Marissa Paratore

The Goal of My Chapter

The goal of this chapter is to expand how we see Chinese landscape paintings, by learning how artists used visual motifs and spirituality to convey meaning in their art. Chinese landscape paintings also referred to as shan shui (“mountain-water”), are undoubtedly gorgeous but is there meaning behind the brush strokes or are they simply replications of nature’s beauty? When first viewing this style of art I was unsure of the answer to this question. These Chinese landscapes are incredibly different from landscape paintings made in the United States, but the unique terrain is not what differentiates them, it is the style. Unlike most Western art, color is uncommon in this genre of painting, specifically in older pieces. Instead, ink is desaturated with water to create endless shades of grey and black. These paintings amazed me with the amount of detail and dimension that could be captured without color. As an artist in the making myself, I prefer to work without color but have found it difficult to feel my art looked complete in its absence. Viewing these artworks I was inspired by how incredible these paintings could look, and how the artists managed to capture so much, so successfully, with such a limited palette.

Why these Images?

The paintings I chose all fall into the category of shan shui paintings; characterized by three basic elements: mountains, rivers, and often waterfalls. Mountains are the “heart” of a Chinese landscape painting. They are the center point of a vast landscape, jutting upward toward Heaven. Water sources such as river streams and waterfalls bring a sense of balance to the painting. These paintings focus on connecting the viewer to the world rather than accuracy. The exaggeration of the landscape draws the viewer in. When looking at these paintings as a whole one might only see the incredible scenery, but when looking closer at each painting, many tiny details are visible. Each painting includes humans and human structures/vessels within the terrain. Without looking closely it is easy to miss these details, appearing so small and insignificant in comparison to their surroundings, but this concept is crucial to the painting. These paintings display the sublimity of creation; while viewers are meant to identify with the human figures.

Riverbank

This beautiful painting vividly displays every aspect of a classic shan shui painting. There is no one focal point in this piece, the eye is drawn all over the incredible landscape. The depiction of a scholar-hermit living in elegant reclusion is something every viewer would yearn for. The wash of ink makes the mountains appear soft, and the small babbling brook on the left side and the contrasting river cutting through the mountains show the diversity of nature. This piece brings a feeling of balance while exhibiting the stunning environment.

Riverbank. By Dong Yuan (Chinese, active 930s–960s). Hanging scroll; ink and color on silk; 86 3/4 × 43 in. (220.3 × 109.2 cm). China. Southern Tang dynasty (937–76). The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

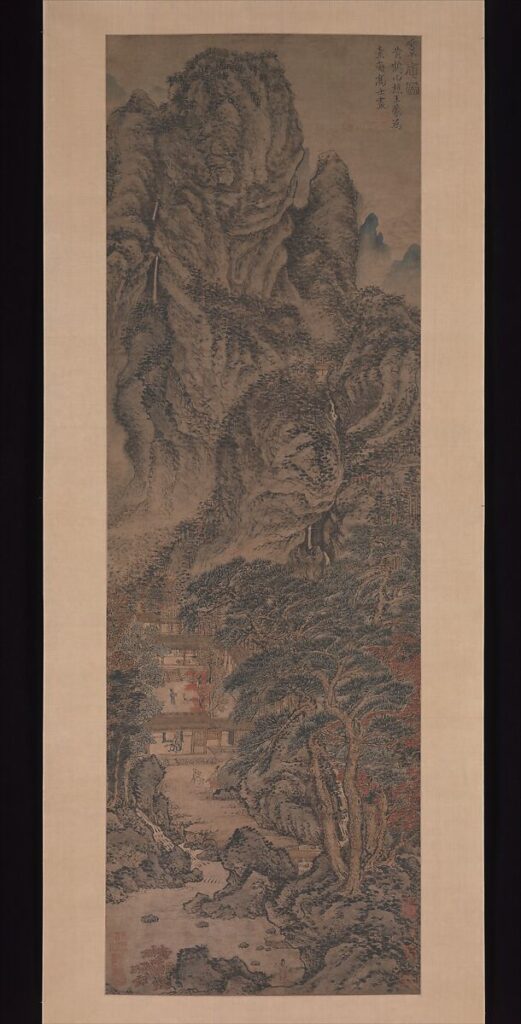

Simple Retreat

This painting centers around a retreat in a forest. The painting contains heavy Daoist imagery including deer; believed to have an incredibly long life span, attributed to the creature’s ability to locate the immortal fungus, known in Chinese as língzhī. This fungus is shown in the hands of a scholar, seated at the front gate of a rustic hermitage in the building. The crane, shown in the courtyard, also has a long-lived tradition of connection with immortality beliefs in China. The inclusion of these animals brings a whimsical, dreamlike attitude to the painting. Towering over the retreat is a strangely shaped mountain, dotted with waterfalls. Rather than jagged rock edges the mountain appears almost fluid, comprised of curved lines. This stylistic choice is odd, but it offers the landscape a sense of movement as if the mountain is alive

Simple Retreat. by Wang Meng (ca. 1308-1385). Hanging scroll; ink and color on paper; 53 3/4 × 17 5/8 in. (136.5 × 44.8 cm). China, Late Yuan (1271-1368) or early Ming (1368-1644) dynasty ca. 1370. The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

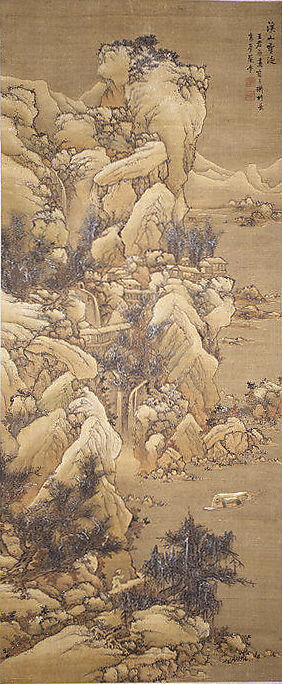

Boating amid Snowy Streams and Mountains

This painting showcases a mountain range overlooking a body of water. The scroll on which it was painted is formatted vertically with the mountain stretching from the bottom to the top. A human figure is depicted walking up the mountain at the bottom of the painting. This lone figure is reminiscent of Buddhist beliefs, following a path up to enlightenment or heaven.

Boating amid Snowy Streams and Mountains. By Lan Meng (ca. 1641-after 1671). Hanging scroll; ink and color on silk; 90 x 37 1/4 in. (228.6 x 94.6 cm). China. Ming (1368-1644) or Qing dynasty (1644-1911), mid-17th century. The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

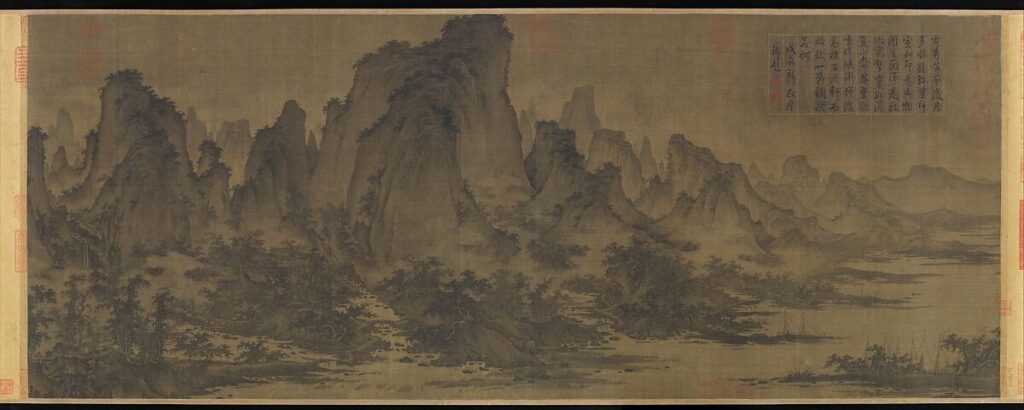

Summer Mountain

This painting, titled “Summer Mountains”, depicts a vast mountain range overshadowing a large body of water. The central mountain is truly the focal point of the painting. It reaches towards heaven, even touching the top of the silk canvas. Too large to fit into a painting, this mountain conveys the majesty of nature. The surrounding mountains, though dwarfed in comparison, span far into the background. They disappear into the mist, providing depth to the painting. The foreground of the painting includes multiple man-made structures including temples and bridges. These structures are built into the landscape, hidden behind trees and rocks. Human figures and boats are also visible, described as heading to a temple retreat. Though painted with fine detail, when observing this painting from a distance, the presence of humans is practically invisible, outshined by the lush landscape.

Summer Mountains. By Qu Ding (Chinese, active ca. 1023–ca. 1056). Handscroll; ink and color on silk; 17 7/8 × 45 3/8 in. (45.4 × 115.3 cm). China. Northern Song dynasty (960–1127)

Period: Northern Song dynasty (960–1127). The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Ten Thousand Miles Along The Yangzi River

This incredibly long scroll is difficult to take in at once, but it is formatted like this for a unique reason. The painting was made to be read like a storybook, with the viewer experiencing the trip down the river as they unroll it. When experiencing the painting in this way, the viewer passes many sights, including towering mountains, boats, and multiple pagodas. A pagoda is a very spiritual place whose original purpose was to house relics and sacred writings. They are seen on two islands adjacent to each other. The repeated depiction of this unique sacred structure stands out in this piece, they stand high on the mountains visible to all those who sail past.

Ten Thousand Miles Along The Yangzi River. By Qu Ding (Chinese, active ca. 1023–ca. 1056). Handscroll; ink and color on silk; 17 7/8 × 45 3/8 in. (45.4 × 115.3 cm). China. Northern Song dynasty (960–1127). Museum of Fine Arts Boston.

Significance

The Tang Dynasty (618 – 906 A.D.) was also known as the golden age of Chinese arts and culture. As previously conquered Chinese kingdoms began to break away, the country became divided, and its power split up among many groups. During this time of political turmoil, many men turned to art and poetry as an escape from the conflict. Retreating into the natural world, these men used ink on silk/parchment to capture the beauty of their surroundings. According to traditional Chinese beliefs, mountains are considered sacred. They are the places where the immortals reside and are very close to Heaven, both physically and spiritually. This belief is reflected very strongly in many of these paintings. Landscape paintings, often massive in size, portrayed towering mountains, waterfalls, and rivers. Water brings balance to the painting, often streams and waterfalls line the mountains, framing the peak’s beauty. Fog is also a common image in these arts, it swallows up the landscape leaving the viewer to fill in the gaps. The art of landscape painting remained popular throughout history, and skills and techniques were passed down, usually between father and son. Landscape paintings were made for reflection; the viewers of the pieces are meant to stare into the painting and find their own meaning within.

What is Asian Art?

The Chinese landscape paintings I have focused on showcase an important aspect of Asian art. It connects us, the viewer, with our spiritual beliefs and the beyond. It does not limit or push a view but allows interpretation and self-discovery. Asian art has a rich history in religious and cultural traditions, it has influenced other cultures including our own in America. While exploring the Asian art of the past and present I have learned so much about the different cultures and beliefs that are held in different areas. Many share a connection to nature and life, something I love to learn about. It is incredible to see the diversity of artistic traditions that have changed, and grown throughout time in Asia.

Reading List

Sickman, L., & Soper, A. C. (1971). Chapter 15: The Masters of Landscape. In The Art and Architecture of China. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Wong, C. K., & Chung, W. N. (1986). Classical Chinese architecture. Hongkong: Joint Pub. Co.

www.jasonpomerleau.com, J. P.-. (2016). Retrieved from https://luminous-landscape.com/the-synthesis-of-chinese-landscape-painting-and-photography/

Art, D. of A. (1AD). Retrieved from https://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/clpg/hd_clpg.htm