Abstract

This project was inspired by Yasunari Kawabata’s speech at the Nobel Prize for Literature, in which he spoke at length about Japanese esthetics with Mono no aware at its core. Having studied this concept in Japanese literature, I wanted to explore the concept of Mono no aware in Japanese painting in this project.

Momonoaware is a central concept in Japanese culture that can be translated as “the pathos of things” or “the sadness of things”, highlighting the appreciation of the beauty of fleeting things. This concept has been deeply ingrained in Japanese painting, which is characterized by its emphasis on the natural world, transience, and the emotions of the artist.

From the origins of Mononoaware, the Genji Monogatari Emaki, through the depiction of the nobility’s love of nature and the seasons during the Heian period, and their emotions when dealing with people, Mononoaware began the first steps of what would become a uniquely Japanese artistic tradition.

As the times continued to evolve, the definition of Mononoaware was adopted by the Japanese cultural scholar Motoori Norinaga in the 18th century and published in his literary commentary on the Tale of Genji, and from then on, the concept came into the public eye and subliminally influenced the development of Japanese aesthetics. It emphasizes sensitivity to things, thus often focusing on nature, the seasons, and flora and fauna, inspired by a love of the natural beauty of the changing seasons, capturing the cyclical and fleeting beauty of nature.

During the same period, the Kokugakuin movement emerged, and Motoori Norinaga, after proposing the aesthetic concept of Mono no Aware, used its uniqueness to construct a new form of Shintoism, leading to the revival of Shintoism in Japan. hence, Mono no Aware gradually became rooted in Shinto beliefs. This purely emotional response to the beauty of nature, the impermanence of life, and the sadness of death are similar to the religious attitude toward the gods: The gods are behind and within nature and one’s life and a person should revere the kami immediately, also revealed in Japanese paintings.

Later on, the introduction of Buddhism in Japan focused this belief on the transient nature of the environment and everything that exists within it. From here, the focus of Mono no aware shifted simply from awareness to a deeper appreciation of the beauty and aesthetic value of change. The overall impact of the aesthetic principle is to recognize the impermanence of everything that exists and create a deeper connection with it because of its fleeting nature.

From natural aesthetics to Shinto beliefs to the Buddhist concept of impermanence, Mono no aware has gradually taken root and permeated Japanese aesthetics, and from mere aesthetics has developed a Japanese national spirit, becoming a concept that shapes the nation’s cultural identity and reflects the essence of Japaness.

Introduction of Mono no aware

Mono no aware (物の哀れ) is a Japanese concept that can be translated as “the pathos of things” or “the sadness of things.” In early Heian times (794-1185) aware became a noun designating a profound and individual emotion that one experiences in communion with the fleeting beauty of a person, an event, a natural object, or a work of art. It refers to the bittersweet feeling of the impermanence of things and the transience of life, which is an essential aspect of Japanese culture and aesthetics.

Mono no aware is from Heian period literature and was adopted and used by the 18th-century Edo period Japanese cultural scholar Mootori Norinaga in his literary commentary on the Tale of Genji, used it to describe the emotional response one feels when witnessing the beauty and fragility of life.

The Tales of Genji provoked a kind of emotional response that was said to possess aware or mono no aware. For the courtier of the period, aware, which implied a sensitivity to the beauty and perishability of all things, was the most esteemed of all expressive qualities(Guth).

Mono no aware can be expressed in various ways, such as the beauty of cherry blossoms, the fading of autumn leaves, or the changing of the seasons. It is also present in the Japanese philosophy of wabi-sabi, which values the beauty of imperfection and impermanence. This concept has a significant influence on Japanese culture and is also present in the country’s attitude toward life and death. It encourages people to appreciate the beauty of things and to cherish the fleeting moments of life, as everything is impermanent and will eventually pass. When people have a keen sense of nature, so they follow the changing seasons to appreciate time and understand the impermanence and fragility of life. That is to say, in a world of constant movement, people see the passing and changing nature, have the feeling of beauty, but at the same time understand a warning of death, and then realize the shortness and illusion of reality.

The Genji Monogatari Emaki(Takegawa II, veranda scene)

The Tale of Genji was written between the end of the 10th century and the beginning of the 11th century. It focuses on the fate of the Genji family, especially the various women around them, and depicts the life of the aristocracy in all its elegance through the recounting of various affairs. The keen perception and delicate description of the beauty of nature, especially the changes of the seasons, and the idea of impermanence and predestination that envelops the entire book are undoubtedly the spiritual feelings of the Japanese people. Once the work was written, it was highly sought after by the high society, and people created picture books to recreate the classic scenes in the book. It is said that in the cultural salons of the imperial palace at the time, the nobles flipped through the scrolls while attendants read aloud the contents of the stories, and later developed a form of combining a book of words with a painting, in which passages of text were interspersed between each painting to explain the plot shown in the picture. At the end of the Heian period, this form of expression became the unique art of the scrolls in the history of Japanese painting.

The creators of the Genji Monogatari Emaki often used the Hikime kagibana technique to depict the silhouette of the characters, with only thick eyebrows, linear eyes, hooked noses, and red lips. Both male and female characters are depicted with the outer corners of the eyes turned upwards, similar to “Danfeng eyes”, without pupils, and with a long, thin, hooked nose that resembles the Japanese kana character “く”. This technique is usually used only for characters of high status, to show the gravity and elegance of those in high positions, and to distinguish the status of the characters. The two noble women depicted in this illustration for the chapter Takegawa II are drawn using the Hikime Kagibana technique.

Another technique used to depict interior architecture is called Fukinuki yatai, in which the roof is not painted, and a top-down oblique view is used to present a view of both the inside and outside of the house. It was on the wide verandas linking indoors and outdoors that much of the aristocratic appreciation of seasonal change took place, as in this springtime scene of court ladies viewing a flowering cheery tree. shows the appreciation of the subtle changing of the seasons, and it was in the world of the Heian court that such appreciation reached unique levels of refinement.

In the corner, there are people who admire the two women peeping in through the slit of the bamboo curtain, and the cherry blossoms surrounding them are scattered and fallen by the wind. In this scene, “beauty” and “sorrow”, youth and fading are intertwined at the moment, which arouses the audience’s deep and keen empathy, and they feel a tragic love story between the falling cherry blossoms that may be caused by the difference of class.

Pine Trees

This painting is an example of the art of ink painting. The world here does not look like what people actually see. In its place are quick, rough lines and silent variations of black and gray, even empty spaces, depicting the essence of the forest. The person viewing a painting must have a keen eye for natural forms. For he will find not only the physical objects in the painting in his emotions and imagination, but also the unique features of the painting one-by-one its moods, its seasons, and the way it shows the cosmic process to another generation of beings(Picken, 58). It depicts a pine forest shrouded in mist, with faint snow-capped mountains in the distance, and the foreground trees are composed of short, thick, dry brushstrokes. It creates a black outline with clear forms and suggests its visual proximity to the viewer, hence its location in the foreground. The pine trees in the back consist of long, pale, wet brush strokes. These trees are virtually shapeless through their soft contours and minimal detail, thus suggesting their visual distance from the viewer. Furthermore, the painting’s composition also contributes to a sense of mono no aware. The trees are positioned and spaced in such a way that they convey a sense of depth and perspective, drawing the viewer’s gaze into the painting and emphasizing the vastness of the natural world. It reflects the respect for nature and allows the viewer to feel the smallness of life under the vastness of nature, thus having a more delicate Mono no aware feeling.

Wind God and Thunder God(風神雷神図)

One of the examples of Japanese painting that embodies the concept of Mono no aware is the “Wind God and Thunder God” screen by Tawaraya Sotatsu in the early 17th century. The painting is part of a pair of folding screens and depicts two powerful and dynamic deities, Raijin (the god of thunder) and Fujin (the god of wind) in Shinto religion. The Wind God that controls the wind, and the Thunder God that controls thunder both have continental roots and appear in Japan’s oldest documents, namely, the “Kojiki” (Records of Ancient Matters) and “Nihonshoki” (Chronicles of Japan).

To analyze this painting, It is necessary to mention Mootori Norinaga, who developed the concept of Mono no aware, protested against the rationalistic tendencies in the analysis of Neo-Confucianism and Buddhism coming from China, based on his analysis of Kojiki, the oldest document in Japan, during the Kokugakuin movement that was started in the 18th century. He argued that this rationalistic approach to heaven and earth and their origins were intended to foster a mood of indifference to the irrational, to the transcendent and mysterious beyond human beings (Picken, 60). His reading of Kojiki is that the native Way of Japan was a Way created not by humans like the imported Chinese Ways, but by the native god who is ultimately responsible for all human action and activity (Fujiwara). Thus, god is central to Norinaga’s idea of the native Japanese way, and one way to stimulate this transcendent and absolute nature perceived through myth is to cultivate Mono no aware, thus creating reverence for nature and for the deity behind it. He uses this analysis to construct a new form of Shintoism.

In this painting, the gods of wind and thunder appear to be floating in the air, thanks to Satatsu’s use of a dark cloud drawing technique. The dark clouds riding at the feet of the gods of wind and thunder were created by mixing ink with silver paint to give the ink a lighter tone, thus creating an uneven sheen and a floating appearance. The composition with the god of wind on the far left and the god of thunder on the far right and the golden background create the implication of an endless expanse of space. The viewer can feel the power of the gods and the vastness of the universe in it, which is how Mono no aware is applied under Shinto’s beliefs.

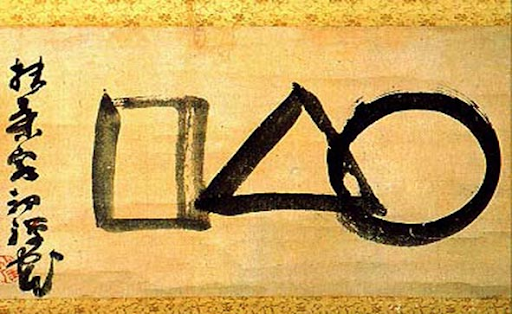

○△□(The Circle, Triangle, Square)

After Buddhism was introduced to Japan, it was gradually combined with the original Japanese Shinto religion to become Japanese Zen. Shintoism aims to cultivate personal awareness of one’s surroundings and deities and emphasizes openness and sensitivity to the energies that exist in the world. zen, on the other hand, focuses this belief on the transient nature of the environment and all that exists within it. Understanding and accepting the innate uncertainty of life, highlighting our ability to enjoy life by appreciating its fleeting moments. The unavoidable nature of finite existence is contrasted with the never-ending stream of change, as life continues to occur despite the continuous passing of objects and experience. The realization of impermanence is therefore bittersweet, tinged with mourning, and yet also capable of recognizing the beauty of change in itself.

The circle represents infinity, and infinity is the basis of all life, but infinity itself is formless, and the triangle is the beginning of all forms, and the square is the doubling of the triangle, and this doubling process goes on infinitely, and we have the diversity of things, and on this basis, all kinds of things form and change infinitely, thus constituting this universe. This impermanence of all things in the world is the core concept of Japanese Zen under the influence of Shinto, and to experience this impermanence and thus feel the sadness of the passing of life is a further expansion of Mono no aware.

The Great Wave(神奈川沖浪裏)

Created at a time when Japan was in closed country, this woodblock print depicts three fishing boats about to be swallowed by a giant wave beneath magnificent waves, while Mount Fuji, representing the land of Japan, is out of reach. Hokusai employs a low-horizon composition with giant waves occupying two-thirds of the frame, giving the image a dynamic element through its giant movements. At the same time, he uses depth perspective to make the center of the picture, the highest point in Japan, Mount Fuji, appear as a small triangular mound within the hollow of the cresting wave, which reaches out to the three fishing boats tossing in the waves and Mount Fuji in the distance like an evil claw, overshadowing the whole picture with fear and anxiety. The painting is a reflection of turbulent Japan with its fear and anxiety, fearing that the sea, which has always protected its peaceful isolation, will lead to Japan’s decline, hinting at its uneasy future. The fishermen’s struggle under natural disasters and the static Mount Fuji in the distance also represent the unwavering spirit of Japan itself. The visual impact of this confrontation between human beings and nature embodies the beauty of a tragic and overwhelming moment, where Mono no aware shows a choice to “live to die”, that is, that human beings are just a drop in the ocean between heaven and earth. In the face of such a powerful force of nature, the struggle of human beings is the beauty of national spirit and moral integrity born from Mono no aware.

Japaness

Using the same woodblock print The Great Wave as an example, we can clearly see how Mono no aware has gradually penetrated Japanese aesthetics and culture over time and has become closely associated with the concept of “Japaness”. The Great Wave is not only a depiction of natural scenery and a sense of space but also has the sad beauty of the passing of life that Shinto and Japanese Zen revere. The fishermen’s struggle with nature in this painting belongs to that, as this “beauty” is likely to perish after its fragile existence. This fragile and passing nature also makes people sensitive to the vulnerability of “beauty”; and the sense of beauty fading also makes the “beauty” in the spiritual world accompanied by “sorrow”. This sense of Mono no aware transcends time and religion and remains deeply in the Japanese nationality and spirit.

Bibliography

12th century. scroll titled Genji Monogatari. Place: Goto Bijutsu-kan Museum, Tokyo, Japan. https://library.artstor.org/asset/HUNT_58900.

Tawaraya Sotatsu. 17th century. Wind God and Thunder God. Tokyo National Museum, Tokyo, Japan. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Wind-God-Fujin-and-Thunder-God-Raijin-by-Tawaraya-Sotatsu.png

Hasegawa Tohaku, 1539-1610. Pine Wood: det.: of screen. https://library.artstor.org/asset/ARTSTOR_103_41822000413177.

Sengai Gibon. 1819-1828. The Circle, Triangle, Square. https://terebess.hu/zen/sengai.html

Artist: Katsushika Hokusai (Japanese, Tokyo (Edo) 1760-1849 Tokyo (Edo)). ca. 1830-32. 「富嶽三十六景 神奈川沖浪裏」 / Under the Wave off Kanagawa (Kanagawa oki nami ura), or The Great Wave, from the series Thirty-six Views of Mount Fuji (Fugaku sanjūrokkei). Woodblock print, Prints. Place: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, https://www.metmuseum.org/. https://library.artstor.org/asset/SS7731421_7731421_11748794.

Guth, Christine M. E. “Japan: Connoisseurship and historiography.” Grove Art Online. 2003; Accessed 12 May. 2023. https://www.oxfordartonline.com/groveart/view/10.1093/gao/9781884446054.001.0001/oao-9781884446054-e-90000369708.

Prusinski, Lauren. “Wabi-Sabi, Mono no Aware, and Ma: Tracing Traditional Japanese Aesthetics through Japanese History.” Studies on Asia Series IV, 2, no. 1 (03, 2012): 25-49. https://login.peach.conncoll.edu/login?url=https://www.proquest.com/scholarly-journals/wabi-sabi-mono-no-aware-ma-tracing-traditional/docview/1095107832/se-2.

Kato, Kazumitsu. “Some Notes on Mono No Aware.” Journal of the American Oriental Society 82, no. 4 (1962): 558–59. https://doi.org/10.2307/597529.

Picken, Stuart D. B., and Edwin O. Reischauer. Shinto : Japan’s Spiritual Roots. First edition. Tokyo ;: Kodansha International Ltd., 1980.

Lippit, Yukio, James T. Ulak, Keiko Nakamachi, Shunroku Okudaira, Ryō Furuta, Takeshi Noguchi, Aya Ōta, and Sōtatsu Tawaraya. Sōtatsu. Washington, DC: Arthur M. Sackler Gallery, Smithsonian Institution, 2015.

Fujiwara, Gideon and Peter Nosco, “The Kokugaku (Native Japan Studies) School”, The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Fall 2021 Edition), Edward N. Zalta (ed.), URL = <https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/fall2021/entries/kokugaku-school/>.