed that architecture should not only embrace new technologies and the enormous scales of the post-war period but also develop living, self-generating systems that could adapt over time. The movement was founded by a group of young architects with the core group including Kiyonori Kikutake, Kisho Kurokawa, Fumihiko Maki, and critic Noboru Kawazoe, all heavily influenced by their professor Kenzo Tange.

Connection to Buddhist Ideas

The Japanese word for metabolism is shinchintaisha (新陳代謝) which gives implications into a spiritual perspective, close to the Buddhist concept of impermanence, which is the meaning of renewal, replacement, and regeneration. From a biological point of view metabolism explains chemical reactions occurring in a living body, and how cells adapt and move to sustain life. Both these meanings acted as a frame of reference for the group’s designs and were a step closer to an architecture that was based on the natural circle of life

Kurokawa stressed the importance of undefined “in-between spaces” with a flexible meaning, such as verandahs or connecting rooms and hallways. He referred to these spaces as “en-space” and “ma-space”, two concepts taken from Japanese Buddhist thinking. “En” roughly translates to “chance” or “act of fate” while “ma” translates to an interval of time or space and has various meanings such as “buffer zone”, “boundary zone” or simply “room in an apartment”. Through these concepts, Kurokawa related his plazas and verandahs to these ancient Buddhist ideas.

Osaka World Expo ’70

Image 2: EXPO TOWER, 1970, Osaka, Japan https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:EXPO_TOWER.JPG

Expo 70 was the first world fair held in Japan and took place in Osaka prefecture in 1970. The expo exhibited countries’ accomplishments in terms of architecture, technologies, and economic development and also aimed to display new promises of technology to achieve peace and stability in the world. The master plan of the expo was commissioned to Kenzo Tange, a prominent figure in contemporary Japanese architecture and the former professor of the Metabolist group. With the help of another 12 architects including the Metabolist group, they designed and organized several elements for the fair.

The Symbol Zone, Osaka Expo ’70

As a central piece of the fair, the designers created a place where people from around the world could interact and socialize. They named it the Symbol Zone, a large plaza covered by a gigantic metal-framed roof. The Tower of Sun was placed in the middle of the plaza, made by Taro Okamoto, and was 70 meters tall. The tower served as a representation of the different faces of the sun during the seasons. Osaka Expo had more than 64 million attendees and 77 countries were invited to participate.

Nakagin Capsule Tower

Image 2: Capsule from Nakagin Capsule Tower Building, 6 October 2011 , Japan https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Capsule_from_Nakagin_Capsule_Tower_Building_DSCN0159.jpg

Image 3: Nakagin Capsule Tower, 3 January 2020, Japan https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:2018_Nakagin_Capsule_Tower_02_(1)_cropped2.jpg

Nakagin Capsule Tower was built in 1972 and designed by Kisho Kurokawa, this building is the closest thing that the metabolist group got to materializing their dreams. A tower made of 140 individual capsules plugged into two interconnected concrete cores. The capsules were designed with premade steel parts and made to be identical and compact. They measured 2.5 m y 4.0 m and fit all basic needs: a bathroom, air conditioning, storage, a bed, and a desk. The capsules were replaceable and had a 30-year life span and although the original idea was to replace the capsules with newer ones, it never ended up happening. In 2007, 80 percent of the residents of Tokyo voted in favor of replacing the building with a newer one. Kurokawa proposed a plan to renovate the building by replacing the old capsules with new ones but the plan ended after his death the same year, the building was eventually demolished last year in 2022. Before its demolition, the Nakagin Capsule Tower represented a memory of a utopia that never got the chance to be built and a rare physical example of experimental architecture from post-war Japan.

Bibliography

URBAN, FLORIAN. “Japanese ‘Occidentalism’ and the Emergence of Postmodern Architecture.” Journal of Architectural Education (1984-), vol. 65, no. 2, 2012, pp. 89–102. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/41820041.

LIN, ZHONGJIE. “Nakagin Capsule Tower Revisiting the Future of the Recent Past.” Journal of Architectural Education (1984-), vol. 65, no. 1, 2011, pp. 13–32. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/41319216.

Obradovic, Peter. “The Metabolism Movement – the Promised Tokyo.” Sabukaru, sabukaru, 10 Dec. 2021, sabukaru.online/articles/the-promised-tokyo.

Wang, Author: Tian. “A Brief History of Metabolism in Architecture.” Journal, 12 Apr. 2022, architizer.com/blog/inspiration/stories/history-of-metabolism/.

BUNTROCK, Dana. “METABOLISTS.” Metabolists, architecture-history.org/schools/METABOLISTS.html.

Lizzie Crook |12 April 2022 Leave a comment. “Demolition of Iconic Nakagin Capsule Tower Underway in Tokyo.” Dezeen, 2 Aug. 2022, www.dezeen.com/2022/04/12/nakagin-capsule-tower-demolition-begins-tokyo/.

Biography, architecture-history.org/architects/architects/KUROKAWA/biography.html.

“Kiyonori Kikutake.” Tokyo, projectarciutattokyo.wixsite.com/tokyo/kikutake.

Minner, Kelly. “Fumihiko Maki 2011 AIA Gold Medal Winner.” ArchDaily, ArchDaily, 10 Jan. 2011, www.archdaily.com/102633/fumihiko-maki-2011-aia-gold-medal-winner.

Japanese Modernism | NGV, www.ngv.vic.gov.au/exhibition/japanese-modernism/. Accessed 24 Oct. 2023.

Japanese Modernism: Between Earthquake and War | NGV, www.ngv.vic.gov.au/essay/japanese-modernism-between-earthquake-and-war/. Accessed 24 Oct. 2023.

Yamada, Chisaburο̂. “Japanese Modern Art.” Monumenta Nipponica, vol. 3, no. 2, 1940, pp. 567–78. JSTOR, https://doi.org/10.2307/2382598. Accessed 24 Oct. 2023.

Munsterberg, Hugo. “Tradition and Innovation in Modern Japanese Painting.” Art Journal, vol. 27, no. 2, 1967, pp. 151–55. JSTOR, https://doi.org/10.2307/775110. Accessed 24 Oct. 2023.

Perkins, Sam. “The Propaganda Kimonos Japan Kept Hidden from Outsiders.” Atlas Obscura, Atlas Obscura, 16 Nov. 2016, www.atlasobscura.com/articles/the-propaganda-kimonos-japan-kept-hidden-from-outsiders.

Brown, Phil. “The Relationship between Japanese and Modernist Architecture.” Medium, Design Culture & History, 26 Oct. 2017, medium.com/design-culture-history/the-relationship-between-japanese-and-modernist-architecture-7faef7e3b1ab.

Image Sources:

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Tower_of_the_Sun.jpg

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Khalili_Collection_of_Kimono_K044.jpg

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Khalili_Collection_of_Kimono_K047.jpg

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Khalili_Collection_of_Kimono_K065.jpg

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Shimbashi_Station_after_Great_Kanto_earthquake.JPG

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Ryounkaku_destruction_Great_Kanto_earthquake.jpg

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:2018_Nakagin_Capsule_Tower_02_cropped.jpg

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:2018_Nakagin_Capsule_Tower_02_(1)_cropped2.jpg

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Capsule_from_Nakagin_Capsule_Tower_Building_DSCN0159.jpg