Introduction

In the aftermath of the Second World War, Japan was faced with the daunting task of rebuilding its nation across all perimeters– physical, economic, social and political. Following the brutality of the carpet bombings that obliterated Tokyo, a new architectural movement emerged from the ashes of the metropolis– Metabolism. During the 1960s, a small group of young architects under the guidance of their mentor, Tange Kenzō, saw ample opportunity in many of the spaces that had opened up, particularly in the skyline. Despite the movement’s cultural moment having since long passed, the presence of its influence on the design of urban landscapes both in our shared reality, as well as the ones we create in visual media is undeniable. Following the end of Metabolism’s reign, which had introduced Japan to a new wave of futuristic and technologically advanced architecture, the economic landscape of Japan was approaching the peak of its corporate bubble economy; the 1980s proved to be the decade in which Japan began to present itself as an economic powerhouse capable of competing with Western nations (i.e the United States). Japanese video games, home electronics, fuel-efficient cars and even animated media saw their worldwide breakout during this era; while the people of Japan found themselves caught up in the tides of excitement, hope and even skepticism towards their domestic market flourishing in the face of this abrupt financial success, the narrative pushed by Western economists and media creatives was very dramatically different.

Coinciding with this sudden “bubble economy” was the emergence of a new subgenre of science fiction: cyberpunk. While still incredibly popular in today’s sci-fi media (see Cyberpunk 2077, Black Mirror, Ready Player One, e.t.c), cyberpunk traces its roots back to the start of the 1980s as filmmakers, artists and authors across the globe began speculating about how this epoch of time would shape humanity’s future. The 1982 release of Ridley Scott’s feature length film, Blade Runner is often credited as being the first ever film within the subgenre, and in the same year, Otomo Katsuhiro began releasing his serialized manga, Akira. This manga was later accompanied by the release of an animated film of Akira in 1988, 2 years before the manga that the film was based upon came to an end. While both franchises fall under the same niche of science fiction and display a myriad of similarities in visual design to display a dark, dystopian future, the influences that birthed such media are dramatically divided on a cultural level. Over the course of this essay, the ideological disparities between the influences that shaped these two beloved pieces of cyberpunk media will be explored, and the concept of “Japan-ness” as it is portrayed in Western media will be deconstructed and compared to media that is “innately Japanese”.

Akira & Metabolism

Otomo Katsuhiro was born in 1954 in Miyagi Prefecture, Japan, and grew up in the midst of the concentrated efforts to rebuild the country in the aftermath of the Allied Powers’ defeat of Imperial Japan. Having witnessed the coinciding newfound successes of both the Metabolist movement and domestic tech industries, alongside learning of the near total destruction of the world around him that he narrowly avoided by a decade, Otomo began constructing his bleak vision of Tokyo’s 21st Century destiny. Akira is set in the year 2019, taking place in Neo Tokyo– yet another iteration of the capital city following its atomic-scale obliteration in the year 1988. Likewise to Metabolist architecture dominating the subsequent decades of the Second World War, yet another updated style of buildings and urban planning formed the fascist state that the gang of delinquent bikers would be forced to navigate and ultimately, attempt to survive in. With megastructures clustered together in suffocating proximity and highways weaving between skyscrapers several hundred meters in the air, one cannot help but wonder as to where Otomo sourced his inspiration for such a domineering urban landscape. As briefly outlined in the scope of this publication, the Metabolism movement was a revolutionary approach to Japanese urban planning and architecture, with its core design principles evidently applied to the new-millenium-nightmare of Neo Tokyo. Metabolism sought to completely restructure the way the nation understood urbanism. By reconsidering cities as not just a collection of buildings and roads with people inside, but instead, a complex living organism with a diverse set of smaller working parts that interact with one another to form the city, the ways new buildings are implemented into cities becomes more flexible and organic. Buildings such as Kurokawa Kisho’s Nakagin Capsule Tower, as well as Isozaki Arata’s proposal for his “City in the Air’ were comprised of smaller separate subunits that intuitively fit together until they took the form of the one complete structure– not unlike the numerous cells that make up the tissues and organs of one singular organism. In a 2023 article for Museé Magazine, Winjie Zhao further explained the intentions behind Isozaki’s vision of cellular megastructures citing the Metabolist Manifesto: “By incorporating elements of space, speed, and drastic change in the physical environment, we created a method of structuring having elasticity and changeability.” The strategic layering of these idyllic cities ultimately paved the way for the urban design of Neo Tokyo, with a more dystopian twist. Instead of the stratified city fostering a haven of community and sustainability, it instead throws the audience into a nightmarish arena of towers large enough to block out the sky and separate humans from nature.

https://i.pinimg.com/originals/57/ed/7b/57ed7bb492e310f9a53fc89f76eeca47.jpg

Otomo Katsuhiro, Akira, 1988, Animated Film, TMS Entertainment

This screencap depicts the skyline of downtown Neo Tokyo from the ground level. Moving from the foreground through to the middleground and background, there are a number of high-rise buildings that increase in size moving further away from the initial point of view, until the outer-perimeters of what would be the sky are completely dominated by even more of the city’s megastructures. By intentionally overwhelming the field of view with a plethora of these skyscrapers, a sense of personal insignificance and overstimulation is provoked within the audience, generating the impression that the world the characters of Akira exist in is dystopian, and entirely overrun by technology. Moreover, the night time setting of this scene further emphasizes the extent to which advanced technology has become so integral to this futuristic society with the complex layering of artificial lighting in the form of neon colors lining the edges of buildings, alongside the high beams waving through the sky.

https://i.pinimg.com/originals/75/bd/04/75bd04a0a9e5ffc49ba45dfb95235965.jpg

Otomo Katsuhiro, Akira, 1982-1990, Ink on paper, Manga, Kodansha

In these two panels from a page of the Akira manga, more of Neo Tokyo’s immense architecture is yet again portrayed from the ground level, from the perspective of an individual on a motorbike following behind two other people, also on motorbikes. Likewise to the previous image, presenting the architecture of the city from the perspective of a single person allows for the audience to gain a more succinct understanding of how the physical environment of Neo Tokyo is felt by the residents. The wide road which continues straight through the blocks of densely packed buildings appears entirely hostile to pedestrians, being dominated by vehicles; the inaccessibility of the city to those who want to travel without any mechanized technology conveys a sense of isolation and minimal social interaction due to the lack of facilities for the typical interpersonal interactions that would otherwise occur in a more pedestrian-accessible environment.

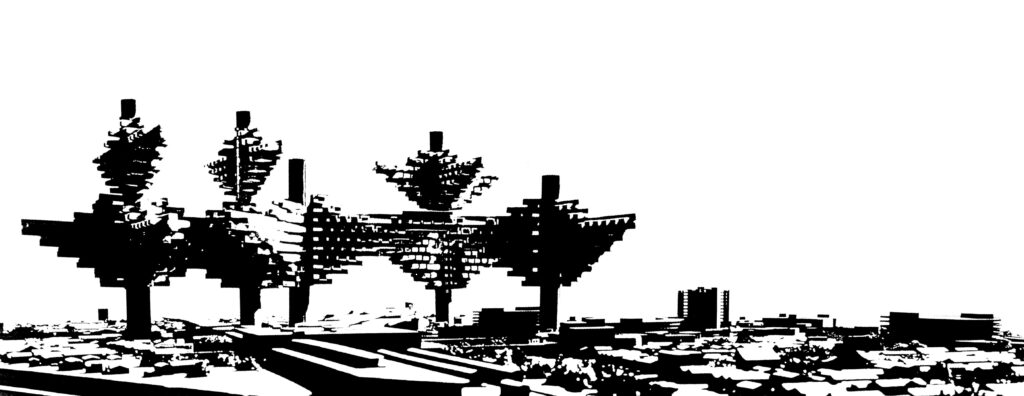

This screen print of Isozaki’s rendition of “City in the Air” displays the architect’s vision for Tokyo in the near future. The large tree-like structures that dominate the left side of the image overlook the older, lower height buildings that comprise the more “traditional” city. The tree-like structures were designed to be constructed out of a number of singular, interchangeable units that would accommodate commercial, residential and business properties, that could be built and expanded upon according to the needs of the growing city’s population, which were anticipated to change in future generations. This multi-level approach to urban living was one of the core aspects to Metabolist design that allowed cities to be treated as complex, multicellular organisms.

Blade Runner & Techno-orientalism

Conversely, Ridley Scott’s foreboding vision of Los Angeles has all of the essential elements of a cyberpunk city that Akira does. Colossal towers lined with neon lights, buildings tall enough to blot out sunlight and a bustling metropolis of millions of people struggling to survive in the face of corrupt governments and conglomerates. Yet the question begs, “Why did this iconic American city become so Japanese?” Techno-orientalism is a trope unique to sci-fi media which portrays East Asian people and society as having become so technologically advanced that they have lost their sense of humanity. The implementation of such a trope throughout sci-fi media stems from the “Japan-panic” experienced by the United States in the 1980s. Poet-critic Eleonor Botman published a scholarly article arguing that Japan’s bubble economy of the 1980s was essential in the shaping of Akira’s universe, noting “Following World War II, Japan dominated the electronics industry…The nation’s GDP, by the 80’s, surpassed many developed Western countries.” Botman’s attention to Japan surpassing developed Western nations along a measurable axis is crucial to the idea that both Otomo and Scott’s works are reflective of the same global socio-economic phenomenon from vastly different perspectives. Throughout Scott’s feature length film, an array of motifs conveying a sense of “Japan-ness”. Unlike Otomo’s dystopia, which is innately Japanese (being set in Japan, all characters being Japanese and Otomo himself being affected by the events of growing up in Japan in the mid 20th Century), the British director of Blade Runner was merely emulating the concept of Japanese culture through the use of visuals to convey particular ideas to Western audiences. It can be argued that in witnessing the rise of Japan as a global tech giant, Scott’s vision of the United States would become a landscape rife with Japanese soft influence (through the implementation of cultural relics such as music, consumer products, etc), and in order to communicate Japan’s presence in this dystopian world, “Japan-ness” was successfully executed. Unlike the aforementioned innate “Japanese” qualities that denote the world of Akira as being truly Japanese, Scott, whether consciously or not, has reiterated a trope that has existed since Western Europe began trading “art” with Japan. In the Isozaki’s essay “Japan-ness in Architecture”, the pioneering architect makes a commentary on how the West has created an idea of Japan that is entirely separate from Japanese culture itself, and is instead the product of an orientalist-motivated fetishization of Japanese culture, satisfying the tastes of exoticists who sought out Japanese pieces for collection. However, likewise to how the Japan-ness conveyed in the aesthetics of Blade Runner are not a representation of authentic Japanese culture, the pieces sought out by Westerners from Japan were not considered real art, nor the creators considered real artists. Therefore, it can be argued that the Japan-ness of Blade Runner exists not as the outcome of unique lived experiences like the Japanese qualities of Akira, but rather to captivate Western audiences with their already present fears of Japan, and manifesting them into an cultural-existential crisis in film format.

Ridley Scott, Blade Runner, 1982, Feature length film

In this screencap of Scott’s 1982 film Blade Runner, a small section of Los Angeles’ skyline can be seen from the air, several hundred meters above ground level. Like many shots within Akira, the city in Blade Runner is often seen under the cover of night, with much of the buildings shrouded in darkness except for the artificial lighting coming from the insides of the skyscrapers. One of the most prominent features of this screencap is the painted face of a geisha that covers the entirety of a skyscraper’s face, which adds an ominous atmosphere to her presence given that she is surrounded by darkness and a lack of visible human presence. Considering the socio-economic context of techno-orientalism, and the West’s fear of Japanese dominance in the coming decades, the racially motivated presentation of Japanese people having the greatest cultural influence in a dystopian society becomes increasingly apparent, instilling or potentially reinforcing the notion that Japan is an apparent threat to the cultural identity and economic agency of the United States.

https://www.cageyfilms.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/11/blade-runner_05.jpg

Ridley Scott, Blade Runner, 1982, Feature length film

Here, the audience is introduced to Scott’s vision of Los Angeles from a more intimate perspective. This scene is set on the narrow walkways of a night market, where the camera pans to an Izakaya operated by two Japanese men, with customers of Japanese descent wearing Japanese-inspired clothing (e.g the woman in the conical hat) occupying the seating area. A sense of claustrophobia is created through a combination of low ceilings, slender pathways and an apparent lack of natural lighting, as well as the foreground of the shot being cluttered with miscellaneous objects.

Conclusion

In summary, Akira and Blade Runner have both been astoundingly influential pieces of cyberpunk media at the conception of the subgenre. Despite having laid the foundations for the genre-defining aesthetics of cyberpunk, these works hail from two different realities. Understanding and discerning the distinctions between a piece of media that is truly Japanese versus an inauthentic portrayal of Japanese culture has much broader implications in an increasingly globalized world with a growing number of cultural exchanges– the importance of such a skill becomes even more apparent when the creation of inauthentic Japan-ness stems from racialized fears and nationalist attitudes.

Bibliography:

- Betsy Huang, David S. Roh, Greta A. Niu, Techno-Orientalism, 2015

- Lok Siu and Claire Chun, Yellow Peril and Techno-orientalism in the Time of Covid-19: Racialized Contagion, Scientific Espionage, and Techno-Economic Warfare, 2020

- Eleonor Botman, Mutated Megastructures: The Architecture of Akira, 2017

- Isozaki Arata, Japan-ness in Architecture, 2003

- Wenjie Zhao, Architecture: City in the Air, 2023