Over the course of our exploration of the many different forms of Buddhist art, I found myself particularly interested in the motif of centrality, and more specifically how the motif could be observed over a wide range of works across vastly different mediums. For the purpose of this chapter, the motif of ‘centrality’ is defined as the outer details and components of a work of art revolving (literally and figuratively) around the center or central figure of the work.

In the case of the works highlighted in this chapter, the physical centrality of the Buddha or other religious/enlightened figures emphasizes the figurative centrality that the Buddha had in the lives of the people and cultures that this art comes from. This being the case, the motif of centrality in Buddhist art represents much more than a simple stylistic choice; it acts as a medium through which one’s deepest, most intimate spiritual desires are put on display. With this point in mind, we can hopefully form a better understanding of the role that concepts like religion, faith, and devotion served in these preexisting societies whose art we have access to now. Because the art of a given time period is often our best reference for forming a socially nuanced perspective on the customs and traditions of said period, it feels especially important to take the motifs and imagery seen repeated in art like the works shown in this chapter and interrogate them further.

Before getting into the body of this chapter, it feels important to first put forward a few ideas and concepts that allow for the featured works to be viewed together more coherently. Firstly, the motif of centrality has many inherent ties to the Mandala. If a mandala is meant to represent “the universe in its ideal form”, then that which lies at the center of the mandala represents the center of the universe – a point of origin and a point that radiates joy. The motif of the mandala, with this notion of centrality in mind, allows the central figure to ‘radiate outwards’ in a sense.

The Mandala holds profound significance in the Buddhist religion, representing a powerful symbol of spirituality and enlightenment. Derived from the Sanskrit word for “circle,” the Mandala is a geometric design that serves as a visual aid for meditation and a representation of the universe. Within the intricate patterns and symmetrical structure of a Mandala, Buddhist practitioners find a sacred space where they can focus their attention, calm their minds, and connect with the divine. The Mandala embodies the concept of impermanence and the interconnectedness of all things, reflecting the Buddhist teachings of unity, balance, and harmony. It is believed that through deep contemplation and visualization of the Mandala, one can attain spiritual awakening and gain insight into the true nature of reality. The Mandala thus acts as a portal to transcendence, offering a path towards enlightenment and inner transformation in the Buddhist tradition.

With basis in this concept of the Mandala, and what said concept stands for, the motif of centrality holds significant meaning in Buddhist art, serving as a visual representation of the core principles and philosophical concepts of the religion. In Buddhist art, the central figure, often a Buddha or bodhisattva, is depicted at the center of the composition, surrounded by other elements or beings. This positioning symbolizes the enlightened state and spiritual significance of the central figure, embodying their role as the focal point of wisdom, compassion, and guidance. The motif of centrality reinforces the teachings of Buddhism, emphasizing the importance of finding inner balance, harmony, and enlightenment within oneself. It reminds practitioners that true awakening comes from recognizing and cultivating the divine qualities that lie at the core of their being. Through the centrality motif, Buddhist art inspires devotees to seek their own inner center, aligning their thoughts, actions, and intentions with the noble path towards enlightenment.

Vajrabhairava with His Consort Vajravetali exudes a dynamic and intense energy. Vajrabhairava, a wrathful deity, stands at the center with a fierce countenance and a crown of skulls adorning his multiple heads. His body is adorned with wrathful ornaments, representing his power to subdue negative forces. The depiction of Vajravetali, his consort, adds a sense of balance and harmony to the composition. She is portrayed with a radiant and serene expression, symbolizing the union of wisdom and compassion. The artwork showcases the fiery passion and transformative energy of Vajrabhairava, while also emphasizing the importance of the feminine energy in the journey towards enlightenment. The intricate details and vibrant colors bring the artwork to life, captivating the viewer’s attention and evoking a sense of awe and reverence. Vajrabhairava with His Consort Vajravetali embodies the interplay between wrathful and peaceful aspects of enlightenment, inviting contemplation on the harmonious coexistence of seemingly contrasting qualities on the spiritual path

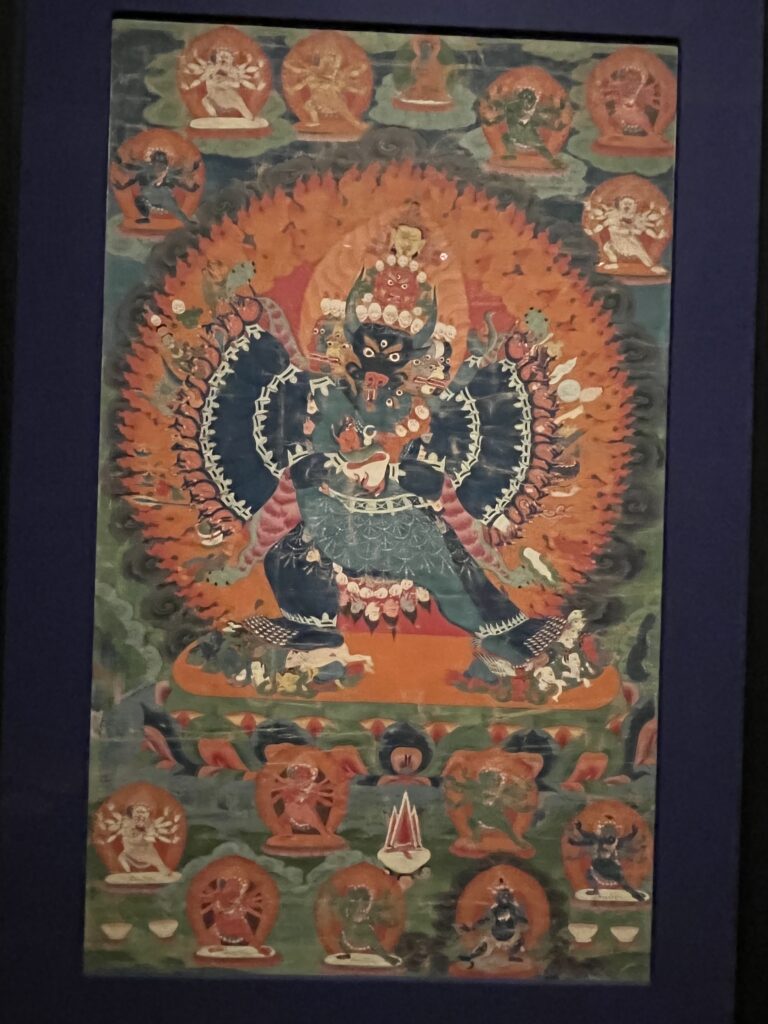

Like the previous work, this piece depicts the buddhist deity Vajrabhairava. The Mandala of Vajrabhairava is a visually captivating and intricate piece of art. At its center, a vividly colored and fierce deity, Vajrabhairava, stands surrounded by a blazing aureole of flames. Vajrabhairava is depicted with multiple heads, each adorned with a crown of skulls and emanating intense expressions. His body is adorned with various wrathful ornaments and symbols, symbolizing his powerful and transformative nature. The deity is depicted in a dynamic posture, trampling upon deities and animals, indicating his mastery over negative forces and obstacles. Surrounding the central figure, the mandala features a complex arrangement of concentric circles and geometric patterns, meticulously rendered in vibrant hues. The outermost circle consists of vivid lotus petals, symbolizing purity and spiritual growth. As the eye is drawn toward the center, intricate details and vibrant colors fill the composition, creating a sense of sacredness and divine energy. The Mandala of Vajrabhairava is not only a visually stunning piece of art but also a representation of the spiritual journey towards enlightenment and the fierce compassion inherent in Vajrabhairava’s transformative power.

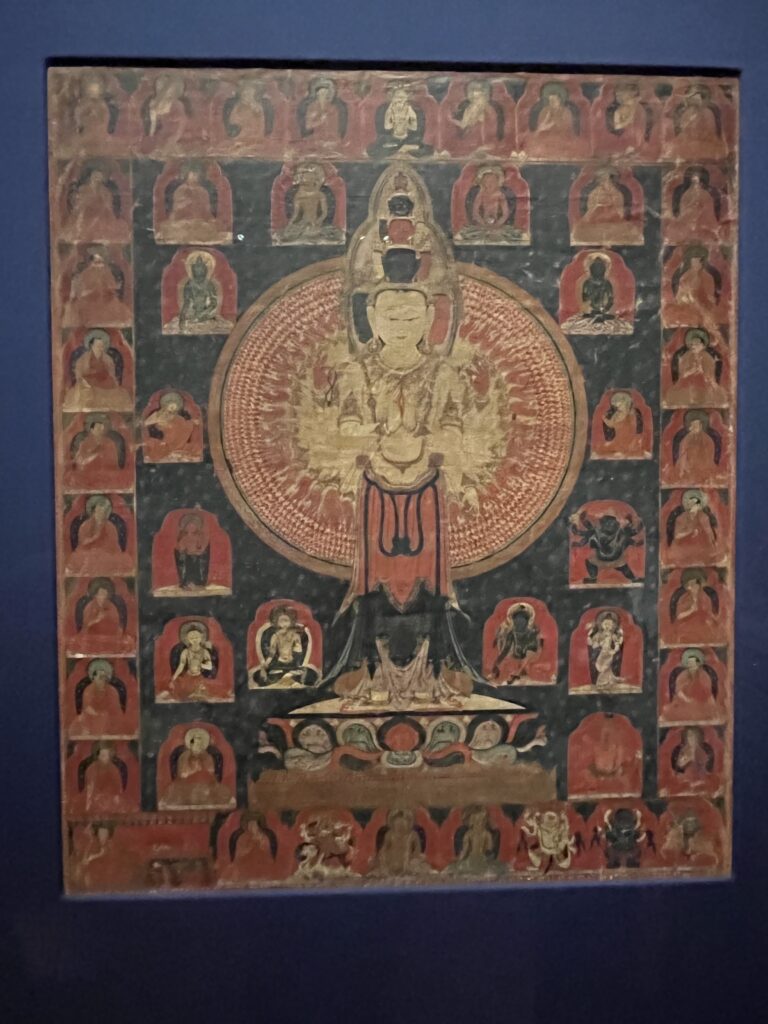

This piece, titled Thousand-Armed Chenresi, emanates a profound sense of compassion and spiritual depth. The central focus of the composition is the deity Chenresi, also known as Avalokiteshvara, depicted with a thousand arms radiating outward in perfect symmetry. Each arm is gracefully positioned, holding various symbolic objects such as lotus flowers, prayer beads, and implements of enlightenment. This depiction symbolizes Chenresi’s ability to extend compassionate assistance to countless beings simultaneously. The deity’s serene and loving expression reflects the boundless love and compassion that Chenresi embodies. The colors used in the artwork are often soft and ethereal, evoking a sense of tranquility and spiritual grace. Surrounding Chenresi, celestial beings, Buddhas, and bodhisattvas are often depicted, paying homage to the deity and highlighting the interconnectedness of all beings in the pursuit of enlightenment. The artwork captures the essence of Chenresi’s compassionate nature and serves as a visual reminder of the Buddhist teachings of empathy, mercy, and the pursuit of alleviating suffering in the world.

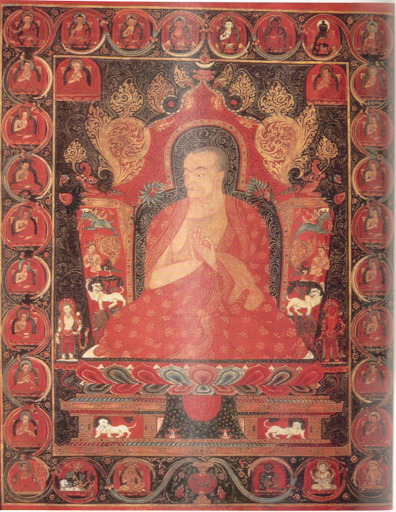

The teacher portrayed in this small tangka exemplifies the intrinsic qualities of Tibetan portraiture, showcasing a harmonious blend of sacred symbolism and human individuality. Seated in a manner reminiscent of the transcendent Buddha, the teacher assumes a dignified posture, radiating serenity and wisdom. With a hand posed in a gesture of teaching, he embodies the role of a spiritual guide and disseminator of profound knowledge. The teacher is enveloped within an intricately detailed mandorla, adorned with mythical creatures and intricate floral patterns. This mandorla serves as a symbolic gateway, signifying the transcendence of worldly limitations. However, it is the teacher’s stern countenance and intense, averted gaze that draw us into the realm of human emotion and devotion. Through these nuanced expressions, the portrait conveys not only a deep commitment to the spiritual path but also an unwavering dedication to personal growth and enlightenment. The blend of divine symbolism and human presence within this tangka invites viewers to contemplate the profound devotion and individual journey that lies at the heart of Buddhist spiritual practice.

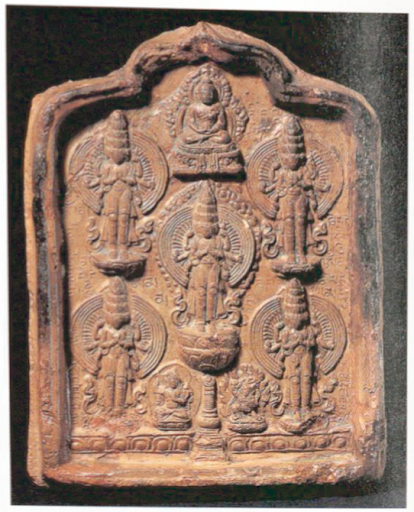

This clay tablet portrays the figure of Avalokiteshvara, the 11-headed and 1000-armed bodhisattva of compassion. The tablet features five distinct images of Avalokiteshvara strategically positioned to represent the four cardinal directions and the center, symbolizing the inclusive and all-encompassing nature of this compassionate deity. Each image is intricately detailed, capturing the essence of Avalokiteshvara’s divine presence and benevolent energy. Notably, chortens are depicted beneath the central figure, symbolizing the sacred Mount Meru, the mythical cosmic axis and center of the universe in Buddhist cosmology. This portrayal signifies the profound interconnectedness between Avalokiteshvara and the cosmic forces that shape existence. The clay tablet serves as a powerful visual reminder of the boundless compassion and transformative power that Avalokiteshvara embodies, inspiring viewers to cultivate compassion and seek enlightenment through their own spiritual journey.

From these works, we can see the diverse applicability that the motif of centrality has, and the various messages and emotions that the motif has the power to convey. More than just capturing this breadth of emotions, the motif of centrality within art acts as a proxy through which the viewer can be transported into the ‘world’ of the work of art itself. As was emphasized through this chapter’s focus on describing the intrinsic qualities of the featured works, the motif of centrality oftentimes makes the viewer feel something profound.

I find that this analysis of the motif of centrality in Buddhist art offers a profound answer to the question of “What is Asian Art?” by illustrating the essence of spiritual philosophy and cultural expression across Asian traditions. The centrality motif represents the interconnectedness of all things, capturing the fundamental teachings of unity, balance, and harmony found in many Asian philosophies. The motif encapsulates the spiritual and cultural values that permeate Asian art, emphasizing the significance of seeking inner balance and enlightenment within oneself. It portrays the interplay between the individual and the cosmos, offering a visual language to understand the interconnected nature of existence. The motif of centrality in Buddhist art not only encapsulates the essence of Asian art but also invites contemplation on the universal themes of spirituality, self-discovery, and the pursuit of transcendent wisdom that resonate across diverse Asian artistic traditions.

Reading List & Image Sources:

Robert Fisher, Art of Tibet (Thames & Hudson, 1997), chap. 2-3.

Benjamin Rowland, The Art of Central Asia (New York, 1974)

“Mandala of Vajrabhairava – Asian Art Museum .” Collections, collections.asianart.org/. Accessed 9 May 2023.

“Thousand-Armed Chenresi: Tibet.” The Metropolitan Museum of Art, www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/37799. Accessed 9 May 2023.

“Vajrabhairava with His Consort Vajravetali: Tibet.” The Metropolitan Museum of Art, www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/37834. Accessed 9 May 2023.