Overview:

Gender expression in artwork is oftentimes a complicated issue to explore because of the many expectations, stigmas, and stereotypes surrounding it. Women in every society are expected to act and dress in ways that show their courtliness and readiness to marry, whereas men are expected to be the protectors of their houses and societies, reflecting values of toughness and valor. These subjects even become more complicated when the standards of every worldly region are considered. And thus, art has been used throughout the centuries to portray these very real aspects of human society, showing the good, bad, and neutral aspects of how men and women act and are treated in their respective cultures.

However, one aspect of gender expression is not often explored: Androgyny, which means displaying both feminine and masculine characteristics in the ways someone dresses and acts. Though androgyny, as well as gender fluidity, has been around for centuries, there is a lot of stigma around gender expressions that do not confine themselves to the binary. Though modern day society still struggles with accepting this form of expression, there is newfound acceptance of people who choose to express themselves that way, making discussions around them more widespread. When looking into more modern day Japanese artwork and media, there are examples of androgyny, so in the process of developing my topic, I wondered whether there were older artworks displaying different kinds of androgynous gender expression.

This exhibition shows many different examples of gender expressions falling outside the more acceptable binary throughout Japanese history, as well as the movements and social standards at the time that made them acceptable. This includes two Jomon Period clay figurines, two Edo Period woodblock prints, and a more modern example shown in a Studio Ghibli film. Some of the textual evidence used to analyze these artworks were The Disappearance of Japan’s “Third Gender” and A Labyrinth of Gender In Kabuki Theater. The first text introduced the Edo period concept of the Wakashu, who are “male youths transitioning between being a child and an adult” and often adopt the looks of young, unmarried women with their long topknots and beautifully detailed kimonos. The second text also focused on the Edo period and talked about the varying gender expressions seen in kabuki theater. Because women were not allowed to act in Kabuki theater due to existing gender discrimination, men called Onnagata arose who specialized in performing as women. These books provide a more hidden history of androgynous gender expression in historical Japan most likely left out by regular history books, which helped provide this exhibit with an even deeper context about this subject. In addition, though many regions worldwide have different ways of expressing gender outside the binary, by reading these books and studying these artworks, I am able to analyze why these examples are specific to the Japanese experience. This exhibition also explores who was allowed to dress and act in a more androgynous way, why that might be, and how existing gender roles and expectations play into this culture of gender fluidity throughout Japan’s history.

Dogū (Clay Figurine):

Creator: N/A

Period: Final Jomon Period (ca. 1000-300 BCE)

Culture: Japan

Medium: Earthenware with cord-marked and incised decoration

Dimensions: H. 6 1/8 in. (15.6 cm); W. 7 1/4 in. (18.4 cm); D. 2 3/4 in. (7 cm)

Repository: The MET

This Jomon period figurine is an excellent example of androgyny found in ancient Japanese culture and were often thought to have been used for healing and fertility issues, where they would be broken at the waist during the procedure. This is why many figurines from this period are only found with the top half of their body. These ceramic sculptures have a variety of descriptors and proportions that delve into both the feminine and masculine, giving it a more gender fluid feeling. This piece was given breasts, which are very feminine, but the torso of a man, which is often portrayed as being quite wide at the shoulders and much narrower at the hips. In addition, the figure has short hair, which can be seen as very androgynous, but has larger lips, which are often seen in descriptions of women. Lastly, this figure may be wearing jewelry, seen with the band around their neck, which is also a non-gendered decoration for many cultures around the world. However, figurines at the time may have been more inclined to display gender-neutral descriptors because of the frequent blending with animals in artwork, which not only blurs the line between female and male, but also between human and animal.

Bust of a Figurine:

Creator: N/A

Period: Final Jomon Period (ca. 1000-300 BCE) or later

Culture: Japan

Medium: Stone

Dimensions: H. 3 1/4 in. (8.3 cm); W. 2 in. (5.1 cm); D. 2 1/4 in. (5.7 cm)

Repository: The MET

This piece also belongs to the Final Jomon period, which was the first period in Japanese history, but there are some differentiating features. This piece was carved of stone and does not have as many intricate details as the first Jomon Period figurine, however, it still displays gender fluid characteristics. Though only the chest and head are left of this piece, it still has breasts, which are a very feminine characteristic, as well as a wide, barrel-like chest often displayed in masculine figures. This piece also has a ring around its neck reminiscent of jewelry and short hair similar to the other piece. This bust is very similar to that of the “Venus” figures found in Europe, however this one differentiates because of their more masculine features, giving it a more androgynous feel. Because of these descriptors, this piece acts as another excellent example of an androgynous culture in ancient Japanese culture.

Young Man (Wakashu) with a Miniature Flower Cart:

Creator: Ishikawa Toyonobu (Japanese, 1711–1785)

Period: Edo period (1615–1868)

Culture: Japan

Medium: Woodblock print; ink and color on paper

Dimensions: H. 14 1/4 in. (36.2 cm); W. 6 in. (15.2 cm)

Repository: The MET

This piece displays a certain androgynous fashion acceptable during the Japanese Edo Period: the Wakashu. Wakashu were “male youths transitioning between being a child and an adult” (Bohnke) who were often seen wearing their hair in a very feminine topknot not unlike that of a woman’s hairdo, except for the small triangle they shaved at the crown of their hair. They also wore very colorful and beautifully decorated kimonos like those of unmarried women. Women could also partake in the Wakashu culture, though it was quite looked down upon. Once these male youths were ready to become adult men, they would partake in the Genpuku and start sporting masculine haircuts and clothing. However, it was also acceptable for these male youths to continue to be Wakashu for the rest of their lives. This piece shows the acceptability for men (not women though, which is important to note) in a more modern era to dress in a very gender non-conforming way, unlike many of the other countries around the world who set very strict standards for the two genders.

The Actor Arashi Tokusaburō as the Female Gallant (Onnadate) Ohashi:

Creator: Utagawa Sadamasu (Kunimasu)(Japanese, active ca. 1830–1852)

Period: Edo period (1615–1868)

Date: 1838

Culture: Japan

Medium: Woodblock print (nishiki-e); ink and color on paper; vertical ōban

Dimensions: 14 3/4 × 9 5/8 in. (37.5 × 24.4 cm)

Repository: The MET

This piece shows the renowned Kabuki actor Arashi Tokusaburō III, who was an onnagata, meaning he specialized in acting as women. Kabuki theater restricted access to women actors, however women characters still needed to be present for the plays to be complete, so onnagata specialized in playing women in these performances. To do so, these men wore feminine makeup, beautiful kimonos, and intricate hairstyles, as seen on Arashi, in order to give these fantastic performances, and were greatly revered for doing so. This piece shows the gender fluidity allowed in Japan, and the great acceptance for such, however, it also shows the limitations to this gender expression. Women were often not allowed to partake in these plays and were still greatly restricted by the patriarchy, thus leading to the creation of the onnagata.

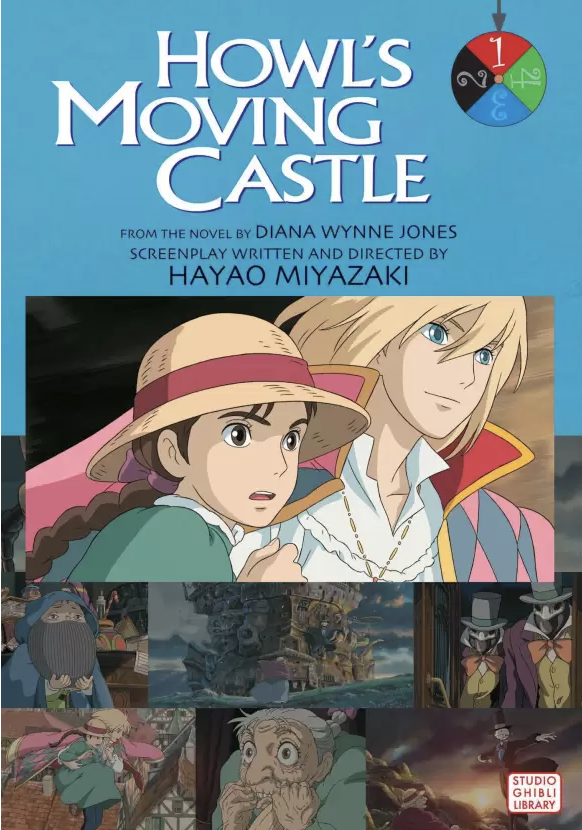

Howl’s Moving Castle (Hayao Miyazaki):

Creator: Hayao Miyazaki (Studio Ghibli)

Date: June 17th, 2005

Culture: Japan

Medium: Film

The character designs in Howl’s Moving Castle, whether intentionally or unintentionally, display aspects of androgyny for many of the characters. When looking at the faces of the two main characters, Sophie and Howl, their faces are almost exactly the same. However, as the characters age, their features become much more gendered, as seen with the version of older Sophie, as well as with Madame Sulliman. This characteristic brings in the idea of infantilization of both younger feminine and masculine characters, which is also often seen in other anime such as Demon Slayer and Hunter X Hunter. It is much more acceptable for younger people to be more fluid with their gender expression, which can also be seen with the Wakashu, however, as someone gets older, the gender binaries of female and male are more strictly enforced. This is a necessary concept to understand when analyzing when, where, and for whom androgyny is acceptable in both historical and modern Japan.

Works Cited:

“Dogū (Clay Figurine): Japan: Final Jōmon Period (ca. 1000–300 BCE).” The Metropolitan Museum of Art, www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/44824. Accessed 8 Dec. 2023.

Isaka, Maki. Onnagata: A Labyrinth of Gendering in Kabuki Theater. University of Washington Press, 2016. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctvcwnjxz. Accessed 6 Dec. 2023.

Japanese, Ishikawa Toyonobu. “Ishikawa Toyonobu: Young Man (Wakashu) with a Miniature Flower Cart: Japan: Edo Period (1615–1868).” The Metropolitan Museum of Art, www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/55776. Accessed 8 Dec. 2023.

Bohnke, Christin. “The Disappearance of Japan’s ‘Third Gender’ – JSTOR Daily.” JSTOR Daily, 22 Dec. 2021, daily.jstor.org/the-disappearance-of-japans-third-gender/.

Utagawa Sadamasu (Kunimasu) 初代歌貞升 Japanese. “Utagawa Sadamasu (Kunimasu) 初代歌貞升: The Actor Arashi Tokusaburō as the Female Gallant (Onnadate) Ohashi: Japan: Edo Period (1615–1868).” The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1 Jan. 1970, www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/843993.

“Bust of Figurine: Japan: Final Jōmon Period (ca. 1000–300 BCE) or Later.” The Metropolitan Museum of Art, www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/62384. Accessed 8 Dec. 2023.

Santi, Blaise. “The Ending of Howl’s Moving Castle Explained.” Looper, Looper, 24 July 2023, www.looper.com/1345713/howls-moving-castle-ending-explained/.

Japanese, Katsukawa Shunshō 勝川春章. “Katsukawa Shunshō 勝川春章: The Actor Segawa Kikunojō III as Wappa No Kikuō in a Woman’s ‘Asahina Armor Pulling’ (Asahina No Kusazuri-Biki) Scene: Japan: Edo Period (1615–1868).” The Metropolitan Museum of Art, www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/56966. Accessed 17 Dec. 2023.